A RODENT and a PECCARY from the CENOZOIC of COLOMBIA By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Dakota to Nebraska

Geological Society of America Special Paper 325 1998 Lithostratigraphic revision and correlation of the lower part of the White River Group: South Dakota to Nebraska Dennis O. Terry, Jr. Department of Geology, University of Nebraska—Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588-0340 ABSTRACT Lithologic correlations between type areas of the White River Group in Nebraska and South Dakota have resulted in a revised lithostratigraphy for the lower part of the White River Group. The following pedostratigraphic and lithostratigraphic units, from oldest to youngest, are newly recognized in northwestern Nebraska and can be correlated with units in the Big Badlands of South Dakota: the Yellow Mounds Pale- osol Equivalent, Interior and Weta Paleosol Equivalents, Chamberlain Pass Forma- tion, and Peanut Peak Member of the Chadron Formation. The term “Interior Paleosol Complex,” used for the brightly colored zone at the base of the White River Group in northwestern Nebraska, is abandoned in favor of a two-part division. The lower part is related to the Yellow Mounds Paleosol Series of South Dakota and rep- resents the pedogenically modified Cretaceous Pierre Shale. The upper part is com- posed of the unconformably overlying, pedogenically modified overbank mudstone facies of the Chamberlain Pass Formation (which contains the Interior and Weta Paleosol Series in South Dakota). Greenish-white channel sandstones at the base of the Chadron Formation in Nebraska (previously correlated to the Ahearn Member of the Chadron Formation in South Dakota) herein are correlated to the channel sand- stone facies of the Chamberlain Pass Formation in South Dakota. The Chamberlain Pass Formation is unconformably overlain by the Chadron Formation in South Dakota and Nebraska. -

Hoganson, J.W., 2009. Corridor of Time Prehistoric Life of North

Corridor of Time Prehistoric Life of North Dakota Exhibit at the North Dakota Heritage Center Completed by John W. Hoganson Introduction In 1989, legislation was passed that directed the North Dakota and a laboratory specialist, a laboratory for preparation of Geological Survey to establish a public repository for North fossils, and a fossil storage area. The NDGS paleontology staff, Dakota fossils. Shortly thereafter, the Geological Survey signed now housed at the Heritage Center, consists of John Hoganson, a Memorandum of Agreement with the State Historical Society State Paleontologist, and paleontologists Jeff Person and Becky of North Dakota which provided space in the North Dakota Gould. This arrangement has allowed the Geological Survey, in Heritage Center for development of this North Dakota State collaboration with the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Fossil Collection, including offices for the curator of the collection to create prehistoric life of North Dakota exhibits at the Heritage Center and displays of North Dakota fossils at over 20 other museums and interpretive centers around the state. The first of the Heritage Center prehistoric life exhibits was the restoration of the Highgate Mastodon skeleton in the First People exhibit area (fig. 1). Mastodons were huge, elephant- like mammals that roamed North America at the end of the last Ice Age about 11,000 years ago. This exhibit was completed in 1992 and was the first restored skeleton of a prehistoric animal ever displayed in North Dakota. The mastodon exhibit was, and still is, a major attraction in the Heritage Center. Because of its popularity, it was decided that additional prehistoric life displays should be included in the Heritage Center exhibit plans. -

Illustratedencycloped Iadinosaursandprehist

I L L U S T R A T E D E N C Y C L Baryonyx THEROPODS F A C T F I L E O # Tyrannosaurus Rex’s head was about 1.5 m long. Its lower jaw was hinged in such heropods were a group of mostly a way as to maximize its gape. An eight-year- P meat-eating saurischian ( 13) or old child could have squatted in its jaws. “lizard hipped” dinosaurs. They all T # Compsognathus, discovered in Germany had three toes and their name means in the 1850s, was the first ever dinosaur to E “beast-footed”. Theropods were the first be found as a complete skeleton. kind of dinosaur to evolve. They had large # Most experts agree that birds evolved eyes and long tails.They ran on their two Baryonyx A meat-eating dinosaur from the Compsognathus A tiny meat-eating from small dinosaurs. Archaeopteryx, the D strong back legs, leaving their arms free to Cretaceous period. It had the body of a dinosaur from the Late Jurassic. It was first known bird, is closely related to the raptors and may have evolved directly from grasp or pin down their prey. They ranged large carnivore, about eight metres long, about the size of a chicken and preyed on them. The presence of small bumps or quill in size from tiny Compsognathus, the size but its skull was long and narrow, with insects and lizards. It was probably the bones on a Velociraptor fossil I of a chicken, to 18 m long Spinosaurus. -

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abalosia U.Pliocene S America Abelmoschomys U.Miocene E USA A

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abalosia U.Pliocene S America Abelmoschomys U.Miocene E USA A. simpsoni U.Miocene Florida(US) Abra see Ochotona Abrana see Ochotona Abrocoma U.Miocene-Recent Peru A. oblativa 60 cm? U.Holocene Peru Abromys see Perognathus Abrosomys L.Eocene Asia Abrothrix U.Pleistocene-Recent Argentina A. illuteus living Mouse Lujanian-Recent Tucuman(ARG) Abudhabia U.Miocene Asia Acanthion see Hystrix A. brachyura see Hystrix brachyura Acanthomys see Acomys or Tokudaia or Rattus Acarechimys L-M.Miocene Argentina A. minutissimus Miocene Argentina Acaremys U.Oligocene-L.Miocene Argentina A. cf. Murinus Colhuehuapian Chubut(ARG) A. karaikensis Miocene? Argentina A. messor Miocene? Argentina A. minutissimus see Acarechimys minutissimus Argentina A. minutus Miocene? Argentina A. murinus Miocene? Argentina A. sp. L.Miocene Argentina A. tricarinatus Miocene? Argentina Acodon see Akodon A. angustidens see Akodon angustidens Pleistocene Brazil A. clivigenis see Akodon clivigenis Pleistocene Brazil A. internus see Akodon internus Pleistocene Argentina Acomys L.Pliocene-Recent Africa,Europe,W Asia,Crete A. cahirinus living Spiny Mouse U.Pleistocene-Recent Israel A. gaudryi U.Miocene? Greece Aconaemys see Pithanotomys A. fuscus Pliocene-Recent Argentina A. f. fossilis see Aconaemys fuscus Pliocene Argentina Acondemys see Pithanotomys Acritoparamys U.Paleocene-M.Eocene W USA,Asia A. atavus see Paramys atavus A. atwateri Wasatchian W USA A. cf. Francesi Clarkforkian Wyoming(US) A. francesi(francesci) Wasatchian-Bridgerian Wyoming(US) A. wyomingensis Bridgerian Wyoming(US) Acrorhizomys see Clethrionomys Actenomys L.Pliocene-L.Pleistocene Argentina A. maximus Pliocene Argentina Adelomyarion U.Oligocene France A. vireti U.Oligocene France Adelomys U.Eocene France A. -

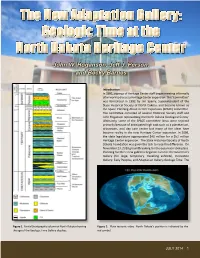

The New Adaption Gallery

Introduction In 1991, a group of Heritage Center staff began meeting informally after work to discuss a Heritage Center expansion. This “committee” was formalized in 1992 by Jim Sperry, Superintendent of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, and became known as the Space Planning About Center Expansion (SPACE) committee. The committee consisted of several Historical Society staff and John Hoganson representing the North Dakota Geological Survey. Ultimately, some of the SPACE committee ideas were rejected primarily because of anticipated high cost such as a planetarium, arboretum, and day care center but many of the ideas have become reality in the new Heritage Center expansion. In 2009, the state legislature appropriated $40 million for a $52 million Heritage Center expansion. The State Historical Society of North Dakota Foundation was given the task to raise the difference. On November 23, 2010 groundbreaking for the expansion took place. Planning for three new galleries began in earnest: the Governor’s Gallery (for large, temporary, travelling exhibits), Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples, and Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time. The Figure 1. Partial Stratigraphic column of North Dakota showing Figure 2. Plate tectonic video. North Dakota's position is indicated by the the age of the Geologic Time Gallery displays. red symbol. JULY 2014 1 Orientation Featured in the Orientation area is an interactive touch table that provides a timeline of geological and evolutionary events in North Dakota from 600 million years ago to the present. Visitors activate the timeline by scrolling to learn how the geology, environment, climate, and life have changed in North Dakota through time. -

Miocene Development of Life

Miocene Development of Life Jarðsaga 2 - Saga Lífs og Lands - Ólafur Ingólfsson Thehigh-pointof theage of mammals The Miocene or "less recent" is so called because it contains fewer modern animals than the following Pliocene. The Miocene lasted for 18 MY, ~23-5 MY ago. This was a huge time of transition, the end of the old prehistoric world and the birth of the more recent sort of world. It was also the high point of the age of mammals Open vegetation systems expand • The overall pattern of biological change for the Miocene is one of expanding open vegetation systems (such as deserts, tundra, and grasslands) at the expense of diminishing closed vegetation (such as forests). • This led to a rediversification of temperate ecosystems and many morphological changes in animals. Mammals and birds in particular developed new forms, whether as fast-running herbivores, large predatory mammals and birds, or small quick birds and rodents. Two major ecosystems evolve Two major ecosystems first appeared during the Miocene: kelp forests and grasslands. The expansion of grasslands is correlated to a drying of continental interiors and a global cooling. Later in the Miocene a distinct cooling of the climate resulted in the further reduction of both tropical and conifer forests, and the flourishing of grasslands and savanna in their stead. Modern Grasslands Over one quarter of the Earth's surface is covered by grasslands. Grasslands are found on every continent except Antarctica, and they make up most of Africa and Asia. There are several types of grassland and each one has its own name. -

The Largest Fossil Rodent Andre´S Rinderknecht1 and R

Proc. R. Soc. B doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1645 Published online The largest fossil rodent Andre´s Rinderknecht1 and R. Ernesto Blanco2,* 1Museo Nacional de Historia Natural y Antropologı´a, Montevideo 11300, Uruguay 2Facultad de Ingenierı´a, Instituto de Fı´sica, Julio Herrera y Reissig 565, Montevideo 11300, Uruguay The discovery of an exceptionally well-preserved skull permits the description of the new South American fossil species of the rodent, Josephoartigasia monesi sp. nov. (family: Dinomyidae; Rodentia: Hystricognathi: Caviomorpha). This species with estimated body mass of nearly 1000 kg is the largest yet recorded. The skull sheds new light on the anatomy of the extinct giant rodents of the Dinomyidae, which are known mostly from isolated teeth and incomplete mandible remains. The fossil derives from San Jose´ Formation, Uruguay, usually assigned to the Pliocene–Pleistocene (4–2 Myr ago), and the proposed palaeoenviron- ment where this rodent lived was characterized as an estuarine or deltaic system with forest communities. Keywords: giant rodents; Dinomyidae; megamammals 1. INTRODUCTION 3. HOLOTYPE The order Rodentia is the most abundant group of living MNHN 921 (figures 1 and 2; Museo Nacional de Historia mammals with nearly 40% of the total number of Natural y Antropologı´a, Montevideo, Uruguay): almost mammalian species recorded (McKenna & Bell 1997; complete skull without left zygomatic arch, right incisor, Wilson & Reeder 2005). In general, rodents have left M2 and right P4-M1. body masses smaller than 1 kg with few exceptions. The largest living rodent, the carpincho or capybara 4. AGE AND LOCALITY (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), which lives in the Neotro- Uruguay, Departament of San Jose´, coast of Rı´odeLa pical region of South America, has a body mass of Plata, ‘Kiyu´’ beach (348440 S–568500 W). -

4. Palaeontology

118 4. Palaeontology Lionel Cavin, Damien Becker, Christian Klug Swiss Geological Survey – swisstopo, Schweizerisches Komitee für Stratigraphie, Naturhistorisches Museum Bern, Symposium 4: Palaeontology Schweizerische Paläontologische Gesellschaft, Kommission des Schweizerischen Paläontologischen Abhandlungen (KSPA) TALKS: 4.1 Aguirre-Fernández, G., Carrillo-Briceño, J. D., Sánchez, R., Jaramillo, C., Sánchez-Villagra, M. R.: Fossil whales and dolphins (Cetacea) from the Miocene of Venezuela and Colombia 4.2 Anquetin J.: A new diverse turtle fauna in the late Kimmeridgian of Switzerland 4.3 Bagherpour B., Bucher H., Brosse M., Baud A., Frisk Å., Guodun K.: Tectonic control on the deposition of Permian-Triassic boundary microbialites in the Nanpanjiang Basin (South China) 4.4 Carrillo J. D., Carlini A. A., Jaramillo C., Sánchez-Villagra M. R.: New fossil mammals from the northern neotropics (Urumaco, Venezuela, Castilletes, Colombia) and their significance for the new world diversity patterns and the Great American Biotic Interchange 4.5 Costeur L., Mennecart B., Rössner G.E., Azanza B.,: Inner ear in earyl deer 4.6 Hiard F., Métais G., Goussard F.: On the “thumb” of anoplotheriins: a 3D comparative study of the hand of Anoplotherium and Diplobune. 4.7 Klug C., Hoffmann R.: The origin of the complexity of ammonoid sutures 4.8 Koppka, J.: The oysters (Ostreoidea, Bivalvia) of the Reuchenette Formation (Kimmeridgian, Upper Jurassic) in Northwestern Switzerland 4.9 Leuzinger L., Kocsis L., Billon-Bruyat J.-P., Spezzaferri S.: Taxonomy and biogeochemistry of a new chondrichthyan fauna from the Swiss Jura (Kimmeridgian): an unusual isotopic signature for the hybodont shark Asteracanthus 4.10 Maridet O., Costeur L., Schwarz C., Furió M., van Glabbeek F. -

Fundamentals of Biogeography

FUNDAMENTALS OF BIOGEOGRAPHY Fundamentals of Biogeography presents an engaging and comprehensive introduction to biogeography, explaining the ecology, geography, and history of animals and plants. Defining and explaining the nature of populations, communities and ecosystems, the book examines where different animals and plants live and how they came to be living there; investigates how populations grow, interact, and survive, and how communities are formed and change; and predicts the shape of communities in the twenty-first century. Illustrated throughout with informative diagrams and attractive photos (many in colour), and including guides to further reading, chapter summaries, and an extensive glossary of key terms, Fundamentals of Biogeography clearly explains key concepts, life systems, and interactions. The book also tackles the most topical and controversial environmental and ethical concerns including: animal rights, species exploitation, habitat fragmentation, biodiversity, metapopulations, patchy landscapes, and chaos. Fundamentals of Biogeography presents an appealing introduction for students and all those interested in gaining a deeper understanding of the key topics and debates within the fields of biogeography, ecology and the environment. Revealing how life has and is adapting to its biological and physical surroundings, Huggett stresses the role of ecological, geographical, historical and human factors in fashioning animal and plant distributions and raises important questions concerning how humans have altered Nature, and how biogeography can affect conservation practice. Richard John Huggett is a Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Manchester ROUTLEDGE FUNDAMENTALS OF PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY SERIES Series Editor: John Gerrard This new series of focused, introductory textbooks presents comprehensive, up-to-date introductions to the fundamental concepts, natural processes and human/environmental impacts within each of the core physical geography sub-disciplines: Biogeography, Climatology, Hydrology, Geomorphology and Soils. -

Actualización Del Conocimiento De Los Roedores Del Mioceno Tardío De La Mesopotamia Argentina: Aspectos Sistemáticos, Evolutivos Y Paleobiogeográficos

El Neógeno de la Mesopotamia argentina. D. Brandoni y J.I. Noriega, Editores (2013) Asociación Paleontológica Argentina, Publicación Especial 14: 147–163 ACTUALIZACIÓN DEL CONOCIMIENTO DE LOS ROEDORES DEL MIOCENO TARDÍO DE LA MESOPOTAMIA ARGENTINA: ASPECTOS SISTEMÁTICOS, EVOLUTIVOS Y PALEOBIOGEOGRÁFICOS NORMA L. NASIF1, ADRIANA M. CANDELA2, LUCIANO RASIA2, M. CAROLINA MADOZZO JAÉN1 y RICARDO BONINI2 1Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Miguel Lillo 205, 4000, San Miguel de Tucumán,Tucumán. [email protected], [email protected] 2Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Paseo del Bosque S/N, 1900, La Plata, Buenos Aires. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Resumen. Los roedores registrados en el “Conglomerado osífero”, aflorante en la base de la Formación Ituzaingó (=“Mesopotamiense”, Mioceno Tardío, Edad Mamífero Huayqueriense), pertenecen al grupo de los caviomorfos. En esta unidad, éstos muestran una importante diversidad de especies, representantes de todas las superfamilias y casi todas las familias reconocidas en este infraorden. Presentan una notable variedad de patrones morfológicos, tales como rangos amplios de tamaño corporal y diferentes grados de complejidad dentaria e hipsodoncia. Ambos atributos, diversidad taxonómica y disparidad morfológica, le otorgan a las especies del “Mesopotamiense” una particular importancia para el entendimiento de aspectos evolutivos y biogeográficos en el contexto de la historia de los caviomorfos -

2014BOYDANDWELSH.Pdf

Proceedings of the 10th Conference on Fossil Resources Rapid City, SD May 2014 Dakoterra Vol. 6:124–147 ARTICLE DESCRIPTION OF AN EARLIEST ORELLAN FAUNA FROM BADLANDS NATIONAL PARK, INTERIOR, SOUTH DAKOTA AND IMPLICATIONS FOR THE STRATIGRAPHIC POSITION OF THE BLOOM BASIN LIMESTONE BED CLINT A. BOYD1 AND ED WELSH2 1Department of Geology and Geologic Engineering, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City, South Dakota 57701 U.S.A., [email protected]; 2Division of Resource Management, Badlands National Park, Interior, South Dakota 57750 U.S.A., [email protected] ABSTRACT—Three new vertebrate localities are reported from within the Bloom Basin of the North Unit of Badlands National Park, Interior, South Dakota. These sites were discovered during paleontological surveys and monitoring of the park’s boundary fence construction activities. This report focuses on a new fauna recovered from one of these localities (BADL-LOC-0293) that is designated the Bloom Basin local fauna. This locality is situated approximately three meters below the Bloom Basin limestone bed, a geographically restricted strati- graphic unit only present within the Bloom Basin. Previous researchers have placed the Bloom Basin limestone bed at the contact between the Chadron and Brule formations. Given the unconformity known to occur between these formations in South Dakota, the recovery of a Chadronian (Late Eocene) fauna was expected from this locality. However, detailed collection and examination of fossils from BADL-LOC-0293 reveals an abundance of specimens referable to the characteristic Orellan taxa Hypertragulus calcaratus and Leptomeryx evansi. This fauna also includes new records for the taxa Adjidaumo lophatus and Brachygaulus, a biostratigraphic verifica- tion for the biochronologically ambiguous taxon Megaleptictis, and the possible presence of new leporid and hypertragulid taxa. -

Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest Or Cultural Parkland?

R E P O R T S tant role in locomotor propulsion than the fore- Ϫ1.678 ϩ 2.518 (1.80618), W ϭ 741.1; anteropos- phylogeny place Lagostomus together with Chin- limbs, which were probably important in food terior distal humerus diameter (APH): log W ϭ chilla (22). Ϫ1.467 ϩ 2.484 (1.6532), W ϭ 436.1 kg. 25. M. S. Springer et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, manipulation. Because of this, the body mass 17. A. R. Biknevicius, J. Mammal. 74, 95 (1993). 6241 (2001). estimation based on the femur is more reliable: 18. The humerus/femur length ratio (H/F) and the (humer- 26. We thank J. Bocquentin, A. Ranci, A. Rinco´n, J. Reyes, P. pattersoni probably weighed ϳ700 kg. With us ϩ radius)/(femur ϩ tibia) length ratio [(H ϩ R)/(F ϩ D. Rodrigues de Aguilera, and R. S´anchez for help with Phoberomys, the size range of the order is in- T )] in P. pattersoni (0.76 and 0.78, respectively) are fieldwork; J. Reyes and E. Weston for laboratory work; average compared with those of other caviomorphs. For E. Weston and three anonymous reviewers for com- creased and Rodentia becomes one of the mam- a sample of 17 extant caviomorphs, the mean values Ϯ ments on the manuscript; O. Aguilera Jr. for assist- malian orders with the widest size variation, SD were H/F ϭ 0.80 Ϯ 0.08 and (H ϩ R)/(F ϩ T ) ϭ ance with digital imaging; S. Melendrez for recon- second only to the Diprotodontia (kangaroos, 0.74 Ϯ 0.09.