Human Rights Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Free QR Code Reader App

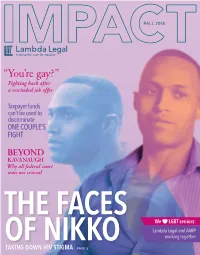

FALL 2018 “You’re gay? ” Fighting back after a rescinded job offer Taxpayer funds can’t be used to discriminate ONE COUPLE’S FIGHT BEYOND K AVANAUGH Why all federal court seats are crucial THE FACES We N LGBT seniors: Lambda Legal and AARP OF NIKKO working together TAKING DOWN HIV STIGMA PAGE 8 One Nation. One Set of Laws for All. Sheppard Mullin is proud to support its LGBTQ professionals and salutes Lambda Legal’s efforts to secure equality for all. Beijing | Brussels | Century City | Chicago | Dallas | London | Los Angeles | New York | Orange County Palo Alto | San Diego (Downtown) | San Diego (Del Mar) | San Francisco | Seoul | Shanghai | Washington, D.C. www.sheppardmullin.com Stand Out. Be Proud. Sidley is honored to continue our support of Lambda Legal and applauds its tireless dedication to achieving equality for the LGBTQ community. Find out how we are standing up for equality at sidley.com/diversity Sally Olson Chief Diversity Officer One South Dearborn Chicago, IL 60603 Attorney Advertising - Sidley Austin LLP, One South Dearborn, Chicago, IL 60603. AMERICA • ASIA PACIFIC • EUROPE | +1 3122 853 7000.LAMBDA Prior results LEGAL do IMPACT not guarantee Summer a similar 2018 outcome. MN-8919 sidley.com THANK YOU FOR BELIEVING Dear Lambda Legal family, As we wish our outgoing CEO Rachel B. Tiven well on community to fight for the kind of country that we want her new endeavors, our eyes are focused on the future. The ours to be. threats we currently face are meant to strike fear in the hearts We approach this task with resolve but also with humil- of the LGBTQ community and everyone living with HIV. -

Aclu Ar Covers R.Qxd

The Annual Update of the ACLU’s Nationwide Work on LGBT Rights and HIV/AIDS WhoWho We We Are Are 2005 2005 The Annual Update of the ACLU’s Nationwide Work on LGBT Rights and HIV/AIDS WHO WE ARE 2005 PARADOX, PROGRESS & SO ON . .1 FREEDOM RIDE: THE STORY OF TAKIA AND JO . .5 RELATIONSHIPS DOCKET . .7 WHAT MAKES A PARENT . .19 PARENTING DOCKET . .21 THE QUEER GUY AT HUNT HIGH . .25 YOUTH & SCHOOLS DOCKET . .27 LIFE’S CRUEL CHALLENGES . .31 DISCRIMINATION DOCKET . .33 TRANSLATINAS AND THE FIGHT FOR DERECHOS CIVILES . .37 TRANSGENDER DOCKET . .41 THE HARD TRUTH ABOUT SMALL TOWN PREJUDICE . .43 HIV/AIDS DOCKET . .45 HOW THE ACLU WORKS . .47 PROJECT STAFF . .49 COOPERATING ATTORNEYS . .51 CONTRIBUTORS . .53 Design: Carol Grobe Design 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004-2400 212.549.2627 [email protected] www.aclu.org Paradox, Progress & So On BY MATT COLES, PROJECT DIRECTOR The LGBT movement is at a pivotal moment in its sexual orientation. But just after the year ended, the a remarkable pace, none history. 2004 was a year of both remarkable progress U.S. Supreme Court let stand a lower court ruling of our recent gains is and stunning setbacks. For the first time, same-sex upholding Florida’s ban on adoption. And legislators in secure and continued couples were married in the United States – in Arkansas are already trying to undo the Little Rock progress is not assured. Massachusetts, San Francisco, Portland, Oregon, and judge’s decision. There are two forces at New Paltz, New York. -

Transgender Movement

New Trump Administration Memo on Obama Order Alarms LGBT Advocates Community Bonds Over Scoring Goals in the Detroit Drive Soccer League TRANS SINGER MOVED FELLOW MICHIGAN INMATES. NOW? AN ALBUM. WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM AUGUST 23, 2018 | VOL. 2634 | FREE Join The Conversation @ Pridesource.com SAVE THE DATE PROFILE WAYNE’S WORLD A Local Designer’s Breathable, Butt- Hugging Underwear Line for Men Who Want to Feel COVER Comfortable While 16 Trans Singer Moved Fellow Michigan Inmates. Feeling Sexy Now? An Album. CONFERENCE NEWS Queering Racial Justice Heads to Detroit 6 Sue Carter Runs for WSU Board of Governors 6 Wade Rakes Runs for U of M Board of Regents See Page 22 See Page 14 7 Trump Administration Memo on Obama Order Alarms LGBT Advocates 12 Promoting Pride 12 Team-WERK HAPPENINGS NATIONAL NEWS ELECTION 2018 OPINION 8 Parting Glances 8 Viewpoint 9 Creep of the Week LIFE 14 Wayne’s World 18 Happenings 21 Puzzle and Crossword 20 The Frivolist: 7 Gay Tips for Throwing the Perfect Labor Day Party 26 Deep Inside Hollywood COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS 22 Detroit Repertory Theatre Hosts Second Arts & IN CONCERT JOE BIDEN VERMONT Culture Festival Sarah Shook & the Disarmers at OTUS Foundation Launches Campaign In First, Trans Candidate Wins Major Party 22 Affirmations Hosts Golden Girls Trivia Party Supply in Ferndale Promoting LGBTQ Acceptance Nomination for Governor’s Race 22 Queering Racial Justice Heads to Detroit See Page 18 24 Third Annual Strand with Trans Family Picnic See Page 11 See Page 10 Draws Record Crowd 22 Mom to Mom Sale in Ferndale on Aug. -

Top DOJ Lawyer Joins Lambda Legal Staffing up to Fight the Trump Administration, Lambda Legal Brings on Sharon Mcgowan As Director of Strategy

Top DOJ Lawyer Joins Lambda Legal Staffing up to fight the Trump Administration, Lambda Legal brings on Sharon McGowan as Director of Strategy (New York, February 1, 2017) — Today, Lambda Legal announced the hiring of Sharon McGowan, a top attorney in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, as the organization’s new Director of Strategy. “Sharon McGowan is one of the most influential and effective LGBT rights lawyers in the country,” said Rachel B. Tiven, CEO of Lambda Legal. “At the Department of Justice, Sharon has been a forceful voice for our community, helping usher in an unprecedented era of progress for LGBT rights. She has had a hand in virtually every major achievement on LGBT rights to come out of President Obama’s administration, from the department’s decision to stop defending DOMA to its position that discrimination on the basis of sex encompasses discrimination on the basis of gender identity. She is a brilliant legal thinker and formidable advocate. As Lambda Legal prepares to vigorously defend LGBT rights during the Trump presidency, Sharon will be an indispensable part of our team.” “Our community has made tremendous strides since I first worked with Lambda Legal almost fifteen years ago as part of the litigation team on Lawrence v. Texas,” said Sharon McGowan, Lambda Legal’s new Director of Strategy. “From that landmark decision to securing nationwide marriage equality in Obergefell v. Hodges, Lambda Legal has played an unparalleled role in extending our country’s promise of equality to the LGBT community. I’m honored to join this historic organization and to continue fighting for our community in this new role.” More on Lambda Legal and the organization’s fight back against discrimination at www.lambdalegal.org. -

1 Testimony of Sharon M. Mcgowan Chief Strategy Officer and Legal

Testimony of Sharon M. McGowan Chief Strategy Officer and Legal Director, Lambda Legal Defense & Education Fund, Inc. Former Principal Deputy Chief, Appellate Section, U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division Testimony before the United States House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Hearing on “Oversight of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice” September 24, 2020 Good morning, and let me begin by thanking Chairman Cohen, Ranking Member Johnson, Chairman Nadler, and the other distinguished members of the Committee for the invitation to testify today as part of this incredibly important oversight hearing regarding the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice. My name is Sharon McGowan, and I currently serve as the Chief Strategy Officer and Legal Director of Lambda Legal Defense & Education Fund, Inc. (“Lambda Legal”), the oldest and largest national legal organization dedicated to achieving full recognition of the civil rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (“LGBTQ”) people and everyone living with HIV through impact litigation, education and public policy work. Immediately prior to joining Lambda Legal, I was proud to serve as the Principal Deputy Chief of the Appellate Section of the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice. I first joined the Civil Rights Division as a line lawyer in the Appellate Section in February 2010. I served in that role for approximately three years. After a stint at the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, I returned to the Justice Department in September 2014, when I was selected for an open Deputy Chief position in the Appellate Section. -

Cause Lawyers Inside the State

CAUSE LAWYERS INSIDE THE STATE Douglas NeJaime* Scholarship on the legal profession tends to situate cause lawyers in a state of adversarial tension with government lawyers. In this traditional paradigm, cause lawyers challenge the agenda of government attorneys, who represent institutional interests and the status quo. From this oppositional perspective, socio-legal scholars explore the activity of lawyers working at public interest law firms, for general social movement organizations, and in private practice. For some time, however, cause lawyers have moved in and out of government, thus complicating the conventional picture of lawyer-state opposition. This Article aims to identify and understand the significant role that cause lawyers play inside the state. It does so by drawing on recent social movement scholarship exploring the overlapping and interdependent relationship between movements and the state. Ultimately, this Article identifies four key impacts that cause lawyers within the state may produce: (1) reforming the state itself; (2) shaping state personnel and priorities; (3) harnessing state power to advance shared movement-state goals; and (4) facilitating and mediating relationships between the movement and the state. These productive functions, however, also come with significant limitations. By appealing to governmental authority and involving the state as a pro-movement force, cause lawyers in government positions may channel movement activity toward moderate goals and into institutional, state-centered tactics. Accordingly, this Article explores not only the benefits but also the costs of cause lawyer movement in and out of the state. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 650 I. LAWYER-STATE RELATIONSHIPS IN CAUSE LAWYERING SCHOLARSHIP ................................................................................. 656 * Associate Professor of Law, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles (Loyola Marymount University). -

In a Letter Delivered to the Senate Judiciary Committee's Chairman Chuck Grassley and Ranking Member Dianne

October 9, 2018 The Honorable Charles Grassley Chairman Senate Committee on the Judiciary 224 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Dianne Feinstein Ranking Member Senate Committee on the Judiciary 152 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 RE: 27 LGBT Groups Oppose Confirmation of Eric Murphy and Chad Readler Dear Chairman Grassley and Ranking Member Feinstein: We, the undersigned 27 national, state and local advocacy organizations, representing the interests of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people and everyone living with HIV, urge you to oppose the nominations of Eric Murphy and Chad Readler to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Almost a million LGBT people live in Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio and Tennessee.1 Consequently, the views of these nominees on the equal dignity of LGBT people and their families are highly relevant to whether LGBT people living in these states will receive fair and impartial justice if these nominees are confirmed to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. The records of these two nominees, particularly with respect to civil rights issues, reflect a deep hostility to the principles of equality, liberty, justice and dignity under the law for LGBT Americans, among others. Accordingly, we do not believe these nominees will provide impartial justice to LGBT people and their families, and therefore urge you to oppose their nominations. Eric Murphy Mr. Murphy’s record demonstrates that he is one of the country’s most vigorous opponents of marriage equality. Following two federal District Court decisions striking down Ohio’s and Michigan’s bans on marriage for same-sex couples,2 Mr. -

19-40016 Document: 00515351760 Page: 1 Date Filed: 03/19/2020

Case: 19-40016 Document: 00515351760 Page: 1 Date Filed: 03/19/2020 No. 19-40016 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. NORMAN VARNER, Defendant-Appellant. On Appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, No. 4:11-cr-00014 ________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC., HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN, NATIONAL CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY, NATIONAL LGBT BAR ASSOCIATION, NATIONAL TRANS BAR ASSOCIATION, AND TRANSGENDER LAW CENTER, IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT- APPELLANT’S PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC ________________________________________________ Ethan Rice Shelly Lynn Skeen Richard Saenz Texas State Bar No. 24010511 LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. EDUCATION FUND, INC. 120 Wall Street, 19th floor 3500 Oak Lawn Avenue, Suite 500 New York, NY 10005 Dallas, TX 75219-722 T: (212) 809-8585 Texas Bar No. 24010511 F: (212) 809-0055 T: (214) 219-8585 [email protected] F: (214) 219-4455 [email protected] [email protected] i Case: 19-40016 Document: 00515351760 Page: 2 Date Filed: 03/19/2020 Sharon McGowan Diana Flynn LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. 1776 K Street, NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20006 T: (202) 804-6245 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae ii Case: 19-40016 Document: 00515351760 Page: 3 Date Filed: 03/19/2020 CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following listed persons and entities as described in the fourth sentence of Rule 28.2.1 have an interest in the outcome of this case. -

Family Equality Council

FAMILY WEEK A very special thank you to the members of our Protectors Circle! We look forward to welcoming current and new members of the Protectors Circle to Clambake. To learn more about joining, please visit www.familyequality.org/protectors. CELEBRATE • COMMIT • CONNECT LETTER from the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR of FAMILY EQUALITY COUNCIL 2 LETTER from the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR of COLAGE 3 FAMILY EQUALITY COUNCIL BOARD & STAFF 4 SPECIAL THANKS 5 INCLUSIVITY STATEMENT 6 EVENT SPONSORS and NATIONAL PARTNERS 7 EVENT SCHEDULE 8 -19 FACILITATOR BIOS 19 MAP of PROVINCETOWN 20 - 21 PROTECTORS CIRCLE 22 - 23 COLAGE PROGRAMMING 24 - 25 FAMILY WEEK 2015 • July 25 - August 1 • Provincetown 1 message from the executive director of family equality council Welcome to the 20th Family Week in Provincetown, MA! It’s hard to comprehend how many advances we’ve seen This year we’ve seen enormous growth in our reach, with since we were last here together. The world is a different programs around the country that serve an ever-growing place, a better place, for our families. Yet so much remains number of families. We launched a legal clinic project in to secure our true legal and lived equality. the South, along with a full slate of programs to support our families in that region; Our public education efforts have This week is a chance to come together, share stories, grown to reach millions of Americans so they can better and make memories. For my family, Family Week is about understand our families and the values we share; And our connecting with other families and it’s also about having policy work has continued to change laws and regulations a moment with a community as dedicated as we are to that directly impact the daily lives of not only the three creating a better world for our families. -

LGBT Newsletter 2002.Qxd

Equal Time LGBT Community Service Fall 2002 Jenner & Block Takes Lawrence Table of Contents to United States Supreme Court Jenner & Block Takes Jenner & Block has teamed up with Lambda which includes Jenner & Block Partners Lawrence to United States Legal Defense & Education Fund to seek United Paul Smith and William Hohengarten Supreme Court 1-2 States Supreme Court review of the constitution- and Associates Daniel Mach and Sharon ality of same-sex sodomy laws: The Firm has McGowan, and Lambda attorneys Ruth Harlow, Championing Causes asked the Supreme Court to review the decision Susan Sommer and Patricia Logue, who is a Facing the Community 2 in Lawrence and Gardner v. Texas, in which two Jenner & Block alumna. men were convicted of “homosexual conduct” First, they argue that the Texas statute, which involving consensual adult sexual intimacy singles out gay men and lesbians for discriminatory New Associate Updates between the men in the privacy of one of their treatment, cannot survive equal protection review ACLU Book on Rights of homes. The Texas law criminalizes only same-sex in light of several Supreme Court decisions LGBT People 3 conduct, not identical conduct by male-female including Romer v. Evans. In Romer, the Supreme couples. Court struck down a Colorado provision that would Firm Alums Move to The case began on Sept. 17, 1998, when sher- have made it more difficult for gay men and les- Public Service 3 iff’s deputies, responding to a false report of an bians than for any other class of people to secure armed intruder, entered John Lawrence’s apart- legislative protections against discrimination. -

Speaker Biographies

Speaker Biographies Ope Adebanjo ’20, Student, Harvard Law School Ope Adebanjo is a second year JD Candidate at Harvard Law School. She graduated from Harvard College in 2015 and majored in Comparative Literature and African Studies, with a minor in Sociology and a citation in Yoruba. Ope worked as an operations supervisor at McMaster-Carr Supply Company in Atlanta GA, managing teams of e-commerce and sales representatives and managing warehouse projects and operations during her time before law school. She also has her Masters in International Business from J. Mack Robinson College of Business at Georgia State University. As a HLS student, Ope is interested in intellectual property law and international business law with a focus on the intersection of policy and technology. Kendra Albert ’16, Clinical Instructional Fellow, Cyberlaw Clinic, Harvard Law School Kendra is a clinical instructional fellow at the Cyberlaw Clinic at Harvard Law School, where they teach students how to practice law by working with pro bono clients. Previously, they were an associate at Zeitgeist Law PC, a boutique technology law firm in San Francisco, and a research associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. Kendra’s scholarship and academic work touches on diverse issues, from online harassment to linkrot to video game preservation. They hold a JD cum laude from Harvard Law School and a bachelor’s degree in lighting design and history from Carnegie Mellon University. Julie Anna Alvarez ’88, Director of Alumni and International Career Services, Columbia Law School Julie Anna Alvarez is the Director of Alumni and International Career Services at Columbia Law School’s Office of Career Services and Professional Development. -

Sexual Contact Newsletter of the Sexual Behavior, Politics, and Communities Division, Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) Summer 2006

Sexual Contact Newsletter of the Sexual Behavior, Politics, and Communities Division, Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) Summer 2006 Diane Notes from the Chair In 1999 Colonel David Schroer a retired Greetings from Macon, where we were Special Forces Officer and expert in Terrorism honored with the appearance of noted Attorney and interviewed for and was offered the position of cable television host Nancy Grace at the March 2006 Counter Terrorism Expert at the United States Library renewal of the noted Cherry Blossom Festival. This of Congress. Prior to beginning the new position will be my final newsletter as Chair of the Sexual David disclosed to his new manager that when he Behavior, Politics, and Communities Division. My began the new position he would no longer be David, closing observations appear in this newsletter. We are but instead would be Diane Schroer. Within 12 hours pleased that Sandra Schroer will assume the esteemed the offer for the position was rescinded. With the help position as Chair at the Division Business Meeting of the ACLU, David (who later became Diane) filed conducted during the upcoming SSSP conference this suit against the Library of Congress in what could summer. Sandra has contributed a description for her prove to be a landmark case in gender discrimination new book. The information appears elsewhere in this and transgender equality. Diane has become a newsletter. spokesperson for transgender equality and participates There are some immediate concerns for the in ongoing discussions and education about issues Sexual Behavior Division. First, we are seeking a faced by people in the transgender population.