Inflammatory Bowel Disease Agents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crohn's & Colitis Program, Patient Information Guide

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program Patient Information Guide Page # Contents ..........................................................................................................................................1 Welcome! Welcome Letter ....................................................................................................................3 Important Things to Know Up Front ....................................................................................4 Meet Your Crohn’s & Colitis Team .....................................................................................6 How to Contact Us Crohn’s & Colitis Clinic Schedule .....................................................................................11 Physician and Nurse Contact Information..........................................................................12 Appointment Scheduling and Other Contact Information..................................................13 The Basics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Basic Information about Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) ...........................................14 Frequently Asked Questions about Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) ..........................18 Testing in IBD Colonoscopy and Flexible Sigmoidoscopy ........................................................................20 Upper Endoscopy ...............................................................................................................21 Capsule Endoscopy and Deep Enteroscopy .......................................................................22 -

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using Machine Learning

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy using Machine Learning Kate Wang et al. Supplemental Table S1. Drugs selected by Pharmacophore-based, ML-based and DL- based search in the FDA-approved drugs database Pharmacophore WEKA TF 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3- 5-O-phosphono-alpha-D- (phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)) ribofuranosyl diphosphate Acarbose Amikacin Acetylcarnitine Acetarsol Arbutamine Acetylcholine Adenosine Aldehydo-N-Acetyl-D- Benserazide Acyclovir Glucosamine Bisoprolol Adefovir dipivoxil Alendronic acid Brivudine Alfentanil Alginic acid Cefamandole Alitretinoin alpha-Arbutin Cefdinir Azithromycin Amikacin Cefixime Balsalazide Amiloride Cefonicid Bethanechol Arbutin Ceforanide Bicalutamide Ascorbic acid calcium salt Cefotetan Calcium glubionate Auranofin Ceftibuten Cangrelor Azacitidine Ceftolozane Capecitabine Benserazide Cerivastatin Carbamoylcholine Besifloxacin Chlortetracycline Carisoprodol beta-L-fructofuranose Cilastatin Chlorobutanol Bictegravir Citicoline Cidofovir Bismuth subgallate Cladribine Clodronic acid Bleomycin Clarithromycin Colistimethate Bortezomib Clindamycin Cyclandelate Bromotheophylline Clofarabine Dexpanthenol Calcium threonate Cromoglicic acid Edoxudine Capecitabine Demeclocycline Elbasvir Capreomycin Diaminopropanol tetraacetic acid Erdosteine Carbidopa Diazolidinylurea Ethchlorvynol Carbocisteine Dibekacin Ethinamate Carboplatin Dinoprostone Famotidine Cefotetan Dipyridamole Fidaxomicin Chlormerodrin Doripenem Flavin adenine dinucleotide -

The Efficacy of Probiotics, Prebiotic Inulin-Type Fructans, and Synbiotics in Human Ulcerative Colitis: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Supplementary Materials and Data of Review: The Efficacy of Probiotics, Prebiotic Inulin-Type Fructans, and Synbiotics in Human Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Supplementary Data S1 Search strategy Only clinical trial publications and human filters were used in the literature search performed in PUBMED. The studies were searched using the terms “ulcerative colitis” in combination with “probiotic”, “synbiotic”, and “inflammatory bowel disease” in combination with “prebiotic”, “inulin”, “FOS” and “fructo-oligosaccharides”. The search in SCOPUS was performed using combinations of the terms “ulcerative colitis” AND “inulin” limited to document types “Article”. Another search used “ulcerative colitis” AND “probiotic” AND “human” limited to document type “Article” and the subareas “Medicine”, “Immunology and Microbiology” and “Health Professions” and the exact key words “Controlled Study”, “Clinical Article”, “Clinical Trials”, “Controlled Clinical Trial” and “Double-Blind Method”. An additional search using the combinations “ulcerative colitis” AND “synbiotic” AND “human” limited to document type “Article” and excluding the exact key word “Crohn Disease”. In all cases, the search was limited to the languages “Spanish” and “English” Supplementary Table S1 Risk of bias of selected studies and and data data bias bias of generation generation assessment) reporting outcome concealment sources (participants personnel) personnel) Sequence (outcome Selective Other Allocation Incomplete Blinding Random Blinding Matsuoka et al. 2018 ? + + + + + + Tamaki et al. 2016 ? + + ? - ? + Yoshimatsu et al. 2015 ? ? + ? - + + Petersen et al. 2014 ? + + ? + + + Groeger et al. 2013 - - + ? - ? + Oliva et al. 2012 + + + ? - + + Wildt et al. 2011 ? + + ? + + + Tursi et al. 2010 ? + + ? + ? + Matthes et al. 2010 ? + + ? - + + Ng et al. 2010 ? - + ? + ? + Sood et al. 2009 + + + ? - ? + Miele et al. 2009 + + + ? - ? + Furrie et al. -

Stems for Nonproprietary Drug Names

USAN STEM LIST STEM DEFINITION EXAMPLES -abine (see -arabine, -citabine) -ac anti-inflammatory agents (acetic acid derivatives) bromfenac dexpemedolac -acetam (see -racetam) -adol or analgesics (mixed opiate receptor agonists/ tazadolene -adol- antagonists) spiradolene levonantradol -adox antibacterials (quinoline dioxide derivatives) carbadox -afenone antiarrhythmics (propafenone derivatives) alprafenone diprafenonex -afil PDE5 inhibitors tadalafil -aj- antiarrhythmics (ajmaline derivatives) lorajmine -aldrate antacid aluminum salts magaldrate -algron alpha1 - and alpha2 - adrenoreceptor agonists dabuzalgron -alol combined alpha and beta blockers labetalol medroxalol -amidis antimyloidotics tafamidis -amivir (see -vir) -ampa ionotropic non-NMDA glutamate receptors (AMPA and/or KA receptors) subgroup: -ampanel antagonists becampanel -ampator modulators forampator -anib angiogenesis inhibitors pegaptanib cediranib 1 subgroup: -siranib siRNA bevasiranib -andr- androgens nandrolone -anserin serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonists altanserin tropanserin adatanserin -antel anthelmintics (undefined group) carbantel subgroup: -quantel 2-deoxoparaherquamide A derivatives derquantel -antrone antineoplastics; anthraquinone derivatives pixantrone -apsel P-selectin antagonists torapsel -arabine antineoplastics (arabinofuranosyl derivatives) fazarabine fludarabine aril-, -aril, -aril- antiviral (arildone derivatives) pleconaril arildone fosarilate -arit antirheumatics (lobenzarit type) lobenzarit clobuzarit -arol anticoagulants (dicumarol type) dicumarol -

National Quality Forum

NQF #PSM-030-10 NATIONAL QUALITY FORUM Measure Evaluation 4.1 January 2010 This form contains the measure information submitted by stewards. Blank fields indicate no information was provided. Attachments also may have been submitted and are provided to reviewers. The sub-criteria and most of the footnotes from the evaluation criteria are provided in Word comments and will appear if your cursor is over the highlighted area (or in the margin if your Word program is set to show revisions in balloons). Hyperlinks to the evaluation criteria and ratings are provided in each section. TAP/Workgroup (if utilized): Complete all yellow highlighted areas of the form. Evaluate the extent to which each sub-criterion is met. Based on your evaluation, summarize the strengths and weaknesses in each section. Note: If there is no TAP or workgroup, the SC also evaluates the sub-criteria (yellow highlighted areas). Steering Committee: Complete all pink highlighted areas of the form. Review the workgroup/TAP assessment of the sub-criterion, noting any areas of disagreement; then evaluate the extent to which each major criterion is met; and finally, indicate your recommendation for the endorsement. Provide the rationale for your ratings. Evaluation ratings of the extent to which the criteria are met C = Completely (unquestionably demonstrated to meet the criterion) P = Partially (demonstrated to partially meet the criterion) M = Minimally (addressed BUT demonstrated to only minimally meet the criterion) N = Not at all (NOT addressed; OR incorrectly addressed; OR demonstrated to NOT meet the criterion) NA = Not applicable (only an option for a few sub-criteria as indicated) (for NQF staff use) NQF Review #: PSM-030-10 NQF Project: Patient Safety Measures MEASURE DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION De.1 Measure Title: Patient(s) with inflammatory bowel disease taking methotrexate, sulfasalazine, mercaptopurine, or azathioprine that had a CBC in last 3 reported months. -

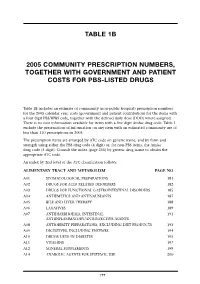

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03 -

2012 Harmonized Tariff Schedule Pharmaceuticals Appendix

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2014) (Rev. 1) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2014) (Rev. 1) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACEVALTRATE 25161-41-5 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACEXAMIC ACID 57-08-9 ABAGOVOMAB 792921-10-9 ACICLOVIR 59277-89-3 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABAPERIDONE 183849-43-6 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABATACEPT 332348-12-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABETIMUS 167362-48-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLIDINIUM BROMIDE 320345-99-1 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURIN 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENE 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDE 185106-16-5 -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 Bezwada (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US008O26285B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 BeZWada (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 27, 2011 (54) CONTROL RELEASE OF BIOLOGICALLY 6,955,827 B2 10/2005 Barabolak ACTIVE COMPOUNDS FROM 2002/0028229 A1 3/2002 Lezdey 2002fO169275 A1 11/2002 Matsuda MULT-ARMED OLGOMERS 2003/O158598 A1 8, 2003 Ashton et al. 2003/0216307 A1 11/2003 Kohn (75) Inventor: Rao S. Bezwada, Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2003/0232091 A1 12/2003 Shefer 2004/0096476 A1 5, 2004 Uhrich (73) Assignee: Bezwada Biomedical, LLC, 2004/01 17007 A1 6/2004 Whitbourne 2004/O185250 A1 9, 2004 John Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2005/0048121 A1 3, 2005 East 2005/OO74493 A1 4/2005 Mehta (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005/OO953OO A1 5/2005 Wynn patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2005, 0112171 A1 5/2005 Tang U.S.C. 154(b) by 423 days. 2005/O152958 A1 7/2005 Cordes 2005/0238689 A1 10/2005 Carpenter 2006, OO13851 A1 1/2006 Giroux (21) Appl. No.: 12/203,761 2006/0091034 A1 5, 2006 Scalzo 2006/0172983 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada (22) Filed: Sep. 3, 2008 2006,0188547 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada 2007,025 1831 A1 11/2007 Kaczur (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2009/0076174 A1 Mar. 19, 2009 EP OO99.177 1, 1984 EP 146.0089 9, 2004 Related U.S. Application Data WO WO9638528 12/1996 WO WO 2004/008101 1, 2004 (60) Provisional application No. 60/969,787, filed on Sep. WO WO 2006/052790 5, 2006 4, 2007. -

List of 219 Inns, Including E75 and T50 Marking

List of 219 INNs, including E75 and T50 marking ACARBOSE * ADALIMUMAB # ADRAFINIL ALENDRONIC ACID # * ALFUZOSIN * AMISULPRIDE * AMITRIPTYLINE AMLODIPINE # * AMOROLFINE * AMOXICILLIN + CLAVULANIC AMOXICILLIN + LANSOPRAZOLE ANASTROZOLE # ACID # * + CLARITHROMYCIN * ATENOLOL # ATORVASTATIN # AZITHROMYCIN * BALSALAZIDE * BECLOMETASONE # BENAZEPRIL * BISOPROLOL * BRIMONIDINE * BRIVUDINE * BUDESONIDE # * BUDESONIDE + FORMOTEROL # BUFLOMEDIL BUPRENORPHINE BUSERELIN * CABERGOLINE * CALCIPOTRIOL * CALCIPOTRIOL + CANDESARTAN CILEXETIL # BETAMETHASONE * CANDESARTAN CILEXETIL + CAPSAICIN CAPTOPRIL + HYDROCHLOROTHIAZIDE HYDROCHLOROTHIAZIDE * CARTEOLOL * CARVEDILOL * CEFATRIZINE * CEFIXIME * CEFPODOXIME PROXETIL # * CEFTIBUTEN * CEFTRIAXONE * CEFUROXIME AXETIL * CELECOXIB # CELIPROLOL * CETIRIZINE * CICLETANINE * CICLOSPORIN * CIPROFIBRATE * CIPROFLOXACIN * CISAPRIDE * CITALOPRAM # * CLARITHROMYCIN * CLODRONIC ACID CLOPIDOGREL # CROMOGLICIC ACID + REPROTEROL * CYPROTERONE + DALTEPARIN SODIUM * DARBEPOETIN ALFA # ETHINYLESTRADIOL DESOGESTREL + DIACEREIN * DICLOFENAC # ETHINYLESTRADIOL * DIENOGEST + DOMPERIDONE * DONEPEZIL # ETHINYLESTRADIOL * DOXAZOSIN # * EBASTINE * ENALAPRIL # * ENOXAPARIN SODIUM # EPOETIN ALFA # * EPOETIN BETA # ESOMEPRAZOLE # ESTRADIOL * ESTRADIOL + NORETHISTERONE * ETANERCEPT # ETHINYLESTRADIOL + ETIDRONIC ACID * GESTODENE * ETODOLAC EZETIMIBE # FELODIPINE * FENOFIBRATE # FENTANYL # * FEXOFENADINE * FINASTERIDE * FLECAINIDE FLUCONAZOLE * FLUOXETINE # * FLUPIRTINE * FLUTICASONE # * FORMOTEROL FOSFOMYCIN TROMETAMOL * FOSINOPRIL * -

IG Living August-September 2010

IMMUNE GLOBULIN COMMUNITY www.IGLiving.com August-September 20010 1 0 for Exercise Options for CIDP Patients A Review of Medicare and Disability Programs How Patients Can Connect With a Community WHAT DOES YOUR GUT SAY? TREATING IBS AND IBD — PAGE 42 HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION CONTRAINDICATIONS ADVERSE REACTIONS These highlights do not include all the information • Anaphylactic or severe systemic reactions to Most common adverse reactions with an incidence needed to use octagam®, Immune Globulin human immunoglobulin of > 5% during a clinical trial were headache and Intravenous (Human), safely and effectively. • IgA deficient patients with antibodies against nausea. To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, IgA and a history of hypersensitivity contact Octapharma at 1-866-766-4860 or ® • Patients with acute hypersensitivity reaction FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch OCTAGAM to corn Immune Globulin Intravenous DRUG INTERACTIONS WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS • The passive transfer of antibodies may confound (Human) 5% Liquid Preparation • IgA deficient patients with antibodies against the results of serological testing. IgA are at greater risk of developing severe • The passive transfer of antibodies may interfere Initial U.S. Approval: 2004 hypersensitivity and anaphylactic reactions. with the response to live viral vaccines. RECENT MAJOR CHANGES Epinephrine should be available immediately to Warnings and Precautions - Hyperproteinemia 8/2008 treat any acute severe hypersensitivity reactions. USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS • Monitor renal function, including blood urea • Pregnancy: no human or animal data. WARNING: ACUTE RENAL DYSFUNCTION nitrogen and serum creatinine, and urine Use only if clearly needed. and RENAL FAILURE output in patients at risk of developing acute • In patients over age 65 or in any person at risk See full prescribing information for renal failure. -

Low Dose Balsalazide (1.5 G Twice Daily) and Mesalazine

Gut 2001;49:783–789 783 Evangelisches Low dose balsalazide (1.5 g twice daily) and Krankenhaus Kalk, Teaching Hospital of the University of mesalazine (0.5 g three times daily) maintained Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.49.6.783 on 1 December 2001. Downloaded from Cologne, Germany W Kruis remission of ulcerative colitis but high dose I Medizinische Klinik, balsalazide (3.0 g twice daily) was superior in Christian-Albrechts- University Kiel, preventing relapses Germany S Schreiber Gastroenterologische W Kruis, S Schreiber, D Theuer, J-W Brandes, E Schütz, S Howaldt, B Krakamp, Praxis, Heilbronn, J Hämling, H Mönnikes, I Koop, M Stolte, D Pallant, U Ewald Germany D Theuer Medizinische Klinik I, Abstract remission in patients with ulcerative coli- Städtisches Klinikum, Background—Balsalazide is a new tis compared with a low dose (1.5 g twice Braunschweig, Germany 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) containing daily) or a standard dose of mesalazine J-W Brandes prodrug. Its eYcacy in comparison with (0.5 g three times daily). All three treat- standard mesalazine therapy and the ments were safe and well tolerated. Castra Regina Centre, optimum dose for maintaining remission (Gut 2001;49:783–789) Regensburg, Germany of ulcerative colitis are still unclear. E Schütz Aims—To compare the relapse preventing Keywords: balsalazide; mesalazine; aminosalicylic acid; ulcerative colitis Medizinische eVect and safety profile of two doses of Kernklinik und balsalazide and a standard dose of Poliklinik, University Eudragit coated mesalazine. Hamburg, Germany Methods—A total of 133 patients with Treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) S Howaldt ulcerative colitis in remission were re- containing drugs is the gold standard for main- cruited to participate in a double blind, taining remission in patients with ulcerative Medizinische Klinik I, colitis (UC).