Do Cavers Need a Code of Conduct? Val Hildreth-Werker and Jim C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caving: Safety Activity Checkpoints

Caving: Safety Activity Checkpoints Caving—also called “spelunking” (speh-LUNK-ing) is an exciting, hands-on way to learn about speleology (spee-lee-AH- luh-gee), the study of caves, in addition to paleontology (pay-lee-en-TAH-luh-gee), the study of life from past geologic periods by examining plant and animal fossils. As a sport, caving is similar to rock climbing, and often involves using ropes to crawl and climb through cavern nooks and crannies. These checkpoints do not apply to groups taking trips to tourist or commercial caves, which often include safety features such as paths, electric lights, and stairways. Girl Scout Daisies and Brownies do not participate in caving. Know where to go caving. Connect with your Girl Scout council for site suggestions. Also, the National Speleological Society provides an online search tool for U.S. caving clubs, and the National Park Service provides information about National Park caves. Include girls with disabilities. Communicate with girls with disabilities and/or their caregivers to assess any needs and accommodations. Learn more about the resources and information that the National Center on Accessibility and the National Center of Physical Activities and Disabilities provide to people with disabilities. Caving Gear Basic Gear Sturdy boots with ankle protection (hiking boots for dry areas; rubber boots or wellies for wet caves) Warm, rubber gloves (to keep hands warm and protect against cuts and abrasions) Nonperishable, high-energy foods such as fruits and nuts Water Specialized Gear -

NSS Conservation and Preservation Policies ( .Pdf )

Part 2-Conservation, Management, Ethics: NSS Conservation and Preservation Policies 253 Section C-Improving Caver Ethics NSS Conservation and Preservation Policies NSS Cave Conservation Policy The National Speleological Society believes: Caves have unique scientific, recreational, and scenic values. These values are endangered by both carelessness and intentional vandalism. These values, once gone, cannot be recovered. The responsibility for protecting caves must be assumed by those who study and enjoy them. Accordingly, the intention of the Society is to work for the preservation of caves with a realistic policy supported by effective programs for: Encouraging self-discipline among cavers. Education and research concerning the causes and prevention of cave damage. Special projects, including cooperation with other groups similarly dedicated to the conservation of natural areas. Specifically: All contents of a cave-formations, life, and loose deposits-are significant for their enjoyment and interpretation. Caving parties should leave a cave as they find it. Cavers should provide means for the removal of waste. Cavers should limit marking to a few, small, removable signs as needed for surveys. Cavers should especially exercise extreme care not to accidentally break or soil formations, disturb life forms, or unnecessarily increase the number of disfiguring paths through an area. Scientific collection is professional, selective, al)d minimal. The collecting of mineral or biological material for display purposes-including previ- ously broken or dead specimens-is never justified, as it encourages others to collect and destroy the interest of the cave. The Society encourages projects such as: Establishing cave preserves. Placing entrance gates where appropriate. Opposing the sale of speleothems. -

Living with Karst Booklet and Poster

Publishing Partners AGI gratefully acknowledges the following organizations’ support for the Living with Karst booklet and poster. To order, contact AGI at www.agiweb.org or (703) 379-2480. National Speleological Society (with support from the National Speleological Foundation and the Richmond Area Speleological Society) American Cave Conservation Association (with support from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation and a Section 319(h) Nonpoint Source Grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Kentucky Division of Water) Illinois Basin Consortium (Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky State Geological Surveys) National Park Service U.S. Bureau of Land Management USDA Forest Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Geological Survey AGI Environmental Awareness Series, 4 A Fragile Foundation George Veni Harvey DuChene With a Foreword by Nicholas C. Crawford Philip E. LaMoreaux Christopher G. Groves George N. Huppert Ernst H. Kastning Rick Olson Betty J. Wheeler American Geological Institute in cooperation with National Speleological Society and American Cave Conservation Association, Illinois Basin Consortium National Park Service, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, USDA Forest Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey ABOUT THE AUTHORS George Veni is a hydrogeologist and the owner of George Veni and Associates in San Antonio, TX. He has studied karst internationally for 25 years, serves as an adjunct professor at The University of Ernst H. Kastning is a professor of geology at Texas and Western Kentucky University, and chairs Radford University in Radford, VA. As a hydrogeolo- the Texas Speleological Survey and the National gist and geomorphologist, he has been actively Speleological Society’s Section of Cave Geology studying karst processes and cavern development for and Geography over 30 years in geographically diverse settings with an emphasis on structural control of groundwater Harvey R. -

TITLE PAGE.Wpd

Proceedings of BAT GATE DESIGN: A TECHNICAL INTERACTIVE FORUM Held at Red Lion Hotel Austin, Texas March 4-6, 2002 BAT CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL Edited by: Kimery C. Vories Dianne Throgmorton Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum held March 4 -6, 2002 at the Red Lion Hotel, Austin, Texas Edited by: Kimery C. Vories Dianne Throgmorton Published by U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Surface Mining, Alton, Illinois and Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Surface Mining, Alton, Illinois Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois Copyright 2002 by the Office of Surface Mining. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bat Gate Design: A Technical Interactive Forum (2002: Austin, Texas) Proceedings of Bat Gate Design: Red Lion Hotel, Austin, Texas, March 4-6, 2002/ edited by Kimery C. Vories, Dianne Throgmorton; sponsored by U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Office of Surface Mining and Fish and Wildlife Service, Bat Conservation International, the National Cave and Karst Management Symposium, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, the National Speleological Society, Texas Parks and Wildlife, the Lower Colorado River Authority, the Indiana Karst Conservancy, and Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-885189-05-2 1. Bat ConservationBUnited States Congresses. 2. Bat Gate Design BUnited States Congresses. 3. Cave Management BUnited State Congresses. 4. Strip miningBEnvironmental aspectsBUnited States Congresses. -

Draft 8380, Cave and Karst Resources Handbook

BLM Manuals are available online at web.blm.gov/internal/wo-500/directives/dir-hdbk/hdbk-dir.html Suggested citation: Bureau of Land Management. 2015. Cave and Karst Resources Management. BLM Manual H-8380-1. *Denver, Colorado. ## Sheet H - 8380 CAVE AND KARST RESOURCES MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................................... iii I. Handbook Summary ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Significant Cave Identification and Designation ........................................................................................ 1 Chapter 3: Resource Planning ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 4: Integrating Surface and Subsurface Resources ........................................................................................... 1 Chapter 5: Implementation Strategies .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Purpose and Need for Cave/Karst Resources Management ..................................................................................... -

K26-04713-1995-V40-N03.Pdf

THE TEXAS CAVER TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 40, No. 3 September 1995 79 Edit oral Fees For Caves Noble Stidham The Texas Ca11er iB a quarterly pubHcalion of the Texas 80 Conservation Report Speleological ~tion (TSA), an internal organization of Cave Conservation Issues . David Jagnow the National Speleological Society (NSS). Issues are publiBhcd in March, June, September, and December. 83 Please Write Letters . ... Concerned Cavers Subscription J"1lta arc $15/ycar for four iBsucs of The Texas 86 General News Ca11er. This includes membership in the TSA. For only Tower of the Americas . Bill Steele $5.00 additional, or a total of $20.00, you can receive Pat Copeland's Monthly Mailing of Dated Material containing dates and places of current and future TSA, TSS, TCMA, 90 Gear Review ............... Joe Ivy TCS, and Grotto activities . Out of state subscribers, The Petzl Duo Headlamp libraries, and other institutions can receive The Texas Caver for the same rate ($15/year). Send all correspondence (other 91 Safety and Rescue Alex Villagomez than material for The Texas Caver) , subscriptions, and The Frog System ex::hanges to: The Texas Caver, P.O . Box 8026, Austin, . TelUlll 78713. Back iBsues are available at $3.00 per iBsue. 92 TCMA News ............. Jay Jorden Articles 11nd other M11terial for The Texas Caver should be Annual Membership Meeting sent to the Publications Chairman, Jay Jorden, 1518 Devon Circle, Dallas, Texas 75217-1205. The Texas Caver openly 92 TSS News Bill Elliott invites all cavcrs to submit articles, trip reports, photographs (35mm slides or any size black & white or color print on glossy 93 TSANews paper), cave maps, news events, cartoons, and/or any other 1995 TSA Competition . -

Underwater Speleology Journal of the Cave Diving Section of the National Speleological Society CONTENTS

Underwater Speleology Journal of the Cave Diving Section of the National Speleological Society CONTENTS Jackson Blue Springs. Photographer: Mat Bull...........................................Cover From the Chairman.....................................................................................3 Little Hole, Big Finds: Diving Tulum’s Chan Hol..........................................4 Agnes Milowka Memorial...........................................................................11 Skills, tips & Techniques............................................................................12 Wes Skiles Peacock Springs Interpretive Trail..........................................14 Cave diving Milestones.............................................................................17 Visit With A Cave: Madison Blue Springs..................................................18 Conservation Corner.................................................................................21 Australia: Down Under Diary.....................................................................22 Workshop 2011.........................................................................................29 News Reel.................................................................................................30 from the Chairman gene melton “The root of joy, as of duty, is to put all of one’s powers towards some great end.” - Oliver Wendell Holmes. Throughout all of our experiences, we sometimes find ourselves standing on a knife edge. We can fall off one side due to over -

A Guide to Responsible Caving Published by the National Speleological Society a Guide to Responsible Caving

A Guide to Responsible Caving Published by The National Speleological Society A Guide to Responsible Caving National Speleological Society 2813 Cave Avenue Huntsville, AL 35810 256-852-1300 [email protected] www.caves.org Fourth Edition, 2009 Text: Cheryl Jones Design: Mike Dale/Switchback Design Printing: Raines This publication was made possible through a generous donation by Inner Mountain Outfitters. Copies of this Guide may be obtained through the National Speleological Society Web site. www.caves.org © Copyright 2009, National Speleological Society FOREWORD We explore caves for many reasons, but mainly for sport or scientific study. The sport caver has been known as a spelunker, but most cave explorers prefer to be called cavers. Speleology is the scientific study of the cave environment. One who studies caves and their environments is referred to as a speleologist. This publication deals primarily with caves and the sport of caving. Cave exploring is becoming increasingly popular in all areas of the world. The increase in visits into the underground world is having a detrimental effect on caves and relations with cave owners. There are many proper and safe caving methods. Included here is only an introduction to caves and caving, but one that will help you become a safe and responsible caver. Our common interests in caving, cave preservation and cave conservation are the primary reasons for the National Speleological Society. Whether you are a beginner or an experienced caver, we hope the guidelines in this booklet will be a useful tool for remembering the basics which are so essential to help preserve the cave environment, to strengthen cave owner relations with the caving community, and to make your visit to caves a safe and enjoyable one. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

Site Management Plan, Medford District BLM

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Background ............................................................................................................................... 3 II. Life History .............................................................................................................................. 4 Habitat Associations ................................................................................................................... 4 Roosting Ecology ........................................................................................................................ 4 Foraging Behavior, Habitat, and Diet ......................................................................................... 6 Reproduction and Development ................................................................................................. 6 Behavioral ecology ..................................................................................................................... 7 III. Threats..................................................................................................................................... 7 IV. General Management Direction for Townsend’s Big-eared Bat Roost Sites ........................ 8 V. Grants Pass Resource Area Sites .......................................................................................... 10 Oak Mine .................................................................................................................................. 10 Gopher / Baby / Lamb Mine .................................................................................................... -

Caves in New Mexico and the Southwest Issue 34

Lite fall 2013 Caves in New Mexico and the Southwest issue 34 The Doll’s Theater—Big Room route, Carlsbad Cavern. Photo by Peter Jones, courtesy of Carlsbad Caverns National Park. In This Issue... Caves in New Mexico and the Southwest Cave Dwellers • Mapping Caves Earth Briefs: Suddenly Sinkholes • Crossword Puzzle New Mexico’s Most Wanted Minerals—Hydromagnesite New Mexico’s Enchanting Geology Classroom Activity: Sinkhole in a Cup Through the Hand Lens • Short Items of Interest NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO TECH http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publications/periodicals/litegeology/current.html CAVES IN NEW MEXICO AND THE SOUTHWEST Lewis Land Cave Development flowing downward from the surface. Epigenic A cave is a naturally-formed underground cavity, usually caves can be very long. with a connection to the surface that humans can enter. The longest cave in the Caves, like sinkholes, are karst features. Karst is a type of world is the Mammoth landform that results when circulating groundwater causes Cave system in western voids to form due to dissolution of soluble bedrock. Karst Kentucky, with a surveyed terrain is characterized by sinkholes, caves, disappearing length of more than 400 streams, large springs, and underground drainage. miles (643 km). The largest and most common caves form by dissolution of In recent years, limestone or dolomite, and are referred to as solution caves. scientists have begun to Limestone and dolomite rock are composed of the minerals recognize that many caves calcite (CaCO ) and dolomite (CaMg(CO ) ), which are 3 3 2 are hypogenic in origin, soluble in weak acids such as carbonic acid (H CO ), and are 2 3 meaning that they were thus vulnerable to dissolution by groundwater. -

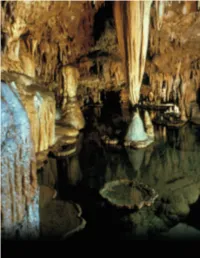

Karst Hydrology 121 Section A-Identifying and Protecting Cave Resources

Part 2-Conservation, Management, Ethics: Veni-Karst Hydrology 121 Section A-Identifying and Protecting Cave Resources Karst Hydrology: Protecting and Restoring Caves and Their Hydrologic Systems GeorgeVeni Cavers tend to be conscientious. We try to tread softly through passages to limit our impact. We clean up and restore caves that have been impacted by others. We fight to preserve and protect caves and their contents from outside impacts like urbanization. We work to improve our restoration and protection methods, and, through vehicles like this book, share that information as much as possible. Many of the adverse Many orthe adverse impacts a cave may suffer and the means to prevent impacts a cave may or alleviate them are determined by the cave's hydrology. This chapter suffer and the means provides hydrologic information and guidelines to assist cavers in protect- ing and restoring caves. It teaches the basics of how caves forn1 and how to prevent or water moves through caves and their surrounding landscapes. The chapter alleviate them are also examines common hydrologic problems and impacts on caves, and determined by the what problems can be solved by individual and group actions. cave's hydrology. The following sections are meant to reach cavers of all experience levels. References are cited for those wanting details. Specific recommendations are included, but the focus is on general principles to help guide cavers through situations that cannot be covered within this chapter. The Basics of Karst Hydrology How Water Enters, Moves Through, and Exits Caves The movement of water through caves is closely tied to the question of how caves form.