TVA Best Practices Procedural Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asbestos Fibers and Other Elongate Mineral Particles: State of the Science and Roadmap for Research

CURRENT INTELLIGENCE BULLETIN 62 Asbestos Fibers and Other Elongate Mineral Particles: State of the Science and Roadmap for Research Revised Edition DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Cover Photograph: Transitional particle from upstate New York identified by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) as anthophyllite asbestos altering to talc. Photograph courtesy of USGS. CURRENT INTELLIGENCE BULLETIN 62 Asbestos Fibers and Other Elongate Mineral Particles: State of the Science and Roadmap for Research DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Disclaimer Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the Na- tional Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the spon- soring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites. Ordering Information To receive NIOSH documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at Telephone: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636) TTY: 1–888–232–6348 E-mail: [email protected] or visit the NIOSH Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh. For a monthly update on news at NIOSH, subscribe to NIOSH eNews by visiting www.cdc.gov/niosh/eNews. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011–159 (Revised for clarification; no changes in substance or new science presented) April 2011 Safer • Healthier • PeopleTM ii Foreword Asbestos has been a highly visible issue in public health for over three decades. -

Articles Devoted to Silicate Minerals from Fumaroles of the Tol- Bachik Volcano (Kamchatka, Russia)

Eur. J. Mineral., 32, 101–119, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-32-101-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Unusual silicate mineralization in fumarolic sublimates of the Tolbachik volcano, Kamchatka, Russia – Part 1: Neso-, cyclo-, ino- and phyllosilicates Nadezhda V. Shchipalkina1, Igor V. Pekov1, Natalia N. Koshlyakova1, Sergey N. Britvin2,3, Natalia V. Zubkova1, Dmitry A. Varlamov4, and Eugeny G. Sidorov5 1Faculty of Geology, Moscow State University, Vorobievy Gory, 119991 Moscow, Russia 2Department of Crystallography, St Petersburg State University, University Embankment 7/9, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia 3Kola Science Center of Russian Academy of Sciences, Fersman Str. 14, 184200 Apatity, Russia 4Institute of Experimental Mineralogy, Russian Academy of Sciences, Academica Osypyana ul., 4, 142432 Chernogolovka, Russia 5Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Piip Boulevard 9, 683006 Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Russia Correspondence: Nadezhda V. Shchipalkina ([email protected]) Received: 19 June 2019 – Accepted: 1 November 2019 – Published: 29 January 2020 Abstract. This is the initial paper in a pair of articles devoted to silicate minerals from fumaroles of the Tol- bachik volcano (Kamchatka, Russia). These papers contain the first systematic data on silicate mineralization of fumarolic genesis. In this article nesosilicates (forsterite, andradite and titanite), cyclosilicate (a Cu,Zn- rich analogue of roedderite), inosilicates (enstatite, clinoenstatite, diopside, aegirine, aegirine-augite, esseneite, “Cu,Mg-pyroxene”, wollastonite, potassic-fluoro-magnesio-arfvedsonite, potassic-fluoro-richterite and litidion- ite) and phyllosilicates (fluorophlogopite, yanzhuminite, “fluoreastonite” and the Sn analogue of dalyite) are characterized with a focus on chemistry, crystal-chemical features and occurrence. -

MINERALOGY for PETROLOGISTS Comprising a Guidebook and a Full Color CD-ROM, This Reference Set Offers Illustrated Essentials to Study Mineralogy, Applied to Petrology

MINERALOGY for PETROLOGISTS for MINERALOGY Comprising a guidebook and a full color CD-ROM, this reference set offers illustrated essentials to study mineralogy, applied to petrology. While there are some excellent reference works available on this subject, this work is unique for its data richness and its visual character. MINERALOGY for PETROLOGISTS With a collection of images that excels both in detail and aesthetics, 151 minerals are presented in more than 400 plates. Different facies and paragenesis, both in natural polarized light, are shown for every mineral and optical data, sketches of the crystal habitus, chemical composition, occurrence and a brief description are Optics, Chemistry and Occurrences included. The accompanying user guide gives a general introduction to microscope mineral observation, systematic mineralogy, mineral chemistry, occurrence, of Rock-Forming Minerals stability, paragenesis, structural formula calculation and its use in petrology. This compact set will serve as a field manual to students, researchers and Michel Demange professionals in geology, geological, mining, and mineral resources engineering to observe and determine minerals in their studies or field work. Dr. Michel Demange has devoted his career to regional geology and tectonics of metamorphic and magmatic terranes and to ore deposits. Graduated from the École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris and holding a Docteur-es-Sciences from the University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris VI, he has been active in a rich variety of geological projects and investigations around the world. In combination with his teaching and research activities at the École des Mines in Paris, France, he headed various research studies. This book benefits from the great experience in field M. -

A Comparative Study of Jadeite, Omphacite and Kosmochlor Jades from Myanmar, and Suggestions for a Practical Nomenclature

Feature Article A Comparative Study of Jadeite, Omphacite and Kosmochlor Jades from Myanmar, and Suggestions for a Practical Nomenclature Leander Franz, Tay Thye Sun, Henry A. Hänni, Christian de Capitani, Theerapongs Thanasuthipitak and Wilawan Atichat Jadeitite boulders from north-central Myanmar show a wide variability in texture and mineral content. This study gives an overview of the petrography of these rocks, and classiies them into ive different types: (1) jadeitites with kosmochlor and clinoamphibole, (2) jadeitites with clinoamphibole, (3) albite-bearing jadeitites, (4) almost pure jadeitites and (5) omphacitites. Their textures indicate that some of the assemblages formed syn-tectonically while those samples with decussate textures show no indication of a tectonic overprint. Backscattered electron images and electron microprobe analyses highlight the variable mineral chemistry of the samples. Their extensive chemical and textural inhomogeneity renders a classiication by common gemmological methods rather dificult. Although a deinitive classiication of such rocks is only possible using thin-section analysis, we demonstrate that a fast and non-destructive identiication as jadeite jade, kosmochlor jade or omphacite jade is possible using Raman and infrared spectroscopy, which gave results that were in accord with the microprobe analyses. Furthermore, current classiication schemes for jadeitites are reviewed. The Journal of Gemmology, 34(3), 2014, pp. 210–229, http://dx.doi.org/10.15506/JoG.2014.34.3.210 © 2014 The Gemmological Association of Great Britain Introduction simple. Jadeite jade is usually a green massive The word jade is derived from the Spanish phrase rock consisting of jadeite (NaAlSi2O6; see Ou Yang, for piedra de ijada (Foshag, 1957) or ‘loin stone’ 1999; Ou Yang and Li, 1999; Ou Yang and Qi, from its reputed use in curing ailments of the loins 2001). -

BURMESE JADE: the INSCRUTABLE GEM by Richard W

BURMESE JADE: THE INSCRUTABLE GEM By Richard W. Hughes, Olivier Galibert, George Bosshart, Fred Ward, Thet Oo, Mark Smith, Tay Thye Sun, and George E. Harlow The jadeite mines of Upper Burma (now Myanmar) occupy a privileged place in the If jade is discarded and pearls destroyed, petty thieves world of gems, as they are the principal source of top-grade material. This article, by the first will disappear, there being no valuables left to steal. foreign gemologists allowed into these impor- — From a dictionary published during the reign of tant mines in over 30 years, discusses the his- Emperor K’ang Hsi (1662–1722 AD) , as quoted by Gump, 1962 tory, location, and geology of the Myanmar jadeite deposits, and especially current mining erhaps no other gemstone has the same aura of mys- activities in the Hpakan region. Also detailed tery as Burmese jadeite. The mines’ remote jungle are the cutting, grading, and trading of location, which has been off-limits to foreigners for jadeite—in both Myanmar and China—as P well as treatments. The intent is to remove decades, is certainly a factor. Because of the monsoon rains, some of the mystery surrounding the Orient’s this area is essentially cut off from the rest of the world for most valued gem. several months of the year, and guerrilla activities have plagued the region since 1949 (Lintner, 1994). But of equal importance is that jade connoisseurship is almost strictly a Chinese phenomenon. People of the Orient have developed jade appreciation to a degree found nowhere else in the world, but this knowledge is largely locked away ABOUT THE AUTHORS in non-Roman-alphabet texts that are inaccessible to most Mr. -

Anto A, Larson C, Horton D. 2012. Libby Vermiculite Exposure And

REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Libby vermiculite exposure and risk of developing asbestos-related lung and pleural diseases Vinicius C. Antao, Theodore C. Larson, and D. Kevin Horton Purpose of review The vermiculite ore formerly mined in Libby, Montana, contains asbestiform amphibole fibers of winchite, richterite, and tremolite asbestos. Because of the public health impact of widespread occupational and nonoccupational exposure to amphiboles in Libby vermiculite, numerous related studies have been published in recent years. Here we review current research related to this issue. Recent findings Excess morbidity and mortality classically associated with asbestos exposure have been well documented among persons exposed to Libby vermiculite. Excess morbidity and mortality have likewise been documented among persons with only nonoccupational exposure. A strong exposure–response relationship exists for many malignant and nonmalignant outcomes and the most common outcome, pleural plaques, may occur at low lifetime cumulative exposures. Summary The public health situation related to Libby, Montana, has led to huge investments in public health actions and research. The resulting studies have added much to the body of knowledge concerning health effects of exposures to Libby amphibole fibers specifically and asbestos exposure in general. Keywords amphibole, asbestos, Libby, respiratory diseases, vermiculite INTRODUCTION Libby vermiculite was shipped throughout the US to A vermiculite mine and mill located near Libby, more than 200 domestic processing and receiving Montana, operated from the early 1920s until facilities [6]. Interestingly, the first identification by 1990. Vermiculite is a naturally occurring laminar public health authorities of pulmonary abnormal- aluminum-iron-magnesium silicate. It expands ities associated with Libby vermiculite concerned when heated, and has been employed in many exposures outside of Libby. -

Description and Recognition of Potassic-Richterite, an Amphibole Supergroup Mineral from the Pajsberg Ore Field, Värmland, Sweden

Mineralogy and Petrology (2019) 113:7–16 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00710-018-0623-6 ORIGINAL PAPER Description and recognition of potassic-richterite, an amphibole supergroup mineral from the Pajsberg ore field, Värmland, Sweden Dan Holtstam1 & Fernando Cámara2 & Henrik Skogby1 & Andreas Karlsson1 & Jörgen Langhof1 Received: 17 April 2018 /Accepted: 12 July 2018 /Published online: 10 August 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract A B C T W Potassic-richterite, ideally K (NaCa) Mg5 Si8O22 (OH)2, is recognized as a valid member of the amphibole supergroup (IMA- CNMNC 2017–102). Type material is from the Pajsberg Mn-Fe ore field, Filipstad, Värmland, Sweden, where the mineral occurs in a Mn-rich skarn, closely associated with mainly phlogopite, jacobsite and tephroite. The megascopic colour is straw yellow to grayish brown and the luster vitreous. The nearly anhedral crystals, up to 4 mm in length, are pale yellow (non-pleochroic) in thin section and −1 optically biaxial (−), with α = 1.615(5), β = 1.625(5), γ = 1.635(5). The calculated density is 3.07 g·cm . VHN100 is in the range 610– 946. Cleavage is perfect along {110}. EPMA analysis in combination with Mössbauer and infrared spectroscopy yields the empirical 3+ 3+ formula (K0.61Na0.30Pb0.02)∑0.93(Na1.14Ca0.79Mn0.07)∑2(Mg4.31Mn0.47Fe 0.20)∑5(Si7.95Al0.04Fe 0.01)∑8O22(OH1.82F0.18)∑2 for a frag- ment used for collection of single-crystal X-ray diffraction data. The infra-red spectra show absorption bands at 3672 cm−1 and 3736 cm−1 for the α direction. -

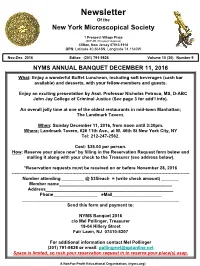

Newsletter of the New York Microscopical Society

Newsletter Of the New York Microscopical Society 1 Prospect Village Plaza (66F Mt. Prospect Avenue) Clifton, New Jersey 07013-1918 GPS: Latitude 40.8648N, Longitude 74.1540W Nov-Dec 2016 Editor: (201) 791-9826 Volume 10 (30) Number 9 NYMS ANNUAL BANQUET DECEMBER 11, 2016 What: Enjoy a wonderful Buffet Luncheon, including soft beverages (cash bar available) and desserts, with your fellow-members and guests. Enjoy an exciting presentation by Asst. Professor Nicholas Petraco, MS, D-ABC John Jay College of Criminal Justice (See page 3 for add’l info). An overall jolly time at one of the oldest restaurants in mid-town Manhattan; The Landmark Tavern. When: Sunday December 11, 2016, from noon until 3:30pm. Where: Landmark Tavern, 626 11th Ave., at W. 46th St New York City, NY Tel: 212-247-2562. Cost: $35.00 per person. How: Reserve your place now* by filling in the Reservation Request form below and mailing it along with your check to the Treasurer (see address below). *Reservation requests must be received on or before November 28, 2016 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Number attending _________ @ $35/each = (write check amount) _______ Member name______________________________________________ Address____________________________________________________ Phone__________________ eMail____________________ ________________________________________________________________ Send this form and payment to: NYMS Banquet 2016 c/o Mel Pollinger, Treasurer 18-04 Hillery Street Fair Lawn, NJ 07410-5207 For additional information contact Mel Pollinger (201) 791-9826 or email: [email protected] Space is limited, so rush your reservation request in to reserve your place(s) asap. A Not-For-Profit Educational Organization, (nyms.org) Save a Tree: Get The Extended Newsletter: By Email Only New York Microscopical Society Board of Managers (Officers Term 2016-2017) President, John Scott, [email protected]; (646)339-6566, Curator, Archivist. -

Characterization of Fibrous Mordenite: a First Step for the Evaluation of Its Potential Toxicity

crystals Article Characterization of Fibrous Mordenite: A First Step for the Evaluation of Its Potential Toxicity Dario Di Giuseppe 1,2 1 Department of Chemical and Geological Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Via G. Campi 103, I-41125 Modena, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Sciences and Methods for Engineering, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Via Amendola 2, I-42122 Reggio Emilia, Italy Received: 4 August 2020; Accepted: 28 August 2020; Published: 31 August 2020 Abstract: In nature, a huge number of unregulated minerals fibers share the same characteristics as asbestos and therefore have potential adverse health effects. However, in addition to asbestos minerals, only fluoro-edenite and erionite are currently classified as toxic/pathogenic agents by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Mordenite is one of the most abundant zeolites in nature and commonly occurs with a fibrous crystalline habit. The goal of this paper is to highlight how fibrous mordenite shares several common features with the well-known carcinogenic fibrous erionite. In particular, this study has shown that the morphology, biodurability, and surface characteristics of mordenite fibers are similar to those of erionite and asbestos. These properties make fibrous mordenite potentially toxic and exposure to its fibers can be associated with deadly diseases such as those associated with regulated mineral fibers. Since the presence of fibrous mordenite concerns widespread geological formations, this mineral fiber should be considered dangerous for health and the precautionary approach should be applied when this material is handled. Future in vitro and in vivo tests are necessary to provide further experimental confirmation of the outcome of this work. -

Meeker Et Al. 2003. the Composition of Amphiboles from the Rainy

American Mineralogist, Volume 88, pages 1955–1969, 2003 The Composition and Morphology of Amphiboles from the Rainy Creek Complex, Near Libby, Montana G.P. MEEKER,1,* A.M. BERN,1 I.K. BROWNFIELD,1 H.A. LOWERS,1,2 S.J. SUTLEY,1 T.M. HOEFEN,1 AND J.S.VANCE3 1U.S. Geological Survey, Denver Microbeam Laboratory, Denver, Colorado 80225, U.S.A. 2Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado, 80401, U.S.A. 3U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 8, Denver, Colorado 80204, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Thirty samples of amphibole-rich rock from the largest mined vermiculite deposit in the world in the Rainy Creek alkaline-ultramafic complex near Libby, Montana, were collected and analyzed. The amphibole-rich rock is the suspected cause of an abnormally high number of asbestos-related diseases reported in the residents of Libby, and in former mine and mill workers. The amphibole-rich samples were analyzed to determine composition and morphology of both fibrous and non-fibrous amphiboles. Sampling was carried out across the accessible portions of the deposit to obtain as complete a representation of the distribution of amphibole types as possible. The range of amphibole compositions, determined from electron probe microanalysis and X-ray diffraction analysis, indi- cates the presence of winchite, richterite, tremolite, and magnesioriebeckite. The amphiboles from Vermiculite Mountain show nearly complete solid solution between these end-member composi- tions. Magnesio-arfvedsonite and edenite may also be present in low abundance. An evaluation of the textural characteristics of the amphiboles shows the material to include a complete range of morphologies from prismatic crystals to asbestiform fibers. -

Geology of the Crater of Diamonds State Park and Vicinity, Pike County, Arkansas

SPS-03 STATE OF ARKANSAS ARKANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bekki White, State Geologist and Director STATE PARK SERIES 03 GEOLOGY OF THE CRATER OF DIAMONDS STATE PARK AND VICINITY, PIKE COUNTY, ARKANSAS by J. M. Howard and W. D. Hanson Little Rock, Arkansas 2008 STATE OF ARKANSAS ARKANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bekki White, State Geologist and Director STATE PARK SERIES 03 GEOLOGY OF THE CRATER OF DIAMONDS STATE PARK AND VICINITY, PIKE COUNTY, ARKANSAS by J. M. Howard and W. D. Hanson Little Rock, Arkansas 2008 STATE OF ARKANSAS Mike Beebe, Governor ARKANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bekki White, State Geologist and Director COMMISSIONERS Dr. Richard Cohoon, Chairman………………………………………....Russellville William Willis, Vice Chairman…………………………………...…….Hot Springs David J. Baumgardner………………………………………….………..Little Rock Brad DeVazier…………………………………………………………..Forrest City Keith DuPriest………………………………………………………….….Magnolia Becky Keogh……………………………………………………...……..Little Rock David Lumbert…………………………………………………...………Little Rock Little Rock, Arkansas 2008 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..................... 1 Geology…………………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Prairie Creek Diatreme Rock Types……………………………….…………...……...………… 3 Mineralogy of Diamonds…………………….……………………………………………..……. 6 Typical shapes of Arkansas diamonds…………………………………………………………… 6 Answers to Frequently Asked Questions……………..……………………………….....……… 7 Definition of Rock Types……………………………………………………………………… 7 Formation Processes.…...…………………………………………………………….....…….. 8 Search Efforts……………...……………………………...……………………...………..…. -

Richterite and Actinolite from the Siilinjärvi Carbonatite Complex, Finland

RICHTERITE AND ACTINOLITE FROM THE SIILINJÄRVI CARBONATITE COMPLEX, FINLAND KAUKO PUUSTINEN PUUSTINEN, KAUKO 1972: Richterite and actinolite from the Siilinjärvi carbon- atite complex, Finland. Bull. Geol. Soc. Finland 44, 83—86. Chemical, optical and X-ray data are given for the richterite in the glimmerite and actinolite in the syenite of the Siilinjärvi carbonatite complex. Kauko Puustinen, Technical University, Dept. of Mining and Metallurgi, 02150 Otaniemi, Finland. Introduction accessory mineral in connection with the am- phibole-rich types of glimmerite. The Siilinjärvi carbonatite complex is situated Syenite consists mainly of microcline, am- some 20 km to the north of the city of Kuopio, phibole and pyroxene. Albite, quartz and biotite Eastern Finland, at lat. 63°08' N and long. are found as accessories. 27°44' E. It forms a roughly tabular, subvertical Carbonatite proper forms mixed rocks to- body, some 16 km long and up to 1.5 km wide. gether with the glimmerite, the amount of am- A detailed description of the complex has been phibole in the carbonatite being, however, given by Puustinen (1971). neglible. The sequence of emplacement began with the intrusion of the ultramafic phase (glimmerite), followed by the intrusion of syenite. The carbon- Occurrence atite proper (sövite) was intruded into the glim- meritic rocks. Amphibole is very common in the glimmerite. Glimmerite is a quartz- and feldspar-free rock Locally its amount may be up to 50 % by volume which consists of phlogopite, alkali amphibole, but usually is less than 15 %. It represents a apatite and some calcite. It is medium grained primary crystallization and does not show any with color varying from red-brown to black.