Cinema of WERNER HERZOG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Nightmare, Or the Revelation of the Uncanny in Three

The American Nightmare, or the Revelation of the Uncanny in three documentary films by Werner Herzog La pesadilla americana, o la revelación de lo extraño en tres documentales de DIEGO ZAVALA SCHERER1 Werner Herzog http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7362-4709 This paper analyzes three Werner Herzog’s films: How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1976), Huie’s Sermon (1981) and God´s Angry Man (1981) through his use of the sequence shot as a documentary device. Despite the strong relation of this way of shooting with direct cinema, Herzog deconstructs its use to generate moments of filmic revelation, away from a mere recording of events. KEYWORDS:Documentary device, sequence shot, Werner Herzog, direct cinema, ecstasy. El presente artículo analiza tres obras de la filmografía de Werner Herzog: How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1976), Huie´s Sermon (1981) y God´s Angry Man (1981), a partir del uso del plano secuencia como dispositivo documental. A pesar del vínculo de esta forma de puesta en cámara con el cine directo, Herzog deconstruye su uso para la generación de momentos de revelación fílmica, lejos del simple registro. PALABRAS CLAVE: Dispositivo documental, plano secuencia, Werner Herzog, cine directo, éxtasis. 1 Tecnológico de Monterrey, México. E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 01/09/17. Accepted: 14/11/17. Published: 12/11/18. Comunicación y Sociedad, 32, may-august, 2018, pp. 63-83. 63 64 Diego Zavala Scherer INTRODUCTION Werner Herzog’s creative universe, which includes films, operas, poetry books, journals; is labyrinthine, self-referential, iterative … it is, we might say– in the words of Deleuze and Guattari (1990) when referring to Kafka’s work – a lair. -

“Of the Creatures Who Are Doomed to Perish, to Fall”: Mythology and Time

“Of the Creatures who are doomed to perish, to fall”: Mythology and Time in Herzog’s Apocalyptic, Science Fiction Films Tyson Namow This essay analyses German filmmaker Werner Herzog’s (b. 1942- ) films Fata Morgana (1970), Lessons of Darkness (Lektionen in Finsternis ) (1992) and The Wild Blue Yonder (2005). Each of these films shares formal char- acteristics, such as being divided by chapter inter-titles and using voice over narration. However, they also have different iconographic features. Fata Morgana is set in the natural, desert landscapes of Africa. It shows quiet, other-worldly beauty among the ruins of civilisation. The landscapes in this film contain disintegrating relics of human culture, such as wrecked automobiles, aeroplanes and other machine parts. It is not until the twenty- minute mark of the film that the first human figure is seen. They are sub- limely dwarfed on the horizon line of an immense desert terrain. Lessons of Darkness is set in Kuwait at the end of the first Gulf War during the period when the last of the burning oil wells were being extinguished. The film presents Kuwait as an unnamed planet that exists somewhere in our solar system. On the one hand, the audience knows that this planet is Earth and that it has been devastated by human action. On the other hand, the film also presents it as a mutilated planet on fire that reflects Herzog’s private, apocalyptic imagination. The Wild Blue Yonder is largely comprised of dif- ferent found-footage. This includes images shot under an ice sheet in Ant- arctica by Henry Kaiser and images shot in 1991 by astronauts from inside COLLOQUY text theory critique 21 (2011). -

Inicio Dissertacao

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Gabriel Kitofi Tonelo WERNER HERZOG, DOCUMENTARISTA: FIGURAS DA VOZ E DO CORPO CAMPINAS 2012 i ii UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ARTES Gabriel Kitofi Tonelo WERNER HERZOG, DOCUMENTARISTA: FIGURAS DA VOZ E DO CORPO Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual de Campinas para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Multimeios. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fernão Vitor Pessoa de Almeida Ramos CAMPINAS, 2012 iii iv v vi Resumo Este trabalho pretende analisar a obra de documentários do cineasta alemão Werner Herzog sob a ótica da autorreflexão do diretor, através de sua voz e de seu corpo, em seus documentários e da relação estabelecida entre Herzog e a narrativa em cada filme. Procura- se estabelecer como a característica nasceu em sua filmografia e como evoluiu ao longo das cinco décadas de sua atividade como cineasta. Relacionam-se os processos da inserção de Werner Herzog em seus filmes com a teoria, própria do campo do Cinema Documentário, referente à inserção do sujeito-da-câmera na narrativa fílmica. Tomando como ponto de partida as reflexões surgidas no final da década de 1950 acerca da participação do cineasta na narrativa (Cinema Vérité) até as teorias de uma narrativa documentária profundamente voltada para o universo do próprio cineasta, popularizadas nos anos 1980, pode-se dizer que a autorreflexão do cineasta na narrativa é uma questão viva no campo teórico do Cinema Documentário e que é constantemente problematizada e renovada na produção documentária contemporânea. Palavras-Chave: Werner Herzog, Cinema Documentário, Subjetividade, Autoria. vii viii Abstract This work intends to analyse german filmmaker's Werner Herzog documentary ouevre, under the optics of the director's voice and body self-reflexion in his documentaries and the relationship between Herzog and his narratives in each work. -

Wetenschappelijke Verhandeling

UNIVERSITEIT GENT FACULTEIT POLITIEKE EN SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN WERNER HERZOG EN THE ECSTATIC TRUTH: OP ZOEK NAAR DE GRENS TUSSEN FICTIE EN DOCUMENTAIRE Wetenschappelijke verhandeling aantal woorden: 21405 BART WILLEMS MASTERPROEF COMMUNICATIEWETENSCHAPPEN afstudeerrichting FILM- EN TELEVISIESTUDIES PROMOTOR: PROF. DR. DANIEL BILTEREYST COMMISSARIS: PHILIPPE VAN MEERBEECK COMMISSARIS: GERTJAN WILLEMS ACADEMIEJAAR 2011 - 2012 ABSTRACT Werner Herzog, algemeen beschouwd als deel uitmakend van de Neue Deutsche Film beweging, kende het laatste decennium een revival en een hernieuwde waardering van zijn werk. In deze thesis wordt onderzocht hoe Herzogs concept van 'the ecstatic truth' in vele gevallen in strijd is met de genreregels van de documentaire, en zich tegelijk bevindt op de dunne grens tussen fictie en documentaire. Na een korte uiteenzetting van Herzogs leven en werk ga ik dieper in op zijn basisconcept van 'the ecstatic truth'. Vervolgens is er een bespreking van een tiental van Herzogs vroege documentaires, waarin wordt op zoek gegaan naar 'the ecstatic truth'. Na een schetsing van enkele analysemodellen wordt aangetoond dat dit concept gevormd wordt op alle niveaus van analyse, wat duidt op de elasticiteit ervan. Uiteindelijk wordt een van Herzogs meest recente films, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, geanalyseerd op alle niveaus van de modellen, op zoek naar het concept van 'the ecstatic truth'. Dit concept blijkt nog steeds nadrukkelijk aanwezig te zijn in Herzogs manier van realiteitsvorming, zij het in een iets minder flagrante vorm dan ooit het geval was. Herzogs zoektocht is er een naar een perspectief buiten onze werkelijkheid, die weliswaar na al die jaren nog steeds de grenzen van het genre aftast, maar deze grenzen tegelijk overstijgt. -

Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo Free

FREE CONQUEST OF THE USELESS: REFLECTIONS FROM THE MAKING OF FITZCARRALDO PDF Werner Herzog | 320 pages | 01 Jul 2010 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780061575549 | English | New York, United States Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo by Werner Herzog It reveals him to be witty, compassionate, microscopically observant and -- your call -- either maniacally determined or admirably persevering. Around this vision Herzog fashioned a script about an aspiring rubber baron who yearns to bring opera to the Amazon, a dream requiring him to haul a steamship over a mountain from one river to another to gain access to the rubber. They form black lines on the cornices of buildings. The entire square is filled with their excited fluttering and twittering. Arriving from all different directions, the swarms of birds meet in the air above the Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo, circling like tornados in dizzying spirals. Then, as if a whirlwind were sweeping through, they suddenly descend onto the square, darkening the sky. The young ladies put up umbrellas to shield themselves from droppings. It lies there all spongy, belly-up, and is so disgusting that none of us has had the nerve to get rid of it. The effect is spellbinding. Mauch said he could not take any more, he was going to faint, and I told him to go ahead. Herzog replaced Robards with Kinski, his lead from three previous films, who presented a new set of problems. Laurent bush outfit. He comes across as impatient and wants to do everything himself, right now. -

Information & Bibliothek

DVD / Blu-Ray-Gesamtkatalog der Bibliothek / Catálogo Completo de DVDs e Blu-Rays da Biblioteca Abkürzungen / Abreviações: B = Buch / Roteiro; D = Darsteller / Atores; R = Regie / Diretor; UT = Untertitel / Legendas; dtsch. = deutsch / alemão; engl. = englisch / inglês; port. = portugiesisch / português; franz. = französisch / francês; russ. = russisch / russo; span. = spanisch / espanhol; chin. = chinesisch / chinês; jap. = japanisch / japonês; mehrsprach. = mehrsprachig / plurilingüe; M = Musiker / M úsico; Dir. = Dirigent / Regente; Inter. = Interprete / Intérprete; EST = Einheitssachtitel / Título Original; Zwischent. = Zwischentitel / Entretítulos ● = Audio + Untertitel deutsch / áudio e legendas em alemão Periodika / Periódicos ------------------------------- 05 Kub KuBus. - Bonn: Inter Nationes ● 68. Film 1: Eine Frage des Vertrauens - Die Auflösung des Deutschen Bundestags. Film 2: Stelen im Herzen Berlins - Das Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas. - 2005. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus , 68) ● 69: Film 1: Im Vorwärtsgang - Frauenfußball in Deutschland. Film 2: Faktor X - Die Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft und die digitale Zukunft. - 2005.- DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus ; 69) ● 70. Film 1: Wie deutsch darf man singen? Film 2: Traumberuf Dirigentin. - 2006. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus ; 70) ● 71. Film 1: Der Maler Jörg Immendorff. Film 2: Der junge deutsche Jazz. - 2006. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus ; 71) ● 72. Film 1: Die Kunst des Bierbrauens. Film 2: Fortschritt unter der Karosserie. - 2006. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. -

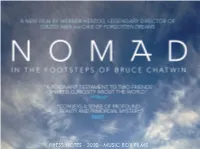

Bruce Chatwin, a Kindred Spirit Who Dedicated His Life to Illuminating the Mysteries of the World

PRESS NOTES - 2020 - MUSIC BOX FILMS LOGLINE Werner Herzog travels the globe to reveal a deeply personal portrait of his friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit who dedicated his life to illuminating the mysteries of the world. SYNOPSIS Werner Herzog turns the camera on himself and his decades-long friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit whose quest for ecstatic truth carried him to all corners of the globe. Herzog’s deeply personal portrait of Chatwin, illustrated with archival discoveries, film clips, and a mound of “brontosaurus skin,” encompasses their shared interest in aboriginal cultures, ancient rituals, and the mysteries stitching together life on earth. WERNER HERZOG Werner Herzog was born in Munich on September 5, 1942. He grew up in a remote mountain village in Bavaria and studied History and German Literature in Munich and Pittsburgh. He made his first film in 1961 at the age of 19. Since then he has produced, written, and directed more than sixty feature- and documentary films, such as Aguirre der Zorn Gottes (AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD, 1972), Nosferatu Phantom der Nacht (NOSFERATU, 1978), FITZCARRALDO (1982), Lektionen in Finsternis (LESSONS OF DARKNESS, 1992), LITTLE DIETER NEEDS TO FLY (1997), Mein liebster Feind (MY BEST FIEND, 1999), INVINCIBLE (2000), GRIZZLY MAN (2005), ENCOUNTERS AT THE END OF THE WORLD (2007), Die Höhle der vergessenen Träume (CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS, 2010). Werner Herzog has published more than a dozen books of prose, and directed as many operas. Werner Herzog lives in Munich and Los Angeles. -

Werner Herzog, Le Geste En Suspens

Werner Herzog, le geste en suspens Barbara RYCKEWAERT Werner Herzog, le geste en suspens ECOLE NATIONALE SUPÉRIEURE DES ARTS DÉCORATIFS 2009 remerciements à Clarisse Hahn SOMMAIRE Avant-Propos ............................................................ 11 Introduction ............................................................ 13 Définitions ................................................................ 21 La représentation du suspens .................................... 23 I. LES HÉROS HERZOGIENS 1. Altitude et conquête de l’inutile ............................ 35 Le «Grand» et le «Petit» (Deleuze) ........................... 47 2. Visions, rêves et états seconds ................................ 55 Perception .................................................................. 66 L’Énigme de Kaspar Hauser ......................................... 70 3. Un certain rapport au chamanisme Le mythe du vol ......................................................... 81 Chamanes, forgerons et alchimistes ........................... 83 Rituels, musique et danse............................................ 87 Bestiaire ..................................................................... 100 4. Paysages ................................................................... 112 II. INDIVIDU, LANGAGE, DISPARITION 1. Individu et société Le guide et l’exclu ........................................................ 123 Démarche et place du réalisateur, Expérience .............. 125 2. Werner Herzog et le langage Utilisation de la voix off / texte ................................... -

Complete Works Films

Complete works Films 2020 Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds 2019 Family Romance, LLC 2019 NOMAD – In the footsteps of Bruce Chatwin 2018 Meeting Gorbachev (co-director André Singer) 2017 Into the Inferno 2016 Salt and Fire 2016 Lo and Behold 2014 Queen of the Desert 2013 From One Second to the Next 2012/13 On Death Row I + II WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 2011 Into the Abyss - A Tale of Death, a Tale of Life 2010 Ode auf den Morgen der Menschheit (Ode to the Dawn of Man) 2010 Die Höhle der vergessenen Träume (Cave of Forgotten Dreams) 2009 La Bohéme 2009 My Son My Son What Have Ye Done 2008 Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans 2007 Encounters at the End of The World 2006 Rescue Dawn 2005 The Wild Blue Yonder 2005 Grizzly Man 2004 The White Diamond 2003 Rad der Zeit (Wheel of Time) WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 2002 Christ and Demons in New Spain 2001 Ten Thousand Years Older 2001 Pilgrimage 2000 Invincible 1999 Gott und die Beladenen (The Lord and the Laden) 1999 Mein liebster Feind (My Best Fiend) 1999 Schwingen der Hoffnung aka Julianes Sturz in den Dschungel (Wings of Hope) 1997 Little Dieter Needs to Fly 1995 Tod für fünf Stimmen (Death for Five Voices) 1994 Die Verwandlung der Welt in Musik (The Transformation of the World into Music) 1993 Glocken aus der Tiefe (Bells from the Deep) 1992 Lektionen in Finsternis (Lessons of Darkness) 1991 Film Lektionen (Film Lesson) WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria -

Motifs of Fiction in Werner Herzog's Films Chantal Poch [email protected], Pompeu Fabra University

Inner and deeper: Motifs of fiction in Werner Herzog's films Chantal Poch [email protected], Pompeu Fabra University Volume 7.2 (2019) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI /cinej.2019.224 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The emphasis on the mix of facts and inventions has prevailed in the studies about Bavarian director Werner Herzog’s treatment of fiction, leading to the same result again and again: for Herzog, poetic truth is more important than factual truth. But how can we go beyond this conclusion? This paper will try to open an alternative path of analysis more adequate to his philosophy of filmmaking, one that works through the detection of visual and narrative motifs in his films, thus searching the impact of Herzog’s idea of fiction into his poetics. Keywords: Werner Herzog; German Cinema; Motifs; Fiction; Ecstatic Truth New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Inner and deeper: Motifs of fiction in Werner Herzog's films Chantal Poch Introduction Asking ourselves about the nature of fiction in film brings up to the question whether this fiction acts as an opposite of truth or, indeed, as truth itself. Bavarian director Werner Herzog has built an entire oeuvre regarding this problem: from the blurry lines between his fictional movies and documentaries to the recurrent inclusion of false quotes and events on his scripts, all of his films seem to add something to the same direction: the confusion of fact and fiction. -

The Shadows of Dreams Cinema’S Layers of Medialization

The Shadows of Dreams Cinema’s Layers of Medialization by Jan-Helge Weidemann A thesis submied in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literature Approved Dissertation Commiee Prof. Dr. em. K. Ludwig Pfeier, chair Jacobs University Bremen Prof. Dr. Immacolata Amodeo Jacobs University Bremen Prof. Dr. Leonardo Boccia Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil Date of Defense: June 7, 2012 School of Humanities & Social Sciences Statutory Declaration Family Name, Given/First Name: Weidemann, Jan-Helge Matriculation Number: 842485 Kind of Thesis Submitted: PhD Thesis English: Declaration of Authorship I hereby declare that the thesis submitted was created and written solely by myself without any external support. Any sources, direct or indirect, are marked as such. I am aware of the fact that the contents of the thesis in digital form may be revised with regard to usage of unauthorized aid as well as whether the whole or parts of it may be identied as plagiarism. I do agree my work to be entered into a database for it to be compared with existing sources, where it will remain in order to enable further comparisons with future theses. This does not grant any rights of reproduction and usage, however. The Thesis has been written independently and has not been submitted at any other university for the conferral of a PhD degree; neither has the thesis been previously published in full. German: Erklärung der Autorenschaft (Urheberschaft) Ich erkläre hiermit, dass die vorliegende Arbeit ohne fremde Hilfe ausschließlich von mir erstellt und geschrieben worden ist. Jedwede verwendeten Quellen, direkter oder indirekter Art, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht worden. -

Complete Works Books

Complete works Books 2004 EROBERUNG DES NUTZLOSEN, München, Hanser. Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo, by Werner Herzog, hardcover, 306 pages, Ecco Books/Harper Collins Press. 1987 COBRA VERDE, Filmerzählung, München, Hanser. Also translated into Croatian, French, and Italian. 1984 WO DIE GRÜNEN AMEISEN TRÄUMEN: Filmerzählung, München, Hanser. Also translated into French and Italian. 1982 NOSFERATU, IL PRINCIPE DELLA NOTTE, Due racconti cinematografici, Milano, Ulbulibri. 1982 FITZCARRALDO, NOSFERATU, STROSZEK, Paris, Mazarine. 1982 FITZCARRALDO FILMBUCH, München, Schirmer/Mosel. Also translated into Italian, Polish, and Dutch. WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 1982 FITZCARRALDO: ERZÄHLUNG, München, Hanser. Also translated into Dutch, English, Italian, Russian. 1980 SCREENPLAYS: AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD, EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF AND GOD AGAINST ALL AND LAND OF SILENCE AND DARKNESS, trans. by Alan Greenberg and Martje Herzog, New York, Tanam. 1979 DREHBÜCHER III: STROSZEK, NOSFERATU: Zwei Filmerzählungen, München, Hanser. Also translated into Italian. 1978 10 POEMS, Zehn Gedichte, Akzente Nr. 3, Munich 1978 1978 OF WALKING IN ICE, Vom Gehen im Eis, C. Hanser Verlag Munich 1978, Rauriser Prize of Literature 1979 1977 DREHBÜCHER II: AGUIRRE, DER ZORN GOTTES: JEDER FÜR SICH UND GOTT GEGEN ALLE; LAND DES SCHWEIGENS UND DER DUNKELHEIT, München, Skellig. Also translated into English. 1977 DREHBÜCHER I: LEBENSZEICHEN, AUCH ZWERGE HABEN KLEIN ANGEFANGEN: FATA MORGANA, München, Skellig. 1976 L'ÉNIGME DE KASPAR HAUSER (JEDER FÜR SICH UND GOTT GEGEN ALLE), in AVANT-SCÈNE CINÉMA, 176 (November). Also translated into Italian. WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 1976 HEART OF GLASS, by Alan Greenberg, with text by Werner Herzog and Herbert Achternbusch, Munich, Skellig.