Infrastructure and PHC Services in Nigeria: the Case of Delta State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year 2019 Budget

DELTA STATE Approved YEAR 2019 BUDGET. PUBLISHED BY: MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING TABLE OF CONTENT. Summary of Approved 2019 Budget. 1 - 22 Details of Approved Revenue Estimates 24 - 28 Details of Approved Personnel Estimates 30 - 36 Details of Approved Overhead Estimates 38 - 59 Details of Approved Capital Estimates 61 - 120 Delta State Government 2019 Approved Budget Summary Item 2019 Approved Budget 2018 Original Budget Opening Balance Recurrent Revenue 304,356,290,990 260,184,579,341 Statutory Allocation 217,894,748,193 178,056,627,329 Net Derivation 0 0 VAT 13,051,179,721 10,767,532,297 Internal Revenue 73,410,363,076 71,360,419,715 Other Federation Account 0 0 Recurrent Expenditure 157,096,029,253 147,273,989,901 Personnel 66,165,356,710 71,560,921,910 Social Benefits 11,608,000,000 5,008,000,000 Overheads/CRF 79,322,672,543 70,705,067,991 Transfer to Capital Account 147,260,261,737 112,910,589,440 Capital Receipts 86,022,380,188 48,703,979,556 Grants 0 0 Loans 86,022,380,188 48,703,979,556 Other Capital Receipts 0 0 Capital Expenditure 233,282,641,925 161,614,568,997 Total Revenue (including OB) 390,378,671,178 308,888,558,898 Total Expenditure 390,378,671,178 308,888,558,898 Surplus / Deficit 0 0 1 Delta State Government 2019 Approved Budget - Revenue by Economic Classification 2019 Approved 2018 Original CODE ECONOMIC Budget Budget 10000000 Revenue 390,378,671,178 308,888,558,897 Government Share of Federation Accounts (FAAC) 11000000 230,945,927,914 188,824,159,626 Government Share Of FAAC 11010000 230,945,927,914 188,824,159,626 -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Famers' Socio-Economic Characteristics, Cost and Return of Catfish Farming in Delta North Agricultural Zone of Delta State, Ni

International Journal of Innovative Food, Nutrition & Sustainable Agriculture 8(3):43-50, July-Sept., 2020 © SEAHI PUBLICATIONS, 2020 www.seahipaj.org ISSN: 2467-8481 Famers’ Socio-Economic Characteristics, Cost and Return of Catfish Farming in Delta North Agricultural Zone of Delta State, Nigeria *Oyibo, Amaechi, A., Okechukwu, Frances. O & Onwudiwe, Elizabeth O Department of Agricultural Education Federal College of Education (Tech), Asaba, Nigeria *Corresponding Author: [email protected]; 0815592500 ABSTRACT This study was carried out to famers’ socio-economic characteristics, cost and return of catfish farming in Delta North Agricultural Zone of Delta State, Nigeria. Specifically, the study described the socioeconomics characteristics of catfish farmers and determined the cost structure and returns of catfish farming. A multistage sampling procedure was used to select 240 catfish farmers. Primary data were used for the study. Data were collected using structured questionnaire. Descriptive statistics and gross margin analysis were used to achieve the objectives while ANOVA was used to test the hypothesis. The result of the study revealed that 75.84% of the fish farmers were males while females constituted 24.16%. Total cost, total revenue, mean gross margin and mean net profit realized from catfish production in the study area were ₦2,505,128.58, ₦2,670,133.33, ₦725,213.08 and ₦165,004.75 respectively. The return on investment (ROI) for the study area was N1.07: N1. The study concluded that catfish farming was profitable in the study area. The study recommended among others that the farmers should be trained on how to formulate their own feed especially with cheaper feed components to reduce the cost of feed in catfish farming operations Keywords: catfish farming, technical efficiency, , cost and returns INTRODUCTION In Africa, the governments of the continent under the tutelage of the African Union, have identified the great potential of fish farming and are determined to encourage private sector investment (NEPAD, 2005). -

Perception of Adolescents on the Attitudes of Providers on Their Access and Use of Reproductive Health Services in Delta State, Nigeria

Health, 2017, 9, 88-105 http://www.scirp.org/journal/health ISSN Online: 1949-5005 ISSN Print: 1949-4998 Perception of Adolescents on the Attitudes of Providers on Their Access and Use of Reproductive Health Services in Delta State, Nigeria Andrew G. Onokerhoraye, Johnson Egbemudia Dudu* Centre for Population and Environmental Development, Benin City, Nigeria How to cite this paper: Onokerhoraye, Abstract A.G. and Dudu, J.E. (2017) Perception of Adolescents on the Attitudes of Providers This paper examines the perception of adolescents on the attitudes of provi- on Their Access and Use of Reproductive ders on their access and use of reproductive health services (ARHS) in Delta Health Services in Delta State, Nigeria. State, Nigeria, with a view of assessing the impact of providers’ attitude on the Health, 9, 88-105. use of adolescents’ reproductive health services in Delta State. The study http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/health.2017.91007 adopted a survey design to collect primary data using questionnaires and fo- Received: November 2, 2016 cus group discussions (FGDs) from adolescents in a sample of schools. A Accepted: January 10, 2017 sample size of 1500 respondents was taken from 12 schools in six Local Published: January 13, 2017 Government Areas in three Senatorial Districts in Delta State, Nigeria. The Copyright © 2017 by authors and locations of the schools were such that six each were in rural and urban Scientific Research Publishing Inc. communities respectively. The result from the study was that unfriendly atti- This work is licensed under the Creative tudes of providers which keep adolescents waiting, inadequate duration of Commons Attribution International consultations, judgmental attitudes of some providers, lack of satisfactory ser- License (CC BY 4.0). -

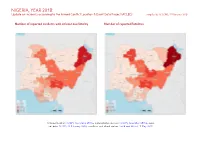

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 22 February 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 705 566 2853 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 474 373 2470 Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 2 Protests 427 3 3 Riots 213 61 154 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 117 3 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 100 84 759 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 2036 1090 6243 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). 2 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Financial Statement Year 2017

Report of the Auditor- General (Local Government) on the December 31 Consolidated Accounts of the twenty-five (25) Local Governments of Delta State for the year 2017 ended Office of the Auditor- General (Local Government), Asaba Delta State STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY It is the responsibility of the Chairmen, Heads of Personnel Management and Treasurers to the Local Government to prepare and transmit the General Purpose Financial Statements of the Local Government to the Auditor-General within three months after 31st December in each year in accordance with section 91 (4) of Delta State Local Government Law of 2013(as amended). They are equally responsible for establishing and maintaining a system of Internal Control designed to provide reasonable assurance that the transactions consolidated give a fair representation of the financial operations of the Local Governments. Report of the Auditor-General on the GPFS of 25 Local Governments of Delta State Page 2 AUDIT CERTIFICATION I have examined the Accounts and General Purpose Financial Statements (GPFS) of the 25 Local Governments of Delta State of Nigeria for the year ended 31st December, 2017 in accordance with section 125 of the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999, section 5(1)of the Audit Law No. 10 of 1982, Laws of Bendel State of Nigeria applicable to Delta state of Nigeria; Section 90(2) of Delta State Local Government Law of 2013(as amended) and all relevant Accounting Standards. In addition, Projects and Programmes were verified in line with the concept of performance Audit. I have obtained the information and explanations required in the discharge of my responsibility. -

Against Malaria Foundation LLIN Distribution Programme – Detailed Information

Against Malaria Foundation LLIN Distribution Programme – Detailed Information Summary # of LLINS Country Location When By whom Sept- Oct 20,000 Nigeria Delta State NDDI/YDI 2010 Further Information 1. Please describe the specific locations & villages to receive nets and the number to each? Please provide longitude/latitude information. (Important note: If the distribution is approved, approval will be for the nets to be distribution to these specific locations. Location changes will only be considered, and may be refused, if due to exceptional/unforeseen circumstances.) The distribution is to take place in Delta State, Nigeria in the following Wards: (1) Ward in Ethiope East LGA (Orhuakpo Ward), (2) Ward in Warri South LGA (Bowen Ward),(3) Wards in Bomadi LGA WOMEN LGA (20%) settlements Wards REQUIRED 5YRS of < of (5%) population OF LLINs PREGNANT Name OF Total numbers TOTAL POPLN Total POPLN BOMADI Akugbene(1) 4 1695 339 85 678 Akugbene(2) 2 6110 1222 306 2444 Akugbene(3) 5 2833 567 142 1133 (Ijaw community) 4255 ETHIOPE 3067 767 EAST Orhaorpor 16 15335 6134 (Urhobo community) Isiokolo 2 9485 1897 474 3794 9928 WARRI SOUTH Bowen 9 14020 2804 701 5608 Total LLIN Requirement 19791 Page 1 of 6 2. Is this an urban or rural area and how many people live in this specific area? The areas represent Rural, Urban and Peri-urban environments with a total population of approx 50,000 (as in the Table) 3. Is this a high risk malaria area? If yes, why do you designate it as high? Accurate local statistics are scarce but empirical evidence suggests that the above environmental factors combined with a high population density and lack of adequate access to medical facilities increase the national statistical average. -

Profitability Analysis of Yam Production in Ika South Local Government Area of Delta State, Nigeria

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X (Online) Vol.3, No.2, 2013 Profitability Analysis of Yam Production in Ika South Local Government Area of Delta State, Nigeria Ebewore Solomon Okeoghene, 1 Egbodion John 2& Oboh Optimist Ose 1 1Delta State University, Asaba Campus Delta State, Nigeria Phone: +2347067389635 2University of Benin, Benin City Edo State, Nigeria Phone: +23476342759 E-mail of corresponding author:[email protected] Abstract The study evaluates the profitability of yam production in Ika South Local Government Area of Delta State, Nigeria. The specific objectives were to: ascertain the socio-economic characteristics of yam producers; determine the productivity of yam; determine the profitability of yam production; and identify the major constraints to the production of yam. Twenty four farmers were randomly selected from each of the five clans randomly selected, thus bringing the sample size to 120. Well-structured and validated questionnaires were administered to obtain information from the farmers. Descriptive statistics was used to analyze the productivity of yam output. Gross margin analysis was used to determine the profitability of yam production. The t-test results showed that the profit level in the production of yam was significantly greater than zero. Lack of credit, inadequate preservation facilities, inadequate or low patronage by wholesalers and low price of yam are the major constraints facing yam producers in the study area. From the findings, it was recommended that Government should ease transportation and provide storage facilities so as to improve the welfare of both sellers and buyers. Keywords : Profitability, production, gross margin, constraint, Delta State 1. -

39. Variability of Voting Pattern Among

Variability of Voting Pattern among Ethnic Nationality in the 2015 Gubernatorial Elections of Delta State IKENGA, F. A. Department of Political Science Faculty of the Social Sciences Delta State University, Abraka, Delta State. E-mail: [email protected] pp 352 - 360 Abstract he study assessed the variability of voting pattern among the different ethnic groups in the 2015 governorship election in Delta State. Data was Tcollected in respect of the votes from the 8 major ethnic groups in the state, and was analyzed accordingly. The hypothesis formulated was tested at 5% level of significance with the aid of the Kruskal- Wallis test. Findings indicate that there was no significant variation in the voting pattern of Deltans across the different ethnic groups. This simply indicates that ethnicity did not influence the results of the 2015 governorship election in Delta State. Given this result, the study recommended that the winner of the 2015 governorship election should form an all-inclusive government and ensure that no ethnic group experience any form of marginalization. Government should also strive to sustain unity among the various ethnic groups in the State by ensuring good governance at all facets and levels. Key words: Voting Pattern, Ethnicity, Election, Delta State, Governance Nigerian Journal of Management Sciences Vol. 6 No.1, 2017 353 Introduction the total votes casted in their ethnic localities. Several The problem of ethnicity/ culture is a global issue and analysts have argued that the political behaviour of not a Nigerian phenomenon. It has been and is still some Nigeria is influenced heavily by the hyperbolic been experienced in both developing and developed assumption that one's destiny is intrinsically and nations. -

Solving the Problem of Unemployment in Delta

IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS) e-ISSN: 2319-2380, p-ISSN: 2319-2372.Volume 7, Issue 1, Ver. IV (Feb. 2014), PP 97-100 www.iosrjournals.org Reducing Unemployment in Delta State through Agricultural Extension and Management Programme: A Case Study of Delta State Polytechnic Ozoro Tibi K.N. and Adaigho D.O. Abstract: This study was carried out in Delta State to examine, how unemployment in Delta State can be reduced through Agricultural Extension and Management programme. A purposive sampling technique was implored to select all the student of HND 1 and HND11 (2012/2013 session) from the Department of Agricultural Extension and Management .Distribution of respondents were HND I was 35 and HND 11 was 38. Data collected with the questionnaires were carefully assembled. The results obtained were systematically and scientifically organized and presented in tables. The simple percentage was used to present data. Data was analyzed by simple mathematical computation. The findings from the study reveals that: the courses in Agricultural Extension and Management Programme are skill oriented; managerial courses, general studies, communication and computer skills among others are courses taught in Agricultural Extension and Management Programme: computer and communicating skills are necessary skills for managerial and productive potential; the actual problems faced in the program are lack /inadequate equipment and insufficient time for practical works; concerted effort has not been made to remedy the problems encounter in the program; and finally Agricultural Extension and Management programme is practically driven and would help to build managerial and productive skills of its graduates who can either be gainfully employed by government and organization on graduation or be self-employed. -

Conflict Bulletin: Delta State

The Fund for Peace Conflict Bulletin: Delta State July 2014 Now, after two years, LGA-level elections are expected to take place on October 25, LGA Level Summary 2014. During 2012 and 2013, reported incidents included gang violence, criminality, 2012-2014 and vigilante/mob justice. Aniocha North/South There were a number of abductions, some targeting political figures, their family As in other parts of Delta State, much of the members, or oil workers. There were violence in the reported time period in several reports of alleged abuses by public Aniocha North and South was associated security forces, which sometimes provoked with kidnappings and criminality. In August mob violence and protest. Conflict risk 2012, nearly 40 lawyers barricaded the factors continued into mid-2014 with magistrates’ courts to protest the abduction reports of abductions and communal of a newly appointed judge. In December violence. 2012, the mother of the Minister of Finance elta is the second most populous was reportedly kidnapped for ransom in state in the Niger Delta, with an This Conflict Bulletin provides a brief Aniocha South. Violence around estimated 4.1 million people. The snapshot of the trends and patterns of kidnappings and robberies increased in state produces about 35% of conflict risk factors at the State and LGA 2013, resulting in several reported deaths Nigeria’s crude oil and a considerable levels, drawing on the data available on the throughout the year. In 2013, there were amount of its natural gas. It is also rich in P4P Digital Platform for Multi-Stakeholder two reported incidents of bank robberies root and tuber crops, such as potatoes, Engagement (www.p4p-nigerdelta.org). -

Conflict Incident Monthly Tracker

Conflict Incident Monthly Tracker Delta State: May -J un e 201 8 B a ck gro und Cult Violence: In April, a 26-year old man in Ofagbe, Isoko South LGA. was reportedly killed by cultists in Ndokwa This monthly tracker is designed to update Other: In May, an oil spill from a pipeline West LGA. The victim was a nephew to the Peace Agents on patterns and trends in belonging to an international oil company chairman of the community's vigilante reportedly polluted several communities in conflict risk and violence, as identified by the group. In May, a young man was reportedly Burutu LGA. Integrated Peace and Development Unit shot dead by cultists at a drinking spot in (IPDU) early warning system, and to seek Ughelli North LGA. The deceased was feedback and input for response to mitigate drinking with friends when he was shot by Recent Incidents or areas of conflict. his assailants. Issues, June 2018 Patterns and Trends Political Violence: In May, a male aspirant Reported incidents during the month related M arch -M ay 2 018 for the All Progressives Congress (APC) ward mainly to communal conflict, criminality, cult chairmanship position was reportedly killed violence, sexual violence and child abuse. According to Peace Map data (see Figure 1), during the party’s ward congress in Ughelli Communal Conflict: There was heightened there was a spike in lethal violence in Delta South LGA. tension over a leadership tussle in Abala- state in May 2018. Reported incidents during Unor clan, Ndokwa East LGA. Tussle for the the period included communal tensions, cult Violence Affecting Women and Girls traditional leadership of the clan has violence, political tensions, and criminality (VAWG): In addition to the impact of resulted in the destruction of property.