History Subcommittee Report March 9, 2021 Councilmember Hildy S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Am Submitting

Citizens Redistricting Commission 901 P Street, Suite 154-A Sacramento, CA 95814 June 28, 2011 Dear Commission: I am submitting this written comment requesting that the California Citizens Redistricting Commission [hereinafter cited as Commission] modify its first draft for the State Senate Districts located within certain counties subject to the Section 5 preclearance requirement of the federal Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c (Monterey, Kings and Merced) and adjoining counties.1 At issue are the areas included within current Senate District 12, 15 and 16. The proposed Senate Districts may not meet the Section 5 and Section 2, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, standards of the federal Voting Rights Act. Under Section 5, a covered jurisdiction has the statutory duty to submit all changes affecting voting, including redistricting plans,2 and secure approval from the federal government. There are two procedures available to secure this approval. The submitting jurisdiction has the choice of pursuing one or the other and can also pursue both simultaneously. Under the first procedure, the covered jurisdiction can submit the proposed voting change to the United States Attorney General for approval or administrative preclearance. Under the second procedure, the covered jurisdiction can file an action in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia seeking judicial preclearance. Under either procedure, the submitting jurisdiction has the statutory duty to demonstrate that the proposed change affecting voting does not have a discriminatory effect on minority voting strength and was not adopted pursuant to a discriminatory intent. With respect to the discriminatory effect prong of Section 5, the covered jurisdiction must prove that the proposed voting change does not result in a retrogression, or a worsening, of minority voting strength. -

The Year 1960

mike davis THE YEAR 1960 dward thompson famously characterized the 1950s as the ‘apathetic decade’ when people ‘looked to private solutions to public evils’. ‘Private ambitions’, he wrote, ‘have displaced social aspirations. And people have come to feel their griev- Eances as personal to themselves, and, similarly, the grievances of other people are felt to be the affair of other people. If a connection between the two is made, people tend to feel—in the prevailing apathy—that they are impotent to effect any change.’1 The year 1960 will always be remem- bered for the birth of a new social consciousness that repudiated this culture of moral apathy fed by resigned powerlessness. ‘Our political task’, wrote the veteran pacifist A. J. Muste at that time, ‘is precisely, in Martin Buber’s magnificent formulation, “to drive the ploughshare of the normative principle into the hard soil of political reality”.’ The method was direct action—nonviolent and determined. First behind the plough were Black students in the South, whose move- ment as it spread to a hundred cities and campuses would name itself the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (sncc). In North Carolina, the Greensboro lunch-counter February sit-ins began as quiet protests but soon became thunderclaps heralding the arrival of a new, uncom- promising generation on the frontline of the battle against segregation. The continuing eruption of student protest across the South reinvigor- ated the wounded movement led by Martin Luther King and was echoed in the North by picket lines, boycotts and the growth of the Congress of Racial Equality (core).2 Separately the Nation of Islam grew rapidly, and the powerful voice of Malcolm X began to be heard across the country. -

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2019-4766-HCM ENV-2019-4767-CE HEARING DATE: September 5, 2019 Location: 2421-2425 North Silver Ridge Avenue TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 13 – O’Farrell PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Silver Lake – Echo Park – 200 N. Spring Street Elysian Valley Los Angeles, CA 90012 Area Planning Commission: East Los Angeles Neighborhood Council: Silver Lake Legal Description: Tract 6599, Lots 15-16 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the HAWK HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property an Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Bryan Libit APPLICANT: 2421 Silver Ridge Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90039 PREPARER: Jenna Snow PO Box 5201 Sherman Oaks, CA 91413 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as an Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of PlanningN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Melissa Jones, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachment: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2019-4766-HCM 2421-2425 Silver Ridge Avenue Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The Hawk House is a two-story single-family residence and detached garage located on Silver Ridge Avenue in Silver Lake. Constructed in 1939, it was designed by architect Harwell Hamilton Harris (1903-1990) in the Early Modern architectural style for Edwin “Stan” Stanton and Ethyle Hawk. -

January 30, 1968 Staff Bulletin

Archives BUI.I.E 7alifornia State Polytechnic College Volume 18, Number 19 San Luis Obispo January STATE COLLEGE ANNUAL REPORT ON PERSONNEL AVAILABLE The fifth annual report to the governor and the legislature on personnel matters in the California State Colleges has been distributed by the Office of the Chancellor. On this campus two copies have been received for the Academic Subcouncil of the Faculty-Staff Council and two for the .Staff Subcouncil. Two copies have been sent to the library, one for the Faculty Reading Room and the other for general circula tion. The report is in three parts which deal respectively with academic personnel, per sonnel programs for support staffs, and program augmentation and policies requiring approval or funding beyond the immediate authority of the board. PLANS FOR ANNUAL CAMPUS BLOOD BANK DRAWING LISTED Members of the campus community interested in participating in the annual campus Blood Bank Drawing, being planned for February 9, have been invited to contact the Health Center to make appointments by College Physician Billy Mounts. The 1968 drawing is being sponsored by the student Applied Arts Council and will benefit the Cal Poly Fund in the Tri-Counties Blood Bank. The Cal Poly Fund is ·for the benefit of any member of the Cal Poly family, including members of the student body, staff, and faculty, and their families. Dr. Mounts said that those planning to donate during the drawing should abstain from food for four hours beforehand, be in good health, and not be. taking medication. DATES FOR CAMPUS OBSERVANCE OF ''NATIONAL ENGINEERS WEEK" LISTED More than 1,300 students of the School of Engineering will observe National Engineer6 Week February 19-25. -

Itet Vor (A, • 13MS Nay& If Ear

tt10 I1t=a1 z:creT,ary General Conference SDA TAVOM A Pi,4r/ WASHL C itet vor (A, • 13MS Nay& if ear VOL. 46 ANGWIN, CALIFORNIA, MARCH 5, 1947 NO. 30 Youth Evangelism Plans young people in all our churches and lation was just one-third of its present HEAR YE! GIVE EAR! schools of all levels. status. Good news indeed! "3. Encouraging our workers to As a soul-winning auxiliary of the In one week, 3,277 young people visit and pray, if possible, in every home first magnitude for 1947 Signs presents were baptized and joined baptismal where there are children and youth. an unusual array of article content from classes. The M.V. Week of Prayer last "4. Organizing baptismal classes and well-known contributors in our great year produced these splendid results. conducting baptisms of properly quali- organization. And all of this with only 30 per cent of fied young people, who have accepted Our people will be happy to know our churches holding evangelistic meet- Christ as their Saviour, and who are that the circulation achievement men- ings for youth. What good might have determined by God's grace to follow tioned above places Signs in a leading been done if all our churches had put Him." role among Protestant weeklies in the forth comparable efforts? E. W. DUNBAR, Secretary United States. The Christian Advooate Now we face another such oppor- Young People's Department of is second, with a circulation of approxi- tunity. March 8-15 is the spring Week Missionary Volunteers. mately 310,000 copies. -

June 2014 Special Edition

City Manager Newsletter By TRACKDOWN MANAGEMENT "Providing thread to help stitch together the fabric of the City Management Community" Special June, 2014 Page | 1 Volume No. 8, Issue No. 10 Patterson Volume No. 8, Issue No. 9 Gilroy City Managers with a Patterson Connection With our "connection" series, we have traveled from San Diego to Lakewood to Pismo Beach, and to Gilroy! From there we take Highway 152 over the Pacheco Pass, passing by the San Luis Reservoir to Interstate 5, and then north past Santa Nella to the City of Patterson. Patterson is in Stanislaus County, a little less than 30 miles south of Tracy. Patterson is part of the Modesto Metropolitan Statistical Area. It has an area of Veteran Lakewood City Manager 5.954 square miles and a population of a little Howard L. Chambers chatted with Julie Knabe, wife more than 20,000. The city is still known as the of Los Angeles County Supervisor Don Knabe, and California Contract Cities Association Executive "Apricot Capital of the World." Each year the Director Sam Olivito at the Wednesday, June 18, city holds an annual Apricot Fiesta. Patterson 2014 CCCA meeting hosted by the City of incorporated on December 22, 1919, to Lakewood at The Centre at Sycamore Plaza. become the 3rd city in Stanislaus County. / http / http http / http / http http http://www.ocsec.com/ / http://www.ocsec.com/ / / http.aspx Jack & Susan Simpson, 16707 Gerritt Avenue, Cerritos, CA 90703 O | 562/926-0800 M | 562/896-5424 M | 310/418-1035 www.trackdownmanagement.net | [email protected] | [email protected] City Manager Newsletter By Trackdown Management Page 2 Special June, 2014 Patterson City Managers with a Rolling Hills Estates City Manager Doug Prichard and La Puente City Manager David Carmany at a joint Patterson Connection meeting of the "contract cities" City Manager Committee and the City Managers of the Los Rod B. -

CALIFORNIO RESISTANCE to the US INVASION of 1846 a University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University

CALIFORNIO RESISTANCE TO THE U.S. INVASION OF 1846 A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, East Bay In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master in History By Patricia Campos Scheiner March,2009 CALIFORNIO RESISTANCE TO THE U.s. INVASION OF 1846 By Patricia Campos Scheiner Approved: Date: ~.~~~- 3 - / /- .L?c? q Dr. obert Phelps, Associate Professor 11 Table of Contents Page Chapter One. Introduction............ 1 Chapter Two. Californio Origins 14 Chapter Three. Californio's Politics... 30 Chapter Four. The Consequences of the Mexican-American War In California....................................... 46 Chapter Five. The "Unofficial" War in California: Fremont, the Provocateur, the Bear Flag Rebels' Actions, and the Battle of Olompali 51 Chapter Six. The "Official" War in California: The Battles of San Pedro, Natividad, San Pascual, San Gabriel and Mesa 62 Chapter Seven. The "Trojan Horse," and the "Fifth Columns" 88 Chapter Eight. Conclusion......... 101 Works Cited 110 iii 1 Chapter 1 Introduction In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner, one of the most influential American historians of the early 20th Century, argued that the core of American history could be found at its edges and that the American people, proceeding towards the West in their struggle with the wild frontier, had conquered free land. As such, United States' history was largely the study of Americans' westward advance, and became the supposed critical factor in their political and social development. In reference to -

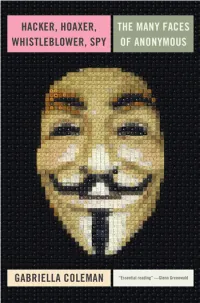

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2017 Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis Gregory I. Ruth Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sports Management Commons Recommended Citation Ruth, Gregory I., "Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis" (2017). Dissertations. 2848. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2848 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2017 Gregory I. Ruth LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PANCHO’S RACKET AND THE LONG ROAD TO PROFESSIONAL TENNIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY GREGORY ISAAC RUTH CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2017 Copyright by Gregory Isaac Ruth, 2017 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Three historians helped to make this study possible. Timothy Gilfoyle supervised my work with great skill. He gave me breathing room to research, write, and rewrite. When he finally received a completed draft, he turned that writing around with the speed and thoroughness of a seasoned editor. Tim’s own hunger for scholarship also served as a model for how a historian should act. I’ll always cherish the conversations we shared over Metropolis coffee— topics that ranged far and wide across historical subjects and contemporary happenings. -

STRUCTURE of MERIT ASSESSMENT REPORT 2102 5Th STREET #B, SANTA MONICA, CA

STRUCTURE OF MERIT ASSESSMENT REPORT 2102 5th STREET #B, SANTA MONICA, CA Prepared for: City of Santa Monica Planning & Community Development City Planning Division 1685 Main Street, Room 212 Santa Monica, CA 90401 Prepared by: Jan Ostashay Principal Ostashay & Associates Consulting PO BOX 542 Long Beach, CA 90801 SEPTEMBER 2016 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK STRUCTURE OF MERIT ASSESSMENT REPORT Rear Bungalow 2102 5th Street #B Santa Monica, CA 90405 APN: 4289‐010‐006 INTRODUCTION At the request of the City of Santa Monica Planning & Community Development Department (PCD), City Planning Division, Ostashay & Associates Consulting (OAC) has prepared this Structure of Merit Assessment Report for the property referred to as 2102 5th Street #B in the City of Santa Monica, California. This assessment report includes a discussion of the survey methodology used, a summarized description of the property, a brief description and contextual history of the property, evaluation of significance under the City of Santa Monica Structure of Merit criteria, photographs, and any applicable supporting materials. The parcel in which the subject property is located is developed with two residential improvements with 2102 5th Street #B sited at the rear half of lot. OAC documented and evaluated the subject property to determine whether it appears to satisfy one or more of the statutory criteria associated with City of Santa Monica Structure of Merit eligibility requirements, pursuant to Chapter 9.56 (Landmarks and Historic Districts Ordinance) of the Santa Monica Municipal Code. METHODOLOGY The assessment was conducted by Jan Ostashay, principal with OAC. In order to identify and evaluate the subject property as a potential Structure of Merit candidate, an intensive‐level survey was conducted. -

Northrop Grumman Corporation (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on July 17, 2002 Registration No. 333-83672 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 AMENDMENT NO. 4 TO FORM S-4 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 Northrop Grumman Corporation (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 3812 95-4840775 (State or other jurisdiction of (Primary Standard Industrial (I.R.S. Employee incorporation or organization) Classification Code Number) Identification Number) 1840 Century Park East Los Angeles, California 90067 (310) 553-6262 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant’s principal executive offices) John H. Mullan Corporate Vice President and Secretary 1840 Century Park East Los Angeles, California 90067 (310) 553-6262 (Name, address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of agent for service) Copies To: Andrew E. Bogen Peter Allan Atkins Peter F. Ziegler Eric L. Cochran Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP 333 South Grand Avenue Four Times Square Los Angeles, California 90071-3197 New York, New York 10036 (213) 229-7000 (212) 735-3000 Approximate date of commencement of proposed sale of the securities to the public: As soon as practicable after this registration statement becomes effective and upon completion of the transactions described in the enclosed prospectus. If the securities being registered on this Form are being offered in connection with the formation of a holding company and there is compliance with General Instruction G, check the following box. ☐ If this Form is filed to register additional securities for an offering pursuant to Rule 462(b) under the Securities Act, check the following box and list the Securities Act registration statement number of the earlier effective registration statement for the same offering. -

Sacramento Business Meeting Vol. 2 of 2

BEFORE THE CALIFORNIA CITIZENS REDISTRICTING COMMISSION In the matter of Full Commission Line-Drawing Meeting VOLUME II University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law Classroom C 3200 Fifth Avenue Sacramento, California Thursday, July 14, 2011 9:00 A.M. Reported by: Kent Odell CALIFORNIA REPORTING, LLC 167 52 Longwood Drive, San Rafael, CA 94901 (415) 457-4417 APPEARANCES Commissioners Present Angelo Ancheta, Chairperson Lilbert “Gil” Ontai, Vice-Chairperson Gabino Aguirre Vincent Barabba Maria Blanco Cynthia Dai Michelle DiGuilio Stanley Forbes Connie Galambos Malloy M. Andre Parvenu Jeanne Raya Michael Ward Jodie Filkins Webber Peter Yao Staff Present Dan Claypool, Executive Director Kirk Miller, Chief Legal Counsel Janeece Sargis, Administrative Assistant CALIFORNIA REPORTING, LLC 168 52 Longwood Drive, San Rafael, CA 94901 (415) 457-4417 APPEARANCES (CONT.) Consultants Present George Brown, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Karin MacDonald, Q2 Data & Research, LLC Alex Woods, Q2 Data & Research, LLC Nicole Boyle, Q2 Data & Research, LLC Also Present Public Comment Sam Spagnolo Rionne Jones Alex Vargas Sandra Jerabek Manuel Salazar Robert Huber Rachael O‟Brien Jim Provenza Diane Parro Don Saylor Steve Macias Scott Rabb Matt Williams Julio Gonzalez Leonard Lanzi Linda Lambourne Scott Stepanik CALIFORNIA REPORTING, LLC 169 52 Longwood Drive, San Rafael, CA 94901 (415) 457-4417 APPEARANCES (CONT.) Tim Watkins Erica Teasley-Linnock Four Waters Alice Huffman Nik Bonovich Michele Martinez Richard Seyman Debra Howard Hugh Bower CALIFORNIA REPORTING, LLC 170 52 Longwood Drive, San Rafael, CA 94901 (415) 457-4417 I N D E X Page Introduction Public Comment Voting Rights Act Counsel - Question & Answer Session Technical/Outreach Discussion topics 1.