Background Checks in the University Admissions Process: an Overview of Legal and Policy Considerations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY PRIDE (4-6, 1-0 CAA) Vs

2003-2004 HOFSTRA WOMEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES – Game 11 HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY PRIDE (4-6, 1-0 CAA) vs. University of North Carolina – Wilmington Seahawks (5-5, 0-1 CAA) Friday, January 9, 2004 – 7 p.m. Hofstra University Arena (5,124) – Hempstead, New York 2003-2004 HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY WOMEN’S BASKETBALL SCHEDULE (4-6, 1-0 CAA) Contact: November Stephen A. Gorchov 8 SAT. SYRACUSE AAU (Exhibition) W 79-76 (516) 463-4933 – Work 23 Sun. at #14 North Carolina L 45-92 25 TUE. QUINNIPIAC W 65-62 (516) 523-5252 - Cell BINGHAMTON TIME WARNER CLASSIC E-mail - [email protected] 29 Sat. at Binghamton L 44-64 30 Sun. vs. Canisius L 74-78 (OT) Radio: WRHU (88.7 FM) and December www.wrhu.org 4 Thu. at Columbia L 62-76 9 Tue. at Rhode Island W 66-61 13 SAT. PRINCETON (Fox Sports New York) W 55-49 Play-by-Play – Ryan Hurley (Break the Attendance Day) Color – Josh Harman FIU SUN & FUN CLASSIC Sideline – Justin Paley 28 Sun. vs. Pepperdine L 50-52 29 Mon. vs. Florida International L 56-80 Hofstra Athletic Homepage: The Hofstra athletic January homepage can be found at www.hofstra.edu/Sports 4 SUN. VIRGINIA COMMONWEALTH * W 75-70 9 FRI. UNC WILMINGTON * 7 P.M. 11 Sun. William & Mary * 2 p.m. HOFSTRA’S TENTATIVE STARTERS 15 Thu. Delaware * 7 p.m. #-Pos Name Cl PPG RPG APG 18 SUN. OLD DOMINION * 2 P.M. (Girl Scout Day) 10-G Cigi McCollin R-Fr. 8.9 2.9 1.4 22 Thu. -

2009 Monarch Baseball

2009 MONARCH BASEBALL Table of Contents Quick Facts Media Information GENERAL INFORMATION Athletic Administration Location: Norfolk, VA. 23529 Interviews: President John R. Broderick (Interim) ....... 24 Enrollment: 23,500 Coach Meyers is available during the week Athletic Director Jim Jarrett ........................ 24 Founded: 1930 as the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary for interviews before and after practice and Athletic Staff Phone Numbers .................... 24 Nickname: Monarchs on game days after the competition. Please Colors: Slate Blue and Silver contact the Sports Information Office at Academic Support ....................................... 25 PMS Colors: 540 Navy Blue; 877 Silver/429 Gray & 283 Lt. Blue Facilities ......................................................... 26 Stadium: Bud Metheny Baseball Complex (2,500) 757‑683‑3372 for more information. Baseball Clinic............................................... 55 Dimensions: LF & RF (325); CF (395); Alleys (375) Photographers: Surface: Natural Grass Only working photographers will be al‑ Bud Metheny Complex Conference: Colonial Athletic Association lowed on the playing field during games. Bud Metheny ................................................ 28 UNIVERSITY PERSONNEL President: John R. Broderick (Interim) Credentials must be secured at least 24 Stadium Records .......................................... 29 Faculty Representative: Dr. Janis Sanchez‑Hucles hours in advance of games. Photographers Coaching Staff Athletic Director: Dr. Jim Jarrett -

South Carolina Baseball Under Ray Tanner

23655_USCBBMG_COVERS.indd 1 1/11/1/11/0707 99:52:56:52:56 AM 23655_USCBBMG_COVERS.indd 2 1/9/07 10:42:47 AM 001-16.indd1-16.indd 1 11/19/07/19/07 111:25:521:25:52 AAMM CAROLINA BASEBALL RECORDS & HISTORY .......................................77 The Road To Omaha ..................................................1 Year-by-Year Results ......................................... 78-79 Table of Contents .......................................................2 Coaching Records ....................................................80 NTENTS Quick Facts ................................................................3 Gamecock Record Book .................................... 81-94 2006 In Review ...................................................... 4-5 Annual Team Statistics .............................................95 F CO 2006 In Review ...................................................... 6-7 NCAA Tournament History ............................... 96-97 South Carolina In The Pros ....................................8-9 Conference Tournament History ........................ 98-99 LE O Sarge Frye Field .......................................................10 Gamecock All-Americans ......................................100 AB Strength & Conditioning ..........................................11 Awards & Honors ...........................................101-103 TABLE OF CONTENTS OF TTABLE 2007 Outlook ..................................................... 12-13 College World Series Teams ...........................104-111 Media Information/Media -

Vs UNC WILMINGTON SEAHAWKS (11-2, 0-0 CAA)

2009 HOFSTRA BASEBALL GAME NOTES – GAME 7-9 HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY PRIDE (0-6, 0-0 CAA) vs UNC WILMINGTON SEAHAWKS (11-2, 0-0 CAA) Friday, March 13 – 4 p.m. Saturday, March 14 – 4 p.m. Sunday, March 15 – 2 p.m. Brooks Field – Wilmington, North Carolina 2009 HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY BASEBALL SCHEDULE Contact: Brian Bohl FEBRUARY 20 Fri. at Florida State L 3-9 Office Phone: (516) 463-2907 21 Sat. at Florida State (DH) L 7-21, 2-3 Fax: (516) 463-5033 22 Sun. at Florida State L 4-10 Cell Phone: (516) 287-0149 27 Fri. at North Carolina State (DH) L, 4-11, 2-15 E-mail: [email protected] MARCH Hofstra Athletic Homepage: www.hofstra.edu/athletics 13 Fri. at UNC Wilmington* 4 p.m. 14 Sat. at UNC Wilmington* 4 p.m. 15 Sun. at UNC Wilmington* 2 p.m. Catch the pre and postgame information online: 18 Wed. ST. JOHN’S 3 p.m. For stats, news and updates, go to 21 Sat. VERMONT (DH) 12 p.m. http://www.hofstra.edu/Athletics/Baseball/index_Baseball.cfm 22 Sun. VERMONT (DH) 12 p.m. 24 Tue. SIENA 3:30 p.m. 27 Fri. NORTHEASTERN* 3 p.m. HOFSTRA ’S TENTATIVE STARTERS 28 Sat. NORTHEASTERN* 2 p.m. 29 Sun. NORTHEASTERN* 1 p.m. Head Coach: Patrick Anderson (Mars Hill College, 1997) W31ILLIAM & MTue.ARY * MANHATTAN 3 p.m. (2009 Stats) Lineup APRIL # Pos. Name Cl. G-GS AVG HR RBI 1 Wed. at Stony Brook 3:30 p.m. 3 Fri. at Virginia Commonwealth* 7 p.m. -

UNCW 2 Game Notes.Qxd

LL AA DD YY MM OO NN AA RR CC HH GG aa mm ee DD aa yy NN oo tt ee ss 2007-08 LADY MONARCH SCHEDULE GAME TWENTY ONE: F e b r u a r y 1 , 2 0 0 8 November............................................................................................................ Ted Constant Convocation Center (8,600) z Norfolk, Va. 10 Sat. (RV/RV) MIDDLE TENNESSEE .W, 76-68 (13/15) Old Dominion Lady Monarchs (17-33, 8-00 CAA) vs. 13 Tue. at East Carolina . .W, 88-66 UNC-WWilmington Seahawks (11-88, 2-66 CAA) 17 Sat. CHARLOTTE . .W, 80-59 PROBABLE STARTERS: PARADISE JAM - St. Thomas, V.I. Pos. No. Name: Cl: Ht: ppg: rpg: Miscellaneous: 23 Fri. vs. No. 2/2 Connecticut . .L, 43-86 F 11 Shahida Williams Sr. 5-11 8.5 5.7 Narrowly missed double-double vs. MTSU 24 Sat. vs. No. 4/4 Stanford . .L, 61-69 F 44 Megan Pym Sr. 6-4 8.7 7.6 Career-high 14 points at William & Mary C 45 Tiffany Green Jr. 6-2 9.4 7.3 Posted three double-doubles 25 Sun. No. 22/20 Purdue . .W, 66-53 G 04 Jazzmin Walters Jr. 5-2 7.1 1.8 Career-high seven rebounds at No. 21/20 Vanderbilt 29 Thu. (RV/RV) PENN STATE . .W, 77-49 G 23 T.J. Jordan Sr. 5-8 13.7 3.2 All-time 3pt. record holder at ODU December.............................................................................................................. OFF THE BENCH: 2 Sun. (20/19) MICHIGAN STATE .W, 79-73 Pos. No. Name: Cl: Ht: ppg: rpg: Miscellaneous: 5 Wed. -

2011-12 USBWA Directory

U.S. BASKETBALL WRITERS ASSOCIATION NCAA DIVISION I SCHOOLS America East ..................................................................americaeast.com Big East ....................................................................................bigeast.org Albany ..............................................................................ualbanysports.com Cincinnati ..............................................................................gobearcats.com Binghamton ..........................................................................bubearcats.com Connecticut ..................................................................... uconnhuskies.com Boston University ....................................................................goterriers.com DePaul .................................................................... depaulbluedemons.com Hartford ........................................................................... hartfordhawks.com Georgetown ...............................................................................guhoyas.com Maine ................................................................................goblackbears.com Louisville .................................................................................uofl sports.com Maryland-Baltimore County ..........................................umbcretrievers.com Marquette .......................................................................... gomarquette.com New Hampshire .................................................................. unhwildcats.com -

University of North Carolina Wilmington Undergraduate Catalogue

Undergrad 07-08 3/26/07 8:27 AM Page 1 University of North Carolina Wilmington Undergraduate Catalogue 2007–2008 Bulletin 58 The University of North Carolina Wilmington is committed to and will provide equality of educa- tional and employment opportunity for all persons regardless of race, sex (such as gender, mari- tal status, and pregnancy), age, color, national origin (including ethnicity), creed, religion, disability, sexual orientation, political affiliation, veteran status or relationship to other university constituents—except where sex, age or ability represent bona fide educational or occupational qualifications or where marital status is a statutorily established eligibility criterion for state- funded employee benefit programs. INFORMATION Admissions (910) 962-3243 http://www.uncw.edu/admissions/ Financial Aid and Veterans Services (910) 962-3177 http://www.uncw.edu/finaid/ Registrar (910) 962-3125 http://www.uncw.edu/reg/ University Operator (910) 962-3000 World Wide Web Home Page: http://www.uncw.edu Undergrad 07-08 3/30/07 1:55 PM Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Greetings from the Chancellor and Board of Trustees Chair . .3 University Calendar . .5 Administrative Officers . .9 The University of North Carolina . .12 University of North Carolina Wilmington . .14 Equal Opportunity, Diversity, and Unlawful Harassment . .20 The Campus . .24 Admissions . .31 Expenses . .39 Financial Aid and Veterans Services . .47 University Regulations . .84 Student Life . .96 Student Support Offices and Services . .110 Academic Programs . .114 Enrichment Courses and Programs . .118 Degree Programs and Requirements . .124 College of Arts and Sciences . .129 Cameron School of Business . .178 Watson School of Education . .186 School of Nursing . .198 Special Academic Programs . -

Norfolk State University Men’S Basketball • Game 6 | Vs

2020-21 Norfolk State University Men’s Basketball • Game 6 | vs. UNC Wilmington (Norfolk, Va./Joseph Echols Hall) For More Information, Contact: Mike Bello, Assistant Sports Information Director/MBB Contact Office Phone: 757.823.2628 Norfolk State Cell Phone: 814.602.6678 Email: [email protected] Website: www.NSUSpartans.com Twitter: @NSUSpartans Facebook: NorfolkStateAthletics University Instagram: @NSUAthletics Mailing Address: NSU Sports Infor- mation Office • 700 Park Ave. • Men’s Basketball Game Notes Norfolk, VA 23504 Norfolk State Spartans (3-2) 2020-21 Norfolk State Schedule Game (3-2 overall, 0-0 MEAC) vs. 6 UNC Wilmington Seahawks (3-3) November Game Information Fri. 27 .......at James Madison ..............W, 83-73 Date/Time: Friday, December 18, 2020 | 4 p.m. Sat. 28 ......vs. Radford .........................W, 57-54 Site: Norfolk, Va. | Joseph Echols Hall (4,500) TV: None Radio: None December Live Stats: NSUSpartans.com/SidearmStats/mbball Wed. 2 ......Old Dominion .....................L, 64-80 Live Video: NSUSpartans.com/Watch Mon. 7 ......Hampton ............................W, 76-64 Series Information: First Meeting Wed. 9 ......William & Mary ............. Postponed Head Coaches: NSU - Robert Jones (128-113, 8th season) Sun. 13 .....at UNC Greensboro .............L, 47-64 UNCW - Takayo Siddle (3-3, 1st season) Dec. 15 .....Regent .......................... Postponed Fri. 18 .......UNCW ....................................4 p.m. Setting the Scene Sat. 26 ......at George Mason .................... 4 p.m. Norfolk State will play its last home game this Friday before the start of MEAC play when the Spartan men’s basketball team hosts UNC Wilmington. Tip-off is set for 4 p.m. at Jo- seph Echols Hall. January Sun. 3 .......Howard * ......................... -

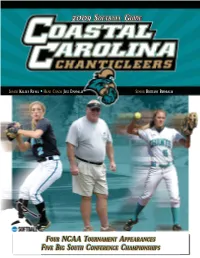

2009 Softball Guide

2009 S OFTBALL G UIDE SENIOR KELSEY R IFFEL • HEAD C OACH J ESS D ANNELLY SENIOR BRITTANY B IRNBAUM FOUR NCAA T OURNAMENT A PPEARANCES FIVE B IG S OUTH C ONFERENCE C HAMPIONSHIPS @ 5 p.m. 5 p.m. 6 p.m. @ 2:30 p.m. 4 p.m. LIMESTONE UNC WILMINGTON SOUTH CAROLINA MICHIGAN STATE NORTH CAROLINA Mecaela Thu.- May 7- Sat. Big South Tournament at 10 Va.) (Radford, TBA Tue. Tue. March 17 Fri. 20 March CHARLESTON SOUTHERN* March Wed. 25 Southern* (DH) Charleston at 2 p.m. April Wed. 4 p.m. 1 Sat. UNC Wilmington at April Sun. 4 April GARDNER- WEBB* (DH) Tue. 5 April GARDNER- WEBB* April Wed. 7 p.m. South Carolina at 2 p.m. 5 8 Sat. April Sun. 11 April (DH) Radford* at 12 April Wed. 1 p.m. 5:30 p.m. Radford* at 15 Sat. College of Charleston at April 18 Sun. April (DH) Presbyterian* at 6 p.m. 19 April Wed. 22 Presbyterian* at 3 p.m. Sat. April 25 Sun. 1 p.m. April WINTHROP* (DH) 26 1 p.m. Fri. WINTHROP* May Sat. p.m. May 1 1 LIBERTY* 2 LIBERTY* (DH) p.m. 2 1 p.m. 1 p.m. 6 p.m. Day Date Sat. March 14 Opponent Time BOLD CAPS Home Games in % 11:30 a.m. % 4:30 p.m. % Kickin’ Chicken Classic (Conway, S.C.) Classic (Conway, % Kickin’ Chicken ^ Jacksonville Tournament (Jacksonville, Fla.) ^ Jacksonville Tournament @ 1:30 p.m. % 2 p.m. % 2 p.m. Alyssa S.C.) (Conway, Softball Tournament Carolina @ Coastal # University of Florida – Lipton Invitational (Gainesville, Fla.) Invitational of Florida – Lipton # University * Big South Conference Game (DH) - Doubleheader * Big South Conference @ 4 p.m. -

2007 Monarch Baseball

2007 MONARCH BASEBALL Table of Contents Quick Facts Media Information Athletic Administration GENERAL INFORMATION Interviews: Location: Norfolk, VA. 23529 President Roseann Runte ............................22 Coach Meyers is available during the week for Enrollment: 21, 500 interviews before and after practice and on game Athletic Director Jim Jarrett ........................22 Founded: 1930 as the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary days after the competition. Please contact the Athletic Staff Phone Numbers ....................22 Nickname: Monarchs Sports Information Offi ce at 757-683-3372 for Support Staff .................................................23 Colors: Slate Blue and Silver more information. Facilities ......................................................... 24 PMS Colors: 540 Navy Blue; 877 Silver/429 Gray & 283 Lt. Blue Baseball Clinic............................................... 55 Stadium: Bud Metheny Baseball Complex (2,500) Photographers: Dimensions: LF & RF (325); CF (395); Alleys (375) Only working photographers will be allowed on Bud Metheny Complex Surface: Natural Grass the playing fi eld during games. Credentials must Bud Metheny ................................................ 26 Conference: Colonial Athletic Association be secured at least 24 hours in advance of games. Stadium Records .......................................... 27 UNIVERSITY PERSONNEL Photographers will be asked to wear a press photo President: Dr. Roseann Runte (SUNY New Paltz ’68) pass at all times when shooting. Coaching -

Meet the Lady Chanticleers C #1#1 Megan #9 Kristinkristi N O Bickford Cozzens Freshman, 6-1 Freshman, 5-9 Middle Blocker Setter a Olathe, Kan

Meet The Lady Chanticleers C #1#1 Megan #9 KristinKristi n o Bickford Cozzens Freshman, 6-1 Freshman, 5-9 Middle Blocker Setter a Olathe, Kan. Vincent, Ohio s Olathe South Warren t High School: Three-year letterwinner... Served as team captain... High School: Three-year letterwinner... School record holder Helped team to the Kansas State Championship as a junior and for most sets in one match (40)... Helped high school team to a then a third place S nish her senior year... As a senior, named three league championships... Two-time All-League honoree... First-Team All-State, First-Team All-State Tournament Team, All-District selection as a senior... Named District 13 Senior of the 2006 Sun T ower MVP, All-League, All-Metro, All-Olathe, All-Sun. Year... Participated in the State All-Star game... Marietta Times l .. Also lettered in basketball and softball... Personal: Full name Female Athlete of the Year... Three-time letterwinner in basketball Megan Kathryn Bickford... Born December 5, 1988...Daughter and four-time letterwinner in track... Garnered All-Academic honors of Brice and Kristi Bickford... Mom Kristi played volleyball at Fort in volleyball, basketball, and track... Personal: Full name: Kristin Hays State University, while Dad Brice played football... Brother Nicole Cozzens... Daughter of Scott and Shawna Cozzens... Austen played baseball at Fort Hays State... Majoring in recreation Majoring in chemistry. C and sport management. Off The Court With Megan Bickford Off The Court With Kristin Cozzens Reality show I would be on: Top Chef Favorite musician/group: Rascal Flatts a Best movie on a road trip: How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days Favorite sport to watch aside from volleyball: Basketball Favorite junk food: Starburst One thing always carry: my phone r Favorite sport to watch aside from volleyball: Basketball People have said I look like: Katie Holmes TV show I watch religiously: Grey’s Anatomy TV show I watch religiously: The Hills o #4 Chelsy #8 Amanda l Kimes Russell Freshman, 5-9 Freshman, 5-10 i Outside Hitter Outside Hitter/ Munster, Ind. -

Campus Communique for Cabinet Notes

UNCW A PUBLICATION FOR UNIVERSITY FACULTY AND STAFF University Advancement Patsy Larrick, Editor VOLUME XXI, NUMBER 1 JULY 11, 1991 Lady swimmers recognized: The Nation- CaHILL to leave POST: Dr. Charles L. il Collegiate Athletic Association has notified Cahill, provost and vice chancellor for Academic UNCW that the Women's Swimming Team Affairs for 21 years, will step down as UNCWs top registered the fourth highest team grade point academic officer at the end of the 1991-92 average among NCAA Division I Schools during academic year. Cahill plans to return to the class- he 1990 fall semester. Coach Dave Allen's women room as a professor of chemistry. A national 30sted a 3.100 cumulative GPA in the College search will be conducted for his successor. Chan- Swimming Coaches Association of America Study cellor Leutze expects to cumounce the formation of earning the team an "Excellent" rating. The a search committee this fall. Seahawks ranked fourth best nationally in the class- Deadlines: Performance reviews on SPA room behind Purdue (3.260), Ohio (3.020), and employees for last year are due in Human Resour- \uburn (3.010). UNC-CH, the only other school in ces by August 1. Workplans are due September 1. :he NC state system included in the report, placed New workplan forms will be mailed around July 15. I8th with a team average of 2.890. Congratulations ladies on your success both in the classroom and NOAA GRANT: UNCW has received a $2.38 mil- in the pool! lion grant from the National Oceanic and Atmos- pheric Administration to continue the scientific HaRKIN RECEPTION: Faculty and staff are in- work of the National Undersea Research Center at cited to a reception in honor of Dr.