FINLAND 01 En

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Governance Statement 2019

Governance 2019 1 Corporate Governance Statement 2019 Fortum Corporation (FORTUM) has been listed on Nasdaq Helsinki Committee and the Nomination and Remuneration Committee, and the the decision making on economic, environmental and social matters. since 18 December 1998. Fortum’s industrial sector, according to the President and CEO, supported by the Fortum Executive Management. The Audit and Risk Committee, members of the Fortum Executive Global Industry Classification Standard, is Electric Utilities. The State of Further, Fortum has an informal Advisory Council consisting of Management, and other senior executives support the Board of Directors Finland is the majority owner in Fortum with 50.76% of the shares as of representatives of Fortum’s stakeholder groups as invited by the Board of in the decision-making in these matters, when necessary. 31 December 2019. Directors. The Advisory Council aims at advancing Fortum’s businesses Corporate governance at Fortum is based on Finnish laws and the by facilitating a dialogue and exchange of views between Fortum and its General Meeting of Shareholders company’s Articles of Association. Fortum has fully complied with the stakeholders. In 2019, the Advisory Council consisted of 13 representatives The General Meeting of Shareholders is the highest decision-making Finnish Corporate Governance Code 2015 and fully complies with the new of Fortum’s stakeholder groups including three employee representatives. body of Fortum. Every shareholder has the right to attend the General Finnish Corporate Governance Code 2020, which the Securities Market As sustainability is an integral part of Fortum’s strategy and Meeting, propose items to be included on the agenda of the General Association adopted on 19 September 2019 and entered into force operations, the highest decision making on sustainability and climate- Meeting and exercise his/her power of decision in the matters belonging on 1 January 2020. -

Creating the Technology to Connect the World

Nokia Annual Report on Form 20-F 2019 on Form Nokia Annual Report Creating the technology to connect the world Nokia Annual Report on Form 20-F 2019 As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 5, 2020 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 Commission file number 1-13202 Nokia Corporation (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter)) Republic of Finland (Jurisdiction of incorporation) Karaportti 3 FI-02610 Espoo, Finland (Address of principal executive offices) Esa Niinimäki, Deputy Chief Legal Officer, Corporate, Telephone: +358 (0) 10 44 88 000, Facsimile: +358 (0) 10 44 81 002, Karakaari 7, FI 02610 Espoo, Finland (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”): Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares NOK New York Stock Exchange Shares New York Stock Exchange(1) (1) Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares representing these shares, pursuant to the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Exchange Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the registrant’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

Wärtsilä Corporation Annual Report 2013 WÄRTSILÄ CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2013

Wärtsilä Corporation Annual report 2013 WÄRTSILÄ CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Table of contents 03 BUSINESS 37 SUSTAINABILITY 125 GOVERNANCE 170 INVESTORS 183 BOARD OF DIRECTORS' REPORT 200 FINANCIALS 2 WÄRTSILÄ CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2013 BUSINESS 03 BUSINESS 18 SHIP POWER 21 Operating environment 04 MESSAGE TO THE 25 Strategy SHAREHOLDERS 26 Ship Power and sustainability 06 THIS IS WÄRTSILÄ 28 Development 2013 07 Operating environment 29 SERVICES 07 Corporate strategy 31 Operating environment 09 Financial targets 32 Strategy 10 POWER PLANTS 33 Services and sustainability 12 Operating environment 34 Development 2013 15 Strategy 35 POWERTECH 16 Power Plants and sustainability 17 Development 2013 3 WÄRTSILÄ CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2013 BUSINESS Message to the shareholders Dear shareholders, For Wärtsilä, 2013 was a year of varying activity within our different end markets. While the improvement in global vessel contracting was significant, power generation markets declined for the second consecutive year. Unfavourable exchange rates and some delayed deliveries at the end of the year led to a slightly weaker than expected net sales development. Profitability on the other hand developed well, reaching 11.2% for the full year. I am pleased with the resilience we have shown in reaching our profitability targets, despite the lower level of sales. Cash flow from operating activities development was strong, increasing to EUR 578 million during the year. Global economic policies and fluctuations in emerging market currencies delayed customer decision-making in the power generation markets. Our Power Plants order intake developed accordingly, decreasing by 15%. 82% of the orders received were for gas based power plants, showing that there is continued demand for our fuel flexible solutions. -

View Annual Report

REPORT ANNUAL Konecranes Annual report 2010 www.konecranes.com lifting Businesses™ Corporate Headquarters Konecranes Plc P.O. Box 661 (Koneenkatu 8) FI-05801 Hyvinkää, Finland Tel +358 20 427 11 Fax +358 20 427 2099 Konecranes is an industry shaping, global group of dynamic Lifting Businesses™. Global Business Area Headquarters We have a strong commitment to provide our customers with products Service Equipment Konecranes Service Corporation Konecranes Finland Corporation and services of unrivalled quality, safety and reliability, which results in P.O. Box 135 (Koneenkatu 8) P.O. Box 662 (Koneenkatu 8) improved efficiency and performance of our customers’ businesses. FI-05801 Hyvinkää, Finland FI-05801 Hyvinkää, Finland Tel +358 20 427 11 Tel +358 20 427 11 Fax +358 20 427 4099 Fax +358 20 427 3009 Through applying both our unique knowledge and technology, and responsive service attitude of never letting the customer down, we are able to develop innovative and integrated lifting solutions that our Regional Headquarters customers can trust. Americas Nordic, Eastern Europe and India Konecranes, Inc. Konecranes Region NEI These solutions help increase customers’ productivity and profitability, 4401 Gateway Blvd. P.O. Box 662 (Koneenkatu 8) Springfield, OH 45502, USA FI-05801 Hyvinkää, Finland thus showing that we are not just lifting things, but entire businesses. Tel +1 937 525 5533 Tel +358 20 427 11 Fax +1 937 325 8945 Fax +358 20 427 3009 Western Europe, Middle East and Africa Asia-Pacific Konecranes Region WEMEA Konecranes (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. P.O. Box 662 (Koneenkatu 8) No. 789 Suide Road FI-05801 Hyvinkää, Finland Putuo District Tel +358 20 427 11 Shanghai, 200331, China Fax +358 20 427 2299 Tel +86 21 6662 9999 Fax +86 21 6363 6145 Corporate responsibility For corporate responsibility matters please contact [email protected] This publication is for general informational purposes only. -

Fortum Corporate Governance Statement 2020

Governance 2020 1 Corporate Governance Statement 2020 Fortum Corporation (Fortum) has been listed on Nasdaq Helsinki Fortum and its stakeholders. In 2020, the Advisory Council consisted General Meeting of Shareholders since 18 December 1998. Fortum’s industrial sector, according to the of 13 representatives of Fortum’s stakeholder groups including three The General Meeting of Shareholders is the highest decision-making Global Industry Classification Standard, is Electric Utilities. The State of employee representatives. body of Fortum. Every shareholder has the right to participate in the Finland is the majority owner in Fortum with 50.76% of the shares as on As sustainability is an integral part of Fortum’s strategy and General Meeting, propose items to be included on the agenda of the 31 December 2020. operations, the highest decision making on sustainability and climate- General Meeting and exercise his/her power of decision in the matters Corporate governance at Fortum is based on Finnish laws and the related matters falls on the duties of the members of the Board of belonging to the General Meeting by law, as stipulated in the Finnish company’s Articles of Association. Fortum fully complies with the Directors, who share joint responsibility for these matters. Therefore, Companies Act. Each share entitles to one vote. A shareholder also has Finnish Corporate Governance Code 2020. The corporate governance Fortum has not established a specific Sustainability Committee for the right to ask questions about the matters discussed at the General statement is issued separately from the operating and financial review, the decision making on economic, environmental and social matters. -

Proposed Members for the Board of Directors 2013 Henrik Ehrnrooth

1 (7) Proposed members for the Board of Directors 2013 Chairman Henrik Ehrnrooth born 1954, M.Sc. (Forest economics), B.Sc. (Econ.), Chairman of the Board of Directors of Pöyry Plc. Chairman of the Board of Directors 2009-. Chairman of the Personnel Committee 2009-. Chairman of the Working Committee 2011-. Member of the Board 2009-. Independent of the company, but not independent of the company’s significant shareholders. Henrik Ehrnrooth holds indirectly with his brothers Georg Ehrnrooth and Carl-Gustaf Ehrnrooth a controlling interest in Structor S.A., which is the largest shareholder of YIT Corporation. Primary working experience: Pöyry Plc: President and CEO 1986í1997, Economist 1979í1981. Positions of trust: Pöyry Plc: Chairman of the Board of Directors 2003-. Otava Ltd: Member of the Board of Directors 1988-. 2 (7) Vice Chairman Reino Hanhinen born 1943, M.Sc. (Eng.), D.Sc. (Tech.) h.c. Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors 2010-. Member of the Personnel Committee 2008-. Member of the Audit Committee 2006í2009 and 2012- Member of the Working Committee 2011-. Chairman of the Board 1989í2000 and 2006í2008. Member of the Board 1988-. Independent of YIT Corporation and its major shareholders. Primary working experience: YIT Corporation: Managing Director 2000-2005, President and CEO 1987-2005. Perusyhtymä Oy: Managing Director 1986-1987. YIT Oy Yleinen Insinööritoimisto: Managing Director 1985-1986. Oy PPTH-Norden Ab: Managing Director 1976-1985. YIT Oy Yleinen Insinööritoimisto: Division Manager 1974-1976, Work Supervisor 1968-1974 3 (7) Member Kim Gran born 1954, B.Sc. (Econ.), President and CEO of Nokian Tyres plc. Member of the Board of Directors 2008-. -

Corporate Governance Statement 2020

Corporate governance statement This corporate governance statement is prepared in Corporate accordance with Chapter 7, Section 7 of the Finnish Securities Markets Act (2012/746, as amended) and the Finnish governance Corporate Governance Code 2020 (the “Finnish Corporate Governance Code”). statement Introduction In 2020, we continued delivering on Nokia’s commitment to strong corporate governance and related practices. To do that, the Board activities are structured to develop the company’s strategy and to enable the Board to support the management on the delivery of it within a transparent governance framework. The table below sets out a high-level overview of the key areas of focus for the Board’s and its Committees’ activities during the year in addition to regular business and financial updates at each Board meeting and several reviews of the impacts and actions relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. January February/March April May July September/October December Board – Digitalization update – CEO change – Transformation update – Technology Strategy update – Annual sustainability review – Annual strategy meeting – Annual plan and long-range plan – Ethics & compliance and litigation – Postponing 2020 AGM due to – Convening the remote AGM – Digitalization update – Key market strategies – New operating model planning – Enterprise Risk Management update COVID-19 – Appointment of the new – Business group strategy planning – Board evaluation – Remuneration Policy to be Board Chair presented to the AGM – Nokia Equity Program 2020 Corporate -

Proposed Composition for Yit Corporation's Board Of

1(4) PROPOSED COMPOSITION FOR YIT CORPORATION’S BOARD OF DIRECTORS As Chairman Henrik Ehrnrooth, born 1954, M.Sc. (Forest economics), B.Sc. (Econ.), Chairman of the Board of Directors of Pöyry PLC Member of YIT’s Nomination and Rewards Committee since 2008. Not previously in YIT Corporation’s Board of Directors. Other positions of trust: Pöyry Plc Chairman of the Board of Directors 2003–, Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors 1997–2002, member of the Board of Directors 1997– Cargotec Corporation Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors 2005– Oy Forcit Ab member of the Board of Directors 2003– Otava Books and Magazines Group Ltd member of the Board of Directors 1988– Primary working experience: Pöyry Plc Chief Executive Officer 1995–1997 Pöyry Plc President and CEO 1986–1995 Pöyry Plc 1979– As Vice Chairman Eino Halonen, born 1949, M.Sc. (Econ.) Member of YIT’s Board of Directors since 2000 and Vice Chairman since 2003. Member of the Audit Committee since 2004 and the Nomination and Rewards Committee since 2008. Other positions of trust: Metsäliitto Osuuskunta member of the Board of Directors 2006– Cramo Oyj member of the Board of Directors 2003– Pohjola Bank member of the Board of Directors 2003– Primary working experience: Suomi Mutual Life Assurance Company Managing Director 2000– Pohjola Life Assurance Company Ltd Managing Director 1998–1999, Merita Nordbanken Executive Vice President, Regional Bank Manager 1998 Merita Bank Ltd Director and member of the Management Board 1996–1997 Kansallis-Osake-Pankki 1971–1995 2(4) As members Kim Gran, born 1954, B.Sc. -

FORTUM OYJ (Incorporated with Limited Liability in Finland)

BASE PROSPECTUS FORTUM OYJ (incorporated with limited liability in Finland) €8,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme Application has been made to the Luxembourg Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the "CSSF"), which is the Luxembourg competent authority for the purpose of Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (which includes the amendments made by Directive 2010/73/EU (the "2010 PD Amending Directive") to the extent that such amendments have been implemented in a relevant Member State of the European Economic Area) (the "Prospectus Directive") and relevant implementing measures in Luxembourg, to approve this document as a base prospectus issued in compliance with the Prospectus Directive and relevant implementing measures in Luxembourg for the purpose of giving information with regard to the issue of notes in bearer and/or registered form (respectively, "Bearer Notes" and "Registered Notes" and together the "Notes") issued under this €8,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the "Programme") described in this Base Prospectus during the period of twelve months after the date hereof. Pursuant to Article 7(7) of the Luxembourg law dated 10 July 2005 on prospectuses for securities (as amended), by approving this Base Prospectus, the CSSF assumes no responsibility as to the economic and financial soundness of the transactions contemplated under this Base Prospectus or the quality or the solvency of the Issuer. Application has been made for Notes issued under the Programme to be admitted to listing on the official list and to trading on the Regulated Market of the Luxembourg Stock Exchange. The Luxembourg Stock Exchange's Regulated Market is a regulated market for the purposes of the Market and Financial Instruments Directive 2004/39/EC. -

Neste Annual Report 2019 | Content 2 2019 in Brief

Faster, bolder and together Annual Report 2019 Content 02 03 2019 in brief ................................... 3 Sustainability ............................... 20 Governance ................................. 71 CEO’s review .................................. 4 Sustainability highlights ....................... 21 Corporate Governance Statement 2019 ........ 72 Managing sustainability ....................... 22 Risk management............................. 89 Neste creates value ......................... 25 Neste Remuneration Statement 2019 ........... 93 Neste as a part of society ................... 26 01 Stakeholder engagement ...................... 27 Strategy ..................................... 7 Sustainability KPIs ............................ 31 Our climate impact ............................ 33 04 Innovation .................................... 10 Our businesses ............................... 11 Renewable and recycled raw materials ......... 38 Review by the Board of Directors ......... 105 Key events 2019 .............................. 14 Supplier engagement ......................... 45 Key figures .................................. 123 Key figures 2019 .............................. 16 Environmental management ................... 48 Calculation of key figures ..................... 125 Financial targets .............................. 17 Our people ................................... 52 Information for investors....................... 18 Human rights ............................... 52 Employees and employment ................ -

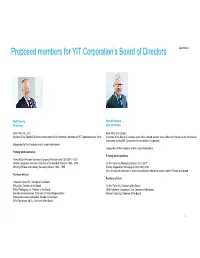

Appendix 1 Proposed Members for the Board of Directors

Proposed members for YIT Corporation’s Board of Directors Appendix 1 Matti Vuoria Berndt Brunow Chairman Vice Chairman born 1951, BA, LL.M. Born 1950, B.Sc.(Econ.) Member of the Board of Directors and member of the Personnel Committee of YIT Corporation since 2016. Chairman of the Board of Directors since 2008, a board member since 2002 and Chairman of the Nomination Committee and the HR Committee of Lemminkäinen Corporation. Independent of the Company and its major shareholders Independent of the Company and its major shareholders. Primary work experience Primary work experience Varma Mutual Pension Insurance Company, President and CEO 2004 – 2013 Fortum Corporation, Full-time Chairman of the Board of Directors 1998 – 2003 Oy Karl Fazer Ab, Managing Director 2002–2007 Ministry of Trade and Industry, Secretary General 1992 – 1998 Sanitec Corporation, Managing Director 2000–2002 Over 20 years of experience in executive positions in the forest industry both in Finland and abroad Positions of trust Positions of trust Cleantech Invest Plc., Member of the Board Wihuri Ltd., Member of the Board Oy Karl Fazer Ab, Chairman of the Board Wihuri Packaging Ltd., Member of the Board UPM Kymmene Corporation, Vice Chairman of the Board Svenska Handelsbanken, Chairman of Finland Regional Bank Hartwall Capital Ltd, Member of the Board Maanpuolustuksen aloitesäätiö, Member of the Board Mills Enterprises Ltd Oy, Chairman of the Board 1 Proposed members for YIT Corporation’s Board of Directors Erkki Järvinen Inka Mero Tiina Tuomela Member Member Member Born 1966, MSc (Eng), MBA, Executive Vice President in Fortum, Generation born 1960, M.Sc. (Econ.), President and CEO of Tikkurila Group born 1976, Master of Economics, Co-Founder and Division since 2016 and Member of the Management Team since 2014 2009 − Chairwoman, Pivot5 Oy Member of the Board of Directors and member of the Audit Committee of YIT Member of the Board of Directors since 2013 and Chairman of Member of the Board of Directors and member of the Personnel Corporation since 2017. -

Sustainability Reporting in 2020

Annual Report 2020 CHANGE RUNS ON RENEWABLES Content 2020 in brief 3 Sustainable supply chain 58 Governance 86 CEO’s review 4 Sustainability risk assessment Corporate Governance Statement 87 in our supply chain 59 Risk management 102 Strategy 7 Identifying our supply chains 59 Remuneration report 106 Innovation 9 Sustainability with our renewable Our businesses 10 raw material suppliers and oil suppliers 59 Review by the Key events 2020 13 Sustainability within indirect procurement 60 Board of Directors 112 Key figures 2020 15 Environment 62 Key figures 129 Financial targets 16 Environmental management 62 Calculation of key figures 131 Information for investors 17 Material and energy efficiency 63 Water in our own operations 63 Financial statements 134 19 Assessing the water-related risks 63 Sustainability Consolidated financial statements 135 Sustainability highlights 20 Continuous environmental quality monitoring 63 Parent company financial statements 195 Sustainability at Neste 21 Commitment to biodiversity 64 Proposal for the distribution of earnings Material sustainability topics 23 Environmental roadmap 65 and signing of the Review by the Board Stakeholder engagement 30 People 66 of Directors and the Financial Statements 212 Value creation 35 Employees and employment 66 Auditor’s Report 213 Sustainability governance and compliance 36 Human rights 68 Climate 38 Safety 71 Our climate impact 39 Performance and reporting 2020 76 Carbon neutral production by 2035 43 Performance in figures 77 Renewable raw materials 47 GRI Content Index and UN Global Compact 79 Recycled raw materials 54 Principles for calculating the key indicators 83 Independent Practitioner’s Assurance Report 84 Neste Annual Report 2020 | Content 2 Neste creates solutions for combating Revenue Leverage ratio climate change and accelerating a shift to a 11,751 MEUR -4.7% circular economy.