Valuation of SAS AB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIBN Accident Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner, Oslo Airport, 18

Issued June 2020 REPORT SL 2020/14 REPORT ON THE AIR ACCIDENT AT OSLO AIRPORT GARDERMOEN, NORWAY ON 18 DECEMBER 2018 WITH BOEING 787-9 DREAMLINER, ET-AUP OPERATED BY ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES The Accident Investigation Board has compiled this report for the sole purpose of improving flight safety. The object of any investigation is to identify faults or discrepancies which may endanger flight safety, whether or not these are causal factors in the accident, and to make safety recommendations. It is not the Board's task to apportion blame or liability. Use of this report for any other purpose than for flight safety shall be avoided. Accident Investigation Board Norway • P.O. Box 213, N-2001 Lillestrøm, Norway • Phone: + 47 63 89 63 00 • Fax: + 47 63 89 63 01 www.aibn.no • [email protected] This report has been translated into English and published by the AIBN to facilitate access by international readers. As accurate as the translation might be, the original Norwegian text takes precedence as the report of reference. Photos: AIBN and Trond Isaksen/OSL The Accident Investigation Board Norway Page 2 INDEX ACCIDENT NOTIFICATION ............................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. FACTUAL INFORMATION .............................................................................................. 4 1.1 History of the flight ............................................................................................................. -

Erfiðleikar SAS Goup

Erfiðleikar SAS Höfundur: Róbert Ágústsson Leiðbeinandi: Jafet Ólafsson Háskólinn á Bifröst – Viðskiptadeild BS Ritgerð Vorið 2012 2 Staðfesting lokaverkefnis til B.S.c gráðu í Viðskiptafræði Heiti á Lokaverkefni: Erfiðleikar SAS Farið er yfir sögu og ákvarðanatökur þessa þekkta og rótgróna flugfélags í Skandinavíu ásamt því að skoða helstu áhrifaþætti um stjórnun flugfélags. Höfundur: Róbert Ágústsson Kt: 120275-4109 Hefur verið metið samkvæmt reglum og kröfum Háskólans á Bifröst og hlotið Lokaeinkunnina:_________ 3 Erfiðleikar SAS Höfundur: Róbert Ágústsson Leiðbeinandi: Jafet Ólafsson Háskólinn á Bifröst – Viðskiptadeild BS Ritgerð Vorið 2012 4 Útdráttur Flugfélagið SAS er eitt af rótgrónu flugfélögunum í heiminum. Það hefur verið við lýði fremur lengi og því upplifað þá þróun sem orðið hefur í fluggeiranum síðustu ár. Í ritgerðinni verður skoðað hvernig flugfélaginu hefur gengið í þeim öldusjó sem flugheimurinn er og ástæðna fyrir slæmu gengi leitað. Það verður gert t.d. með því að fara yfir sögu og stöðu SAS, sögu flugsins í Evrópu og helstu ákvarðanir stjórnenda fyrirtækisins. Aðferðafræðinni sem verður beitt er upplýsingaöflun þar sem safnað er saman gögnum úr ýmsum áttum, t.d. ársskýrslur, blaðagreinar, heimasíður flugfélaga sem og aðrar heimasíður o.fl. til þess að afla gagna og talna um viðkomandi efni. Einnig voru notaðar eigindlegar aðferðir við gagnaöflun eins og viðtöl úr blaðagreinum, til að fá sem nákvæmasta mynd af veruleikanum í flugheiminum. Ekki verður leitast við að kafa ofan í eitthvað eitt atriði, heldur reynt að skoða yfirborðið, heildina og söguna til þess að fá sem mesta yfirsýn yfir hvernig SAS hefur verið rekið síðustu ár, sem og hvernig það er rekið í dag. -

B2065df2c95f7d42.Pdf

1 Disclaimer The information contained in this fact book is intended to be a general summary of the listed parent company SAS AB (Reg no 556606-8499) and its subsidiaries, hereinafter referred to as ‘SAS’ or the ‘SAS Group’ and its activities as at 31 October 2017 or otherwise the date specified in the relevant information and does not purport to be complete in any respect. The information in this document is not advice about investing in shares in SAS (or any other financial instrument or product), nor is it intended to influence, or be relied upon by any person in making an investment decision in relation to SAS shares (or any other financial instrument or product). The information in this fact book does not consider the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. Accordingly, you should consider your own objectives, financial situation and needs when considering the information in this document and seek independent investment, legal, tax, accounting or such other advice as you consider appropriate before making any financial or investment decision. No responsibility is accepted by SAS or any of its directors, officers, employees, agents or affiliates, nor any other person, for any of the information contained in this document or for any action taken by you based on the information or opinions expressed in this document. The information in this document contains historic information about the performance of SAS and shares in SAS. That information is historic only, and is not an indication or representation about the future performance of SAS or shares in SAS (or any other financial instrument or product). -

Denmark State Aid SA.58342 (2020/N) – Sweden COVID-19: Recapitalisation of SAS AB

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 17.8.2020 C(2020) 5750 final In the published version of this decision, PUBLIC VERSION some information has been omitted, pursuant to articles 30 and 31 of Council This document is made available for Regulation (EU) 2015/1589 of 13 July 2015 information purposes only. laying down detailed rules for the application of Article 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, concerning non-disclosure of information covered by professional secrecy. The omissions are shown thus […] Subject: State Aid SA.57543 (2020/N) – Denmark State Aid SA.58342 (2020/N) – Sweden COVID-19: Recapitalisation of SAS AB Excellences, 1. PROCEDURE (1) Following pre-notification contacts,1 by electronic notifications of 11 August 2020, the Kingdom of Denmark (“Denmark”) and the Kingdom of Sweden (“Sweden”) notified to the Commission their participation in the recapitalisation (the “Measure”) of SAS AB (“SAS”). SAS is the parent company of SAS 1 Denmark and Sweden submitted a draft notification form on 12 June 2020. Following informal exchanges with the Commission, Denmark and Sweden submitted additional information on 16 June 2020. The Commission sent Denmark and Sweden requests for information on 16, 19, 23 and 30 June 2020, to which Denmark and Sweden replied on 18, 22, 23 June 2020 and 2 July 2020. The Commission sent further requests for information on 2, 6 and 10 July 2020 to which Denmark and Sweden replied on 3, 8, 13 and 23 July 2020. Further information was submitted by Denmark and Sweden on 24, 27, 30 and 31 July 2020 and 1 and 2 August 2020. -

Will SAS Continue to Fly? - a Valuation of a Company in Crisis

Will SAS continue to fly? - A valuation of a company in crisis - Will SAS continue to fly? - A valuation of a company in crisis - Supervisor: Jens Borges Authors: Maren Emilie Birkeland Christian Emanuel Friedrich Christ Study Line: Applied Economics and Finance STU: 118 pages 1 Hand in Date: 29/10/2009 Will SAS continue to fly? - A valuation of a company in crisis - Executive Summary The main objective of this thesis is to analyse the strategy of the SAS Group and its current competitive environment in order to value the share price of the SAS Group as of the 30th of June 2009, and discuss whether the group is able to overcome its current crisis. To evaluate this, an analysis of the company’s macro- and microenvironment has been undertaken and its internal strategy has been analysed. Additionally financial statements have been forecasted and a share value has been estimated via the use of DCF, economic profit, multiple and liquidation analysis. Scandinavian Airline System Group (SAS Group) is Scandinavia’s leading Airline; it operates various hub’s in the region and has a market share of around 50%. The company is currently in a crisis due to high competition coupled with falling demand. The SAS Group is mainly affected by economical factors, high competition as well as deregulation. Preferences of passenger have changed from being service orientated to being more price conscious. Consequently it has been recognised, that the airline industry is a highly competitive industry with extremely tight profit margins. Additionally, the airline is performing poorly compared to its competitors in key areas, but has some unrealised competitive advantages. -

I. FACTS 1. Procedure

Case No: 73991 Event No: 703841 Dec. No: 273/14/COL EFTA SURVEILLANCE AUTHORITY DECISION of 9 July 2014 on the financing of Scandinavian Airlines through the new Revolving Credit Facility (NORWAY) The EFTA Surveillance Authority (“the Authority”), HAVING REGARD to the Agreement on the European Economic Area (“the EEA Agreement”), in particular to Articles 61, 109, and Protocols 26 and 27, HAVING REGARD to the Agreement between the EFTA States on the Establishment of a Surveillance Authority and a Court of Justice (“the Surveillance and Court Agreement”), in particular to Article 24, HAVING REGARD to Protocol 3 to the Surveillance and Court Agreement (“Protocol 3”), in particular to Article 1(2) of Part I and Article 7(2) of Part II, WHEREAS: I. FACTS 1. Procedure (1) In late October 2012, the Authority and the European Commission (“the Commission”) were informally contacted by Norway, Denmark and Sweden (jointly “the States”) in relation to their intention to participate in a new Revolving Credit Facility (“the new RCF”) in favour of Scandinavian Airlines (“SAS” or “the SAS Group” or “the company”). On 12 November 2012, the States decided to participate in the new RCF without however formally notifying the measure to the Authority. (2) On 5 February 2013, the Authority received a complaint from the European Low Fares Airline Association (“ELFAA”) against the participation of the States in the RCF. With a letter dated 18 February 2013, the Authority invited the Norwegian authorities to submit their comments on the complaint and on the allegations of unlawful state aid. (3) The Norwegian authorities replied with a letter dated 25 March 2013. -

Uncle Sam's Ground Handling Year

WINTER 2015/SPRING 2016 AIRLINE GROUND AGS SERVICES www.ags-airlinegroundservices.com WESTJET HANDLING WHAT IF WORLDWIDE DIRECTORY ACROSS LESSONS FROM UK SAYS OF GROUND THE WAVES THE CLASSROOM ADIOS TO EU? SERVICE PROVIDERS From XS to XXL. Fraport provides the perfect service tailored to every plane. Every airline customer is unique – and should expect customized service. A ground handling partner with years of experience and expertise, Fraport AG knows exactly what each airline needs. Together, we develop the right solutions designed to meet your specific requirements. Flexibility is a major advantage, especially when we have to get late arriving planes out even faster. We know the processes on the ground and can move into action with speed, precision and efficiency. We put performance first, not size. Let us be your flexible ground handling partner. Contact the Fraport ground services: phone +49 (0) 69 690-71101 / [email protected] / www.fraport.com Fraport. The Airport Managers. EDITOR’S LETTER | WINTER 2015/SUMMER 2016 WINTER 2015/SPRING 2016 AIRLINE GROUND LETTER FROM AGS SERVICES THE EDITOR www.ags-airlinegroundservices.com WESTJET HANDLING WHAT IF WORLDWIDE DIRECTORY ACROSS LESSONS FROM UK SAYS OF GROUND THE WAVES THE CLASSROOM ADIOS TO EU? SERVICE PROVIDERS here is an old adage in journalism: follow the money. Ground handlers, like the rest of aviation, are reaping PARVEEN RAJA Publisher the benefits of lower prices at the pump that the world [email protected] has enjoyed this year. Our look at the American ground handling market discovers that the lower prices are Tallowing airlines to slash fares – thus attracting more passengers that HARLEY KHAN Head of Commercial have to be handled. -

The Norwegian Air Transport Market in the Future

RAPPORT 1205 Svein Bråthen, Nigel Halpern and George Williams THE NORWEGIAN AIR TRANSPORT MARKET IN THE FUTURE Some possible trends and scenarios Svein Bråthen, Nigel Halpern and George Williams The Norwegian Air Transport Market in the Future Some possible trends and scenarios Rapport 1205 ISSN: 0806‐0789 ISBN: 978‐82‐7830‐169‐2 Møreforsking Molde AS 11. april 2012 Tittel The Norwegian Air Transport Market in the Future Forfatter(e) Svein Bråthen, Nigel Halpern and George Williams Rapport nr 1205 Prosjektnr. 2379 Prosjektnavn: Luftfartsmarkedet Prosjektleder Svein Bråthen Finansieringskilde Samferdselsdepartementet Rapporten kan bestilles fra: Høgskolen i Molde, biblioteket, Boks 2110, 6402 MOLDE: Tlf.: 71 21 41 61, Faks: 71 21 41 60, epost: [email protected] – www.himolde.no Sider: 82 Pris: Kr 100,‐ ISSN 0806‐0789 ISBN 978‐82‐7830‐169‐2 Short Summary The purpose of this report has been to address the Norwegian air transport market today and in which direction it is likely to develop in the future. The main objective is to address the following questions: Is the long run sustainability of today’s well‐functioning network dependent on that existing airlines maintain their position in the Norwegian market? How can other airlines be expected to enter the Norwegian market if one or more of the incumbents reduces their level of service, be it from financial or other reasons? Will the structure of airlines or airline ownership have an influence on the level of service that is offered to the market? How will policy framework conditions and the current economic situation (influencing e.g. air transport demand and the level of competition in the airline industry) affect the supply of air transport services? The findings indicate that there are challenges in Norwegian air transport, connected to the weak financial state of affairs for SAS, Norwegian’s expansion plans with a unit fleet of larger aircraft and a network of 800 metre local airports with a limited number of competitors for the PSO routes and scarce aircraft availability. -

Scandinavian Airlines and Datalex Partner on Multi-Year Digital Retailing Transformation Programme

Scandinavian Airlines and Datalex Partner on Multi-Year Digital Retailing Transformation Programme Dublin, Ireland, 25 October 2018: Datalex plc (ISE: DLE), a leading provider of digital commerce solutions to global travel retailers, is pleased to announce a new long-term agreement with Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) to support the SAS digital transformation strategy with New Distribution Capability (NDC), merchandising and order management of all products and services across sales channels. The platform will support the dynamic shopping, pricing and promotion of offers based on data collection and intelligence to deliver a personalised retail experience to around 30 million SAS customers. Kati Andersson, VP Digital Sales & Distribution at SAS said: "We are pleased to announce the selection of Datalex as the SAS partner of choice in our journey towards NDC capability. Our objective is to deploy a full NDC platform certified to the latest IATA standards. This will allow us to make the right offer to the right customer at the right time, via the right channel, on the right platform. Of course, all handling of customer data will be in compliance with GDPR.” “We have the ambition to deliver a digital customer experience second to none, and the Datalex commercial platform is a great complement to our existing digital capabilities and supports our business and IT strategy very well”, added Mats O. Eklund, VP Commercial IT & Digital Development at SAS. Datalex CEO Aidan Brogan said: “We are delighted to partner with SAS on this exciting project. As a proven digital commerce platform for high volume travel retailers, we look forward to bringing a full cloud-hosted NDC platform to production with SAS, enabling its digital retail strategy to provide consistent, competitive and optimised offers across all sales channels.” About SAS SAS is Scandinavia’s leading airline and has an attractive offering to frequent travelers. -

Group Annual Report 2010

/ Preface / Highlights 2010 / Financial highlights / Management's financial review / Traffic / Commercial / International / / Review of other financial items / Risk factors / Outlook 2011 / Shareholder information / / Reference to Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance / Board of Directors / Executive Management / Financial Statements Group Annual Report 2010 / Preface / Highlights 2010 / Financial highlights / Management's financial review / Traffic / Commercial / International / / Preface / Highlights 2010 / Financial highlights / Management's financial review / Traffic / Commercial / International / / Review of other financial items / Risk factors / Outlook 2011 / Shareholder information / / Review of other financial items / Risk factors / Outlook 2011 / Shareholder information / / Reference to Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance / Board of Directors / Executive Management / Financial Statements / Reference to Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance / Board of Directors / Executive Management / Financial Statements Contents Management’s report Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Highlights 2010 ������������������������������������������������������������������5 Financial highlights ������������������������������������������������������������� 6 Management’s financial review �������������������������������������������8 Traffic ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 Commercial ����������������������������������������������������������������������16 -

SAS 2004 Q2 Report

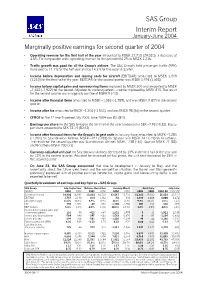

SAS Group Interim Report January-June 2004 Marginally positive earnings for second quarter of 2004 • Operating revenue for the first half of the year amounted to MSEK 27,710 (29,010), a decrease of 4.5%. For comparable units, operating revenue for the period fell 4.2% or MSEK 1,216. • Traffic growth was good for all the Group's airlines. The SAS Group's total passenger traffic (RPK) increased by 11.1% for the half year and by 14.3% for the second quarter. • Income before depreciation and leasing costs for aircraft (EBITDAR) amounted to MSEK 1,449 (1,210) for the first half of the year. EBITDAR for the second quarter was MSEK 1,493 (1,608). • Income before capital gains and nonrecurring items improved by MSEK 300 and amounted to MSEK –1,622 (-1,922) for the period. Adjusted for currency effects, income improved by MSEK 415. The result for the second quarter was marginally positive at MSEK 9 (-13). • Income after financial items amounted to MSEK –1,583 (-1,789), and was MSEK 0 (87) in the second quarter. • Income after tax amounted to MSEK –1,304 (-1,533), and was MSEK 98 (66) in the second quarter. • CFROI for the 12-month period July 2003-June 2004 was 8% (8%). • Earnings per share for the SAS Group in the first half of the year amounted to SEK –7.93 (-9.32). Equity per share amounted to SEK 72.14 (80.42). • Income after financial items for the Group’s largest units in January-June amounted to MSEK –1,283 (-1,281) for Scandinavian Airlines, MSEK –221 (-283) for Spanair and MSEK 241 (-19) for Braathens. -

SAS Delivers Substantial Earnings Improvement

SAS Year-end Report November 2014 – October 2015 SAS Year-end Report November 2014 – October 2015 SAS delivers substantial earnings improvement August 2015 – October 2015 November 2014 – October 2015 • Income before tax: MSEK 867 (-450) • Income before tax: MSEK 1,417 (-918) • Income before tax and nonrecurring items: MSEK 1,338 (789) • Income before tax and nonrecurring items: MSEK 1,174 (-697) • Revenue: MSEK 10,903 (10,966) • Revenue: MSEK 39,650 (38,006) • Unit revenue (PASK) declined 0.5%1 • Unit revenue (PASK) increased 3.8%1 • Unit cost (CASK) increased 3.5%2 • Unit cost (CASK) increased 3.3%2 • EBIT margin: 11.8% (-2.3%) • EBIT margin: 5.6% (0.4%) • Net income for the period: MSEK 517 (-303) • Net income for the period: MSEK 956 (-719) • Earnings per common share: SEK 1.31 (-1.21) • Earnings per common share: SEK 1.84 (-3.03) • The outlook for the full year 2015/2016 is presented on page 8 • The Board of Directors proposes that no dividends be paid to holders of SAS AB’s common shares • The Board proposes a dividend of SEK 50 on each preference share 1) Currency adjusted. 2) Currency adjusted and excluding jet fuel. Comments by the President and CEO of SAS: “SAS reported positive income before tax and nonrecurring items Altogether, the product enhancements and the implemented cost of MSEK 1,174 for the 2014/2015 fiscal year. This was a significant measures have created new preconditions enabling us to open new year-on-year improvement, primarily driven by our commercial long-haul routes to Los Angeles, Miami and Boston next year.