Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francja Edit Nancy Thompson

‘Inspired by the Impressionists’ Provence Tour Art League of Ocean City June 14-24, 2020 with Nancy Ellen Thompson Experience Magical Provence A journey you will never forget! Join us! Lavender, vineyards, olive trees, thyme, fresh figs, medieval villages, markets and sun-filled landscapes! Discover why the region was such an inspiration for artists like Van Gogh, Picasso, Cezanne and Monet. Following in the footsteps of the Impressionists in Provence, we will visit many important and beautiful towns and villages: -St Remy where Vincent Van Gogh spent the last months of his life. We will visit Saint-Paul-de-Mausole monastery, the hospice where the painter produced some of his most famous works, such as the Sunflowers. -Aix-en-Provence, a thriving cultural center. Here we will visit Cézanne’s studio, left just as it was when he painted there. -Arles , a Provencal city called Little Rome. Centuries ago, it played an important role as a colony of Julius Caesar and today is a great museum of a city. This is the city where Vincent van Gogh created his most important paintings and lost his ear. Also, Picasso and his museum, to which Picasso, in love with Arles and in bullfights, donated a number of his works and thus initiated the creation of a museum of the art of his own name. June is lavender season! We will sketch beautiful fields and visit the lavender museum in Senanqe Abbey. It is one of the most photographic places in France. Of course, we make time to explore vineyards and have a wine tasting of French wines. -

Revisiting the Monument Fifty Years Since Panofsky’S Tomb Sculpture

REVISITING THE MONUMENT FIFTY YEARS SINCE PANOFSKY’S TOMB SCULPTURE EDITED BY ANN ADAMS JESSICA BARKER Revisiting The Monument: Fifty Years since Panofsky’s Tomb Sculpture Edited by Ann Adams and Jessica Barker With contributions by: Ann Adams Jessica Barker James Alexander Cameron Martha Dunkelman Shirin Fozi Sanne Frequin Robert Marcoux Susie Nash Geoffrey Nuttall Luca Palozzi Matthew Reeves Kim Woods Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2016, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-06-0 Courtauld Books Online Advisory Board: Paul Binski (University of Cambridge) Thomas Crow (Institute of Fine Arts) Michael Ann Holly (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. -

En Vaucluse, Avignon, Sur Les Chemins De Vos Vacances

En Vaucluse, Avignon, sur les chemins de vos vacances... Rejoignez l'Association des Amis de Saint-Hilaire ! ici Pour agrandir le document, cliquez ici Table des matières ici ► Le raccourci CTRL + F ici 1 Page Avignon, capitale de la Chrétienté au Moyen Âge En bleu clair : tracé hypothétique du Rhône pendant l'Antiquité. En noir : restitution de l'enceinte de l'Antiquité tardive. En violacé : emprise de l'enceinte médiévale. Office de Tourisme d'Avignon Adresse : 41, cours Jean Jaurès (plan) 84000 Avignon Tél. : +33 (0)4 32 74 32 74 Horaires : • lundi au samedi : 9h00-18h00 • dimanches et jours fériés : 10h00-17h00 ► Site Internet ici ► Plan d'Avignon (2014) ici 2 Page Se garer : l’offre en détail Pour agrandir ce document de 2016, cliquez ici Parkings gratuits ► L'île Piot (gratuit) plan • Tél. : 04 32 76 22 69 - 1.100 places surveillées (gardien) ; navettes gratuites toutes les 10 min, du parking jusqu'à la porte de l'Oulle (5 minutes à pied de la place de l'Horloge), lun/sam 7h30/20h30, sam dès 13h. ► Les Italiens (gratuit) plan • tél. : 04 32 76 24 57 - 1.600 places surveillées (gardien) ; navettes CityZen, gratuites, toutes les 5 min, arrêts centre-ville, 7h/20h 6j/7 ; 20 min lundi/jeudi 20h/22h30 et ven/sam 20h/00h, 30 min dim 8/19h (infos). 3 Page ► FabricA (uniquement pendant le festival, gratuit) plan • 11, rue Paul-Achard ; pas de tél. - 250 places surveillées (caméra) ; desservi gratuitement par les lignes de bus TCRA pour les automobilistes y ayant garé leurs véhicules. ► Maraîchers (uniquement pendant le festival, gratuit) plan • À hauteur du 135, avenue Pierre Senard (MIN) ; pas de tél. -

MEDICINE and RELIGION C.

OXFORD HISTORICAL MONOGRAPHS EDITORS R. R. DAVIES R. J. W. EVANS P. LANGFORD H. C. G. MATTHEW H. M. MAYR-HARTING A. J. NICHOLLS SIR KEITH THOMAS MEDICINE AND RELIGION c.1300 The Case of Arnau de Vilanova JOSEPH ZIEGLER CLARENDON PRESS · OXFORD 1998 Oxford University Press, Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford New Y ork Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New Y ork © Joseph Ziegler 1998 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First published 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms in other countries should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data applied for ISBN 0–19–820726–3 13579108642 Typeset by Cambrian Typesetters, Frimley, Surrey Printed in Great Britain by Bookcraft Ltd., Midsomer-Norton Nr. -

Maison D'estavayé

Suisse (Pays de Vaud, Fribourg) Rives du lac de Neuchâtel (alias d’Yverdons) ; Estavayer, Chenaux (commune de Cully), Gorgier, Font, Saint-Martin- Maison d’Estavayé du-Chêne, Rueyres-les-Prés, Villargiroud, Molondin, Montet (Broye), Lully, Cugy. Branches de Font, Montagny & Gorgier (Fribourg) (alias Estavayer) En France, notamment à Sens ; maintenue en noblesse en 1668 Armes : «Palé d’or & de gueules de six pièces, à une fasce Estavayé d’argent chargée de trois roses de gueules brochant sur le tout» Au XV° siècle les armes sont : «une rose de gueules dans un champ d'argent». L'écu est surmonté d'un heaume ouvert de front. Lambrequins d'or, d'argent & de gueules. Devise : «Noblesse d'Estavayé». Supports : deux lion rampants d'or. Sources complémentaires : Estavayé-Font Estavayé-Montagny Estavayé-Gorgier Dictionnaire de la Noblesse (F. A. Aubert de La Chesnaye- Desbois, éd. 1775, Héraldique & Généalogie), "Grand Armorial de France" - Henri Jougla de Morenas & Raoul de Warren - Reprint Mémoires & Documents - 1948, Généanet, Contribution de Giles Tournier (d’Affry) (11/2014) à propos de Charlotte de Luxembourg et de sa descendance en Suisse, © 2019 Etienne Pattou «Catalogue des élèves de Juilly, 1651-1745», dernière mise à jour : 26/08/2019 Bulletin de l’Institut Fribourgeois d’Héraldique & de Génélogie sur http://racineshistoire.free.fr/LGN (IFHG) n°39 (11/2006) 1 Hugo d'Estavayé La Sarraz et Grandson, apparentés aux Estavayé, possédaient à leur origine les mêmes armes : seigneur d'Estavayé au XI°s. un palé de six pièces d’argent & d’azur, à la bande Estavayé ép. ? de gueules, chargées de trois coquilles ou étoiles d'or, le palé était parfois remplacé par un chef chargé La famille d’Estavayé (act. -

Revisiting the Monument Fifty Years Since Panofsky’S Tomb Sculpture

REVISITING THE MONUMENT FIFTY YEARS SINCE PANOFSKY’S TOMB SCULPTURE EDITED BY ANN ADAMS JESSICA BARKER Revisiting The Monument: Fifty Years since Panofsky’s Tomb Sculpture Edited by Ann Adams and Jessica Barker With contributions by: Ann Adams Jessica Barker James Alexander Cameron Martha Dunkelman Shirin Fozi Sanne Frequin Robert Marcoux Susie Nash Geoffrey Nuttall Luca Palozzi Matthew Reeves Kim Woods Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2016, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-06-0 Courtauld Books Online Advisory Board: Paul Binski (University of Cambridge) Thomas Crow (Institute of Fine Arts) Michael Ann Holly (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. -

Between Brothers: Brotherhood and Masculinity in the Later Middle Ages a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED to the FACULTY of the UNIVERSIT

Between Brothers: Brotherhood and Masculinity in the Later Middle Ages A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Cameron Wade Bradley IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ruth Mazo Karras July 2015 © Cameron Wade Bradley, 2015 Acknowledgements As with all serious labors, this study could not have been accomplished without considerable assistance from many quarters. My advisor, Ruth Karras, provided tireless support, encouragement, and invaluable guidance during the entire process. Through many meetings, responses to my late-night emails, and incisive comments on my work, she challenged me to think ever more deeply about my subject. Thank you for making me a better historian. I wish also to offer special thanks to Kathryn Reyerson, who enthusiastically fostered my professional development and gave perceptive and timely feedback on my dissertation. I am truly grateful for both their efforts as well as the suggestions given by the other members of my committee: Mary Franklin-Brown, Michael Lower, and Marguerite Ragnow. I would like to extend my thanks to Amy Livingstone, David Crouch, and Barbara Welke, who heard or read portions of this dissertation and offered helpful suggestions. To my fellow travelers Adam Blackler, Jesse Izzo, Basit Hammad Qureshi, Tiffany Vann Sprecher, Alexander Wisnoski, and Ann Zimo, I owe particular thanks. I am grateful for their enthusiasm, encouragement, and the unfailingly insightful critiques they offered on my work. Their fellowship, and the intellectual vibrancy of the wider community of scholars—medievalists and others—at the University of Minnesota made my graduate work there a rewarding experience. -

"Silence Visible"

*2* "SilenceVisible" Cartb usian D evotiorual Reading and Meditative Practice That frame of social being, which so long Had bodied forth the ghostliness of things In silence visible and perpetual calm. WI LLIAM \vORDSWORTII on the Grande Chartreuse, Tbe Prelude (r85o), YI.4z7-29 The Carthusianwilderness is no place to expect pageantry,whether visual or verbal. Even more than other monastic orders, medieval Carthusians eschewed devotional pomp and spectacle, only rarely coming together even in liturgical celebration. These monks were hermits in religious life, and each one lived out an austere and almost completely solitary existence in his individual cell. Yet surprisingly, the imaginative life of the Carthu- sians,as reflected in their private devotional texts and images, provides some of the community that their vows of solitude renounce, and even some of the pageant.rythat their ourward rites reject. Private devotional performances in the cell substituted for the sights and soundsof communal worship, and Carthusian performative reading in the Middle Ages often operated as a personal analogue to collective liturgical events.The monks' own metaphors show that they understood this compensatory function of their private activities; they understood reading and writing as communal pursuits, for instance, and created the textud sociery of the charterhouse explicitly to take the place of any bodily one. Moreover, visual images of severalkinds were used by Carthusians both for private purposes and for ostentatious display Carthusian devotional images and texts repeatedly represent communities both monastic and heavenly, constructing their solitary readersand viewers according to their place in those communities. Both books and art work to negotiate the complicated divide berween pri- va.teand public prayer in the charterhouse, a divide bridged by the paradox of private performances in late-medieval Carthusian reading. -

365 Belles Journées

Christian Laflamme réservés 365 belles journées d’adaptation avec Notre-Dame et de tous les saints traduction 700 citations de plus de 200 saints de et futurs saints Préface du Père Stéphane Roy reproduction, de droits Tous - PARVIS DU Editions du Parvis ÉDITIONS 1648 Hauteville / Suisse © réservés Dédicace d’adaptation et A Maman Marie, Notre-Dame de tous les saints traduction de reproduction, de droits Sincères remerciements Alain Gsell, Tous - Diane Laflamme, Julie Laflamme, et au Père Stéphane Roy PARVIS DU ÉDITIONS © DÉDICACE • 5 réservés Préface d’adaptation et «Oh! je voudrais chanter, MARIE, pourquoi je t’aime, traduction pourquoi ton nom, si doux, de fait tressaillir mon cœur.» Sainte Thérèse de l’Enfant-Jésus Poésie 54 reproduction, Pour le chrétien, disciple de Jésus-Christ, il suffit de de penser que notre Seigneur appela Marie «Maman» pour l’aimer à son tour et avoir confiance. En effet, c’est droits Elle sa mère, Elle qui nous le donna par un choix divin Tous devant lequel la foi et l’émerveillement nous entraînent - dans la longue procession de ceux qui la proclament bienheureuse. PARVIS Nombreux sont les noms et les titres par lesquels nous DU chantons les louanges de la Toute Sainte, Marie. Mais son appellation de «Mère de Dieu», «Theotokos», enferme en ÉDITIONS © PRÉFACE • 7 elle toutes les autres, comme les dogmes la concernant découlent de ce premier. Oui, ce nom contient tout le mystère de l’économie divine, et l’on comprend pourquoi les amis de Dieu aiment Marie et se disent ses enfants. réservés En Marie, l’âme contemplative se réjouit, se console, se développe et découvre un monde qui est bien celui de Dieu: Marie, mon devenir en Dieu. -

French Primitives." Manuscript Notes Circa 1927-1930 3.0 Folder(S)

The French Primitives and Their Forms from Their Origin to the End of the Fifteenth Century Manuscripts circa 1927–1931 FP Finding aid prepared by Adrienne Pruitt This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit June 13, 2017 Describing Archives: A Content Standard The Barnes Foundation Archives 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Philadelphia, PA 19130 Telephone: (215) 278-7280 Email: [email protected] Barnes Foundation Archives 2006 The French Primitives and Their Forms from Their Origin to the End of the Fifteenth Century Manuscri... Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Content.........................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... -

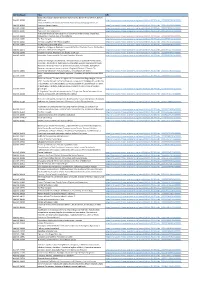

MS Shelfmark Title

MS Shelfmark Title URL Gaius Julius Caesar, Bellum Gallicum; Bellum Civile; Bellum Alexandrinum; Bellum Add MS 10084 Africanum https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100055964761.0x000001 Jonas of Orléans, De Institutione Laicali ; Epistola Concilii Aquisgranensis ad Add MS 10459 Pippinum Regem Directa https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100055965026.0x000001 Add MS 11283 Bestiary https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100055965341.0x000001 Add MS 11440 Two canon law compilations https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100059051170.0x000001 A versified chronicle from the priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs (imperfect), Add MS 11662 followed by a modern copy of the cartulary https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100055965720.0x000001 Add MS 11849 The Four Gospels https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100055966120.0x000001 Add MS 11850 The Four Gospels ('The Préaux Gospels') https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100055967262.0x000001 Add MS 11853 The Pauline Epistles with Gloss https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100060365082.0x000001 Augustine of Hippo, In Epistolam Joannis Ad Parthos Tractatus Decem, De Doctrina Add MS 11873 Christiana , Liber de vera religione https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/view3if/pl/ark:/81055/vdc_100059051570.0x000001 Add MS 11878 Gregory the Great, Moralia in Job (books 23-24:11) -

Biens Des Établissements Religieux Supprimés. Série S (Sauf Ordres De Saint-Lazare Et De Malte, Filles De La Charité Et Collège De La Sorbonne)

Biens des établissements religieux supprimés. Série S (sauf ordres de Saint-Lazare et de Malte, filles de la Charité et collège de la Sorbonne). Tome IX/A (XIIe-XVIIIe siècle) Répertoire général (S//6102-S//6154,S//6181-S//6210,S//6233-S/6748/2) Par H. Jassemin Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1927 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_003128 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé par l'entreprise diadeis dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence S//6102-S//6154,S//6181-S//6210,S//6233-S//6748/2 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Biens des établissements religieux supprimés. Série S (sauf ordres de Saint-Lazare et de Malte, filles de la Charité et collège de la Sorbonne). Tome IX/A Intitulé Inventaire général de la série S Intitulé Tome IX 1 ère partie Intitulé 6102-6748 Date(s) extrême(s) XIIe-XVIIIe siècle Localisation physique Paris DESCRIPTION Présentation du contenu Liste des fonds inventoriés dans ce volume. Hôpital de la charité p. 1 - Hôpital S te Catherine p.5 - Hôpital du S t Nom de Jésus; hôtel Dieu de S t Denis; hôpital de la Trinité, p. 10 - Hôpital S t Joseph de la Grave de Toulouse p. 11 - Hospitalières de S t Gervais p. 12 - Hospitalières de la Providence p.