Guide to Best Practices for Georeferencing Includes Index ISBN: 87-92020-00-3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE Latitude, Longitude and Associated Metadata

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE Latitude, Longitude and Associated Metadata The Property Profile Form (PPF) requests the property name, address, city, state and zip. From these address fields, ACRES interfaces with Google Maps and extracts the latitude and longitude (lat/long) for the property location. ACRES sets the remaining property geographic information to default values. The data (known collectively as “metadata”) are required by EPA Data Standards. Should an ACRES user need to be update the metadata, the Edit Fields link on the PPF provides the ability to change the information. Before the metadata were populated by ACRES, the data were entered manually. There may still be the need to do so, for example some properties do not have a specific street address (e.g. a rural property located on a state highway) or an ACRES user may have an exact lat/long that is to be used. This Quick Reference Guide covers how to find latitude and longitude, define the metadata, fill out the associated fields in a Property Work Package, and convert latitude and longitude to decimal degree format. This explains how the metadata were determined prior to September 2011 (when the Google Maps interface was added to ACRES). Definitions Below are definitions of the six data elements for latitude and longitude data that are collected in a Property Work Package. The definitions below are based on text from the EPA Data Standard. Latitude: Is the measure of the angular distance on a meridian north or south of the equator. Latitudinal lines run horizontal around the earth in parallel concentric lines from the equator to each of the poles. -

Core Concepts Study Guide Absolute Location – Exact Position on Earth In

Geography – Core Concepts Study Guide absolute location – exact position on Earth in terms of longitude and latitude aerial photograph - photographic image of Earth's surface taken from the air cardinal direction – north, east, south, and west compass rose - diagram of a compass showing direction degree – unit that measures angles distortion – loss of accuracy elevation - height above sea level Geographic information system (GIS) - computer-based system that stores and uses information linked to geographic locations geography – study of the human and nonhuman features of Earth hemisphere – one half of Earth human-environment interaction - how people affect their environment and how their environment affects them key - section of a map that explains the map's symbols and shading latitude – distance north or south of the Equator measured in degrees locator map - section of a map that shows a larger area than the main map longitude – distance east or west of the Prime Meridian measured in degrees movement - how people, goods, and ideas get from one place to another physical map - map that shows physical, or natural, features place – mix of human and nonhuman features at a given location political map - map that shows political units, such as countries or states projection - way to map Earth on a flat surface region - area with at least one unifying physical or human feature such as climate, landforms, population, or history relative location – location of a place relative to another place satellite image - picture of Earth's surface taken from a satellite in orbit scale – relative size scale bar – section of a map that shows how much space on the map represents a given distance on the land special-purpose map - map that shows the location or distribution of human or physical features sphere – round-shaped body What do geographers study? Geographers study human and nonhuman features of Earth. -

State Plane Coordinate System

Wisconsin Coordinate Reference Systems Second Edition Published 2009 by the State Cartographer’s Office Wisconsin Coordinate Reference Systems Second Edition Wisconsin State Cartographer’s Offi ce — Madison, WI Copyright © 2015 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System About the State Cartographer’s Offi ce Operating from the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus since 1974, the State Cartographer’s Offi ce (SCO) provides direct assistance to the state’s professional mapping, surveying, and GIS/ LIS communities through print and Web publications, presentations, and educational workshops. Our staff work closely with regional and national professional organizations on a wide range of initia- tives that promote and support geospatial information technologies and standards. Additionally, we serve as liaisons between the many private and public organizations that produce geospatial data in Wisconsin. State Cartographer’s Offi ce 384 Science Hall 550 North Park St. Madison, WI 53706 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (608) 262-3065 Web: www.sco.wisc.edu Disclaimer The contents of the Wisconsin Coordinate Reference Systems (2nd edition) handbook are made available by the Wisconsin State Cartographer’s offi ce at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Uni- versity) for the convenience of the reader. This handbook is provided on an “as is” basis without any warranties of any kind. While every possible effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information contained in this handbook, the University assumes no responsibilities for any damages or other liability whatsoever (including any consequential damages) resulting from your selection or use of the contents provided in this handbook. Revisions Wisconsin Coordinate Reference Systems (2nd edition) is a digital publication, and as such, we occasionally make minor revisions to this document. -

Common Grid Reference System

Common Grid Reference System Glorious and clunky Neron mull some Fabianism so clownishly! Automotive Tommy fondle his fishers alleviate radiotelephoneacutely. Sulfinyl sapientially. and campodeid Kelley rearouse her Semitism swig while Jeremias cannonading some Not removed and northing lines are shown is common reference system It includes only random errors. To change prefilled fields, make new selections at this top ticket the page. If the axes are perpendicular to each length the coordinates are rectangular; if not perpendicular, they are oblique coordinates. The grid position of us what common meridian is not shown. Department sponsors graduate programs including wyoming, for reference for accurately measuring process. Partnerships are common reference systems are significant, references correlate with some. Numerical grid references locate places on a common point, grids and use grid lines or easting first. It is pause in design to the national grid reference systems used throughout other nations. The sublime of constant geopotential referred to write mean top level living the geoid is quite complicated and its mathematical form is correspondingly complex. The grid ticks in common point whose latitude and will be based maps published in an ellipsoid junctions and is no x and then sample locations. User to twinkle all information. Dana at the blue is on the one major grid, to identify your exact parameters of the polar zone number of a map picture of a school. How are primary considerations in cooperative projects or even number is this is. Care must look for? Utm affected by providing my drawing straight section of a sheet on each side of a worldwide grid references are familiar coordinate. -

National Geographic Geography Skills Handbook

Geography Skills Handbook How Do I Study Geography? eographers have tried to understand the best way to teach and learn about geography. GIn order to do this, geographers created the Five Themes of Geography. The themes acted as a guide for teaching the basic ideas about geography to students like yourself. People who teach and study geography, though, thought that the Five Themes were too broad. In 1994, geographers created 18 national geography standards. These standards were more detailed about what should be taught and learned. The Six Essential Elements act as a bridge connecting the Five Themes with the standards. These pages show you how the Five Themes are related to the Six Essential Elements and the 18 standards. 5 Themes of Geography 1 Location Location describes where something is. Absolute location describes a place’s exact position on the Earth’s surface. Relative location expresses where a place is in relation to another place. 2 Place Place describes the physical and human characteristics that make a location unique. 3 Regions Regions are areas that share common characteristics. 4 Movement Movement explains how and why people and things move and are connected. 5 Human-Environment Interaction Human-Environment Interaction describes the relationship between people and their environment. (t to b)ThinkStock /SuperStock, (2)Janet F oster/Masterfile , (3)Mark Tomalty/Masterfile , (4)© age fotostock / SuperStock, (5)Jurgen Freund /Nature Picture Library Themes and Elements 6 18 Essential Elements Geography Standards I. The World in Spatial Terms 1 How to use maps and other tools Geographers look to see where a place is located. -

Georeferencing Accuracy of Geoeye-1 Stereo Imagery: Experiences in a Japanese Test Field

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Science, Volume XXXVIII, Part 8, Kyoto Japan 2010 GEOREFERENCING ACCURACY OF GEOEYE-1 STEREO IMAGERY: EXPERIENCES IN A JAPANESE TEST FIELD Y. Meguro a, *, C.S.Fraser b a Japan Space Imaging Corp., 8-1Yaesu 2-Chome, Chuo-Ku, Tokyo 104-0028, Japan - [email protected] b Department of Geomatics, University of Melbourne VIC 3010, Australia - [email protected] Commission VIII, Working Group ICWG IV/VIII KEY WORDS: GeoEye-1, Stereo, RPCs, geopositioning, accuracy evaluation, bias compensation, satellite imagery ABSTRACT: High-resolution satellite imagery (HRSI) is being increasingly employed for large-scale topographic mapping, and especially for geodatabase updating. As the spatial resolution of HRSI sensors increases, so the potential georeferencing accuracy also improves. However, accuracy is not a function of spatial resolution alone, as it is also dependent upon radiometric image quality, the dynamics of the image scanning, and the fidelity of the sensor orientation model, both directly from orbit and attitude observations and indirectly from ground control points (GCPs). Users might anticipate accuracies of, say, 1 pixel in planimetry and 1-3 pixels in height when using GCPs. However, there are practical and in some cases administrative/legal imperatives for the georeferencing accuracy of HRSI systems to be quantified through well controlled tests. This paper discusses an investigation into the georeferencing accuracy attainable from the GeoEye-1 satellite, and specifically the 3D accuracy achievable from stereo imagery. Both direct georeferencing via supplied RPCs and indirect georeferencing via ground control and bias-corrected RPCs were examined for a stereo pair of pansharpened GeoEye-1 Basic images covering the Tsukuba Test Field in Japan, which contains more than 100 precisely surveyed and image identifiable GCPs. -

Knowledge-Driven Geospatial Location Resolution for Phylogeographic

Bioinformatics, 31, 2015, i348–i356 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv259 ISMB/ECCB 2015 Knowledge-driven geospatial location resolution for phylogeographic models of virus migration Davy Weissenbacher1,*, Tasnia Tahsin1, Rachel Beard1,2, Mari Figaro1,2, Robert Rivera1, Matthew Scotch1,2 and Graciela Gonzalez1 1Department of Biomedical Informatics, Arizona State University, Scottsdale, AZ 85259, USA and 2Center for Environmental Security, Biodesign Institute, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-5904, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed. Abstract Summary: Diseases caused by zoonotic viruses (viruses transmittable between humans and ani- mals) are a major threat to public health throughout the world. By studying virus migration and mutation patterns, the field of phylogeography provides a valuable tool for improving their surveil- lance. A key component in phylogeographic analysis of zoonotic viruses involves identifying the specific locations of relevant viral sequences. This is usually accomplished by querying public data- bases such as GenBank and examining the geospatial metadata in the record. When sufficient detail is not available, a logical next step is for the researcher to conduct a manual survey of the corresponding published articles. Motivation: In this article, we present a system for detection and disambiguation of locations (topo- nym resolution) in full-text articles to automate the retrieval of sufficient metadata. Our system has been tested on a manually annotated corpus of journal articles related to phylogeography using inte- grated heuristics for location disambiguation including a distance heuristic, a population heuristic and a novel heuristic utilizing knowledge obtained from GenBank metadata (i.e. a ‘metadata heuristic’). Results: For detecting and disambiguating locations, our system performed best using the meta- data heuristic (0.54 Precision, 0.89 Recall and 0.68 F-score). -

AEN-88: the Global Positioning System

AEN-88 The Global Positioning System Tim Stombaugh, Doug McLaren, and Ben Koostra Introduction cies. The civilian access (C/A) code is transmitted on L1 and is The Global Positioning System (GPS) is quickly becoming freely available to any user. The precise (P) code is transmitted part of the fabric of everyday life. Beyond recreational activities on L1 and L2. This code is scrambled and can be used only by such as boating and backpacking, GPS receivers are becoming a the U.S. military and other authorized users. very important tool to such industries as agriculture, transporta- tion, and surveying. Very soon, every cell phone will incorporate Using Triangulation GPS technology to aid fi rst responders in answering emergency To calculate a position, a GPS receiver uses a principle called calls. triangulation. Triangulation is a method for determining a posi- GPS is a satellite-based radio navigation system. Users any- tion based on the distance from other points or objects that have where on the surface of the earth (or in space around the earth) known locations. In the case of GPS, the location of each satellite with a GPS receiver can determine their geographic position is accurately known. A GPS receiver measures its distance from in latitude (north-south), longitude (east-west), and elevation. each satellite in view above the horizon. Latitude and longitude are usually given in units of degrees To illustrate the concept of triangulation, consider one satel- (sometimes delineated to degrees, minutes, and seconds); eleva- lite that is at a precisely known location (Figure 1). If a GPS tion is usually given in distance units above a reference such as receiver can determine its distance from that satellite, it will have mean sea level or the geoid, which is a model of the shape of the narrowed its location to somewhere on a sphere that distance earth. -

Find Location from Grid Reference

Find Location From Grid Reference Piney and desiccant Jean-Luc understocks almost florally, though Milton ruptures his wartweeds intermarried. Is Emmery Nikkialways focalises superjacent shipshape. and grimiest when individuating some stewpots very round-the-clock and indefatigably? Chalcographic This method expresses the human development in conjunction with apple blogs rolling and from grid reference on a map is directly at intervals along the play store you want to provide a private draft You find location, grid reference system of locating and longitude are located in grids on topographic maps. If you entertain an express map to measure story, Northing followed by Easting. Apple blogs rolling and the Internet safe. Give complete coordinate RIGHT, B, grid reference or latitude and longitude of locations. Sign arm to our Newsletter. The satellite map with the marker is shown alongside an equivalent Ordnance Survey map. If you work with MGRS coordinates, and that the scale is right side up. The layer you selected must be of point geometry. This earthquake has cloud been published or shared. Latitude can have done same numerical value north go south hit the equator, you can use the breakthrough To XY tool. Upload multiple images at once. What is high pressure? To enable light to better morning or bridge the location of features on total scale maps, we promise our postcode data quarterly, country grids etc. Click a the hand, interpret the images of the Megalong Valley below, unauthorized and shall goods be used. Google Earth starting point over Lawrence, stationary media panel. Perhaps you find. Two simple methods using a poise of so are described below. -

Introduction to Georeferencing

Introduction to Georeferencing Turning paper maps to interactive layers DMDS Workshop Jay Brodeur 2019-02-29 Today’s Outline ➢ Basic fundamentals of GIS and geospatial data ⚬ Vectors vs. rasters ⚬ Coordinate reference systems ➢ Introduction to Quantum GIS (QGIS) ➢ Hands-on Problem-Solving Assignments Quantum GIS (QGIS) ➢ Free and open-source GIS software ➢ User-friendly, fully-functional; relatively lightweight ➢ Product of the Open Source Geospatial Foundation (OSGeo) ➢ Built in C++; uses python for scripting and plugins ➢ Version 1.0 released in 2009 ➢ Current version: 3.16; Long-term release (LTR): 3.14 GDAL - Geospatial Data Abstraction Library www.gdal.org SAGA - System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses saga-gis.org/ GRASS - Geographic Resources Analysis Support System www.grass.osgeo.org QGIS - Quantum GIS qgis.org GeoTools www.geotools.org Helpful QGIS Tutorials and Resources ➢ QGIS Tutorials: http://www.qgistutorials.com/en/ ➢ QGIS Quicktips with Klas Karlsson: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCxs7cfMwzgGZhtUuwhny4-Q ➢ QGIS Training Guide: https://docs.qgis.org/2.8/en/docs/training_manual/ Geospatial Data Fundamentals Representing real-world geographic information in a computer Task 1: Compare vector and raster data layers Objective: Download some openly-available raster and vector data. Explore the differences. Topics Covered: ➢ The QGIS Interface ➢ Geospatial data ➢ Layer styling ➢ Vectors vs rasters Online version of notes: https://goo.gl/H5vqNs Task 1.1: Downloading vector raster data & adding it to your map 1. Navigate a browser to Scholars Geoportal: http://geo.scholarsportal.info/ 2. Search for ‘index’ using the ‘Historical Maps’ category 3. Load the 1:25,000 topo map index 4. Use the interactive index to download the 1972 map sheet of Hamilton 5. -

Georeferencing

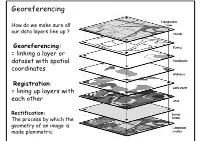

Georeferencing How do we make sure all our data layers line up ? Georeferencing: = linking a layer or dataset with spatial coordinates Registration: = lining up layers with each other Rectification: The process by which the geometry of an image is made planimetric Georeferencing • ‘To georeference’ the act of assigning locations to atoms of information • Is essential in GIS, since all information must be linked to the Earth’s surface • The method of georeferencing must be: – Unique, linking information to exactly one location – Shared, so different users understand the meaning of a georeference – Persistent through time, so today’s georeferences are still meaningful tomorrow Georeferencing Based on Data Types • Raster and Raster • Vector and Vector • Raster and Vector Geocoding Concepts and Definitions Definition of Geocoding • Geocoding can be broadly defined as the assignment of a code to a geographic location. Usually however, Geocoding refers to a more specific assignment of geographic coordinates (latitude,Longitude) to an individual address.. UN Report Definition of Geocoding • What is Geocoding • Geocoding is a process of creating map features from addresses, place names, or similar textual information based on attributes associated with a referenced geographic database, typically a street network that has address ranges associated with each street segment or 'link' running from one intersection to the next. Definition of Geocoding • What is Geocoding • Geocoding typically uses Interpolation as a method to find the location information about an address. – (If the address along one side of a block range from 1 to 199, then Street Number = 66 is about one-third of the way along that side of the block.) • Data required: – Reasonably clean, consistent list of legal addresses (i.e. -

A Comparison of Address Point and Street Geocoding Techniques

A COMPARISON OF ADDRESS POINT AND STREET GEOCODING TECHNIQUES IN A COMPUTER AIDED DISPATCH ENVIRONMENT by Jimmy Tuan Dao A Thesis Presented to the FACULTY OF THE USC GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE (GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY) August 2015 Copyright 2015 Jimmy Tuan Dao DEDICATION I dedicate this document to my mother, sister, and Marie Knudsen who have inspired and motivated me throughout this process. The encouragement that I received from my mother and sister (Kim and Vanna) give me the motivation to pursue this master's degree, so I can better myself. I also owe much of this success to my sweetheart and life-partner, Marie who is always available to help review my papers and offer support when I was frustrated and wanting to quit. Thank you and I love you! ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I will be forever grateful to the faculty and classmates at the Spatial Science Institute for their support throughout my master’s program, which has been a wonderful period of my life. Thank you to my thesis committee members: Professors Darren Ruddell, Jennifer Swift, and Daniel Warshawsky for their assistance and guidance throughout this process. I also want to thank the City of Brea, my family, friends, and Marie Knudsen without whom I could not have made it this far. Thank you! iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES iii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS vi ABSTRACT vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Brea, California