Sign in Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crítica De Cinema Na África

CINEMAS AFRICANOS CONTEMPORÂNEOS Abordagens Críticas SESC – SERVIÇO SOCIAL DO COMÉRCIO Administração Regional no Estado de São Paulo PRESIDENTE DO CONSELHO REGIONAL Abram Szajman DIRETOR DO DEPARTAMENTO REGIONAL Danilo Santos de Miranda SUPERINTENDENTES Técnico-Social Joel Naimayer Padula Comunicação Social Ivan Giannini Administração Luiz Deoclécio Massaro Galina Assessoria Técnica e de Planejamento Sérgio José Battistelli GERENTES Ação Cultural Rosana Paulo da Cunha Estudos e Desenvolvimento Marta Raquel Colabone Assessoria de Relações Internacionais Aurea Leszczynski Vieira Gonçalves Artes Gráficas Hélcio Magalhães Difusão e Promoção Marcos Ribeiro de Carvalho Digital Fernando Amodeo Tuacek CineSesc Gilson Packer CINE ÁFRICA 2020 Equipe Sesc Cecília de Nichile, Cesar Albornoz, Érica Georgino, Fernando Hugo da Cruz Fialho, Gabriella Rocha, Graziela Marcheti, Heloisa Pisani, Humberto Motta, João Cotrim, Karina Camargo Leal Musumeci, Kelly Adriano de Oliveira, Ricardo Tacioli, Rodrigo Gerace, Simone Yunes Curadoria e direção de produção e comunicação: Ana Camila Esteves Assistente de produção: Edmilia Barros Produção técnica: Daniel Petry Identidade visual, projeto gráfico e capa: Jéssica Patrícia Soares Assessoria de imprensa: Isidoro Guggiana Traduções e legendas: Casarini Produções Revisão: Ana Camila Esteves e Jusciele Oliveira CINEMAS AFRICANOS CONTEMPORÂNEOS Abordagens Críticas Ana Camila Esteves Jusciele Oliveira (Orgs.) São Paulo, Sesc 2020 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) C4909 Cinemas africanos contemporâneos: abordagens críticas / Ana Camila Esteves; Jusciele Oliveira (orgs.). – São Paulo: Sesc, 2020. – 1 ebook; xx Kb; e-PUB. il. – Bibliografia ISBN: 978-65-89239-00-0 1. Cinema africano. 2. Cine África. 3. Crítica. 4. Mostra de filmes. 5. Mostra virtual de filmes. 6. Publicações sobre cinema africano no Brasil e no mundo. I. Título. -

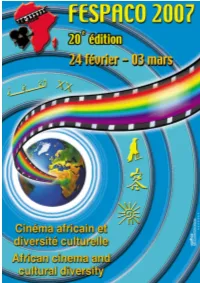

Catalogue2007.Pdf

Sommaire / Contents Comité National d'Organisation / The National Organising Committee 6 Mot du Ministre de la Culture des Arts et du Tourisme / Speech of the Minister of Culture, Arts and Tourism 7 Mot du président d'honneur / Speech of honorary chairperson 8 Mot du Président du Comité d'Organisation / Speech of the President of the Organising Committee 9 Mot du Président du Conseil d’Administration / / Speech of the President of Chaireperson of the Board of Adminsitration 11 Mot du Maire de la ville de Ouagadougou / Speech of the Mayor of the City of Ouagadougou 12 Mot du Délégué Général du Fespaco / Speech of the General Delegate of Fespaco 13 Regard sur Manu Dibango, président d'honneur du 20è festival / Focus on Manu Dibango, Chair of Honor 15 Film d'Ouverture / Opening film 19 Jury longs métrages / Feature film jury 22 Liste compétition longs métrages / Competing feature films 24 Compétition longs métrages / Feature film competition 25 Jury courts métrages et films documentaires / Short and documentary film jury 37 Liste compétition courts métrages / Competing short films 38 Compétition courts métrages / Short films competition 39 Liste compétition films documentaires / Competing documentary films 49 Compétition films documentaires / Documentary films competition 50 3 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 59 Panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 60 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique courts métrages / Panorama -

Collège Elémentaire Prescolaire

ELECTIONS DE REPRESENTATIVITE SYNDICALE DANS LE SECTEUR DE L'EDUCATION ET DE LA FORMATION COLLEGE ELEMENTAIRE PRESCOLAIRE IA DIOURBEL MATRICULE PRENOMS ENSEIGNANT NOM ENSEIGNANT DATE NAISS ENSEIGNANTLIEU NAISSANCE ENSEIGNANT SEXE CNI NOM ETABLISSEMENT IEF DEPT REGION 603651/G Ismaïla DJIGHALY 1975-09-14 00:00:00GOUDOMP M 1146199100521 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 683343/A CONSTANCE OLOU FAYE 1971-10-10 00:00:00FANDENE THEATHIE F 2631200300275 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 650740/B IBOU FAYE 1977-03-12 00:00:00NDONDOL M 1207198800622 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 689075/I DAOUDA GNING 1986-01-01 00:00:00BAMBEY SERERE M 1202199900024 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 161201019/A MAREME LEYE 1986-01-19 00:00:00MBACKE M 2225198600234 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 220021018/H ALIOU NDIAYE 1989-01-10 00:00:00MBARY M AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 120201103/Z BABACAR DIENG 1968-07-16 00:00:00TOUBA M 1238200601660 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130601117/B SOPHIE DIOP 1977-07-03 00:00:00Thiès F 2619197704684 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 642421/A Aboubacar Sadekh DIOUF 1979-06-02 00:00:00LAMBAYE M 1239199301074 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130201133/D ABDOU KHADRE D GUEYE 1974-04-11 00:00:00BAMBEY M 1191197400376 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130201063/H Assane KANE 1986-05-13 00:00:00BAMBEY M 1191199901066 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 635869/C MOUHAMADOU LAMINE BARA MBAYE 1981-10-20 00:00:00LAMBAYE M 1239199900506 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130201106/B -

Liste Lettre Commentaires Incomplete

LISTE LETTRE COMMENTAIRES INCOMPLETE N° NUMERO PRENOM NOM DATE NAISSANCELIEU NAISSANCE OBSERVATION 1 1 LC001009 Chérif Sidaty DIOP 22/05/1993 Dakar INCOMPLET 2 2 LC001024 Malick NIANE 25/06/1994 Gandiaye INCOMPLET 3 3 LC001029 FARMA FALL 16/08/1999 Parcelles Assainies U12 INCOMPLET 4 4 LC001039 Adama NDIAYE 13/04/1997 Saldé INCOMPLET 5 5 LC001060 Amadou DIA 23/10/1994 Thiaroye sur mer INCOMPLET 6 6 LC001070 Mouhamadou BARRY 24/08/1997 Dakar INCOMPLET 7 7 LC001090 Ibrahima KA 03/03/1996 Dahra INCOMPLET 8 8 LC001095 Ousseynou SENE 01/01/2000 Kaolack INCOMPLET 9 9 LC001099 Papa Masow TINE 27/05/2000 Gatte Gallo INCOMPLET 10 10 LC001105 NGAGNE FAYE 20/09/2000 Dakar INCOMPLET 11 11 LC001144 Adama SADIO 07/06/1996 Dakar INCOMPLET 12 12 LC001156 Arfang DIEDHIOU 05/04/1996 MLOMP INCOMPLET 13 13 LC001160 Modoulaye GNING 03/06/1994 Keur matouré e INCOMPLET 14 14 LC001175 Ablaye DABO 17/04/1998 Kaolack INCOMPLET 15 15 LC001176 Ibrahima KA 04/12/1999 Diamaguene Sicap Mbao INCOMPLET 16 16 LC001183 Mansour CISSE 11/03/1994 Rufisque INCOMPLET 17 17 LC001186 Ngouda BOB 14/01/1996 Ngothie INCOMPLET 18 18 LC001193 Abdoukhadre SENE 28/10/1999 Mbour INCOMPLET 19 19 LC001195 Jean paul NDIONE 07/04/1998 fandene ndiour INCOMPLET 20 20 LC001201 Abdou NDOUR 10/10/1996 Niodior INCOMPLET 21 21 LC001202 Yves Guillaume Djibosso DIEDHIOU 19/11/2020 Dakar INCOMPLET 22 22 LC001203 Mamour DRAME 06/10/1995 Guerane Goumack INCOMPLET 23 23 LC001207 Libasse MBAYE 10/07/1998 Dakar INCOMPLET 24 24 LC001211 Modou GUEYE 26/11/1999 Fordiokh INCOMPLET 25 25 LC001224 Bernard -

Banlieue Films Festival (BFF): Growing Cinephilia and Filmmaking in Senegal

Banlieue Films Festival (BFF): Growing cinephilia and filmmaking in Senegal Estrella Sendra SOAS, University of London and Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8344-2928 ABSTRACT This article examines small film festivals in the socio-cultural context of Senegal. Through the case study of the Banlieue Films Festival (BFF) in Dakar, founded in 2013 by Abdel Aziz Boye, I analyse the crucial role of festivals in strengthening the film industry, fostering cinephilia and encouraging the practical application of cultural policies. I suggest that contemporary film production, particularly, in the past five years (2015-2020) has been significantly shaped by grassroots initiatives that have eventually been transformed into structures. I also explore the role of “rooted cosmopolitans”, borrowing Kwame Appiah’s term in relation to the figure of Abdel Aziz Boye, who founded Cine UCAD at the Universite Cheikh Anta Diop, in Dakar, Cine Banlieue, and, upon returning to Senegal from France, the BFF. I discuss BFF’s various forms of legacy, concluding that it has been an active agent in forging a new cinephilia and inspiring a wave of young filmmakers in Senegal. KEYWORDS Banlieue Films Festival; Senegalese filmmaking; cinephilia; “rooted cosmopolitan”; film training; ethnography. Introduction Senegal enjoys an emblematic position in the history of African cinema. Following the increasing independence of African countries from French colonialism, Senegal became the home of pioneering filmmakers who would soon acquire international recognition, such as Ousmane Sembe ne (1923- 2007), Safi Faye (n. 1943), and Djibril Diop Mambe ty (1945-1998). These filmmakers sought to decolonise minds through the medium of film, and in doing so, to create a cinema from, by and for African people. -

Les Premiers Recensements Au Sénégal Et L'évolution Démographique

Les premiers recensements au Sénégal et l’évolution démographique Partie I : Présentation des documents Charles Becker et Victor Martin, CNRS Jean Schmitz et Monique Chastanet, ORSTOM Avec la collaboration de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, archivistes Ce document représente la mise en format électronique du document publié sous le même titre en 1983, qui est reproduit ici avec une pagination différente, mais en signa- lant les débuts des pages de la première version qui est à citer sour le titre : Charles Becker, Victor Martin, Jean Schmitz, Monique Chastanet, avec la collabora- tion de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, Les premiers recensements au Sé- négal et l’évolution démographique. Présentation de documents. Dakar, ORSTOM, 1983, 230 p. La présente version peut donc être citée soit selon la pagination de l’ouvrage originel, soit selon la pagination de cette version électronique, en mentionnant : Charles Becker, Victor Martin, Jean Schmitz, Monique Chastanet, avec la collabora- tion de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, Les premiers recensements au Sé- négal et l’évolution démographique. Présentation de documents. Dakar, 2008, 1 + 219 p. Dakar septembre 2008 Les premiers recensements au Sénégal et l’évolution démographique Partie I : Présentation des documents 1 Charles Becker et Victor Martin, CNRS Jean Schmitz et Monique Chastanet, ORSTOM Avec la collaboration de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, archivistes Kaolack - Dakar janvier 1983 1 La partie II (Commentaire des documents et étude sur l’évolution démographique) est en cours de préparation. Elle sera rédigée par les auteurs de cette première partie et par d’autres collaborateurs. Elle traitera surtout des données relatives aux effectifs de population et aux mouvements migratoires qui ont modifié profondément la configuration démographique du Sénégal depuis le milieu du 19ème siècle. -

Étude Sur Les Capacités Dans Le Secteur De La Nutrition Au Sénégal Gabriel Deussom N., Victoria Wise, Marie Solange Ndione, Aida Gadiaga

ANALYSE ET PERSPECTIVES : 15 ANNÉES D’EXPÉRIENCE DANS LE DÉVELOPPEMENT DE LA POLITIQUE NUTRITION AU SÉNÉGAL ANALYSE Étude sur les Capacités dans le Secteur de la Nutrition au Sénégal Gabriel Deussom N., Victoria Wise, Marie Solange Ndione, Aida Gadiaga Étude sur les Capacités dans le Secteur de la Nutrition au Sénégal Décembre 2018 Gabriel Deussom N., Victoria Wise, Marie Solange Ndione, Aida Gadiaga Analyse et Perspective : 15 Années d’Expérience dans le Développement de la Politique de Nutrition au Sénégal © 2018 Banque internationale pour la reconstruction et le développement / Banque mondiale 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Téléphone : 202–473–1000 Internet : www.worldbank.org Mention de la source : Le rapport doit être cité comme suit : Deussom, Gabriel N., Victoria Wise, Marie Solange Ndione, and Aida Gadiaga. 2018. « Étude sur les Capacités dans le Secteur de la Nutrition au Sénégal ». Analyse et Perspective : 15 Années d’Expérience dans le Développement de la Politique de Nutrition au Sénégal. License : Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO Ce rapport est produit par le personnel de la Banque mondiale avec des contributions externes. Les constats, interprétations et conclusions exprimées dans ce rapport ne reflètent pas nécessai- rement les vues de la Banque mondiale, de son Conseil d’administration ou des gouvernements qu’ils représentent. La Banque mondiale ne garantit pas l’exactitude des données figurant dans ce rapport. Les frontières, couleurs, dénominations et autres informations reprises dans les cartes géographiques qui l’illustrent n’impliquent aucun jugement de la part de la Banque mon- diale quant au statut légal d’un quelconque territoire, ni l’aval ou l’acceptation de ces frontières. -

African Studies Quarterly

African Studies Quarterly Volume 2, Issue 1 1998 Published by the Center for African Studies, University of Florida ISSN: 2152-2448 African Studies Quarterly Editorial Staff Nanette Barkey Michael Chege Maria Grosz-Ngate Parakh Hoon Carol Lauriault Peter Vondoepp Roos Willems African Studies Quarterly | Volume 2, Issue 1 | 1998 http://www.africa.ufl.edu/asq © University of Florida Board of Trustees, a public corporation of the State of Florida; permission is hereby granted for individuals to download articles for their own personal use. Published by the Center for African Studies, University of Florida. African Studies Quarterly | Volume 2, Issue 1 | 1998 http://www.africa.ufl.edu/asq Table of Contents Olodumare: God In Yoruba Belief And The Theistic Problem of Evil John A. I. Bewaji (1-17) Decentralization, Local Governance and The Democratic Transition in Southern Africa: A Comparative Analysis James S. Wunsch (19-45) At Issue: Reflections on African Cinema African Cinema In The Nineties Mbye Cham (47-51) Contemporary African Film at the 13th Annual Carter Lectures on Africa: Interviews with Filmmaker Salem Mekuria and Film Critic Sheila Petty Rebecca Gearhart (53-58) Book Reviews Development for Health: Selected ARTICLES from Development in Practice. Deborah Eade, ed. Published by Oxfam Publications (UK and Ireland), and Humanities Press International, 1997. Baffour Takyi (59-61) Encyclopedia of Pre-colonial Africa: Archeology, History, Languages, Culture, and Environments. Joseph O. Vogel, ed. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, A Division of Sage Publication, 1997. Jon Unruh (61-62) Sol Plaatje: Selected Writings. Brian Willan, ed. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1997. R. Hunt Davis (62-65) Physicians, Colonial Racism, and Diaspora in West Africa. -

Fighting the Greater Jihad New African Histories Series

Fighting the Greater Jihad new african histories series Series editors: Jean Allman and Allen Isaacman David William Cohen and E. S. Atieno Odhiambo, The Risks of Knowledge: Investigations into the Death of the Hon. Minister John Robert Ouko in Kenya, 1990 Belinda Bozzoli, Theatres of Struggle and the End of Apartheid Gary Kynoch, We Are Fighting the World: A History of Marashea Gangs in South Africa, 1947–1999 Stephanie Newell, The Forger’s Tale: The Search for Odeziaku Jacob A. Tropp, Natures of Colonial Change: Environmental Relations in the Making of the Transkei Jan Bender Shetler, Imagining Serengeti: A History of Landscape Memory in Tanzania from Earliest Times to the Present Cheikh Anta Babou, Fighting the Greater Jihad: Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya in Senegal, 1853–1913 Fighting the Greater Jihad Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853–1913 w Cheikh Anta Babou ohio university press athens Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701 www.ohio.edu/oupress © 2007 by Ohio University Press Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ƒ ™ 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 An earlier version of one section of chapter 4 appeared as “Educating the Murid: Theory and Practices of Education in Amadu Bamba’s Thought,” Journal of Reli- gion in Africa 33, no. 3 (2003): 310–27. An earlier version of chapter 7 appeared as “Contesting Space, Shaping Places: Making Room for the Muridiyya in Colonial Senegal, 1912–1945,” Journal of African History 46, no. -

Gender Terrains in African Cinema

Gender terrains in African cinema Dominica Dipio TERMS of USE The African Humanities Program has made this electronic version of the book available on the NISC website for free download to use in research or private study. It may not be re- posted on book or other digital repositories that allow systematic sharing or download. For any commercial or other uses please contact the publishers, NISC (Pty) Ltd. Print copies of this book and other titles in the African Humanities Series are available through the African Books Collective. © African Humanities Program Dedication To the affectionate memory of my father, Saturnino Bandhasi Okello, and my mother, Amelia Kalisa, who did not discriminate against their children and gave them the environment to dream. About the Series The African Humanities Series is a partnership between the African Humanities Program (AHP) of the American Council of Learned Societies and academic publishers NISC (Pty) Ltd*. The Series covers topics in African histories, languages, literatures, philosophies, politics and cultures. Submissions are solicited from Fellows of the AHP, which is administered by the American Council of Learned Societies and financially supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The purpose of the AHP is to encourage and enable the production of new knowledge by Africans in the five countries designated by the Carnegie Corporation: Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. AHP fellowships support one year’s work free from teaching and other responsibilities to allow the Fellow to complete the project proposed. Eligibility for the fellowship in the five countries is by domicile, not nationality. Book proposals are submitted to the AHP editorial board which manages the peer review process and selects manuscripts for publication by NISC. -

4 8 13 14 22 27 18 19

THE MASTER, THE REBEL, AND THE ARTIST: THE FILMS OF 4 OUSMANE SEMBÈNE, DJIBRIL DIOP MAMBÉTY, AND MOUSSA SENE ABSA FASHION IN FILM FESTIVAL: 8 BIRDS OF PARADISE ADRIFT IN AMERICA: 13 THE FILMS OF KELLY REICHARDT TALES FROM NEW 14 CHINESE CINEMA 18 SIGNAL TO NOISE 19 TERRENCE MALICK MILDRED PIERCE AND JEANNE DIELMAN: 23, Quai du 21 Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles FAMILY MATINEES: 22 SPRING TRAINING 25 BEHIND THE SCREEN 27 REAL VIRTUALITY 2 2 3 FILM PROGRAMS Friday, April 15 5:00 Salomé, introduced by All program times and dates are 7:00 Normal Love and Pat Kirkham (MI, p. 12) subject to change. Underground Opulence, 7:00 Fashions of 1934 introduced by Marketa (MI, p. 12) Key to theaters and screening rooms: Uhlirova (MI, p. 10) Monday & Tuesday, MI Moving Image Theater Saturday, April 16 April 25 & 26 BA Celeste and Armand Bartos Screening Room 12:30 Step into Liquid 2:30 Tron: Legacy in Dolby ML Media Lab (BA, p. 22) Digital 3-D (MI, p. 17) 2:00 Secrets of the Orient Wednesday, April 27 Friday, April 1 (MI, p. 10) 7:00 Writing In Treatment: A 7:00 An Evening with Kelly 5:00 Male and Female, Conversation with Yael Reichardt (MI, p. 13) introduced by Inga Fraser Hedaya (MI, p. 20) Saturday, April 2 (MI, p. 10) Friday, April 29 12:30 Boxing Gym (BA, p. 22) 7:00 The Devil Is A Woman 7:00 Thomas Mao and 21G 2:00 Xala, introduced by June and Inauguration of the (MI, p. 15) Givanni (MI, p. -

The Master, the Rebel, and the Artist: the Films of Ousmane Sembène, Djibril Diop Mambéty, and Moussa Sene Absa

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE MASTER, THE REBEL, AND THE ARTIST: THE FILMS OF OUSMANE SEMBÈNE, DJIBRIL DIOP MAMBÉTY, AND MOUSSA SENE ABSA Museum of the Moving Image and Institute of African Studies, Columbia University, present film series, personal appearances, and roundtable discussion April 2---10 The Senegalese filmmakers Ousmane Sembène (1923–2007) and Djibril Diop Mambéty (1945–1998) pioneered cinematic creativity in Africa. Among the many filmmakers they inspired is Moussa Sene Absa (b. 1958), a protégé and former assistant to Mambéty. Museum of the Moving Image and the Institute of African Studies, Columbia University, will collaborate to present a two-week series of film screenings, personal appearances, and discussions, including rare theatrical screenings of key films by the three filmmakers at the Museum, and a roundtable discussion at Columbia University. The film screenings, curated by June Givanni, will take place on weekends from April 2 through 10, 2011. All film screenings are included with Museum admission. The roundtable, organized by Mamadou Diouf, will take place at Columbia on Monday, April 4, which is Senegalese Independence Day. Among the highlights of the Museum film series are personal appearances by: Moussa Sene Absa, one of Senegal’s leading contemporary filmmakers, with his films Madame Brouette and Yoole: The Sacrifice ; Wasis Diop, brother of Djibril Diop Mambéty and a key collaborator on the film Hyenas , which will be screened along with Wasis Diop’s new short film Joe Oaukum ; Sada Niang, Mambéty’s biographer, introducing a screening of a newly restored 35mm print of Touki Bouki ; and Samba Gadjigo, Sembène’s biographer, presenting Sembène’s last feature film, Moolade.