Requires Subscription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helsingin Sosiaalivirasto

Itäinen Helsinki Sisältö SOSIAALIVIRASTON PALVELUT .................................. 3 Itäinen sosiaali- ja lähityön yksikkö ............................... 3 Sosiaalityö ................................................................. 4 Lähityö ....................................................................... 4 Omaishoidon tuki ....................................................... 5 Itäinen omaishoidon toimintakeskus .......................... 5 Vanhusten palvelu- ja virkistyskeskukset ..................... 6 Päivätoiminta ................................................................ 7 Palveluasuminen ja ympärivuorokautinen hoito ........... 7 Vammaispalvelut .......................................................... 8 Kuljetuspalvelut ............................................................ 9 Asunnon muutostyöt ................................................... 10 Toimiva Koti ................................................................ 11 Toimeentulotuki .......................................................... 11 TERVEYSKESKUKSEN PALVELUT ............................ 12 Terveysasemat ........................................................... 12 Päivystys .................................................................... 14 Laboratoriot ................................................................ 15 Omahoitotarvikejakelu ................................................ 15 Hammashoitolat ......................................................... 16 Kotihoito .................................................................... -

Helsinki Alueittain 2015 Helsingfors Områdesvis Helsinki by District

Helsingfors stads faktacentral City of Helsinki Urban Facts HELSINKI ALUEITTAIN Helsingfors områdesvis 2015 Helsinki by District Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus PL 5500, 00099 Helsingin kaupunki, p. 09 310 1612 Helsingfors stads faktacentral PB 5500, 00099 Helsingfors stad, tel. 09 310 1612 City of Helsinki Urban Facts P.O.Box 5500, FI-00099 City of Helsinki, tel. +358 9 310 1612 www.hel.fi/tietokeskus Tilaukset / jakelu p. 09 310 36293 Käteismyynti Tietokeskuksen kirjasto, Siltasaarenk. 18-20 A Beställningar / distribution tel. 09 310 36293 Direktförsäljning Faktacentralens bibliotek, Broholmsgatan 18-20 A Orders / distribution tel. +358 9 310 36293 Direct sales Library, Siltasaarenkatu 18-20 A S-posti / e-mail [email protected] HELSINKI ALUEITTAIN Helsingfors områdesvis 2015 Helsinki by District Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus Helsingfors stads faktacentral Helsinki City of Helsinki Urban Facts Helsingfors 2016 Julkaisun toimitus Tea Tikkanen Redigering Editors Käännökset Magnus Gräsbeck Översättningar Translations Taitto Petri Berglund Ombrytning General layout Kansi Tarja Sundström-Alku Pärm Cover Tekninen toteutus Otto Burman Tekniskt utförande Tea Tikkanen Technical Editing Pekka Vuori Valokuvat Kansi - Pärm - Cover: Helsingin kaupungin matkailu- ja kongressitoimiston Foton materiaalipankki / Lauri Rotko, Visit Helsinki / Jussi Hellsten Photos Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus / Raimo Riski Kartat Pohja-aineistot: Kartor © Helsingin kaupunkimittausosasto, alueen kunnat ja HSY, 2014 Maps © Liikennevirasto / Digiroad 2014 -

Examples and Progress in Geodata Science Final Report of Msc Course at the Department of Geosciences and Geography, University of Helsinki, Spring 2020

DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES AND GEOGRAPHY C19 Examples and progress in geodata science Final report of MSc course at the Department of Geosciences and Geography, University of Helsinki, spring 2020 MUUKKONEN, P. (Ed.) Examples and progress in geodata science: Final report of MSc course at the Department of Geosciences and Geography, University of Helsinki, spring 2020 EDITOR: PETTERI MUUKKONEN DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES AND GEOGRAPHY C1 9 / HELSINKI 20 20 Publisher: Department of Geosciences and Geography Faculty of Science P.O. Box 64, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Journal: Department of Geosciences and Geography C19 ISSN-L 1798-7938 ISBN 978-951-51-4938-1 (PDF) http://helda.helsinki.fi/ Helsinki 2020 Muukkonen, P. (Ed.): Examples and progress in geodata science. Department of Geosciences and Geography C19. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. Table of contents Editor's preface Muukkonen, P. Examples and progress in geodata science 1–2 Chapter I Aagesen H., Levlin, A., Ojansuu, S., Redding A., Muukkonen, P. & Järv, O. Using Twitter data to evaluate tourism in Finland –A comparison with official statistics 3–16 Chapter II Charlier, V., Neimry, V. & Muukkonen, P. Epidemics and Geographical Information System: Case of the Coronavirus disease 2019 17–25 Chapter III Heittola, S., Koivisto, S., Ehnström, E. & Muukkonen, P. Combining Helsinki Region Travel Time Matrix with Lipas-database to analyse accessibility of sports facilities 26–38 Chapter IV Laaksonen, I., Lammassaari, V., Torkko, J., Paarlahti, A. & Muukkonen, P. Geographical applications in virtual reality 39–45 Chapter V Ruohio, P., Stevenson, R., Muukkonen, P. & Aalto, J. Compiling a tundra plant species data set 46–52 Chapter VI Perola, E., Todorovic, S., Muukkonen, P. -

NEW-BUILD GENTRIFICATION in HELSINKI Anna Kajosaari

Master's Thesis Regional Studies Urban Geography NEW-BUILD GENTRIFICATION IN HELSINKI Anna Kajosaari 2015 Supervisor: Michael Gentile UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI FACULTY OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES AND GEOGRAPHY GEOGRAPHY PL 64 (Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto Faculty Department Faculty of Science Department of Geosciences and Geography Author Anna Kajosaari Title New-build gentrification in Helsinki Subject Regional Studies Level Month and year Number of pages (including appendices) Master's thesis December 2015 126 pages Abstract This master's thesis discusses the applicability of the concept of new-build gentrification in the context of Helsinki. The aim is to offer new ways to structure the framework of socio-economic change in Helsinki through this theoretical perspective and to explore the suitability of the concept of new-build gentrification in a context where the construction of new housing is under strict municipal regulations. The conceptual understanding of gentrification has expanded since the term's coinage, and has been enlarged to encompass a variety of new actors, causalities and both physical and social outcomes. New-build gentrification on its behalf is one of the manifestations of the current, third-wave gentrification. Over the upcoming years Helsinki is expected to face growth varying from moderate to rapid increase of the population. The last decade has been characterized by the planning of extensive residential areas in the immediate vicinity of the Helsinki CBD and the seaside due to the relocation of inner city cargo shipping. Accompanied with characteristics of local housing policy and existing housing stock, these developments form the framework where the prerequisites for the existence of new-build gentrification are discussed. -

Master's Thesis Geography Geoinformatics

TypeUnitOrDepartmentHere TypeYourNameHere Master’s Thesis Geography Geoinformatics CLUSTERING OF IMMIGRATION POPULATION IN HELSINKI METROPOLITAN AREA, FINLAND: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXPLORATORY SPATIAL DATA ANALYSIS METHODS Vladimir Kekez 2015 Supervisor: Senior lecturer Mika Siljander UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES AND GEOGRAPHY DIVISION OF GEOGRAPHY PL 64 (Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO – HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET – UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty/Section Laitos – Institution – Department Tekijä – Författare – Author Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Avainsanat – Nyckelord – Keywords Säilytyspaikka – Förvaringställe – Where deposited Muita tietoja – Övriga uppgifter – Additional information TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................... iv SYMBOLS ....................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... x 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... -

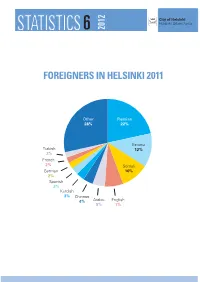

Statistics6 2012

STATISTICS6 2012 FOREIGNERS IN HELSINKI 2011 Other Russian 28% 22% Estonia Turkish 12% 2% French 2% Somali German 10% 2% Spanish 3% Kurdish 3% Chinese 4% Arabic English 5% 7% Contents 1. Foreigners in Helsinki ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Foreigner groups ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Mother tongues of foreign-language residents .................................................................................. 4 2.2 Nationalities of foreigners ................................................................................................................... 5 3. Population of foreign-language speakers by sex and age ......................................................................... 6 4. Spatial distribution of foreign-language residents in Helsinki ................................................................... 7 5. Trends in numbers of foreign-language residents .................................................................................... 7 6. Projection for the foreign-language population ........................................................................................ 9 7. Migration to or from Helsinki among foreign-language residents .......................................................... 10 7.1 Foreign migration between Helsinki and foreign countries ............................................................. -

ONT Turpeinen Timo.Pdf (2.387Mt)

Paikallisen turvallisuustilanteen nykytilan ar- viointi Turpeinen, Timo 2010 Leppävaara Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Laurea Leppävaara Paikallisen turvallisuustilanteen nykytilan arviointi Timo Turpeinen Turvallisuusalan koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Toukokuu 2010 Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu Tiivistelmä Laurea Leppävaara Turvallisuusalan koulutusohjelma Timo Turpeinen Paikallisen turvallisuustilanteen nykytilan arviointi Vuosi 2010 Sivumäärä 56 Opinnäytetyöni käsittelee paikallisen turvallisuustilanteen arviointia paikallisessa turvallisuus- suunnittelussa. Työ jakautuu kahteen osaan, joista ensimmäisessä kuvataan Helsingin kaupun- gin Vuosaaren peruspiirissä tehty turvallisuustilanteen arviointi tai turvallisuuskartoitus. Työn toisessa osassa pohditaan tehdyn kartoituksen ja paikallisen turvallisuussuunnittelun teorian avulla saatua kuvaa paikallisen turvallisuustilanteen arvioinnista ja sitä, mitkä tekijät vaikut- tavat paikallisen turvallisuussuunnittelun tueksi tuotettavan tiedon muodostamiseen. Vuonna 2007 Itäkeskuksen poliisipiirin alueella käynnistetty uuden lähipoliisimallin pilottihan- ke ja siitä saadut myönteiset kokemukset käynnistivät alueella paikallisen turvallisuussuunnit- telun harjoittamisen. Eri viranomaisten keskinäisen yhteistyön perinteestä käynnistynyt tur- vallisuusyhteistyö sai ensimmäisen valtakunnallisen mallinsa vuoden 1999 Turvallisuustalkoot – rikostorjunnan periaateohjelmassa. Turvallisuustalkoista alkanut, systemaattisuuteen ja laa- ja-alaiseen turvallisuuden hallintaan tähtäävä turvallisuusyhteistyö ja sitä -

Esite Helsingin Charlotta 20190418

HELSINGIN CHARLOTTA Tankovainio, Mellunkylä, Helsinki Tankomäenkatu 4 Helmi kodiksi. HELSINGIN CHARLOTTA HELSINGIN CHARLOTTA Helsingin Charlotta Tässä kodissa yhdistyvät modernin kaupunkiasumisen parhaat puolet! Helsingin Charlotta nousee Mellunkylään, Tankovainion alueelle. Uudesta Yrjö ja Hanna ASO-Kodista löytyy viihtyisiä koteja yksin ja kaksin asuville ja pienille perheille. Helsingin Charlottan rakennuttaa ja omistaa Luonto, monipuoliset mahdollisuudet ulkoiluun Yrjö ja Hanna -konserniin kuuluva Asoasunnot sekä erinomaiset liikenneyhteydet tekevät asumi- Uusimaa Oy. Kohteen rakentaa Jalon Uusimaa sesta mutkatonta ja mukavaa. Oy ja sen on suunnitellut Arkkitehtitoimisto Ilkka Laitinen Oy. Helsingin Charlotta on yksi Harvassa kohteessa metsäinen luonto, meren moderneista Helsinki-kerrostaloista, jonka malli läheisyys ja kaupunkimainen asuminen yhdistyvät on valittu asuinalueiden täydennysrakentami- kuten Helsingin Charlottassa. seen Helsingissä. Mustavuoren metsät tarjoavat monipuoliset Koti Helsingin Charlottassa on löytö jokaiselle mahdollisuudet ulkoiluun. Fallbackan viljelypalstat viihtyisää ja valoisaa kaupunkikotia arvostavalle. ilahduttavat viherpeukaloita kivenheiton päässä. Helsingin Charlottan arvioitu valmistumisaika on touko-kesäkuu 2020. Hae mukaan Helsingin Charlottan tarinaan! www.aso-kodit.fi/helsingin-charlotta 2 Helsingin Charlotta | Tankomäenkatu 4 | 00950 Helsinki Helsingin Charlotta – Helmi kodiksi. 3 VIIHTYISÄÄ KAUPUNKIASUMISTA VIIHTYISÄÄ KAUPUNKIASUMISTA NURMIJÄRVI TUUSULA KERAVA TUSBY KERVO Riipilä Ripuby Korso -

Helsingin Ja Helsingin Seudun Väestöennuste 2013–2050

HELSINGIN JA HELSINGIN SEUDUN VÄESTÖENNUSTE 2013–2050 Ennuste alueittain 2013–2022 31 2012 STOJA " TIL Ti31_12.indd 1 4.10.2012 10:11:16 TIEDUSTELUT PUHELIN FÖRFÄGNINGAR TELEFON INQUIRIES TELEPHONE Pekka Vuori, p. – tel. 09 310 36300 09 310 1612 [email protected] Petri Berglund, p. – tel. 09 310 36395 INTERNET [email protected] WWW.HEL.FI/TIETOKESKUS/ JULKAISIJA TILAUKSET, JAKELU UTGIVARE BESTÄLLNINGAR, DISTRIBUTION PUBLISHER ORDERS, DISTRIBUTION Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus p. – tel. 09 310 36293 Helsingfors stads faktacentral [email protected] City of Helsinki Urban Facts KÄTEISMYYNTI OSOITE DIREKTFÖRSÄLJNING ADRESS DIRECT SALES ADDRESS Tietokeskuksen kirjasto PL 5500, 00099 Helsingin kaupunki Siltasaarenkatu 18-20 A, p. 09 310 36377 (Siltasaarenkatu 18-20 A) Faktacentralens bibliotek PB 5500, 00099 Helsingfors stad Broholmsgatan 18-20 A, tel. 09 310 36377 (Broholmsgatan 18-20 A) City of Helsinki Urban Facts Library P.O.Box 5500, FI-00099 City of Helsinki Siltasaarenkatu 18-20 A, tel. +358 09 310 36377 Finland (Siltasaarenkatu 18-20 A9 [email protected] Ti31_12.indd 2 4.10.2012 10:11:18 HELSINGIN JA HELSINGIN SEUDUN VÄESTÖENNUSTE 2013–2050 Ennuste alueittain 2013–2022 BEFOLKNINGSPROGNOS FÖR HELSINGFORS OCH HELSINGFORSREGIONEN 2013–2050 Prognosen områdesvis 2013–2022 TILASTOJA STATISTIK 2012:31 STATISTICS Ti31_12.indd 1 4.10.2012 10:30:35 KÄÄNNÖKSET ÖVERSÄTTNING Magnus Gräsbeck KUVIOT FIGURER Pekka Vuori & Petri Berglund TAITTO OMBRYTTNING Petri Berglund KANSI PÄRM Tarja Sundström-Alku Kansikuva | -

Sovellettavat Tonttien Enimmäishinnat Pääkaupunkiseudulla Vuonna 2021 Huom! Taulukon Hintoihin Liittyvät Soveltamisohjeet* Voivat Korottaa Enimmäishintaa Mm

Valtion tukemassa asuntotuotannossa (pitkä korkotuki) sovellettavat tonttien enimmäishinnat pääkaupunkiseudulla vuonna 2021 Huom! Taulukon hintoihin liittyvät soveltamisohjeet* voivat korottaa enimmäishintaa mm. jos tontti sijaitsee nykyisessä tai tulevassa keskuksessa hyvällä paikalla, esimerkiksi hyvien julkisten tai kaupallisten palvelujen tai esimerkiksi rautatie- tai metroaseman läheisyydessä (maksimietäisyys 1 000 m), voidaan tontin enimmäishintaa korottaa enintään 15 prosenttia. *Vuoden 2021 ARA-enimmäishintoja tarkentavista soveltamisohjeista on päätetty tonttihintapäätöksen 17.12.2020 yhteydessä TH = Tapauskohtainen hinnoittelu eli kyseisillä alueilla hinnat sovitaan ARAn kanssa tapauskohtaisesti Kaupungin osa-alueen nimi (Espoo pienalueet, Helsinki osa-alueet, Kauniainen koko kunta, Kerrostalotontin Pientalotontin Koodi kartalla Kuntanumero Kunta Vantaa kaupunginosat) enimmäishinta (€/kem²) enimmäishinta (€/kem²) 049_001 049 Espoo EESTINMALMI TH TH 049_002 049 Espoo ESPOONKARTANO 310 388 049_003 049 Espoo ESPOONLAHDEN KESKUS TH TH 049_004 049 Espoo ETELÄ-LEPPÄVAARA TH TH 049_005 049 Espoo FRIISILÄ TH TH 049_006 049 Espoo GUMBÖLE 327 409 049_007 049 Espoo HANNUS TH TH 049_008 049 Espoo HANNUSJÄRVI TH TH 049_009 049 Espoo HAUKILAHTI TH TH 049_010 049 Espoo HENTTAA TH TH 049_011 049 Espoo HÖGNÄS 302 378 049_012 049 Espoo IIVISNIEMI TH TH 049_013 049 Espoo JUPPERI 386 483 049_014 049 Espoo JÄRVENPERÄ 330 413 049_015 049 Espoo KALAJÄRVI 288 360 049_016 049 Espoo KARAKALLIO 438 548 049_017 049 Espoo KARHUSUO 273 341 049_018 049 Espoo -

Attractiveness of Different Districts in Helsinki: Segregation in Terms of Poor Financial and Educational Status of the Residents

Attractiveness of Different Districts in Helsinki: Segregation in Terms of Poor Financial and Educational Status of the Residents Linda Anttila, Topi Korpela, Saskia Lammi, Laura Pääkkönen and Ilkka Tani Department of Real Estate, Planning and Geoinformatics School of Engineering Aalto University 00076 Aalto [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. The aim of this research is to study attractiveness of different districts in Helsinki. The research tries to find out if there are differences, and on the other hand, similarities between different districts in Helsinki if the financial and educational status of the residents are compared. The main research question is; are there some districts in Helsinki that have a risk to segregate in terms of poor financial and educational status of the residents? Previous researches related to this topic were mainly related to either educational segregation or economic segregation but there is a lack of researches which concentrate on the both aspects at the same time, and take also bad credit history into consideration. This study is based on three different open data sets, two datasets from Paavo and one from Suomen Asiakastieto. In order to find out if there is segregation based on the average income, education level and bad credit history we use clustering analysis and especially dendrograms to analyze the data. In this study dendrograms are used for hierarchical cluster analysis. All of the dendrograms are created in IBM SPSS Statistics 22 -program. The results derived from two dendrograms and a proximity matrix created indicate that in general all of the areas in Helsinki are quite similar with each other.