States Reply Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrick Wyrick

AFJ NOMINEE REPORT patrick Wyrick U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma WWW. AFJ.ORG CONTENTS Introduction, 1 Biography, 2 environment, 3 reproductive rights, 6 workers’ Rights, 7 death penalty, 9 Tribal Issues, 9 gun safety, 10 religious bigotry, 10 voting rights, 10 Conclusion, 11 WWW.AFJ.ORG PAGE 1 reproductive health, helped dismantle protections for workers, defended a Introduction law that attempted to codify religious intolerance toward Muslims, and even On April 10, 2018, President Trump came under fire for allegedly nominated Oklahoma Supreme Court attempting to mislead the U.S. Justice Patrick Wyrick to the U.S. Supreme Court during his defense of District Court for the Western District Oklahoma’s death penalty protocol. of Oklahoma. If confirmed, Wyrick, Wyrick’s nomination is in keeping with who is just 37 years old and has the Trump Administration’s stated practiced law for just over ten years, goal of filling the federal bench with will replace Judge David Russell, who judges who are hostile to government assumed senior status on July 7, 2013.1 regulations that protect health and Patrick Wyrick is also on President safety, the environment, consumers Trump’s short list for the Supreme and workers, having once stated, “I Court. think we have all sorts of basic Despite his short legal career, Wyrick fundamental Constitutional problems has made a name for himself as a with the nature of the current 2 protégé of current Environmental administrative state.” Protection Agency (EPA) As the Senate Judiciary Committee Administrator Scott Pruitt, for whom reviews Wyrick’s controversial he worked during Pruitt’s tenure as positions and activities during Oklahoma Attorney General. -

OEA 2018 Election Guide

OEA 2018 Election Guide Read the full responses from all participating candidates at okea.org/legislative. 1 2018 Election Guide: Table of Contents State Senate Page 7 State House of Representatives Page 30 Statewide Elections Page 107 Congress Page 117 Judicial Elections Page 123 State Questions Page 127 Candidate Recommendaitons Page 133 Need help? Contact your regional team. The Education Focus (ISSN 1542-1678) Oklahoma City Metro, Northwest, Southeast is published quarterly for $5 and Southwest Teams by the Oklahoma Education Association, The Digital Education Focus 323 E. Madison, Okla. City, OK 73105 323 E. Madison, Oklahoma City, OK 73105. 800/522-8091 or 405/528-7785 Periodicals postage paid at Okla. City, OK, Volume 35, No. 4 and additional mailing offices. The Education Focus is a production Northeast and Tulsa Metro Teams POSTMASTER: Send address changes of the Oklahoma Education Association’s 10820 E. 45th , Suite. 110, Tulsa, OK, 74146 to The Education Focus, PO Box 18485, Communications Center. 800/331-5143 or 918/665-2282 Oklahoma City, OK 73154. Alicia Priest, President Katherine Bishop, Vice President Join the conversation. David DuVall, Executive Director okea.org Amanda Ewing, Associate Executive Director Facebook – Oklahoma.Education.Association Doug Folks, Editor and Student.Oklahoma.Education.Association Bill Guy, Communications twitter.com/okea (@okea) Carrie Coppernoll Jacobs, Social Media instagram.com/insta_okea Jacob Tharp, Center Assistant pinterest.com/oeaedupins Read the full responses from all participating candidates at okea.org/legislative. 2 2018 Election Guide Now is the time to persevere Someone once said that “Perseverance is the hard work you do after you get tired of the hard work you already did.” NOW is the time to roll up our sleeves, dig in, and persevere! When walkout at the apitol was over, I stood in a press conference with my colleagues and announced that what we didn’t gain this legislative session, we would next gain in the next. -

Petitioners, V

NO. In the Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF OKLAHOMA; OKLAHOMA INDUSTRIAL ENERGY CONSUMERS; OKLAHOMA GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY, Petitioners, v. UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY; SIERRA CLUB, Respondents. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI Michael Graves E. Scott Pruitt Thomas P. Schroedter Oklahoma Attorney General HALL ESTILL, Patrick R. Wyrick Attorneys at Law Solicitor General 320 South Boston Ave. Counsel of Record Suite 200 P. Clayton Eubanks Tulsa, OK 74103 Deputy Solicitor General (918) 594-0443 OKLAHOMA ATTORNEY GENERALS OFFICE Attorneys for Petitioner 313 NE 21st Street Oklahoma Industrial Oklahoma City, OK 73105 Energy Consumers (405) 521-3921 [email protected] Attorneys for Petitioner State of Oklahoma (additional counsel listed on inside cover) Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 Brian J. Murray Charles T. Wehland Dennis Murashko JONES DAY 77 West Wacker Drive Chicago, IL 60601 (312) 782-3939 Michael L. Rice JONES DAY 717 Texas, Suite 3300 Houston, TX 77002 (832) 239-3640 Attorneys for Petitioner Oklahoma Gas And Electric Company i QUESTION PRESENTED The Regional Haze Program of the Clean Air Act allocates to the States the task of fashioning and then implementing plans to improve the aesthetic quality of air over certain federal lands. The question presented is whether, despite that allocation of powers to the States, the United States Environmental Protection Agency may nonetheless conduct a de novo review of the State of Oklahomas plan, in conflict with both the limited authority granted to the agency under the Act and decisions of this and other courts that have recognized the primary role given to the States in implementing the Clean Air Act. -

Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2019 Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations Carl Tobias University of Richmond - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Carl Tobias, Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations, 104 Iowa L. Rev. Online 31 (2019). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CARL_PDF PROOF FINAL 12.1.2019 FONT FIX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/4/2019 2:15 PM Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations Carl Tobias* I. 2015–16 PROCESSES ....................................................................... 33 A. THE 2015–16 DISTRICT COURT PROCESSES ............................... 34 1. The Nomination Process ................................................ 34 2. The Confirmation Process .............................................. 36 i. Committee Hearings ..................................................... 36 ii. Committee Votes ........................................................... 37 iii. Floor Votes ................................................................... 38 B. THE 2015–16 APPELLATE COURT PROCESSES ........................... -

Oklahoma Bar Journal 753 754 the Oklahoma Bar Journal Vol

ALSO INSIDE • Fair Debt Collection Practices Act • Juvenile Court • Members Celebrate Significant Anniversaries ALSO INSIDE • Fair Debt Collection Practices Act • Juvenile Court • Members Celebrate Significant Anniversaries The New Lawyer Experience: Hit the Ground Running Oklahoma City • April 30th OPENING A BUSINESS TRUST ACCOUNTING & LEGAL ETHICS • Resources for starting a law practice • The role of OBA Ethics Counsel • Being an employee versus the business owner • The role of OBA General Counsel • Business entity selection • Most common questions of the Ethics Counsel • Physical location/practice setting options • Trustworthy Trust Accounts • Liability insurance and other aspects of risk management • File and document retention • Business planning • Ethical issues facing small firm lawyers Jim Calloway, Director,OBAManagementAssistance • Simple guidelines for ethical conduct Program,OklahomaCity • Ethics resources • Q&A MANAGEMENT - MANAGING YOUR FINANCES, GinaHendryx,OBAEthicsCounsel,OklahomaCity YOUR FILES, AND YOUR STAFF • Profit, loss, and the importance of good financial reports MARKETING • Establishing practice areas • Developing a marketing plan • Setting fees • Ethical marketing strategies • The importance of building work flow systems and tracking • Differences in marketing vs. public relations work in progress • Budgeting - Marketing on a tight budget or no budget • Client file management • Generating referrals - Word of mouth is your best • Billing (retainers, mechanics of billing, “alternative billing,” marketing tool getting -

Amicus Brief

No. 14-284 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- WILLIAM HUMBLE, Director of the Arizona Department of Health Services, in his official capacity, Petitioner, v. PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF ARIZONA, INC.; WILLIAM RICHARDSON, M.D., dba TUCSON WOMEN’S CENTER; WILLIAM H. RICHARDSON, M.D., P.C., dba TUCSON WOMEN’S CENTER, Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF OKLAHOMA, NEBRASKA, SOUTH CAROLINA, ALASKA, IDAHO, MONTANA, MICHIGAN, AND TEXAS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER --------------------------------- --------------------------------- E. SCOTT PRUITT Attorney General of Oklahoma PATRICK R. WYRICK* Solicitor General OKLAHOMA ATTORNEY GENERAL’S OFFICE 313 N.E. 21st Street Oklahoma City, OK 73105 (405) 522-4448 (405) 522-4534 FAX [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae State of Oklahoma *Counsel of Record [Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM JON BRUNING GREG ABBOTT Attorney General Attorney General STATE OF NEBRASKA STATE OF TEXAS 2115 State Capitol P.O. Box 12548 Lincoln, NE 68509 Austin, TX 78711 ALAN WILSON Attorney General STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA P.O. Box 11549 Columbia, SC 29211 MICHAEL C. GERAGHTY Attorney General STATE OF ALASKA P.O. Box 110300 Juneau, AK 99811 LAWRENCE G. WASDEN Attorney General STATE OF IDAHO P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720 TIMOTHY C. FOX Attorney General STATE OF MONTANA 215 N. Sanders Helena, MT 59620 BILL SCHUETTE Attorney General STATE OF MICHIGAN P.O. Box 30212 Lansing, MI 48909 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF THE IDENTITY, INTEREST, AND AUTHORITY OF AMICUS TO FILE ...... -

United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

UNITED STATES SENATE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY QUESTIONNAIRE FOR JUDICIAL NOMINEES PUBLIC 1. Name: State full name (include any former names used). Patrick Robert Wyrick 2. Position: State the position for which you have been nominated. United States District Judge for the Western District of Oklahoma 3. Address: List current office address. If city and state ofresidence differs from your place of employment, please list the city and state where you currently reside. Oklahoma Supreme Court Oklahoma Judicial Center, Room N222 2100 North Lincoln Boulevard Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73105 I live and work in Oklahoma City, but I consider my place of permanent residency to be my hometown of Atoka, Oklahoma. 4. Birthplace: State year and place of birth. 1981; Denison, Texas 5. Education: List in reverse chronological order each college, law school, or any other institution of higher education attended and indicate for each the dates of attendance, whether a degree was received, and the date each degree was received. 2004 -2007, University of Oklahoma College of Law; J.D., 2007 1999 - 2000, 2002 - 2004, University of Oklahoma; B.A., 2004 2001 - 2002, Oklahoma City University; no degree received 2001, Cowley County Community College; no degree received 6. Employment Record: List in reverse chronological order all governmental agencies, business or professional corporations, companies, firms, or other enterprises, paiinerships, institutions or organizations, non-profit or otherwise, with which you have been affiliated as an officer, director, partner, proprietor, or employee since graduation from college, whether or not you received payment for your services. Include the name and address of the employer and job title or description. -

Schell Amended Complaint

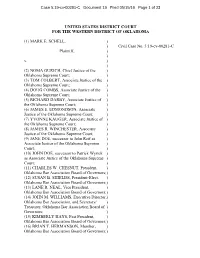

Case 5:19-cv-00281-C Document 19 Filed 05/15/19 Page 1 of 23 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA (1) MARK E. SCHELL, ) ) Civil Case No. 5:19-cv-00281-C Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) (2) NOMA GURICH, Chief Justice of the ) Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (3) TOM COLBERT, Associate Justice of the ) Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (4) DOUG COMBS, Associate Justice of the ) Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (5) RICHARD DARBY, Associate Justice of ) the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (6) JAMES E. EDMONDSON, Associate ) Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (7) YVONNE KAUGER, Associate Justice of ) the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (8) JAMES R. WINCHESTER, Associate ) Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (9) JANE DOE, successor to John Reif as ) Associate Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme ) Court; ) (10) JOHN DOE, successor to Patrick Wyrick ) as Associate Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme ) Court; ) (11) CHARLES W. CHESNUT, President, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (12) SUSAN B. SHIELDS, President-Elect, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (13) LANE R. NEAL, Vice President, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (14) JOHN M. WILLIAMS, Executive Director,) Oklahoma Bar Association, and Secretary/ ) Treasurer, Oklahoma Bar Association Board of ) Governors; ) (15) KIMBERLY HAYS, Past President, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (16) BRIAN T. HERMANSON, Member, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) Case 5:19-cv-00281-C Document 19 Filed 05/15/19 Page 2 of 23 (17) MARK E. FIELDS, Member, Oklahoma ) Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (18) DAVID T. MCKENZIE, Member, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (19) TIMOTHY E. DECLERCK, Member ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (20) ANDREW E. -

Robin Fretwell Wilson

ROBIN FRETWELL WILSON University of Illinois 19 Fields East College of Law Champaign, Illinois 61822 504 East Pennsylvania Avenue Cell (540) 958-1389 Champaign, Illinois 61820 [email protected] Tel. (217) 244-1227 Robinfretwellwilson.org Fax (217) 244-1478 Robinfretwellwilson.com TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2013 – Present University of Illinois College of Law, Champaign, Illinois Roger and Stephany Joslin Professor of Law and Director, Family Law and Policy Program (2013 – Present) Director, Epstein Program in Health Law and Policy (2016 – Present) Director, Fairness For All Initiative supported by the Templeton Religion Trust and the First Amendment Partnership through directed gifts (2016 – Present) Director, Tolerance Means Dialogues supported by directed gifts (2016 – Present) Director, Substance Abuse and Addiction Affinity Group, Institute for Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois System Professor, Department of Pathology, University of Illinois College of Medicine Urbana- Champaign (2016 – Present) Teaching areas include: biomedical ethics; children’s health, violence and the law; family law; seminar on tolerance. University service: Provost’s Named Faculty Appointment Committee (2013 – 2017). Law school service: Admissions Committee (2014 – 2015); Faculty Retreat Co-Chair (2014 – 2015); Student scholarship committee (2013 – 2014, 2015 – 2016, Chair, 2017 – 2018); Chairs and Professorship Committee (2016 – 2017); Clerkship Committee, Chair, 2018 – 2019). 2007 – 2013 Washington and Lee University School of Law, Lexington, Virginia Class of 1958 Law Alumni Professor of Law (2009 – 2013) and Law Alumni Faculty Fellow (2011 – 2012) Professor of Law and Law Alumni Faculty Fellow (2008 – 2009) Professor of Law (2007 – 2013) Director and Founder, Johnson & Johnson Law and Medicine Colloquium (2008 – 2013) Teaching areas included: family law; seminar on children, culture and violence; law and social science seminar; advanced family law practicum; health law practicum; insurance. -

July Briefcase

JULY 2014 Vol. 46, No. 7 A Publication of the OKLAHOMA COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION WWW.OKCBAR.ORG OCBA 2014 OCBA Award recipients include: Awards Luncheon A Success for All Robert H. Gilliland, Professional Service Award Edward & Tom Goldman, Goldman Law Firm, Don Holladay & James Warner, Jr., Pro Bono Award Community Service Award Ages President Patricia Parrish greeted, pre- sented awards and entertained a crowd of over 250 at this year’s Annual Award Luncheon on June 20 at the Tower Hotel. Past President and Awards Committee Chair John Heatly assisted in the presentation of this year’s OCBA awards. The 50- and 60- year OBA Service Awards were handed out to the recipients by the Honorable Tom Colbert, Chief Justice of the Oklahoma Gretchen Harris, Chair of Lawyers Against Editor Geary Walke presents the Briefcase Award to Charles Geister accepted the Bobby G. Knapp Supreme Court, and M. Joe Crosthwait, Past Domestic Abuse Committee Alissa Shaddix White Leadership Award on behalf of Laura McConnell- OBA and OCBA President. Corbyn Seth Day, President’s Courageous Lawyer Award; YLD Chair Drew Mildren presents the Outstanding Dawn Rahme, representing the firm of Phillips Judge Lisa Hammond, YLD Beacon Award Susanna Gattoni was also a recipient of this award, YLD Director Award to Curtis Thomas Murrah, received the YLD Friends of the Young but was unable to attend Lawyers Award See AWARDS, PAGE 16 Inside Profiles in OCBA Golf From The President . .2 Work Life Balance. .6 In Remembrance: Book Notes. .8 Professionalism Tournament Judge David M. Cook . .3 Bar Observer . .13 Glimpse at Attorney Edward A. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, APRIL 2, 2019 No. 57 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was midst of low commodity prices, unfair immigrant communities across New called to order by the Speaker pro tem- trade prices, labor shortages, and con- Jersey and across this country. pore (Mr. BUTTERFIELD). secutive years of storms now had relief Earlier this month, the New Jersey Policy Perspective issued a report con- f in sight. Then entered Hurricane Mi- chael, and it was all gone in a matter firming something we have known for a DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO of hours. Not just the commodity crops long time in my district and in New TEMPORE like cotton, but the orchards, too. Jersey: immigrants continue to serve The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- Since day one post-Hurricane Mi- as the backbone of Main Street. fore the House the following commu- chael, I have worked side by side with Immigrants make up 22 percent of nication from the Speaker: my friend and my colleague, Congress- the total State population, and immi- man SANFORD BISHOP. Hurricane Mi- grants own 47 percent of Main Street WASHINGTON, DC, chael didn’t discriminate between our businesses. Immigrant communities April 2, 2019. I hereby appoint the Honorable G.K. district lines. I want to thank him for own 81 percent of household mainte- BUTTERFIELD to act as Speaker pro tempore his help and his support of our State nance services, 79 percent of laundry on this day. -

Will Rogers 1 2 Sample Ballots Employers Give You Time

“Sitting on the shores of life throwing our little pebbles in the great ocean of human events . making ripples. trying to grasp the opportunity to promote human progress regardless of personal risk or sacrifice.” —KATE BARNARD “We may elevate ourselves but we should never reach so high that we would ever forget those who helped us get there.” —WILL ROGERS 1 2 SAMPLE BALLOTS EMPLOYERS GIVE YOU TIME By the end of September, individualized Oklahoma employers must provide sample ballots are available on the State employees with up to two hours of paid Election Board website, elections. ok.gov. time to vote on Election Day, unless their County election boards provide sample shifts give them plenty of time to do so ballots, too. before or after work. You must notify your employer of your intention to vote at least one day before the election. STAY IN THE KNOW 3 REGISTRATION DEADLINE Fri., Oct. 12. You can download a registration STEPS form from the State Election Board website or pick one up at your county election TO INCREASE YOUR board, post offices, tag agencies, libraries, VOTING PROWESS and other public locations. You will need to mail or deliver the completed form to your county election board. MORE INFORMATION: The State Election Board website is a 4 5 good place to start: elections.ok.gov. NOTE WHEN YOU VOTE SWITCHING PARTIES For information about the candidates and the state questions, check out You may bring written notes to your You can change your party affiliation or www.vote411.org, Oklahomawatch.org polling place, but don’t show them register as an independent until Fri., Oct.