Augustine's War Thought - a Critical Reinterpf^Etatiqn by John Stephen Oakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.5 Mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System

4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. Technique Guide Table of Contents Introduction 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates 2 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System 4 AO Principles 5 Indications 6 Surgical Technique Preparation 7 Reduce Articular Surface 11 Insert Plate 12 Insert Screw in Central Plate Head Hole 20 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screw 20 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screw 23 Insert Screws in Surrounding Plate Head Holes 26 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 26 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 30 Insert Screws in Plate Shaft 32 Option A: 4.5 mm Cortex Screws 32 Option B: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 34 Option C: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 37 Remove Instruments 40 Product Information Implants 41 Instruments 43 Set Lists 45 Image intensifier control 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate Technique Guide Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. The Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate is part of the VA-LCP Periarticular Plating System which merges variable angle locking screw technology with conventional plating techniques. The 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System has many similarities to standard locking fixation methods, with a few important improvements. Variable angle locking screws provide the ability to create a fixed-angle construct while also allowing the surgeon the freedom to choose the screw trajectory before “fixing” the angle of the screw. -

Liberal Neutrality: a Reinterpretation and Defense*

Liberal Neutrality: A Reinterpretation and Defense* Alan Patten, Princeton University (1) Introduction After a brief ascendancy in the 1970s and `80s, the idea of liberal neutrality has fallen out of favor in recent years. A growing chorus of liberal writers has joined anti-liberal critics in arguing that there is something confused and misguided about the insistence that the state be neutral between rival conceptions of the good. Assuming we can even make sense of the idea of neutrality, these writers contend, it is a mistake to think that there is anything in liberal principles that commits the liberal state to neutrality.1 With a number of former neutralists softening their support for the idea, the rejection of neutrality is quickly becoming a consensus position, even amongst liberal political philosophers.2 According to one writer, all that remains to be done is an “autopsy” on the idea of state neutrality.3 Much of the critique of neutrality has proceeded on the basis of four assumptions. The first contrasts neutrality with perfectionism. To defend state neutrality is to deny that the state can legitimately use its power to encourage ways of life that it supposes to be valuable or to discourage ones that it regards * Earlier versions of this paper were presented at Washington University, at Queenʼs University, at the Canadian Political Science Associationʼs 2010 Annual Conference , and in a workshop at Princetonʼs University Center for Human Values. In addition to thanking the participants in and organizers of these events, I am grateful to Arash Abizadeh, Andrew Lister, Stephen Macedo, Ian MacMullen, Jonathan Quong, Ryan Pevnick, and Anna Stilz for their written feedback. -

1 Three Separation Theses James Morauta Abstract. Legal Positivism's

Three Separation Theses James Morauta Abstract . Legal positivism’s “separation thesis” is usually taken in one of two ways: as an analytic claim about the nature of law—roughly, as some version of the Social Thesis ; or as a substantive moral claim about the value of law—roughly, as some version of the No Value Thesis . In this paper I argue that we should recognize a third kind of positivist separation thesis, one which complements, but is distinct from, positivism’s analytic and moral claims. The Neutrality Thesis says that the correct analytic claim about the nature of law does not by itself entail any substantive moral claims about the value of law. I give careful formulations of these three separation theses, explain the relationships between them, and sketch the role that each plays in the positivist approach to law. [A version of this paper is published in Law and Philosophy (2004).] 1. Introduction Everybody knows that legal positivists hold that there is some kind of “separation”— some kind of distinction—between law and morality. But what exactly is this positivist separation thesis ? In what way, according to legal positivism, are law and morality distinct? There are many possible answers to this question. Legal positivism is standardly thought of as a cluster of three kinds of claims: an analytic claim about the nature of law; a moral claim about law’s value; and a linguistic claim about the meaning of the normative terms that appear in legal statements. 1 I won’t have anything to say here about the linguistic issue. -

Akrasia: Plato and the Limits of Education?

Akrasia: Plato and the Limits of Education? Colm Shanahan Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Dublin, Trinity College Supervisor: Prof. Vasilis Politis Submitted to the University of Dublin, Trinity College, August 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Signed: __________________________ Date:_____________ (Colm Shanahan) Summary In this dissertation, I shall argue for the following main claim: (1a) the motivational neutrality of reason. I will show that this concept reveals that, for Plato, (1b) reason is itself a necessary condition of the possibility of akrasia, and a central explanatory element in his account of akrasia. In presenting the soul with the capacity to take account of the whole soul, the motivational neutrality of reason seems to be the precondition of moving from having such a capacity, in a speculative manner, to generating desires and actions based upon such considerations. If this were not so, then how could the rational part of the soul, for example, put its good to one side, where such is required, to achieve the good of the whole soul? This distancing from the good associated with the rational part of the soul is precisely the grounding upon which the rational part of the soul generates the space to assess the goods of the other soul parts. -

In Defense of the Development of Augustine's Doctrine of Grace By

In Defense of the Development of Augustine’s Doctrine of Grace by Laban Omondi Agisa Submitted to the faculty of the School of Theology of the University of the South in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Sacred Theology January 2020 Sewanee, Tennessee Approved ____________________________ _______________ Adviser Date ____________________________ _______________ Second Adviser Date 2 DECLARATION I declare that this is my original work and has not been presented in any other institution for consideration of any certification. This work has been complemented by sources duly acknowledged and cited using Chicago Manual Style. Signature Date 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My study of theology was initiated in 2009 by the then Provost of St. Stephens Cathedral, Nairobi, the late Ven. Canon John Ndung’u who was a great encouragement to me. This was further made possible through my bishop the Rt. Rev. Joel Waweru and the Rev. Geoffrey Okapisi who were sources of inspiration. My studies at Carlile College (Church Army Africa) and St. Paul’s University laid a strong theological foundation and I appreciate among others the influence of the Rev. Dr. John Kiboi who introduced me to Philosophy, Systematic Theology, Ethics, and African Christian Theology that eventually became the foundation for my studies at the University of the South. I also appreciate the encouragement of my lecturers Mrs. Tabitha Waweru and Dr. Scholarstica Githinji during my Study of Education at Kenya Technical Trainers College and at Daystar University respectively. My interest in this topic came as a result of many sittings with two professors at the University of the South, Dr. -

Normative Legal Positivism, Neutrality, and the Rule of Law (Draft)

NORMATIVE LEGAL POSITIVISM, NEUTRALITY, AND THE RULE OF LAW (DRAFT) Bruno Celano Università degli studi di Palermo [email protected] www.unipa.it/celano 1ST CONFERENCE ON PHILOSOPHY AND LAW NEUTRALITY AND THEORY OF LAW Girona, 20th, 21st and 22nd of May 2010 07-celano.indd 1 5/5/10 18:26:40 07-celano.indd 2 5/5/10 18:26:40 «Neutrality is not vitiated by the fact that it is undertaken for partial [...] reasons. One does not, as it were, have to be neutral all the way down» (Waldron, 1989: 147). «Like other instruments, the law has a specific virtue which is morally neutral in being neutral as to the end to which the instru- ment is put. It is the virtue of efficiency; the virtue of the instrument as an instrument. For the law this virtue is the rule of law. Thus the rule of law is an inherent virtue of the law, but not a moral virtue as such. The special status of the rule of law does not mean that con- formity with it is of no moral importance. [...] [C]onformity to the rule of law is also a moral virtue» (Raz, 1977: 226). 1. InTRODUCTION * Usually, in jurisprudential debates what is discussed under the rubric of «neutrality» is the claim that jurisprudence is (or at least can, and should be) a conceptual, or descriptive —thus, non-normative, or mor- ally neutral (these are by no means the same thing)— inquiry: a body of theory having among its principles and its conclusions no substantive normative claims, or, specifically, no moral or ethico-political claims; and that the concept of law, as reconstructed in jurisprudential analysis * Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Seminar on legal philosophy, Uni- versity of Palermo, and at the DI.GI.TA., University of Genoa. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA Doctrina Christiana

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Medieval and Byzantine Studies School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Timothy A. Kearns Washington, D.C. 2014 Doctrina Christiana: Christian Learning in Augustine's De doctrina christiana Timothy A. Kearns, Ph.D. Director: Timothy B. Noone, Ph.D. In the twentieth century, Augustinian scholars were unable to agree on what precisely the De doctrina christiana is about as a work. This dissertation is an attempt to answer that question. I have here employed primarily close reading of the text itself but I have also made extensive efforts to detail the intellectual and social context of Augustine’s work, something that has not been done before for this book. Additionally, I have put to use the theory of textuality as developed by Jorge Gracia. My main conclusions are three: 1. Augustine intends to show how all learned disciplines are subordinated to the study of scripture and how that study of scripture is itself ordered to love. 2. But in what way is that study of scripture ordered to love? It is ordered to love because by means of such study exegetes can make progress toward wisdom for themselves and help their audiences do the same. 3. Exegetes grow in wisdom through such study because the scriptures require them to question themselves and their own values and habits and the values and habits of their culture both by means of what the scriptures directly teach and by how readers should (according to Augustine) go about reading them; a person’s questioning of him or herself is moral inquiry, and moral inquiry rightly carried out builds up love of God and neighbor in the inquirer by reforming those habits and values out of line with the teachings of Christ. -

Bertrand Russell on Sensations and Images Abdul Latif Mondal Aligarh Muslim University SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

Bertrand Russell on Sensations and Images Abdul Latif Mondal Aligarh Muslim University SUMMARY In his Theory of Mind, Russell tries to explain the mind in positive terms of sensations and images. All the mental phenomena like imagination, belief, memory, emotion, desire, will, even consciousness etc. are attempted to be established as entities, subjects, or acts by Russell. In his works The Analysis of Mind and An Outline of Philosophy, Russell offers the explanations of each mental phenomena with reference to neutrality of sensations and images, Russell does not treat them as neutral in his book The Analysis of Mind. However, in his later work, he treats them to be neutral. Russell relates especially the images to ―mnemic‖ causation. Firstly, he declares them as concerned with action in time. Subsequently, he explains them as permanent modification of the structure of the brain. He also explains sensations and images as stuff of our brain. In his book The Analysis of Mind, Russell tries to explain various mental phenomena. Firstly, he contends that all types of mental phenomena is a mix up of sensations and images and does not imply a special entity designated as ‗consciousness.‘ Secondly, Russell considers how combinations of sensations and images do, in a sense, imply consciousness in the sense of awareness. For Russell, a single sensation and image cannot in itself be deemed to be cognitive. When we try to explain a conscious mental occurrence, we do analyse it into non-cognitive constituents. We also need to show what constitutes consciousness or awareness in it. In this paper, our contention is that Russell‘s explanation of mental phenomena is especially related to these two claims. -

![Bertrand Russell's Work for Peace [To 1960]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3746/bertrand-russells-work-for-peace-to-1960-913746.webp)

Bertrand Russell's Work for Peace [To 1960]

�rticles BERTRAND RUSSELL’S WORK FOR PEACE [TO 1960] Bertrand Russell and Edith Russell Bertrand Russell may not have been aware of it, but he wrote part of the dossier that was submitted on his behalf for the Nobel Peace Prize. Before he had turned from the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament to the Committee of 100 and subsequent campaigns of the 1960s, his wife, Edith, was asked by his publisher, Sir Stanley Unwin, for an account of his work for peace. Unwin’s purpose is not known, but it is not incompatible with the next use of the document. Lady Russell responded: You have set me a task which I am especially glad to do, and I enclose a screed made up of remarks which I have extracted (the word is deliberate!) from my husband since the arrival of your letter. If there is any more information about any part of his work for peacez—zwhich has been and is, much more intensive and absorbing than this enclosure sounds as if it werez—z I should be glad to provide it if I can and if you will let me know. (7 Aug. 1960) The dictation, and her subsequent completion of the narrative (at RA1 220.024190), have not previously been published, though the “screed” was used several times. She had taken the dictation on 6 August 1960 and by next day had completed the account. Russell corrected her typescript by hand. Next we learn that Joseph Rotblat, Secretary-General of Pugwash, enclosed for her, on 2 March 1961, a copy of the “ex tracts” that were “sent to Norway” (RA1 625). -

AUGUSTINE on SUFFERING and ORDER: PUNISHMENT in CONTEXT by SAMANTHA ELIZABETH THOMPSON a Thesis Submitted in Conformity With

AUGUSTINE ON SUFFERING AND ORDER: PUNISHMENT IN CONTEXT BY SAMANTHA ELIZABETH THOMPSON A Thesis Submitted in Conformity with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Toronto © Samantha Elizabeth Thompson 2010 Augustine on Suffering and Order: Punishment in Context Samantha Elizabeth Thompson Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Augustine of Hippo argues that all suffering is the result of the punishment of sin. Misinterpretations of his meaning are common since isolated statements taken from his works do give misleading and contradictory impressions. This dissertation assembles a comprehensive account of Augustine’s understanding of the causes of suffering to show that these views are substantive and internally consistent. The argument of the dissertation proceeds by confronting and resolving the apparent problems with Augustine’s views on sin and punishment from within the broader framework of his anthropology and metaphysics. The chief difficulty is that Augustine gives two apparently irreconcilable accounts of suffering as punishment. In the first, suffering is viewed as self-inflicted because sin is inherently self-damaging. In the second, God inflicts suffering in response to sin. This dissertation argues that these views are united by Augustine’s concern with the theme of ‘order.’ The first account, it argues, is actually an expression of Augustine’s doctrine that evil is the privation of good; since good is for Augustine synonymous with order, we can then see why he views all affliction as the concrete experience of disorder brought about by sin. This context in turn allows us to see that, by invoking the ii notion of divinely inflicted punishment in both its retributive and remedial forms, Augustine wants to show that disorder itself is embraced by order, either because disorder itself must obey laws, or because what is disordered can be reordered. -

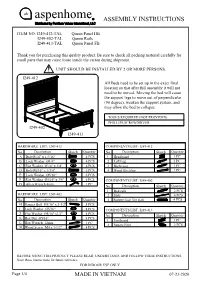

Aspenhome R ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS

ah aspenhome R ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS ITEM NO: I249-412-TAL Queen Panel HB I249-402-TAL Queen Rails I249-413-TAL Queen Panel FB Thank you for purchasing this quality product. Be sure to check all packing material carefully for small parts that may come loose inside the carton during shipment. UNIT SHOULD BE INSTALLED BY 2 OR MORE PERSONS. I249-412 All Beds need to be set up in the exact final location so that after full assembly it will not need to be moved. Moving the bed will cause the support legs to move out of perpendicular (90 degree), weaken the support system, and may allow the bed to collapse. TOOLS REQUIRED (NOT PROVIDED) PHILLIPS SCREWDRIVER I249-402 I249-413 HARDWARE LIST: I249-412 COMPONENTS LIST: I249-412 No. Description Sketch Quantity No. Description Sketch Quantity A Bolt Ø1/4" x 1-9/16" 4 PCS 1 Headboard 1 PC B Lock Washer Ø1/4" 4 PCS 2 Left Leg 1 PC C Flat Washer Ø1/4" x 3/4" 4 PCS 3 Right Leg 1 PC D Bolt Ø5/16" x 1-3/4" 6 PCS 4 Wood Stretcher 1 PC E Lock Washer Ø5/16" 6 PCS F Flat Washer Ø5/16" x 3/4" 6 PCS COMPONENTS LIST: I249-402 G Allen Wrench 4mm 1 PC No. Description Sketch Quantity 1 Bed rails 2 PCS HARDWARE LIST: I249-402 2 Slats 4 PCS No. Description Sketch Quantity 3 Support Leg (for slat) 4 PCS H Hanger Bolt Ø5/16" x 3-1/2" 8 PCS I Lock Washer Ø5/16" 8 PCS COMPONENTS LIST: I249-413 J Flat Washer Ø5/16" x1/2" 8 PCS No. -

What Is Neutral About Neutrality?

What Is Neutral about Neutrality? Bruce A. Ackerman Neutrality: a fighting word. Only neuters can be Neutral in politics. The fool who yearns for Neutrality indulges a special kind of silliness-from which lib- ertarians and communards, Maoists and Straussians are mercifully immune. There can be no politics without vision, no philosophy without commitment. Neutrality is not just another political slogan. If taken seriously, it will destroy the most distinctive feature of politics: the impossibility of reducing it to a neutral science of social engineering. Until the liberal is disabused of his absurd search for a value-free politics, his "philosophy" will remain a contemptibly superficial, if surprisingly seductive, exercise in suppression. This theme emerges only more emphatically for the different variations which are played out in the preceding pages. Despite their differences from one another, each symposiast raises questions Neutrality cannot answer-lest anyone mistake my piece of science fiction for the liberal's long-sought heavenly city. In response to my effort to reinvigorate Neutrality, my commentators reassure themselves that the liberal's image of a value-free politics remains a mirage. This is, of course, the way of all good conversations -for every Yes, a doubting But; for every No, a hopeful Maybe. But there is a special reason to welcome the conversational turn here. In raising a well-worn banner, I did not wish to make the same old liberal mistakes. A value-free politics seems no less absurd to me than to my most critical critic. Rather than somehow depoliticizing politics, Neutrality permits liberals to gain a deeper philosophical perspective on their own more obvious commitments and anxieties.