The Process of Appropriation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.5 Mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System

4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. Technique Guide Table of Contents Introduction 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates 2 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System 4 AO Principles 5 Indications 6 Surgical Technique Preparation 7 Reduce Articular Surface 11 Insert Plate 12 Insert Screw in Central Plate Head Hole 20 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screw 20 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screw 23 Insert Screws in Surrounding Plate Head Holes 26 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 26 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 30 Insert Screws in Plate Shaft 32 Option A: 4.5 mm Cortex Screws 32 Option B: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 34 Option C: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 37 Remove Instruments 40 Product Information Implants 41 Instruments 43 Set Lists 45 Image intensifier control 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate Technique Guide Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. The Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate is part of the VA-LCP Periarticular Plating System which merges variable angle locking screw technology with conventional plating techniques. The 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System has many similarities to standard locking fixation methods, with a few important improvements. Variable angle locking screws provide the ability to create a fixed-angle construct while also allowing the surgeon the freedom to choose the screw trajectory before “fixing” the angle of the screw. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA Doctrina Christiana

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Medieval and Byzantine Studies School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Timothy A. Kearns Washington, D.C. 2014 Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana Timothy A. Kearns, Ph.D. Director: Timothy B. Noone, Ph.D. In the twentieth century, Augustinian scholars were unable to agree on what precisely the De doctrina christiana is about as a work. This dissertation is an attempt to answer that question. I have here employed primarily close reading of the text itself but I have also made extensive efforts to detail the intellectual and social context of Augustine’s work, something that has not been done before for this book. Additionally, I have put to use the theory of textuality as developed by Jorge Gracia. My main conclusions are three: 1. Augustine intends to show how all learned disciplines are subordinated to the study of scripture and how that study of scripture is itself ordered to love. 2. But in what way is that study of scripture ordered to love? It is ordered to love because by means of such study exegetes can make progress toward wisdom for themselves and help their audiences do the same. 3. Exegetes grow in wisdom through such study because the scriptures require them to question themselves and their own values and habits and the values and habits of their culture both by means of what the scriptures directly teach and by how readers should (according to Augustine) go about reading them; a person’s questioning of him or herself is moral inquiry, and moral inquiry rightly carried out builds up love of God and neighbor in the inquirer by reforming those habits and values out of line with the teachings of Christ. -

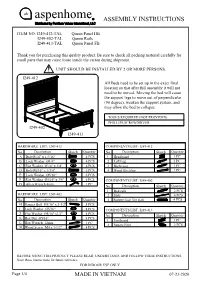

Aspenhome R ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS

ah aspenhome R ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS ITEM NO: I249-412-TAL Queen Panel HB I249-402-TAL Queen Rails I249-413-TAL Queen Panel FB Thank you for purchasing this quality product. Be sure to check all packing material carefully for small parts that may come loose inside the carton during shipment. UNIT SHOULD BE INSTALLED BY 2 OR MORE PERSONS. I249-412 All Beds need to be set up in the exact final location so that after full assembly it will not need to be moved. Moving the bed will cause the support legs to move out of perpendicular (90 degree), weaken the support system, and may allow the bed to collapse. TOOLS REQUIRED (NOT PROVIDED) PHILLIPS SCREWDRIVER I249-402 I249-413 HARDWARE LIST: I249-412 COMPONENTS LIST: I249-412 No. Description Sketch Quantity No. Description Sketch Quantity A Bolt Ø1/4" x 1-9/16" 4 PCS 1 Headboard 1 PC B Lock Washer Ø1/4" 4 PCS 2 Left Leg 1 PC C Flat Washer Ø1/4" x 3/4" 4 PCS 3 Right Leg 1 PC D Bolt Ø5/16" x 1-3/4" 6 PCS 4 Wood Stretcher 1 PC E Lock Washer Ø5/16" 6 PCS F Flat Washer Ø5/16" x 3/4" 6 PCS COMPONENTS LIST: I249-402 G Allen Wrench 4mm 1 PC No. Description Sketch Quantity 1 Bed rails 2 PCS HARDWARE LIST: I249-402 2 Slats 4 PCS No. Description Sketch Quantity 3 Support Leg (for slat) 4 PCS H Hanger Bolt Ø5/16" x 3-1/2" 8 PCS I Lock Washer Ø5/16" 8 PCS COMPONENTS LIST: I249-413 J Flat Washer Ø5/16" x1/2" 8 PCS No. -

The Ruin of the Roman Empire

7888888888889 u o u o u o u THE o u Ruin o u OF THE o u Roman o u o u EMPIRE o u o u o u o u jamesj . o’donnell o u o u o u o u o u o u o hjjjjjjjjjjjk This is Ann’s book contents Preface iv Overture 1 part i s theoderic’s world 1. Rome in 500: Looking Backward 47 2. The World That Might Have Been 107 part ii s justinian’s world 3. Being Justinian 177 4. Opportunities Lost 229 5. Wars Worse Than Civil 247 part iii s gregory’s world 6. Learning to Live Again 303 7. Constantinople Deflated: The Debris of Empire 342 8. The Last Consul 364 Epilogue 385 List of Roman Emperors 395 Notes 397 Further Reading 409 Credits and Permissions 411 Index 413 About the Author Other Books by James J. O’ Donnell Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher preface An American soldier posted in Anbar province during the twilight war over the remains of Saddam’s Mesopotamian kingdom might have been surprised to learn he was defending the westernmost frontiers of the an- cient Persian empire against raiders, smugglers, and worse coming from the eastern reaches of the ancient Roman empire. This painful recycling of history should make him—and us—want to know what unhealable wound, what recurrent pathology, what cause too deep for journalists and politicians to discern draws men and women to their deaths again and again in such a place. The history of Rome, as has often been true in the past, has much to teach us. -

Download This PDF File

Athens between East and West: Athenian Elite Self-Presentation and the Durability of Traditional Cult in Late Antiquity Edward Watts T IS GENERALLY ACCEPTED that the urban centers of the Greek-speaking east more quickly dismantled traditional religious infrastructure and disrupted traditional religious I 1 customs than did cities in the west. The city of Athens, how- ever, has always fit awkwardly in this narrative. Alexandria, long Athens’ rival for cultural supremacy in the Greek world, saw its urban infrastructure violently and effectively Christian- ized in the early 390s by the campaigns and construction projects of the bishop Theophilus.2 Alexandria’s civic and political life arguably followed suit after the violence that accompanied the consolidation of episcopal power by Theo- philus’ successor Cyril and the murder of the philosopher Hypatia in the early 410s.3 Antioch and its hinterland saw its pagan institutions disrupted gradually, first through isolated incidents like the conversion (and ultimate destruction) of the 1 See, among others, C. P. Jones, Between Pagan and Christian (Cambridge [Mass.] 2014) 107–143. 2 J. Hahn, “The Conversion of Cult Statues: The Destruction of the Serapeum 392 A.D. and the Transformation of Alexandria into the ‘Christ- Loving’ City,” in J. Hahn et al. (eds.), From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity (Leiden 2008) 335–363. Cf. E. Watts, Riot in Alexandria (Berkeley 2010) 191–205. 3 On Hypatia see C. Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity (Baltimore 1997) 295–316; M. Dzielska, Hypatia of Alexandria (Cambridge [Mass.] 1995) 88– 93; E. Watts, Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher (Oxford 2017). -

Swivel Drawbar Eyes 405 Swivel Slack Reducing Eye 405L & 405S with 416 Locknut & 208 Snap Ring: 6 15/16

Swivel Drawbar Eyes 405 Swivel Slack Reducing Eye 405L & 405S with 416 Locknut & 208 Snap Ring: 6 15/16 See pages for Front End Assemblies� A 3 B Parts Included: - 375 Bolt - 375A Locknut 2 3/8 5 3/4 2 - 400 Shoe A A - 208 Snap Ring (405L & 405S) - 416 Locknut (405L & 405S) 405 - 422 Sleeve Nut (405SE) - 525 Jam Nut - Pushrod (see below) 1 11/16 4 1/4 SPECIFICATIONS 1 3/4 Maximum Gross Trailer Weight: 90,000 lbs� (40,823 kg) Maximum Tongue Weight: 3,700 lbs� (1,678 kg) 405SE with 422 Sleeve Nut: Inside Diameter: See drawing 6 15/16 1 11/16 MIN 2 15/16 MIN Unit Weight: See chart 2 1/4 MAX 3 1/2 MAX A 3 B Model A B Weight 405L 9 1/4 in� (235 mm) 3 1/8 in� (79 mm) 27�8 lbs� (12�6 kg) 2 3/8 5 3/4 2 405S 8 1/8 in� (206 mm) 2 1/2 in� (64 mm) 26�9 lbs� (12�2 kg) A A 405SE 10 1/8 in� (257 mm) 2 1/4 in� (57 mm) 28�5 lbs� (12�9 kg) 3/4-16UNF-2A 2-12UNF-2A 405 (2 1/2 LONG) 405 Swivel Drawbar Eye: 405 Pushrod Options Standard Pushrod Lengths: - 405L: 415A Pushrod - 17 1/4 in� (438 mm), right-hand thread Optional Left-Hand Threaded Pushrods: - 405S: 415 Pushrod - 15 1/2 in� (394 mm), right-hand thread - 415L: 15 1/2 in� (394 mm), left-hand thread - 405SE: 415A Pushrod - 17 1/4 in� (438 mm), right-hand thread - 415AL: 17 1/4 in� (438 mm), left-hand thread 410L & 410S with 416 Locknut & 208 Snap Ring: 410 Swivel Slack Reducing Eye 1 13/16 A 3 See pages for Front End Assemblies� 2 Parts Included: A A - 411 Shoe 2-12UNF-2A 3/4-16UNF-2A - 208 Snap Ring (410L & 410S) (2 1/2 LONG) - 416 Locknut (410L & 410S) 2 13/16 - 422 Sleeve Nut (410SE) - Pushrod (see -

Missing Final Grade Sheets: 1710

MISSING FINAL GRADES 05/05/2020 02:26 PM Total Sheets Incomplete: 573 Total Blank: 3907 Total N: 6 N Grand Total 1710 Total 1710 Total ALHG 4 4 0 0 4 DIV 13 13 0 0 13 EGRP 30 30 6 6 36 FUQ 424 424 0 0 424 GRAD 793 793 0 0 793 INTR 27 27 0 0 27 INTU 4 4 0 0 4 KGRD 2 2 0 0 2 LAW 4 4 0 0 4 MED 1 1 0 0 1 NBSN 2 2 0 0 2 NSOE 228 228 0 0 228 NURS 38 38 0 0 38 PPS 47 47 0 0 47 UGRD 2290 2290 0 0 2290 Total 3907 3907 6 6 3913 MISSING FINAL GRADE SHEETS: 1710 AAAS No. of classes: 6 Total Blank/N Grades: 73 Total Blank Grades N Grades Difference/Grades In Comb Sect ID AAAS 331 01 8535 58 58 0 0 Douthit,Patrick 0496 DURHAM Cross Lists: VMS 230 01 AAAS 335 01 8538 64 5 0 59 Douthit,Patrick 0497 DURHAM Cross Lists: CULANTH 335 01 MUSIC 335 01 VMS 337 01 ENGLISH 381 01 AAAS 490S 01 5668 3 2 0 1 Aidoo,Lamonte 0432 DURHAM Cross Lists: ROMST 490S 01 CULANTH 490S 01 LATAMER 490S 01 AAAS 496 01 11271 1 1 0 0 Royal,Charmaine D DURHAM AAAS 512S 01 8543 2 2 0 0 Matory,James Lorand 0499 DURHAM Cross Lists: CULANTH 511S 01 RELIGION 511S 01 AAAS 660 01 8549 6 5 0 1 Royal,Charmaine D 0501 DURHAM Cross Lists: CULANTH 660 01 GLHLTH 672 01 ACCOUNTG No. -

THE NATURE of NOMADIC POWER Contacts Between the Huns and the Romans During the Fourth and Fifth Centuries

TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SARJA - SER. B OSA - TOM. 373 HUMANIORA THE NATURE OF NOMADIC POWER Contacts between the Huns and the Romans during the Fourth and Fifth Centuries by Päivi Kuosmanen TURUN YLIOPISTO UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Turku 2013 From the Faculty of Humanities Department of General History University of Turku Finland Supervised by: Professor Auvo Kostiainen Department of General History University of Turku Finland Reviewed by: Professor Auvo Kostiainen Department of General History University of Turku Finland Dr. Docent Katariina Mustakallio Department of History University of Tampere Finland Dr. Thomas Brüggemann Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg Germany Opponent: Dr. Thomas Brüggemann Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg Germany The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. ISBN 978-951-29-5586-2 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-5587-9 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 Painosalama Oy – Turku, Finland 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. Overview to the Research 1 1.2. Previous Research 3 1.3. The Aim of the Research 5 1.4. The Methodology 7 1.5. Central Concepts of the Research 11 1.6. Primary Sources 18 1.7. Structure of the Work 21 2. ROMAN AUTHORS’ WAYS OF WRITING ABOUT THE HUNS 23 2.1. Characteristics of the Huns Defined by Environment 24 2.2. Images of Nomads and Nomadic Way of Life 31 2.3. Educated Storytelling and the Accounts of the Huns 37 3. NEW NOMADIC ARRIVALS? THE FIRST DESCRIPTIONS OF THE HUNS 55 3.1. -

Model 410 Swivel Adjustable Drawbar Eye

MANUFACTURING CO. THE FIRST NAME IN QUALITY COUPLINGS Installation, Inspection, Operation & Maintenance Guide Model 410 Swivel Adjustable Drawbar Eye IMPORTANT Read these instructions completely before installing, using or attempting to repair this product. If you have any questions, call Premier at (800) 255-5387 or (503) 234-9202. Selecting The Right Equipment Whatever your application, selecting the proper equipment for the job is very important. Proper selection along with regular inspection and maintenance will help keep operating costs minimal while providing long life to each component. Below are general guidelines for selecting Premier Couplings and Drawbar Eyes. If you feel that your application is unique, please give Premier a call so that we may help you through the selection process. Follow these four steps to ensure proper selection of Premier Couplings and Drawbar Eyes. Step 1: Step 2: Step 3: Step 4: Determine “Gross Determine “Tongue Add Margin of Safety Browse Premier Trailer(s) Weight” Weight Capacity” (Dependent upon your equipment Product Catalog (GVWR(s) of towed trailers) (Maximum occurring tongue weight) and operating environment) (Based on Steps 1 - 3) Step 1: Determine “Gross Trailer(s) Weight” “Gross Trailer(s) Weight” is usually determined by the Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR). This information is attached to the trailer by the trailer manufacturer. For “Double Trailer” configurations, only the rear trailer is considered Double Trailer Configuration when selecting your Premier Coupling or Drawbar Eye. In this example, a Coupling and Drawbar Eye with a “Gross Trailer Weight” rating of 40,000 lbs. 40,000 LBS (18,143 kg) would be the minimum rating acceptable for normal, over-the- road applications (see Tongue Weight section below). -

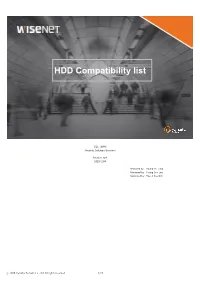

HDD Compatibility List

HDD Compatibility list SQE TEAM Security Solution Business Revision 10.3 2020.12.04 Prepared by Hyung Ho Jung Reviewed by Young Soo Lee Approved by Hyeok Rae Kim ⓒ 2019 Hanwha Techwin Co., Ltd. All rights reserved. 1/29 Contents Page Model Group List DVR, AIO, NVR, Server NVR ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 HDDs currently on the market 1. 3.5" HDD 1.1 Seagate : 2 ~ 3 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1.2 Seagate : 4 ~ 8 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.3 Western Digital : 2 ~ 3 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 1.4 Western Digital : 4 ~ 6 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 1.5 Western Digital : 8 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 1.6 Seagate & Western Digital : 1 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 2. Enterprise 3.5" HDD 2.1 Seagate : 4 ~ 8 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 2.2 Western Digital : 4 ~ 8 TB ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 2.3 Seagate/Western Digital : 4 TB (512N) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 3. 2.5" HDD 3.1 Seagate ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

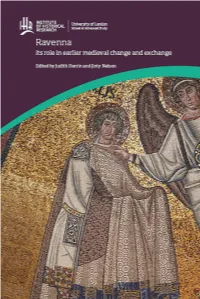

Download Free at ISBN 978‑1‑909646‑72‑8 (PDF Edition) DOI: 10.14296/917.9781909646728

Ravenna its role in earlier medieval change and exchange Ravenna its role in earlier medieval change and exchange Edited by Judith Herrin and Jinty Nelson LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2016 (ISBN 978‑1‑909646‑14‑8) This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution‑ NonCommercial‑NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY‑ NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities‑digital‑library.org ISBN 978‑1‑909646‑72‑8 (PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/917.9781909646728 iv Contents Acknowledgements vii List of contributors ix List of illustrations xiii Abbreviations xvii Introduction 1 Judith Herrin and Jinty Nelson 1. A tale of two cities: Rome and Ravenna under Gothic rule 15 Peter Heather 2. Episcopal commemoration in late fifth‑century Ravenna 39 Deborah M. Deliyannis 3. Production, promotion and reception: the visual culture of Ravenna between late antiquity and the middle ages 53 Maria Cristina Carile 4. Ravenna in the sixth century: the archaeology of change 87 Carola Jäggi 5. The circulation of marble in the Adriatic Sea at the time of Justinian 111 Yuri A. Marano 6. Social instability and economic decline of the Ostrogothic community in the aftermath of the imperial victory: the papyri evidence 133 Salvatore Cosentino 7. A striking evolution: the mint of Ravenna during the early middle ages 151 Vivien Prigent 8. Roman law in Ravenna 163 Simon Corcoran 9. -

Inventory Control Form Titanium Cannulated Humeral Nail-EX System

Inventory Control Form Titanium Cannulated Humeral Nail-EX System Patient Information: SYNTHES (USA) SYNTHES (Canada) Ltd. To Order: (800) 523-0322 To Order: (800) 668-1119 Date: Hospital: Surgeon: Procedure: Implants 7 mm Titanium Cannulated Proximal 11 mm Titanium Cannulated Humeral Humeral Nail-EX, Sterile Nail-EX, Sterile LENGTH LENGTH LENGTH 04.001.210S 150 mm 04.001.618S 190 mm 04.001.632S 260 mm 04.001.620S 200 mm 04.001.634S 270 mm 04.001.622S 210 mm 04.001.636S 280 mm 9 mm Titanium Cannulated Proximal 04.001.624S 220 mm 04.001.638S 290 mm Humeral Nail-EX, Sterile 04.001.626S 230 mm 04.001.640S 300 mm 04.001.628S 240 mm 04.001.642S 310 mm LENGTH 04.001.410S 150 mm 04.001.630S 250 mm 04.001.644S 320 mm Titanium End Cap with T25 StarDrive for 11 mm Titanium Cannulated Proximal Titanium Humeral Nail-EX Spiral Blade◊ Humeral Nail-EX, Sterile LENGTH 04.001.000 0 mm extension 04.001.610S 150 mm 04.001.001 5 mm extension 04.001.002 10 mm extension 04.001.003 15 mm extension 7 mm Titanium Cannulated Humeral Nail-EX, Sterile LENGTH LENGTH Titanium Spiral Blade for Titanium 04.001.218S 190 mm 04.001.232S 260 mm Humeral Nails◊ 04.001.220S 200 mm 04.001.234S 270 mm LENGTH LENGTH 04.001.222S 210 mm 04.001.236S 280 mm 462.634 34 mm 462.646 46 mm 04.001.224S 220 mm 04.001.238S 290 mm 462.636 36 mm 462.648 48 mm 04.001.226S 230 mm 04.001.240S 300 mm 462.638 38 mm 462.650 50 mm 04.001.228S 240 mm 04.001.242S 310 mm 462.640 40 mm 462.652 52 mm 04.001.230S 250 mm 04.001.244S 320 mm 462.642 42 mm 462.654 54 mm 462.644 44 mm 9 mm Titanium Cannulated Humeral Nail-EX, Sterile LENGTH LENGTH 04.001.418S 190 mm 04.001.432S 260 mm 04.001.420S 200 mm 04.001.434S 270 mm 04.001.422S 210 mm 04.001.436S 280 mm 04.001.424S 220 mm 04.001.438S 290 mm 04.001.426S 230 mm 04.001.440S 300 mm 04.001.428S 240 mm 04.001.442S 310 mm 04.001.430S 250 mm 04.001.444S 320 mm Synthes is a trademark of Synthes, Inc.