Download (2063Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book by Winnie Holzman

Libretto Book Wicked A New Musical Music and Lyrics by Stephen Schwartz Book by Winnie Holzman Based on the novel Wicked: The Life and Times of The Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire Originally Directed by Joe Mantello Originally Produced on Broadway by Marc Platt, Universal Pictures, The Araca Group, Jon B. Platt and David Stone HTTP://COPIONI.CORRIERESPETTACOLO.IT Wicked Cast: Glinda Kristin Chenoweth Elphaba Idina Menzel Fiyero Norbert Leo Butz Nessarose Michelle Federer Boq Christopher Fitzgerald The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Joel Grey Madame Morrible Carole Shelley Doctor Dillamond William Youmans Ensemble Kristy Cates Melissa Bell Chait Marcus Choi Kristoffer Cusick Kathy Deitch Melissa Fahn Rhett G. George Manuel Herrera Kisha Howard LJ Jellison Cristy Candler Sean McCourt Corinne McFadden Jan Neuberger Walter Winston Oneil Andrew Palermo Andy Pellick Michael Seelbach Lorna Ventura Ioana Alfonso Ben Cameron HTTP://COPIONI.CORRIERESPETTACOLO.IT ACT I [Scene 1 - No One Mourns The Wicked] Ozians: GOOD NEWS, SHE'S DEAD! THE WITCH OF THE WEST IS DEAD! THE WICKEDEST WITCH THERE EVER WAS, THE ENEMY OF ALL OF US HERE IN OZ, IS DEAD! GOOD NEWS! GOOD NEWS! Ozian: Look, it's Glinda! (Glinda floats in on a giant bubble) Glinda: It's good to see me, isn't it? (Ozians Agree) No need to respond that was rhetorical. Fellow Ozians, LET US BE GLAD, LET US BE GRATEFUL, LET US REJOICIFY THAT GOODNESS COULD SUBDUE THE WICKED WORKINGS OF YOU KNOW WHO! ISN'T IT NICE TO KNOW THAT GOOD WILL CONQUER EVIL? THE TRUTH WE ALL BELIEVE'LL BY AND BY OUTLIVE A LIE FOR YOU AND.. -

The Wizard of Oz 4Th-8Th Grades

Study Guide: The Wizard of Oz 4th-8th Grades Created as part of the Alliance Theatre’s Dramaturgy by Students program by: Barry Stewart Mann, Teaching Artist with: students at The Friends School of Atlanta and their educator: Ms. Amy Lighthill Written by L. Frank Baum Music and lyrics by Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg Book adaptation by John Kane Directed by Rosemary Newcott March 9 – April 14, 2019 Rich Theatre, Woodruff Arts Center 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pre- and Post-Show Questions ________________________________________________ pg. 3 About the Director __________________________________________________________ pg. 4 Curriculum Standards _______________________________________________________ pg. 5 Synopsis __________________________________________________________________ pg. 5 About the Author ___________________________________________________________ pg. 6 About the Film ____________________________________________________________ pg. 6 • Fun Film Facts ____________________________________________________ pg. 7 • The Wizard of Oz Time Line _________________________________________ pg. 8 Character Profiles on Oztagramchatbook _______________________________________ pg. 9 Folk Art __________________________________________________________________ pg. 10 Themes • (There’s No Place Like) Home ________________________________________ pg. 11 • (Somewhere Over the) Rainbow ______________________________________ pg. 12 • The Hero’s Journey (a Debate) _______________________________________ pgs. 13-14 STEAM Connections _________________________________________________________ -

THE WACKY WIZARD of OZ by Patrick Dorn

THE WACKY WIZARD OF OZ By Patrick Dorn Copyright © 2015 by Patrick Dorn, All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-60003-837-2 CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this Work is subject to a royalty. This Work is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention and the Berne Convention. RIGHTS RESERVED: All rights to this Work are strictly reserved, including professional and amateur stage performance rights. Also reserved are: motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information and storage retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into non-English languages. PERFORMANCE RIGHTS AND ROYALTY PAYMENTS: All amateur and stock performance rights to this Work are controlled exclusively by Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. No amateur or stock production groups or individuals may perform this play without securing license and royalty arrangements in advance from Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Questions concerning other rights should be addressed to Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Royalty fees are subject to change without notice. Professional and stock fees will be set upon application in accordance with your producing circumstances. Any licensing requests and inquiries relating to amateur and stock (professional) performance rights should be addressed to Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Royalty of the required amount must be paid, whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. -

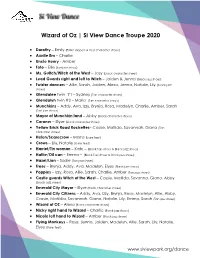

Si View Dance Troupe 2020

Wizard of Oz | Si View Dance Troupe 2020 Dorothy – Emily (Ballet slippers & Red character shoes) Auntie Em – Charlie Uncle Henry - Amber Toto – Ellie (tan jazz shoes) Ms. Gultch/Witch of the West – Josy (black character shoes) Lead Guards right and left to Witch – Jaiden & Jenna (black jazz shoes) Twister dancers – Allie, Sarah, Jaiden, Alexa, Jenna, Natalie, Lily (black jazz shoes) Glendalee twin #1 – Sydney (Tan character shoes) Glendalyn twin #2 – Maria (Tan character shoes) Munchkins – Addy, Ava, Izzy, Brynja, Rosa, Madelyn, Charlie, Amber, Sarah (Tan jazz shoes) Mayor of Munchkin land – Abby (black character shoes) Coroner – Elyse (black character shoes) Yellow Brick Road Rockettes– Cassie, Matilda, Savannah, Giana (Tan character shoes) Helen/Scarecrow – Marra (bare feet) Crows – Lily, Natalie (bare feet) Harriet/Tin woman – Kate – (Black Tap shoes & Black jazz shoes) Hattie/Oil can – Emma – (Black Tap shoes & Black jazz shoes) Hazel/Lion – Sadie (Tan jazz shoes) Trees – Brynja, Addy, Ava, Madelyn, Elyse (Black jazz shoes) Poppies – Izzy, Rosa, Allie, Sarah, Charlie, Amber (Tan jazz shoes) Castle guards Witch of the West – Cassie, Matilda, Savanna, Giana, Abby (black jazz shoes) Emerald City Mayor – Elyse (Black character shoes) Emerald City Citizens – Addy, Ava, Izzy, Brynja, Rosa, Madelyn, Allie, Abby, Cassie, Matildia, Savannah, Giana, Natalie, Lily, Emma, Sarah (Tan jazz shoes) Wizard of OZ – Alexa (Black character shoes) Nicky right hand to Wizard – Charlie (Black jazz shoes) Nicole left hand to Wizard – Amber (Black jazz shoes) Flying Monkeys – Rosa, Jenna, Jaiden, Madelyn, Allie, Sarah, Lily, Natalie, Elyse (Bare feet) www.siviewpark.org/dance Parts for each dancer: 1. Giana – Road Rockette, castle guard, ECC 2. -

Twister Unleashes Fury on TCU Campus Tornado Tornado Damages Procedures Unclear Campus, Apartments

DICAPRIO SOARS IN 'BASKETBALL DIARIES' - PAGE 6 TCU DAILY SKIFF FRIDAY, APRIL 21,1995 TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY, FORT WORTH. TEXAS 92NDYEAR, NO.105 Twister unleashes fury on TCU Campus tornado Tornado damages procedures unclear campus, apartments BY KIMBERLY WILSON BY CHRIS NEWTON TCU DAILY SKIFF TCU DAILY SKIFF Several TCU students and professors said they were In the wake of a tornado some witnesses said confused about official university instructions for tor- touched down several times around the TCU campus. nado warnings after a tornado touched down near cam- Physical Plant officials estimate between S25.000 and pus Wednesday night. S40.000 of damage was done to university property. Heather Novak, a sophomore psychology major, was Andy Kesling, associate director of the Office of taking American and Texas Government with Richard Communications, said the university had extensive Millsap, an adjunct professor in political science, at damage. 8:30 p.m. when a student interrupted class with an "The roof of the Miller Speech and Hearing Clinic announcement that the university had cancelled classes was damaged, two lights were damaged at Amon for the evening. Carter stadium and 15 to 20 trees were damaged." Novak said the civil defense warning was inaudible Kesling said. "One (tree) was completely uprooted." in the Moudy Building. Kesling said university officials were still assessing "We didn't know what was going on," Millsap said. the damage. "I gave my students the option that they could leave or Wednesday night. Skiff reporters and photographers they could stay with me." witnessed the aftermath of the storm and reported that Millsap said all of his students left, so he went home. -

Table of Contents

I table of Contents: Letter fro m the Producer ..... ...2 Before you Go .................. ...... ....... .... .... ... ..... .... 34 Theater Etiquette ..... ..... ....... ... ... ....... ....... ...... ...... ..... ................. Scemc. Breakdown ······ . .... .... 5 Synopsis ······· ..... ...... ........ ...... ........ ...... ....... ..... ...... ········ 6&7 About the Author ...... ....... ...... ..... ··········· . ... 8 After the Show ...... ...... ..... ············ . ... 9 Interdisctplmary. Activities ...... ..... ······ ..10 & 11 Acrostic ··········· ..... ....... ..... ...... .12 Think Theatrically ...... ..... ... ... ....... ...... ....... ... .... ..... ..... ........ ..... 13 Fan Letter ...... ..... ................ ..... 14 Theater Vocabulary ....... ...... .. .... .... .. ...... ...... ....... ..... .. .. .. ...... ..... .15 ...... ..... ...... .. .... ..... .16 Write a Review .............................. ...... 17 ............ .. ·······. ..... 18 Careers in the Arts . .................................... Wo rd Search . .. .. ............................. ..... 19 Draw a Picture ........ ...... ...... ...... ....... .. ..... 2 Dear Educator: This guide contains suggested learning experiences for various grade levels. It is intended to help your students enjoy and utilize the theater-going experience. Please select those ideas that best relate to your curriculum and classroom needs. We would appreciate knowing which suggestions you actually incorporated into your lesson plans and how they worked for you. Share your -

Critical and Creative Approaches Ed. Jan Shaw, Philippa Kelly, LE Semler

Published in Storytelling: Critical and Creative Approaches ed. Jan Shaw, Philippa Kelly, L. E. Semler (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2013), pp. 83-113. Transnational Glamour, National Allure: Community, Change and Cliché in Baz Luhrmann’s Australia. Meaghan Morris What are the links between stories and the wider social world—the contextual conditions for stories to be told and for stories to be received? What brings people to give voice to a story at a particular historical moment? … and as the historical moment shifts, what stories may lose their significance and what stories may gain in tellability? (Plummer 25). The vantage points from which we customarily view the world are, as William James puts it, ‘fringed forever by a more’ that outstrips and outruns them (Jackson 23-24). Poetry from the future interrupts the habitual formation of bodies, and it is an index of a time to come in which what today exists potently—even if not (yet) effectively— but escapes us will find its time. (Keeling, ‘Looking for M—’ 567) 1 The first time I saw Baz Luhrmann’s Australia I laughed till I cried. To be exact, I cried laughing at dinner after watching the film with a group of old friends at an inner suburban cinema in Sydney. During the screening itself I laughed and I cried. As so often in the movies, our laughter was public and my tears were private, left to dry on my face lest the dabbing of a tissue or an audible gulp should give my emotion away. The theatre was packed that night with a raucously critical audience groaning at the dialogue, hooting at moments of high melodrama (especially Jack Thompson’s convulsive death by stampeding cattle) and cracking jokes at travesties of history perceived on screen. -

2-Year-Old Filly Trotters

2-YEAR-OLD FILLY TROTTERS Leg 1 Leg 2 Leg 3 Leg 4 ELIGIBLE HORSES Sire Dam NP 7/3 SD 7/20 NP 8/6 SD 8/28 Allaboutadream X X X X Uncle Peter Inevitable All Along X X X X Dejarmbro Nantab All For You X X X X Uncle Peter Nordic Nymph All Of China X X X X Dejarmbro Great Hall of China And Many More X X X X Manofmanymissions Cavier N Chardoney And Up We Go X X X X And Away We Go Miss Giai D Aunt Bee's Jewel X X X X Uncle Peter Keep Me In Mind Auntie Percilla X X X X Uncle Peter I Lazue Aunt Marilynn X X X X Uncle Peter Poster Pin Up Aunt Rose X X X X Uncle Peter Lightning Flower Aunt Suzanna X X X X Uncle Peter Aleah Hanover Back Splash X X X X Triumphant Caviar Splashabout Bad Babysitter X X X X Manofmanymissions My Baby's Momma Bank On Tiffany X X X X Break The Bank K Tiffany Bella MacDuff X X X X Manofmanymissions Whata Star Bentontriumph X X X X Triumphant Caviar Bentley Seelster Beyond Amazing X X X X Dontyouforgetit Pine Career Box Cars X X X X Manofmanymissions Prettysydney Ridge Brandy Fine Girl X X X X Dontyouforgetit Yankeedoodledandy Break Hearts X X X X Break The Bank K Sweetie Hearts Breakthemagic X X X X Break The Bank K Magic Peach Broadway Mimi X X X X Broadway Hall Mini Marvelous Bye Bye Broadway X X X X Broadway Hall Classy Messenger Caia X X X X Manofmanymissions Cedada Caring Moment X X X X Uncle Peter Emotional Rescue Cash In The Chips X X X X Break The Bank K Miss Chip K Cathy Jo's Triumph X X X X Triumphant Caviar Winter Green CC Cashorcredit X X X X Dejarmbro Take Em Cash Counting Her Moni X X X X Break The Bank K Sheknowsherlines -

ULIV Alumni 2020.Indd

ALUMNI TIME FOR A SEA CHANGEOur response to the global climate crisis INSIDE YOUR 2020 EDITION: ❱ Change is coming to campus ❱ Alumni Award winners 2019 ❱ Pioneering in public health ❱ CONTENTS 04 News Vice-Chancellor Professor Dame ALUMNI 20 18 Janet Beer introduces a round-up of In Case of The Yorkshire Vet campus news ver the past year, we have Emergency, Peter Wright, the star of Channel 5’s welcomed many new Break Habits The Yorkshire Vet, reminisces on his 16 Award winners members to the team to Celebrating University of Liverpool O The University of time as a student take a lead on engaging with our alumni and their worldwide impact recent graduates and international Liverpool is transforming networks, managing our to fit into a sustainable 26 Passports to volunteering programme and future – and everyone Possibilities developing our fundraising appeals. has a role to play Driving forward with our commitment In my new role as Head of Alumni to global education Engagement, it has also been a great honour to take the helm as editor of your Alumni magazine. 27 Legacies The theme of this year’s magazine is ‘facing global Highlighting the enormous challenges’ - from alumna Professor Louise Kenny (MBChB contribution made by our legacy Hons 1993) who is leading on the University’s commitment supporters to improving the health of people in the Liverpool region and beyond, to our research and impact in the areas of climate 28 Class Notes change and sustainability. What happened to your classmates Read on to hear about the winners of our inaugural Alumni after graduation? Awards, which recognise the many and varied achievements 34 In memoriam of our alumni community. -

CT HS Performing Arts Center THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 7:30PM SATURDAY, JANUARY 28, 7:30PM MONDAY, JANUARY 30, 7:30PM the WIZARD of OZ by L

Chisholm Trail High School Fine Arts Present CT HS Performing Arts Center THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 7:30PM SATURDAY, JANUARY 28, 7:30PM MONDAY, JANUARY 30, 7:30PM THE WIZARD OF OZ By L. Frank Baum With Music and Lyrics by Harold Arlen and E. Y. Harburg Background Music by Herbert Stothart Dance and Vocal Arrangements by Peter Howard Orchestration by Larry Wilcox Adapted by John Kane for the Royal Shakespeare Company Based upon the Classic Motion Picture owned by Turner Entertainment Co. and distributed in all media by Warner Bros. Directed by Jesse Esquierdo and Carla Hardy Orchestra Director—Jared Hardy Orchestra Organizers—John Canfield and Hannah Stephens Set and Technical Director—Jeremy Beck Lighting Design—Jesse Esquierdo and Deleon Mejia Costuming—Carla Hardy and Costumes by Dusty Jitterbug Choreography—Lindsey Lindley and Britton Melton Backdrops—Paul Randall and Carla Hardy Foyer Décor—Melanie Bell and Michaela Hanna THE WIZARD OF OZ is presented by arrangement with TAMS-WITMARK MUSIC LIBRARY, INC. 560 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York 10022 (212) 688-2525 www.tamswitmark.com SCENES AND MUSICAL NUMBERS ACT ONE Scene 1: Kansas Prairie...........................................................................................Narrators and Orchestra Scene 2: The Rainbow....................................................................................................“Over the Rainbow” Dorothy Scene 3: Kansas.................................................Miss Gulch, Aunt Em, Uncle Henry, Hickory, Hunk, Zeke Scene 4: Gypsy Caravan............................................................................................Dorothy -

Letterstoyoungerme in Support of the Roald Dahl Nurses Appeal

#LettersToYoungerMe in support of the Roald Dahl Nurses Appeal www.roalddahlcharity.org/donatewww.roalddahlcharity.org/donate My Roald Dahl Transition I firmly believe that every NHS Trust in the UK Specialist Nurse, Giselle has should have a Roald Dahl Transition Specialist helped me come to terms Nurse. Without this role, I firmly believe my son’s with becoming an adult and health would have been negatively impacted sees me as a person, not just Virginia, mum to Ben (who has Sickle Cell Disease) my condition. was supported by Roald Dahl Specialist Transition Nurse, Giselle as he moved from child to adult services Ben (25) Transition Roald Dahl’s Marvellous It’s a funny old thing, isn’t it – and on the face of There are more than 80 Roald Dahl Specialist it, it looks like it will be straight forward. Nurses based within the NHS in England, Children’s Charity Go to sleep a child, wake up a young adult. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. After all, what difference can a few hours We know that a smooth and safe transition We are appealing for donations to help establish We provide specialist nurses and make? Apart from maybe now as an adult you means young people will have better health can be more independent. outcomes, and that parents, carers and more vital Roald Dahl Transition Specialist Nurses support for seriously ill children. But we all know it’s trickier than that, especially families will be supported too. It’s one less to support more young people across the UK. Our network of 82 Roald Dahl if you have the additional complexity of being thing to worry about at a time where there are In support of our appeal, a star-studded host Specialist Nurses support over under the care of doctors and nurses. -

FOUR MAJOR NEW DRAMAS COMMENCE FILMING in BRISTOL in APRIL Including Showtrial, the New Title from Line of Duty Producers

NEWS: For immediate release FOUR MAJOR NEW DRAMAS COMMENCE FILMING IN BRISTOL IN APRIL including Showtrial, the new title from Line of Duty producers BRISTOL, 23 April 2021: Four major new dramas – Showtrial, The Girl Before and Chloe for the BBC and The Long Call for ITV - have commenced filming in Bristol this month, as the city continues to attract a consistent flow of film and TV productions to use its locations, studio space and filming support services. Laura Aviles, Senior Bristol Film Manager for Bristol City Council responsible for The Bottle Yard Studios & Bristol Film Office, says: “Four major dramas beginning their shoots in Bristol in the space of just a few weeks is a clear indication of the city’s appeal to producers right now. With Showtrial, Chloe, The Girl Before and The Long Call joining other titles already actively filming in the city, Bristol is continuing the exceptionally strong levels of High-End TV production we saw in the first quarter of this year well into the second quarter, bringing welcome benefits to local crew, facilities and service companies, and creating numerous other knock-on benefits to the city’s economy.” SHOWTRIAL From World Productions (Line of Duty, Bodyguard, The Pembrokeshire Murders) comes Showtrial, a brand new drama for BBC One and BBC iPlayer from writer Ben Richards (The Tunnel, Strike, Cobra). Described as “a timely legal drama full of dark humour,” Showtrial is filmed and set around Bristol, and explores how prejudice, politics and the media distort the legal process. The five-part series’ production team is based at The Bottle Yard Studios and filming is taking place on location in Bristol, with assistance from Bristol Film Office.