Final Report Master Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iv Supplementary Investigation on Environmental and Social Consideration

Project for Reviewing GDC’s Geothermal Development Strategy in Kenya Final Report IV SUPPLEMENTARY INVESTIGATION ON ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATION The JICA team performed an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), having the same level of Initial Environmental Examination (IEE), based on existing information, data and site surveys. This EIA included literature review on environmental and social consideration, and site survey and interview of local communities regarding the direct use of geothermal resources. Existing document review was performed during Phase I and site survey and other activities were performed during Phase II and later. The objective of this investigation was collecting and summarizing basic information in order to develop a detailed investigation plan for environmental and social consideration which will be needed during the implementation period of the GDC master plan as a loan assistance project. IV-1 Literature Review on Environmental and Social Assessment IV-1.1 National policies and laws related to environmental and social assessment EIA related Kenyan policy and domestic plan The key legal instruments which provide the framework for environmental protection and management in Kenya include: i. Constitution of Kenya ii. Kenya Vision 2030, Session Paper No. 6 of 1999 on Environment and Development iii. Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) of 1999; Amended in 2015 Relevant laws and agencies on environmental and social assessment The EMCA is the law for environmental conservation and regulation in Kenya. It stipulates the environmental impact assessment (EIA) procedure and implementation in the country. EMCA’s main objective is to provide a legal framework that would incorporate environmental considerations in the pursuit of economic and social development. -

Investigation of Silali Basin As an Extra-Terrestrial Impact Crater (ETIC) Using Remote Sensing

Journal of Environment and Earth Science www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online) Vol.6, No.2, 2016 Investigation of Silali Basin as an Extra-Terrestrial Impact Crater (ETIC) Using Remote Sensing Kipkiror Loice Jepkemboi 1*, Prof. Ucakuwun Elijah 2 & Prof. Fatuma Daudi 2 1 School of Arts and Social Science, University of Kabianga, P.O. Box 2030-20200, Kericho, Kenya 2 School of Environmental Studies, University of Eldoret, P.O. Box 1125-30100, Eldoret, Kenya Our gratitude goes to the University of Kabianga for partially funding this research study, besides keeping a track of it Abstract For years, extra-terrestrial impact cratering was esoteric. However, impacts have become very important, mainly because they have been identified as the likely immediate cause of dinosaur extinction. Impact cratering by extra-terrestrial bodies including asteroids comets and meteorites is an important geologic process, not only for the minerals that it forms, but also because of the knowledge that it is dangerous to mankind and life on earth. There is also the fact that extra-terrestrial impact crater building is a continuous process that may be going on even this very minute, somewhere in the universe. Consequently, the earth, just like other members of the solar system is targeted by extra-terrestrial falling objects. The purpose of this study was to assess the effects of impact cratering on Kenya’s environment, with focus on Silali basin. Silali basin is a depression that is found to the north of Lake Baringo; around Kapedo town. It is suspected to be an Extra –Terrestrial Impact Crater (ETIC). -

March 2016 – the Senate

MARCH 2016 KEWOPA MEMBERS HANSARD [SENATE] CHAIRS Date: 9th March 2016 Member of Parliament: Sen. Elizabeth Ongoro (Temporary Chairperson) Contribution She Made On: Chaired a Session Date: 15th March 2016 Member of Parliament: Sen. Elizabeth Ongoro (Temporary Chairperson) Contribution She Made On: Chaired a Session Date: 16th March 2016 Member of Parliament: Sen. Elizabeth Ongoro (Temporary Chairperson) Contribution She Made On: Chaired a Session Date: 16th March 2016 Member of Parliament: Sen. Elizabeth Ongoro (Temporary Chairperson) Contribution She Made On: Chaired a Session COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE Date: 1st March 2016 Member of Parliament: Sen. Elizabeth Ongoro Contribution She Made On: The County Industrial Development Bill (Senate Bill No.7 of 2014) ‘Mr. Deputy Speaker, Sir, I beg to report that the Committee of the Whole has considered The County Industrial Development Bill (Senate Bill No.7 of 2014) and seeks leave to sit again tomorrow.’ BILLS Date: 2nd March 2016 Member of Parliament: Sen. Joy Gwendo Contribution She Made On: County Library Services Bill (Senate Bill No.6 of 2015) KENYA WOMEN PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION [KEWOPA]| HANSARD [SENATE] MARCH 2016 1 ‘Mr. Temporary Speaker, Sir, I beg to move:- THAT, the County Library Services Bill (Senate Bill No. 6 of 2015) be read a Second Time. This is a simple Bill. Therefore, I will not take a long time on it as it seeks to devolve library services to the counties. It also seeks management of libraries set up in the counties. Currently, the public library services are regulated by the Kenya National Library Services (KNLS) Act which establishes a board within its main function to promote and manage the libraries. -

Subsurface Structures and Characterization of the Silali Geothermal System, Kenya Rift

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY MSc IN GEOLOGY nS SUBSURFACE STRUCTURES AND CHARACTERIZATION OF THE SILALI GEOTHERMAL SYSTEM, KENYA RIFT. / r By Kangogo Deflorah Jerobon Reg No: 156/77008/09 University of NAIROBI Library 0439129 8 A dissertation submitted to the University of Nairobi in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Geology (Applied Geophysics). 2011 f DECLARATION I certify that although I may have conferred with others in preparing for this assignment, and drawn upon a range of sources cited in this work, the content of this thesis report is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university or any other award. Signature _________ Date: Deflorah Kangogo 1 confirm that the candidate under our supervision has undertaken the work in this dissertation report. Prof. Justus Barongo Department of Geology, University of Nairobi. ABSTRACT Electrical resistivity methods are widely applied in geothermal exploration and are the cheapest means of acquiring subsurface data. Further detailed surveys like exploratory drilling which is cost intensive in an area under study is always based on accurate surface exploration results. Several exploration methods are applicable in geophysical prospecting of geothermal resources; however, this study focuses mainly on application of electromagnetic methods namely Transient Electromagnetic (TEM) and Magnetotelluric (MT). During the detailed exploration surveys of Silali geothermal prospect situated in the floor of the Northern Kenya rift, MT and TEM methods were applied. The survey was to map out the subsurface resistivity, which is then interpreted so as to provide information such as fluid filled fractures, the reservoir and the heat source. -

The East Pokot Pastoralists in Conflict Siege: Reflections on Cultural Interpretations of Persistent Conflict

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 1 No. 10 October 2013 The East Pokot Pastoralists in conflict siege: Reflections on cultural interpretations of persistent conflict Dr. Beneah Manyuru Mutsotso * * Department of Sociology and Social Work, University of Nairobi. P.O B.o.x 30197 00100 Nairobi. Kenya Email address [email protected]/ [email protected] Tel contact: +254 722833012 Abstract The East Pokot pastoralists are part of the Nilotic group that belong to the Karamoja cluster. They are found in Baringo County of North Western Kenya. They neighbor the Turkana, Samburu, Il Chamus (Njemps), Tugen and Marakwet. They always have had an acrimonious relationship with the Kenya government from the colonial period to the present.All through they have a conflictuous relationship with all the neighbouring pastoralist and agro pastoral communities over livestock and lately territory. This paper suggests that the intensity, scale and frequency of conflict has continued unabated in the face of government and other actors interventions through a combination of threat of force and/ or negotiated settlement. This paper, based on primary and secondary data, argues that the motivators of conflict from the perspective of the East Pokot are historically and culturally defined. While there exist specific cultural interpretations in relation to each community the overall cultural interpretations for conflict are presented as: revival of the sharpening stone, misbehavior and carelessness by the middle age group which has angered Tororot (God). 1.1 Background 1.2 Introduction Ever since the path breaking study by Fukui and Turton (1979) titled Warfare among East African herders, the question of conflict among pastoralists has remained high on the agenda and perspectives to understand the motivations remained elusive. -

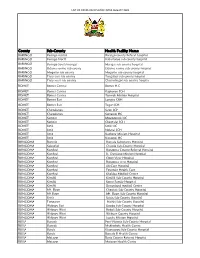

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

NATIONAL WILDLIFE CENSUS 2021 REPORT.Pdf

Written and Edited By (Authors): Brig. (Rtd) John Waweru2, Dr. Patrick Omondi1, Dr. Shadrack Ngene1, Dr. Joseph Mukeka1, Edwin Wanyonyi2, Bernard Ngoru1, Stephen Mwiu1, Daniel Muteti1, Fredrick Lala1, Linus Kariuki1, Dr. Festus Ihwagi3, Sospeter Kiambi1, Cedric Khyale1, Geoffrey Bundotich1, Dr. Fred Omengo1, Peter Hongo1, Peter Maina1, Faith Muchiri1, Dr. Mohammed Omar1, Judith Nyunja1, Joseph Edebe1, James Mathenge1, George Anyona1, Chrispin Ngesa1, John Gathua4, Lucy Njino4, Gakami Njenga4, Anthony Wandera5, Samuel Mutisya6, Redempta Njeri7, David Kimanzi8, Titus Imboma9, Jane Wambugu1, Timoth Mwinami9, Ali Kaka10 and Dr. Erustus Kanga10 1Wildlife Research and Training Institute, P.O. Box 842-20117, Naivasha, Kenya 2Kenya Wildlife Service, P.O. Box 409241-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 3Save the elephants, P.O. Box 54667-00200, Nairobi, Kenya 4Directorate of Resource Surveys and Remote Sensing, P.O. Box 47146-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 5Northern Rangeland Trust, Private Bag-60300, Isiolo, Kenya 6Ol Pajeta Conservancy, Private Bag-10400, Nanyuki, Kenya 7Space for Giants, P.O. Box 174-10400, Nanyuki, Kenya 8Mara Elephant Project, P.O. Box 2606-00502, Narok, Kenya 9National Museums of Kenya, P.O. Box 40658-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 10Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife, P.O. Box 30126-00100, Nairobi, Kenya Concept and Design by: Boniface Gor, www.digimatt.co.ke @digimattsol ©Photos: David Macharia/Versatile Photography | David Gotlib | KWS | Shatterstock | Freepik Published in July 2021 by the Wildlife Research and Training Institute (WRTI) and Kenya Wildlife -

Local Government Act

LAWS OF KENYA THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT CHAPTER 265 Revised Edition 2010 (1998) Published by the National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney General www.kenyalaw.org 2 CAP. 265 Local Government [Rev. 2010 CHAPTER 265 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section PART I—PRELIMINARY 1—Short title. 2—Interpretation. PART II—LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS 3 4 Repealed. 5—Powers of the Minister in regard to local authority areas. 6—Council may submit proposals for alterations. 7— Repealed. 8—Power to name townships. 9—Powers of minister with respect to counties. 10 11 Repealed. PART III—CONSTITUTION OF LOCAL AUTHORITY Municipal Councils 12—Establishment and incorporation of municipal councils. 13—Qualification of mayor and tenure of office. 14—Election of mayor. 15—Deputy mayor. 16—Filling vacancy in office of mayor and deputy mayor. 17—Functions of deputy mayor. 18—Mayor and deputy mayor to make declaration of acceptance. 19—Allowance to mayor. 20 21 22 Repealed. 23 24 25 26—Number of councillors. 27—Terms of office of councillors. Rev. 2010] Local Government CAP. 265 3 Section County and Town Councils 28—Establishment and incorporation of county councils and town councils. 29—Election of chairman of county and town councils. 30—Vice-chairman of county and town councils. 31—Terms of office of chairman and vice-chairman of county and town councils. 32—Filling vacancy in office of chairman and vice-chairman. 33—Functions of vice-chairman. 34—Allowance to chairman. 35 36 37 Repealed. 38 39—Number of councillors. 40—Term of office of councillors. -

Knchr Iccpr Report

ADDITIONAL REPORT TO THE UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PROVISIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS 4TH PERIODIC REPORT JANUARY 2021 KENYA NATIONAL COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS First Floor, CVS Plaza, Kasuku Road P.O.BOX 74359-00200 Nairobi, Kenya Website: www.knchr.org Email: [email protected] 1 Introduction The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) submits this additional report in update to the one submitted in September 2020 to the Human Rights Committee, so as to inform its review of the State’s Fourth Periodic Report under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights is established under Article 59 of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010 and operationalized under the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights Act 20111. It is the successor to the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights established in 2003 under the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights Act 20022. The Commission is constitutionally mandated as the principal organ of the State in ensuring compliance with obligations under international and regional human rights treaties and conventions. KNCHR is the national monitoring agency under Article 33 (2) of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities3 and has additional functions to oversight implementation of the Prevention of Torture Act4. The KNCHR has since 2004 enjoyed an Affiliate Status with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights5. The Commission is also a member of the Network of African National Human Rights Institutions (NANHRI), the regional umbrella body that brings together National Human Rights Institutions in Africa. -

Geology Nakuru-Thomson's Falls

Report No. 78 MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF KENYA GEOLOGY OF THE NAKURU-THOMSON'S FALLS- LAKE HANNINGTON AREA DEGREE SHEET No. 35 S.W. QUARTER AND 43 N.W. QUARTER (with coloured maps) by G. J. H. McCALL, B.Sc, A.R.C.S., Ph.D., D.I.C., F.G.S. Geologist I Thirty Shillings - 1967 JSBIC LIBRARY • KE - 1967.04 j'Wageningen lie Setherlands Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe | depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued , information available for consultation, following Fair Use ', Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the ' originators. For questions please contact soil.isric(â)wur.nl indicating the item reference number concerned. I GEOLOGY OF THE NAKURU-THOMSON'S FALLS- LAKE HANNINGTON AREA DEGREE SHEET No. 35 S.W. QUARTER AND 43 N.W. QUARTER (with coloured maps) by G. J. H. McCALL, B.Sc, A.R.C.S., Ph.D., D.I.C., F.G.S. Geologist |5*9> FOREWORD This report covers nearly 2,500 square miles of the central sector of the Great Rift Valley and its eastern shoulders, an area of great diversity of topography and rock-types in which are to be found many vital clues as to the origin and age of the rift. Dr. McCall's pains taking work in describing and unravelling all the evidence contained in this region therefore makes up a volume which is somewhat larger than the normal reports of the Geological Survey, but will nevertheless be of absorbing interest to geologists and geomorphologists. -

Block 12A Seismic

Earthview Geoconsultants Ltd. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROJECT REPORT FOR PROPOSED OIL AND GAS SEISMIC PROJECT IN BLOCK 12A: PARTS OF TURKANA EAST, EAST POKOT, MARAKWET WEST, BARINGO CENTRAL, MARIGAT, KEIYO SOUTH, BARINGO NORTH, MOGOTIO AND SAMBURU DISTRICTS BY TULLOW KENYA B.V. Prepared by EarthView GeoConsultants Limited P.O. BOX 10366-00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 254-20-2496208 Email: [email protected] SEPTEMBER 2011 Block 12A: EIA project report for TKBV Earthview Geoconsultants Ltd. PROJECT REPORT FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED OIL AND GAS SEISMIC SURVEY PROJECT IN BLOCK 12A: PARTS OF TURKANA EAST, EAST POKOT, MARAKWET WEST, BARINGO CENTRAL, MARIGAT, KEIYO SOUTH, BARINGO NORTH, MOGOTIO AND PART OF SAMBURU DISTRICTS SEPTEMBER 2011 Block 12A: EIA project report for TKBV Earthview Geoconsultants Ltd. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tullow Kenya B.V. (TKBV) holds an Exclusive Prospecting Right (EPR) over Block 12A, which covers nine districts (Turkana East, East Pokot, Marakwet West, Baringo Central, Marigat, Keiyo South, Baringo North, Mogotio and part of Samburu Districts) in northwest Kenya. The main objective of the seismic survey is to study in detail the assigned area of 15389.39km2, in accordance with the contractual obligations under the Production Sharing Agreement (PSC) signed with the Kenya Government on 17th September 2008 in order to delineate potential hydrocarbon prospects. This Environmental Impact Assessment Project Report has been prepared for TKBV, in accordance with the objectives established by the Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) of 1999, and subsequent related regulations. Seismic surveys are a primary tool utilized during the exploration of hydrocarbons in both onshore (land) and offshore (marine) areas. -

1 IJGES-A070 (1-22).Pdf

Vol. 4, No. 2, June 2018 Int. J. of Geol. & Earth Sci., 2018 Loice J Kipkiror, 2018 ISSN 2395-647X www.ijges.com Vol. 4, No. 2, June 2018 Research Paper © 2018 IJGES. All Rights Reserved FORMATION OF SILALI BASIN AS A COMPLEX EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL IMPACT CRATER (ETIC) Loice J Kipkiror (PhD)1* *Corresponding Author: Loice J Kipkiror [email protected] Received on: 10th April, 2018 Accepted on: 25th May, 2018 For a long time, Silali crater/basin has been described as a volcanic crater that formed through volcanicity. This would ordinarily entail the release of magma from inside the earth, through a volcanic pipe or vent, onto the earth’s surface. A violent volcanic eruption can blast the earth to form a crater. The eruption can also pile magma all around the blasted area, forming walls of lava (cooled magma). A recent study that was carried out in Silali basin: Identification of an Extra-Terrestrial Impact Crater (ETIC): A Case Study of Silali Crater, Kenya, by Kipkiror (2016), however, has unearthed facts that give an indication that Silali basin may actually be an Extra- terrestrial Impact Crater (ETIC); formed through an extra-terrestrial impact event. This involves the impact of an asteroid, comet or a meteor on the earth’s surface, leading to the formation of a crater or a meteorite. When a heavenly body impacts on the earth’s surface and excavates it, a crater is formed. If the heavenly body fails to completely burn up while transiting the earth’s atmosphere, it will land on the earth’s surface, form a shallow crater and rest on the crater as a meteorite.