Representation and Local People's Congresses In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

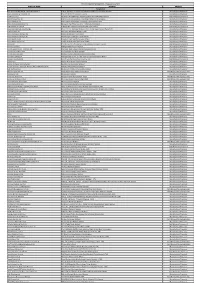

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

Area/Temperature Limitation to Application of Vetiver System in China

Adequate Areas in China for the Application of Vetiver System Liyu XU (China Vetiver Network, Nanjing 210008) Abstract: Vetiver System was introduced into China by Mr. Grimshaw from the World Bank in 1988. Beginning from the Fuzhou Symposium in 1997, the system was applied for infrastructure protection in China. Since the Nanchang Symposium in 1999, it was extended quickly countrywide, and in particular, it was extensively applied and extended in South China. On the basis of reviewing successful research cases all over China, this paper deals with adequate areas where vetiver grasses can be planted, and lists related issues that should be further studied in the future. Key words: Vetiver system, Slope protection, Adequate planting area Environment protection is one of the most urgent missions faced by the contemporary world and also one of the basic tasks faced by the Chinese people in their economical construction and social development. Therefore, it should be considered as a basic state policy to be adhered in a long historic period. In its broad sense, environment protection consists of two fields, i.e., soil and water conservation as well as pollution control. To practice environment protection, various measures may be adopted. However, among those measures, bioengineering technology has been becoming favorite one frequently adopted by more and more people in recent years. Vetiver (Vetiveria zizanioides) is characterized by its strong stress tolerance, wide adoptability, quick growing vitality, huge biomass, highly developed root system with fantastic mechanical properties, and powerful soil bounding capacity as well as is to be easily planted and simply managed at very low cost. -

Habitat Specialisation in the Reed Parrotbill Paradoxornis Heudei Evidence from Its Distribution and Habitat

FORKTAIL 29 (2013): 64–70 Habitat specialisation in the Reed Parrotbill Paradoxornis heudei—evidence from its distribution and habitat use LI-HU XIONG & JIAN-JIAN LU The Reed Parrotbill Paradoxornis heudei is found in habitats dominated by Common Reed Phragmites australis in East Asia. This project was designed to test whether the Reed Parrotbill is a specialist of reed-dominated habitats, using data collected through literature review and field observations. About 87% of academic publications describing Reed Parrotbill habitat report an association with reeds, and the species was recorded in reeds at 92% of sites where it occurred. On Chongming Island, birds were only recorded in transects covered with reeds or transects with scattered reeds close to large reedbeds. At the Chongxi Wetland Research Centre, monthly monitoring over three years also showed that the species was not recorded in habitats without reeds. The density of Reed Parrotbills was higher in reedbeds than mixed vegetation (reeds with planted trees) and small patches of reeds. The species rarely appeared in mixed habitat after reeds disappeared. These results confirm that the species is a reed specialist and highlights that conservation of reed-dominated habitat is a precondition to conserve the Reed Parrotbill. INTRODUCTION METHODS Habitat specialisation results in some species having a close Three sets of information on Reed Parrotbill distribution and relationship with only a few habitat types (Futuyma & Moreno habitat use were used: (1) distribution and habitat use data in the 1988), and habitat specialists have some specific life-history Chinese part of its range, collated from academic publications, web characteristics, for example, they often have weak dispersal abilities news, communication with birdwatchers and personal (Krauss et al. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS M Ns Garments Printing & Embroidery

TIER 2 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced July 2021 TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS Bangladesh Mns Garments Printing & Embroidery (Unit 2) House 305 Road 34 Hazirpukur Choydana National University Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor (A&E) American & Efird (Bd) Ltd Plot 659 & 660 93 Islampur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor A G Dresses Ltd Ag Tower Plot 09 Block C Tongi Industrial Area Himardighi Gazipur Next Branded Component Abanti Colour Tex Ltd Plot S A 646 Shashongaon Enayetnagar Fatullah Narayanganj Manufacturer/Processor Aboni Knitwear Ltd Plot 169 171 Tetulzhora Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1340 Manufacturer/Processor Afrah Washing Industries Ltd Maizpara Taxi Track Area Pan - 4 Patenga Chottogram Manufacturer/Processor AKM Knit Wear Limited Holding No 14 Gedda Cornopara Ulail Savar Dhaka Next Branded Component Aleya Embroidery & Aleya Design Hose 40 Plot 808 Iqbal Bhaban Dhour Nishat Nagar Turag Dhaka 1230 Manufacturer/Processor Alim Knit (Bd) Ltd Nayapara Kashimpur Gazipur 1750 Manufacturer/Processor Aman Fashions & Designs Ltd Nalam Mirzanagar Asulia Savar Manufacturer/Processor Aman Graphics & Design Ltd Nazimnagar Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Sweaters Ltd Rajaghat Road Rajfulbaria Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Winter Wears Ltd Singair Road Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Amann Bd Plot No Rs 2497-98 Tapirbari Tengra Mawna Shreepur Gazipur Next Branded Component Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor Ananta Apparels Ltd - Adamjee Epz Plot 246 - 249 Adamjee Epz Narayanganj -

Results Announcement for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

(GDR under the symbol "HTSC") RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Huatai Securities Co., Ltd. (the "Company") hereby announces the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended December 31, 2020. This announcement contains the full text of the annual results announcement of the Company for 2020. PUBLICATION OF THE ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT AND THE ANNUAL REPORT This results announcement of the Company will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism), and the website of the Company (www.htsc.com.cn), respectively. The annual report of the Company for 2020 will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of the National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism) and the website of the Company in due course on or before April 30, 2021. DEFINITIONS Unless the context otherwise requires, capitalized terms used in this announcement shall have the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definitions” in the annual report of the Company for 2020 as set out in this announcement. By order of the Board Zhang Hui Joint Company Secretary Jiangsu, the PRC, March 23, 2021 CONTENTS Important Notice ........................................................... 3 Definitions ............................................................... 6 CEO’s Letter .............................................................. 11 Company Profile ........................................................... 15 Summary of the Company’s Business ........................................... 27 Management Discussion and Analysis and Report of the Board ....................... 40 Major Events.............................................................. 112 Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders .................................... 149 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff.............................. -

Tier 1 Manufacturing Sites

TIER 1 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced January 2021 SUPPLIER NAME MANUFACTURING SITE NAME ADDRESS PRODUCT TYPE No of EMPLOYEES Albania Calzaturificio Maritan Spa George & Alex 4 Street Of Shijak Durres Apparel 100 - 500 Calzificio Eire Srl Italstyle Shpk Kombinati Tekstileve 5000 Berat Apparel 100 - 500 Extreme Sa Extreme Korca Bul 6 Deshmoret L7Nr 1 Korce Apparel 100 - 500 Bangladesh Acs Textiles (Bangladesh) Ltd Acs Textiles & Towel (Bangladesh) Tetlabo Ward 3 Parabo Narayangonj Rupgonj 1460 Home 1000 - PLUS Akh Eco Apparels Ltd Akh Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Albion Apparel Group Ltd Thianis Apparels Ltd Unit Fs Fb3 Road No2 Cepz Chittagong Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Artistic Design Ltd 232 233 Narasinghpur Savar Dhaka Ashulia Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Hameem - Creative Wash (Laundry) Nishat Nagar Tongi Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Aykroyd & Sons Ltd Taqwa Fabrics Ltd Kewa Boherarchala Gila Beradeed Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bespoke By Ges Unip Lda Panasia Clothing Ltd Aziz Chowdhury Complex 2 Vogra Joydebpur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Asrotex Ltd Betjuri Naun Bazar Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Metro Knitting & Dyeing Mills Ltd (Factory-02) Charabag Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Tanzila Textile Ltd Baroipara Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Taqwa -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology ISSN 2616-7433 Vol. 3, Issue 1: 23-35, DOI: 10.25236/FSST.2021.030106 Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta Yuxin Chen, Yuegang Chen Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China Abstract: The city cluster in Yangtze River Delta is the core area of China's modernization and economic development. The industry of Bed and Breakfast (B&B) in this area is relatively developed, and the distribution and spatial pattern of Minshuku will also get much attention. Earlier literature tried more to explore the influence of individual characteristics of Minshuku (such as the design style of Minshuku, etc.) on Minshuku. However, the development of Minshuku has a cluster effect, and the distribution of domestic B&Bs is very unbalanced. Analyzing the differences in the distribution of Minshuku and their causes can help the development of the backward areas and maintain the advantages of the developed areas in the industry of Minshuku. This article finds that the distribution of Minshuku is clustered in certain areas by presenting the overall spatial distribution of Minshuku and cultural attractions in Yangtze River Delta and the respective distribution of 27 cities. For example, Minshuku in the central and eastern parts of Yangtze River Delta are more concentrated, so are the scenic spots in these areas. There are also several concentrated Minshuku areas in other parts of Yangtze River Delta, but the number is significantly less than that of the central and eastern regions. Keywords: Minshuku, Yangtze River Delta, Spatial distribution, Concentrated distribution 1. -

Factory List September 2020 Liste Der Fabriken September 2020 Liste Des

ListeListeFactory der des Fabriken usines List SeptembreSeptember 2020 D06 Factory List 2020.indd 1 15/09/2020 16:28 FactoryNameNom De Der NameL'Usine Fabrik FactoryAnschriftAdresse AddressDe Der L'Usine Fabrik CountryLandPays ProductProdukt-Catégorie NumberAnzahlNombre Der D'EmployésOf Workers % % CategorykategorieDe Produit Beschäftigten*Correct*Données As Mises Of À Jour En FemaleWeiblichFemelle MaleMännMâle - SeptemberJuin 2020 2020 *Zutreffend Mit Wirkung Ab lich September 2020 Afa 3 Calzature Sh.P.K Afa 3 Calzature Sh.p.k, Berat, Albania Albania WW 221 73 27 Grace Glory Garments Preykor Village, Lumhach Commune, Cambodia Mini 2483 90 10 Angsnoul District, Kandal Popmode Dyontex (Ningbo) No 72-106 Gongmao 1 Road, Ishigang China WW, Mini 492 68 32 Limited Industrial Zone, Ningbo, 315171 Zhucheng Tianyao Garment Zangkejia Road, Textile & Garment China Mini 306 79 21 Co. Ltd. Industrial Park, Longdu Sub-District, Zhucheng City, Weifang City, Shandong Province Fujian Tancome Apparel Baijin Industrial Park, Baizhong Town China MW, Mini 161 68 32 Minging Country, Fuzhou City Anhui Baode Clothing Co Economic Zone, Chengdong Town, China Mini 155 79 21 Ltd Yongqiao District, Suzhou City Dezhou Excellent Garment No 16, Geruide Road Dezhou Economic China MW, Mini 260 92 8 Distric, Dezhou City Shandong Province Goldenmine Co Shuanghu Village, Hengcun Town, Tonglu China Mini 44 64 36 County, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province CWG No. 2 Xie Wu First Industry Area, China Mini 19 58 42 Hengshan Village, Shipal Town, Guangdong Ningbo Fenghe No.135 Jinyuan Road, Part B, Economic China Mini 290 85 15 Development, Zhenhai, Ningbo, 315221, Taishan City Taicheng No 106, Qiaohu Road, Taicheng Town, China Mini 172 84 16 Together Garment Factory Taishan City, Guangdong, 529200 Shenzhen Fuhowe Fashion 1-3/F Building, 10 Nangang Industrial Park China WW 221 35 65 Co Ltd Phase 1, Xili, Nanshan District, Shenzhen, 518055 Auro (Xinfeng) Fashion Co No. -

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020 Wei Zhang Xiamen University Jia Rui Xiamen University Xiaoqing Cheng Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Bin Deng Xiamen University Hesong Zhang Xiamen University Lijing Huang Xiamen University Lexin Zhang Xiamen University Simiao Zuo Xiamen University Junru Li Xiamen University XingCheng Huang Xiamen University Yanhua Su Xiamen University Benhua Zhao Xiamen University Yan Niu Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing City, People’s Republic of China Hongwei Li Xiamen University Jian-li Hu Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Tianmu Chen ( [email protected] ) Page 1/30 Xiamen University Research Article Keywords: Hand foot mouth disease, Jiangsu Province, model, transmissibility, effective reproduction number Posted Date: July 30th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-752604/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/30 Abstract Background: Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) has been a serious disease burden in the Asia Pacic region represented by China, and the transmission characteristics of HFMD in regions haven’t been clear. This study calculated the transmissibility of HFMD at county levels in Jiangsu Province, China, analyzed the differences of transmissibility and explored the reasons. Methods: We built susceptible-exposed-infectious-asymptomatic-removed (SEIAR) model for seasonal characteristics of HFMD, estimated effective reproduction number (Reff) by tting the incidence of HFMD in 97 counties of Jiangsu Province from 2015 to 2020, compared incidence rate and transmissibility in different counties by non -parametric test, rapid cluster analysis and rank-sum ratio. -

GH 8 2 V Announcement

Geospatial Health 8(2), 2014, pp. 429-435 Spatial distribution and risk factors of influenza in Jiangsu province, China, based on geographical information system Jia-Cheng Zhang1, Wen-Dong Liu2, Qi Liang2, Jian-Li Hu2, Jessie Norris3, Ying Wu2, Chang-Jun Bao2, Fen-Yang Tang2, Peng Huang1, Yang Zhao1, Rong-Bin Yu1, Ming-Hao Zhou2, Hong-Bing Shen1, Feng Chen1, Zhi-Hang Peng1 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China; 2Jiangsu Province Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China; 3National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, People’s Republic of China Abstract. Influenza poses a constant, heavy burden on society. Recent research has focused on ecological factors associated with influenza incidence and has also studied influenza with respect to its geographic spread at different scales. This rese- arch explores the temporal and spatial parameters of influenza and identifies factors influencing its transmission. A spatial autocorrelation analysis, a spatial-temporal cluster analysis and a spatial regression analysis of influenza rates, carried out in Jiangsu province from 2004 to 2011, found that influenza rates to be spatially dependent in 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2008. South-western districts consistently revealed hotspots of high-incidence influenza. The regression analysis indicates that rail- ways, rivers and lakes are important predictive environmental variables for influenza risk. A better understanding of the epi- demic pattern and ecological factors associated with pandemic influenza should benefit public health officials with respect to prevention and controlling measures during future epidemics.