The Expanding Reach of the Individual Alternative Minimum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

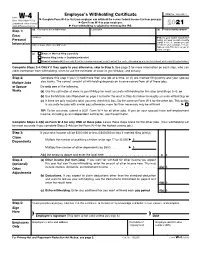

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

The Alternative Minimum Tax

Updated December 4, 2017 Tax Reform: The Alternative Minimum Tax The U.S. federal income tax has both a personal and a Individual AMT corporate alternative minimum tax (AMT). Both the The modern individual AMT originated with the Revenue corporate and individual AMTs operate alongside the Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-600) and operated in tandem with an regular income tax. They require taxpayers to calculate existing add-on minimum tax prior to its repeal in 1982. their liability twice—once under the rules for the regular Table 2 details selected key individual AMT parameters. income tax and once under the AMT rules—and then pay the higher amount. Minimum taxes increase tax payments Table 2. Selected Individual AMT Parameters, 2017 from taxpayers who, under the rules of the regular tax system, pay too little tax relative to a standard measure of Single/ Married their income. Head of Filing Married Filing Household Jointly Separately Corporate AMT Exemption $54,300 $84,500 $42,250 The corporate AMT originated with the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-514), which eliminated an “add-on” 28% bracket 187,800 187,800 93,900 minimum tax imposed on corporations previously. The threshold corporate AMT is a flat 20% tax imposed on a Source: Internal Revenue Code. corporation’s alternative minimum taxable income less an exemption amount. A corporation’s alternative minimum The individual AMT tax base is broader than the regular taxable income is the corporation’s taxable income income tax base and starts with regular taxable income and determined with certain adjustments (primarily related to adds back various deductions, including personal depreciation) and increased by the disallowance of a exemptions and the deduction for state and local taxes. -

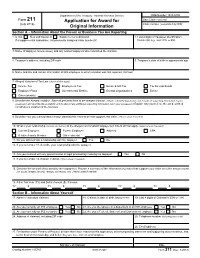

Form 211, Application for Award for Original Information

Department of the Treasury - Internal Revenue Service OMB Number 1545-0409 Form 211 Application for Award for Date Claim received (July 2018) Claim number (completed by IRS) Original Information Section A – Information About the Person or Business You Are Reporting 1. Is this New submission or Supplemental submission 2. Last 4 digits of Taxpayer Identification If a supplemental submission, list previously assigned claim number(s) Number(s) (e.g., SSN, ITIN, or EIN) 3. Name of taxpayer (include aliases) and any related taxpayers who committed the violation 4. Taxpayer's address, including ZIP code 5. Taxpayer's date of birth or approximate age 6. Name and title and contact information of IRS employee to whom violation was first reported, if known 7. Alleged Violation of Tax Law (check all that apply) Income Tax Employment Tax Estate & Gift Tax Tax Exempt Bonds Employee Plans Governmental Entities Exempt Organizations Excise Other (identify) 8. Describe the Alleged Violation. State all pertinent facts to the alleged violation. (Attach a detailed explanation and include all supporting information in your possession and describe the availability and location of any additional supporting information not in your possession.) Explain why you believe the act described constitutes a violation of the tax laws 9. Describe how you learned about and/or obtained the information that supports this claim. (Attach sheet if needed) 10. What is your relationship (current and former) to the alleged noncompliant taxpayer(s)? Check all that apply. (Attach sheet if needed) Current Employee Former Employee Attorney CPA Relative/Family Member Other (describe) 11. Do you still maintain a relationship with the taxpayer Yes No 12. -

Treasury's Upcoming Role in Formulating Tax Policy C

Treasury's Upcoming Role in Formulating Tax Policy C. Eugene Steuerle "Economic Perspective" column reprinted with permission. Document date: October 18, 2002 Copyright 2002 TAX ANALYSTS Released online: October 18, 2002 The nonpartisan Urban Institute publishes studies, reports, and books on timely topics worthy of public consideration. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. © TAX ANALYSTS. Reprinted with permission. It is said that in every crisis is opportunity. In every political crisis, moreover, something will be done -- for good or ill -- to appear to deal with the crisis. While tax policy has generally been run out of the White House for a number of years in both Republican and Democratic administrations, that trend will be forced to reverse itself. Within the Executive Branch, only the Treasury Department is equipped to deal well with the upcoming political crisis surrounding the imposition of the alternative minimum tax on tens of millions of taxpayers. Whether it finds opportunity in this task -- one from which most politicians shy -- remains to be seen. The convoluted nature of our tax system is worthy of reform, but it is not a crisis. The strange imposition of the AMT on so many taxpayers, along with its strong bias against families with children, is a crisis. It is not an economic or even administrative crisis so much as one of politics. The economy can certainly withstand the economic repercussions of this somewhat crazy tax policy, and IRS can certainly administer the tax: At least regarding the major items involved, a computer check will find most errors. -

2021 Instructions for Form 6251

Note: The draft you are looking for begins on the next page. Caution: DRAFT—NOT FOR FILING This is an early release draft of an IRS tax form, instructions, or publication, which the IRS is providing for your information. Do not file draft forms and do not rely on draft forms, instructions, and publications for filing. We do not release draft forms until we believe we have incorporated all changes (except when explicitly stated on this coversheet). However, unexpected issues occasionally arise, or legislation is passed—in this case, we will post a new draft of the form to alert users that changes were made to the previously posted draft. Thus, there are never any changes to the last posted draft of a form and the final revision of the form. Forms and instructions generally are subject to OMB approval before they can be officially released, so we post only drafts of them until they are approved. Drafts of instructions and publications usually have some changes before their final release. Early release drafts are at IRS.gov/DraftForms and remain there after the final release is posted at IRS.gov/LatestForms. All information about all forms, instructions, and pubs is at IRS.gov/Forms. Almost every form and publication has a page on IRS.gov with a friendly shortcut. For example, the Form 1040 page is at IRS.gov/Form1040; the Pub. 501 page is at IRS.gov/Pub501; the Form W-4 page is at IRS.gov/W4; and the Schedule A (Form 1040/SR) page is at IRS.gov/ScheduleA. -

The Viability of the Fair Tax

The Fair Tax 1 Running head: THE FAIR TAX The Viability of The Fair Tax Jonathan Clark A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2008 The Fair Tax 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Gene Sullivan, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Donald Fowler, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ JoAnn Gilmore, M.B.A. Committee Member ______________________________ James Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date The Fair Tax 3 Abstract This thesis begins by investigating the current system of federal taxation in the United States and examining the flaws within the system. It will then deal with a proposal put forth to reform the current tax system, namely the Fair Tax. The Fair Tax will be examined in great depth and all aspects of it will be explained. The objective of this paper is to determine if the Fair Tax is a viable solution for fundamental tax reform in America. Both advantages and disadvantages of the Fair Tax will objectively be pointed out and an educated opinion will be given regarding its feasibility. The Fair Tax 4 The Viability of the Fair Tax In 1986 the United States federal tax code was changed dramatically in hopes of simplifying the previous tax code. Since that time the code has undergone various changes that now leave Americans with over 60,000 pages of tax code, rules, and rulings that even the most adept tax professionals do not understand. -

Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax

The Contemporary Tax Journal Volume 5 Issue 2 Winter 2016 Article 11 2-12-2016 Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax Branden Wilson San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sjsumstjournal Part of the Taxation-Federal Commons, Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift Commons, and the Taxation- Transnational Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Branden (2016) "Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax," The Contemporary Tax Journal: Vol. 5 : Iss. 2 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sjsumstjournal/vol5/iss2/11 This Focus on Tax Policy is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Business at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Contemporary Tax Journal by an authorized editor of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wilson: Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax major difference between the regular income tax and the AMT is that the AMT does not By: Branden Wilson, MST Student allow some of the deductions allowed under the normal tax rules. This makes it stealthy as it creeps up to surprise a taxpayer who is What is the AMT? denied a large state tax deduction allowed under the regular tax rules and becomes a The alternative minimum tax, or AMT, can be victim to a higher tax under the AMT. described as a parallel tax system that operates on a different set of rules. The AMT is an The taxpayers most likely to get pulled into income tax. It affects individuals, the AMT are middle-to-high income earners corporations, estates and trusts. -

Form 1040 Page Is at IRS.Gov/Form1040; the Pub

Note: The draft you are looking for begins on the next page. Caution: DRAFT—NOT FOR FILING This is an early release draft of an IRS tax form, instructions, or publication, which the IRS is providing for your information. Do not file draft forms and do not rely on draft forms, instructions, and publications for filing. We do not release draft forms until we believe we have incorporated all changes (except when explicitly stated on this coversheet). However, unexpected issues occasionally arise, or legislation is passed—in this case, we will post a new draft of the form to alert users that changes were made to the previously posted draft. Thus, there are never any changes to the last posted draft of a form and the final revision of the form. Forms and instructions generally are subject to OMB approval before they can be officially released, so we post only drafts of them until they are approved. Drafts of instructions and publications usually have some changes before their final release. Early release drafts are at IRS.gov/DraftForms and remain there after the final release is posted at IRS.gov/LatestForms. All information about all forms, instructions, and pubs is at IRS.gov/Forms. Almost every form and publication has a page on IRS.gov with a friendly shortcut. For example, the Form 1040 page is at IRS.gov/Form1040; the Pub. 501 page is at IRS.gov/Pub501; the Form W-4 page is at IRS.gov/W4; and the Schedule A (Form 1040/SR) page is at IRS.gov/ScheduleA. -

2016 Tax Brackets FACT Oct

FISCAL 2016 Tax Brackets FACT Oct. 2015 By Kyle Pomerleau No. 486 Economist Introduction Every year, the IRS adjusts more than 40 tax provisions for inflation. This is done to prevent what is called “bracket creep.” This is the phenomenon by which people are pushed into higher income tax brackets or have reduced value from credits or deductions due to inflation, instead of any increase in real income. The IRS uses the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to calculate the past year’s inflation and adjusts income thresholds, deduction amounts, and credit values accordingly. Rather than directly adjusting last year’s values for annual inflation, each provision is adjusted from a specified base year. For more information, see Methodology, below. Estimated Income Tax Brackets and Rates In 2016, the income limits for all brackets and all filers will be adjusted for inflation and will be as follows (Table 1). The top marginal income tax rate of 39.6 percent will hit taxpayers with adjusted gross income of $415,050 and higher for single filers and $466,950 and higher for married filers. Table 1. 2016 Taxable Income Brackets and Rates (Estimate) Rate Single Filers Married Joint Filers Head of Household Filers 10% $0 to $9,275 $0 to $18,550 $0 to $13,250 15% $9,275 to $37,650 $18,550 to $75,300 $13,250 to $50,400 25% $37,650 to $91,150 $75,300 to $151,900 $50,400 to $130,150 The Tax Foundation is a 501(c)(3) 28% $91,150 to $190,150 $151,900 to $231,450 $130,150 to $210,800 non-partisan, non-profit research 33% $190,150 to $413,350 $231,450 to $413,350 $210,800 to $413,350 institution founded in 1937 to 35% $413,350 to $415,050 $413,350 to $466,950 $413,350 to $441,000 educate the public on tax policy. -

2020 Instructions for Form 6251

Userid: CPM Schema: Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 9.5 Draft Ok to Print instrx AH XSL/XML Fileid: … ions/I6251/2020/A/XML/Cycle07/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 13 14:42 - 8-Jan-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Department of the Treasury 2020 Internal Revenue Service Instructions for Form 6251 Alternative Minimum Tax—Individuals Section references are to the Internal Revenue 4. The total of Form 6251, lines 2c and basis amounts may also differ for Code unless otherwise noted. through 3, is negative and line 7 would the AMT. be greater than line 10 if you didn’t take General Instructions into account lines 2c through 3. Recordkeeping You must keep records to support items Future Developments Purpose of Form reported on Form 6251 in case the IRS For the latest information about Use Form 6251 to figure the amount, if has questions about them. If the IRS developments related to Form 6251 and any, of your alternative minimum tax examines your tax return, you may be its instructions, such as legislation (AMT). The AMT is a separate tax that asked to explain the items reported. enacted after they were published, go to is imposed in addition to your regular Good records will help you explain any IRS.gov/Form6251. tax. It applies to taxpayers who have item and arrive at the correct AMT. certain types of income that receive Keep records that show how you favorable treatment, or who qualify for What's New figured income, deductions, etc., for the certain deductions, under the tax law. -

![[REG-107100-00] RIN 1545-AY26 Disallowance of De](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2433/reg-107100-00-rin-1545-ay26-disallowance-of-de-1222433.webp)

[REG-107100-00] RIN 1545-AY26 Disallowance of De

[4830-01-p] DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Internal Revenue Service 26 CFR Part 1 [REG-107100-00] RIN 1545-AY26 Disallowance of Deductions and Credits for Failure to File Timely Return AGENCY: Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Treasury. ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking by cross-reference to temporary regulations and notice of public hearing. SUMMARY: This document contains proposed regulations relating to the disallowance of deductions and credits for nonresident alien individuals and foreign corporations that fail to file a timely U.S. income tax return. The current regulations permit nonresident aliens and foreign corporations the benefit of deductions and credits only if they timely file a U.S. income tax return in accordance with subtitle F of the Internal Revenue Code, unless the Commissioner waives the filing deadlines. The temporary regulations revise the waiver standard. The text of the temporary regulations on this subject in this issue of the Federal Register also serves as the text of these proposed regulations set forth in this cross-referenced notice of proposed rulemaking. This document also provides notice of a public hearing on these proposed regulations. DATES: Written comments must be received by April 29, 2002. Requests to speak and outlines of topics to be discussed at the public hearing scheduled for June 3, 2002, at 10 a.m. must be received by May 13, 2002. ADDRESSES: Send submissions to: CC:ITA:RU (REG-107100-00), room 5226, Internal -2- Revenue Service, POB 7604, Ben Franklin Station, Washington, DC 20044. Submissions may be hand delivered Monday through Friday between the hours of 8 a.m. -

Taxation and the Bankruptcy Code

Chapter 4: Other Recommendations and Issues TAXATION AND THE BANKRUPTCY CODE COMMENTS PREPARED BY PROFESSOR JACK WILLIAMS RECOMMENDATIONS 4.2.1 Clarify provisions of the Bankruptcy Code on providing reasonable notice to governmental units. 4.2.2 Amend the Bankruptcy Code to prescribe that to the extent that a tax claim presently is entitled to interest, such interest shall accrue at a stated statutory rate. 4.2.3 The Commission should submit to the Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules of the Judicial Conference (“Rules Committee”) a recommendation that the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure require that notices demanding the benefits of rapid examination under 11 U.S.C. § 505(b) be sent to the office specifically designated by the applicable taxing authority for such purpose, in any reasonable manner prescribed by such taxing authority. 4.2.4 Conform § 346 of the Bankruptcy Code to IRC 1398(d)(2) election; also conform local and state tax attributes that are transferred to the estate to those tax attributes that are transferred to the bankruptcy estate under IRC § 1398. 4.2.5 Amend 11 U.S.C. § 507(a)(8) and 523(a)(1) to provide for the tolling of relevant periods in the case of successive filings. Thus, in the event of successive bankruptcy filings, the time periods specified in § 507(a)(8) shall be suspended during the period in which a governmental unit was prohibited from pursuing a claim by reason of the prior case. 945 Bankruptcy: The Next Twenty Years 4.2.6 Amend 11 U.S.C. § 507(a)(8)(ii) to toll the 240-day assessment period for both pre- and post assessment offers in compromise.