Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 15, 2012 Primary Election

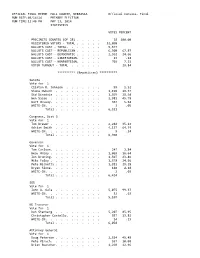

OFFICIAL RESULTS HALL COUNTY, NEBRASKA Canvas-Election Final RUN DATE:05/18/12 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:01 PM MAY 15, 2012 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 28) . 28 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 31,173 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 7,633 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 5,219 68.37 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 2,045 26.79 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 4 .05 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 355 4.65 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 24.49 ********** (Republican) ********** President of the United States Vote for 1 Newt Gingrich . 293 Ron Paul. 449 Mitt Romney. 3,406 Rick Santorum . 796 WRITE-IN. 57 Total . 5,001 United States Senator Vote for 1 Spencer Zimmerman. 29 Don Stenberg . 865 Jon Bruning. 1,669 Deb Fischer. 2,540 Pat Flynn . 121 Sharyn Elander. 28 WRITE-IN. 15 Total . 5,267 Representative in Congress Vote for 1 Adrian Smith . 3,975 Bob Lingenfelter . 1,180 WRITE-IN. 14 Total . 5,169 Hall County Public Defender Vote for 1 Gerard A. Piccolo. 4,144 WRITE-IN. 38 Total . 4,182 Hall County Supervisor Dist 2 Vote for 1 Daniel Purdy . 855 WRITE-IN. 5 Total . 860 Hall County Supervisor Dist 4 Vote for 1 Pamela Lancaster . 426 WRITE-IN. 7 Total . 433 Hall County Supervisor Dist 6 Vote for 1 Gary Quandt. 231 Robert M. Humiston, Jr.. 119 WRITE-IN. 2 Total . 352 ********** (Democratic) ********** President of the United States Vote for 1 Barack Obama . 1,447 WRITE-IN. 169 Total . 1,616 United States Senator Vote for 1 Larry Marvin . 64 Steven P. Lustgarten. 50 Sherman Yates . 32 Chuck Hassebrook . -

Research Report: Nebraska Pilot Test

6.1 Nebraska pilot test Effective Designs for the Administration of Federal Elections Section 6: Research report: Nebraska pilot test June 2007 U.S. Election Assistance Commission 6.2 Nebraska pilot test Nebraska pilot test overview Preparing for an election can be a challenging, complicated process for election offi cials. Production cycles are organized around state-mandated deadlines that often leave narrow windows for successful content development, certifi cation, translations, and election design activities. By keeping election schedules tightly controlled and making uniform voting technology decisions for local jurisdictions, States aspire to error-free elections. Unfortunately, current practices rarely include time or consideration for user-centered design development to address the basic usability needs of voters. As a part of this research effort, a pilot study was conducted using professionally designed voter information materials and optical scan ballots in two Nebraska counties on Election Day, November 7, 2006. A research contractor partnered with Nebraska’s Secretary of State’s Offi ce and their vendor, Elections Systems and Software (ES&S), to prepare redesigned materials for Colfax County and Cedar County (Lancaster County, originally included, opted out of participation). The goal was to gauge overall design success with voters and collaborate with experienced professionals within an actual production cycle with all its variables, time lines, and participants. This case study reports the results of voter feedback on election materials, observations, and interviews from Election Day, and insights from a three-way attempt to utilize best practice design conventions. Data gathered in this study informs the fi nal optical scan ballot and voter information specifi cations in sections 2 and 3 of the best practices documentation. -

Final RUN DATE:05/16/14 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:46 PM MAY 13, 2014 STATISTICS

OFFICIAL FINAL REPOR HALL COUNTY, NEBRASKA Official Canvass- Final RUN DATE:05/16/14 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:46 PM MAY 13, 2014 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 28) . 28 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 32,090 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 9,577 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 6,500 67.87 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 2,362 24.66 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 13 .14 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 702 7.33 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 29.84 ********** (Republican) ********** Senate Vote for 1 Clifton R. Johnson . 99 1.52 Shane Osborn . 1,196 18.37 Sid Dinsdale . 1,865 28.64 Ben Sasse . 2,981 45.78 Bart McLeay. 367 5.64 WRITE-IN. 3 .05 Total . 6,511 Congress, Dist 3 Vote for 1 Tom Brewer . 2,244 35.12 Adrian Smith . 4,137 64.74 WRITE-IN. 9 .14 Total . 6,390 Governor Vote for 1 Tom Carlson. 247 3.84 Beau McCoy . 1,069 16.64 Jon Bruning. 1,507 23.46 Mike Foley . 1,578 24.56 Pete Ricketts . 1,881 29.28 Bryan Slone. 140 2.18 WRITE-IN. 2 .03 Total . 6,424 SOS Vote for 1 John A. Gale . 5,075 99.37 WRITE-IN. 32 .63 Total . 5,107 NE Tresurer Vote for 1 Don Stenberg . 5,207 85.95 Christopher Costello. 837 13.82 WRITE-IN. 14 .23 Total . 6,058 Attorney General Vote for 1 Doug Peterson . 2,514 45.48 Pete Pirsch. 557 10.08 Brian Buescher. 1,269 22.96 Mike Hilgers . 1,183 21.40 WRITE-IN. 5 .09 Total . 5,528 State Auditor Vote for 1 Charlie Janssen . -

Patrick Wyrick

AFJ NOMINEE REPORT patrick Wyrick U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma WWW. AFJ.ORG CONTENTS Introduction, 1 Biography, 2 environment, 3 reproductive rights, 6 workers’ Rights, 7 death penalty, 9 Tribal Issues, 9 gun safety, 10 religious bigotry, 10 voting rights, 10 Conclusion, 11 WWW.AFJ.ORG PAGE 1 reproductive health, helped dismantle protections for workers, defended a Introduction law that attempted to codify religious intolerance toward Muslims, and even On April 10, 2018, President Trump came under fire for allegedly nominated Oklahoma Supreme Court attempting to mislead the U.S. Justice Patrick Wyrick to the U.S. Supreme Court during his defense of District Court for the Western District Oklahoma’s death penalty protocol. of Oklahoma. If confirmed, Wyrick, Wyrick’s nomination is in keeping with who is just 37 years old and has the Trump Administration’s stated practiced law for just over ten years, goal of filling the federal bench with will replace Judge David Russell, who judges who are hostile to government assumed senior status on July 7, 2013.1 regulations that protect health and Patrick Wyrick is also on President safety, the environment, consumers Trump’s short list for the Supreme and workers, having once stated, “I Court. think we have all sorts of basic Despite his short legal career, Wyrick fundamental Constitutional problems has made a name for himself as a with the nature of the current 2 protégé of current Environmental administrative state.” Protection Agency (EPA) As the Senate Judiciary Committee Administrator Scott Pruitt, for whom reviews Wyrick’s controversial he worked during Pruitt’s tenure as positions and activities during Oklahoma Attorney General. -

Inside This Issue

River Crossings - Volume 17 - Number 1 - January/February 2008 River Crossings - Volume 17 - Number 1 - January/February 2008 Volume 17 January/February 2008 Number 1 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Reader’s Survey diversion project in Mississippi’s Yazoo But the Corps maintains that the project pro- River Basin carries a $220 million price tag vides vital flood protection and an economic It’s been some time since we conducted and has the potential to destroy as much as boost for a region that desperately needs it. our last Reader’s Survey, and with a new 200,000 acres of bottomland forest and other And the project’s powerful congressional Coordinator coming onboard patron, Sen. Thad Cochran soon, we felt it appropriate to of Mississippi, the Senate’s ask our readers for input as to top Republican appropriator, how we’ve been doing. So shares the Corps’ view. In please take a few moments of fact, Cochran has helped pro- your time to provide feed- vide about $50 million over back on the enclosed form or the years to get the project send a note by return email to back on the Corps’ drawing [email protected]. As always, board. your input will help River Crossings remain focused View of seasonally flooded bottomland hardwood forest in the Pearl River In a statement, Cochran and meeting your needs in Basin, Louisiana and Mississippi. (Louisiana State University Photo.) called the project “the last keeping you abreast of impor- leg” in a long-sought flood tant natural resource issues in control plan for his state, not- the Mississippi River Basin. -

Throwback Issue - 6 the X-Change Is Celebrating Its 50Th Year

May 9, 2014 Volume 50 Issue 8 XchangePius X High School 6000 A Street, Lincoln, NE Wordstruck Live - 8 Students performed and read their works, and 'best ofs' were announced. Senior Xposed - 4 Kenny Nyguen is a really chill senior who likes to dance and travel. Throwback Issue - 6 The X-Change is celebrating its 50th year. PHOTOS BY ANNIE ALBIN 2 News May 9, 2014 Primary election day draws near Pinnacle Bank Arena tion on healthcare policy and previous comments NICK ESPARZA ends season in the red Sports Editor on the issue, and he has also raised questions about Sasse’s ties to the state. This year’s basketball Major stakes are involved in Nebraska’s On the other hand however, the gubernato- HAYLEE DILTZ season really took a toll on Republican primary, with national tea party groups rial race has been heating up as well. Staff Writer the arena as well. State bas- and figures backing Republican Ben Sasse as their With 6 people running for governor, the ketball back in February put a best hope for a Senate victory this election season. competition has stiffened up to take control of the The new Pinnacle halt on concerts and big events, Urgent: Should Obamacare Be Repealed? popular vote. Bank Arena is in the red causing the arena to lose a lot Vote Here Now! Specifically, two canidates have been spar- due to its income loss. more money than expected. With most of the senior class being of age to ring for the lead. The Pinnacle Bank The city of Lincoln is vote, the up and coming primary election is just the Omaha businessman Pete Ricketts and Arena is an indoor arena in said not to have been responsible start of their influence in politics. -

2014 Official Primary Election Results

PRIMARY ELECTION RESULTS SENATORIAL TICKET For Attorney General For United States Senator 4 Year Term 6 Year Term Republican Republican Doug Peterson 317 Clifton R. Johnson 15 Pete Pirsch 63 Shane Osborn 255 Brian Buescher 372 Sid Dinsdale 216 Mike Hilgers 155 Ben Sasse 484 Democrat Bart McLeay 73 Janet Stewart 197 Democrat Allan J. Eurek 96 Larry Marvin 127 Libertarian Dave Domina 171 No Filings Libertarian No Filings For Auditor of Public Accounts 4 Year Term CONGRESSIONAL TICKET Republican For Representative in Congress Charlie Janssen 394 District 3 Larry Anderson 364 2 Year Term Democrat Republican Amanda McGill 262 Tom Brewer 222 Libertarian Adrian Smith 799 No Filings Democrat Mark Sullivan 262 COUNTY TICKET Libertarian For County Board of Supervisors No Filings District 5 4 Year Term STATE TICKET Republican PARTISAN Steven D. Yates 78 For Governor Susan L. Johnson 83 4 Year Term Democrat Republican No Filings Tom Carlson 36 Libertarian Beau McCoy 208 No Filings Jon Bruning 338 Mike Foley 234 STATE TICKET Pete Ricketts 210 NON-PARTISAN Bryan Slone 20 For Member of the Legislature Democrat District 32 Chuck Hassebrook 288 4 Year Term Libertarian Laura Ebke 7220 Mark G. Elworth Jr. 0 Phil Hardenburger 536 For Secretary of State For Member State Board of Education 4 Year Term District 5 Republican 4 Year Term John A. Gale 864 Patricia Timm 564 Democrat Christine Lade 454 No Filings Libertarian For Member of the Board of Regents Ben Backus 0 University of Nebraska District 5 For State Treasurer 4 Year Term 4 Year Term Rob Schafer 367 Republican Steve Glenn 459 Don Stenberg 821 Robert J. -

OEA 2018 Election Guide

OEA 2018 Election Guide Read the full responses from all participating candidates at okea.org/legislative. 1 2018 Election Guide: Table of Contents State Senate Page 7 State House of Representatives Page 30 Statewide Elections Page 107 Congress Page 117 Judicial Elections Page 123 State Questions Page 127 Candidate Recommendaitons Page 133 Need help? Contact your regional team. The Education Focus (ISSN 1542-1678) Oklahoma City Metro, Northwest, Southeast is published quarterly for $5 and Southwest Teams by the Oklahoma Education Association, The Digital Education Focus 323 E. Madison, Okla. City, OK 73105 323 E. Madison, Oklahoma City, OK 73105. 800/522-8091 or 405/528-7785 Periodicals postage paid at Okla. City, OK, Volume 35, No. 4 and additional mailing offices. The Education Focus is a production Northeast and Tulsa Metro Teams POSTMASTER: Send address changes of the Oklahoma Education Association’s 10820 E. 45th , Suite. 110, Tulsa, OK, 74146 to The Education Focus, PO Box 18485, Communications Center. 800/331-5143 or 918/665-2282 Oklahoma City, OK 73154. Alicia Priest, President Katherine Bishop, Vice President Join the conversation. David DuVall, Executive Director okea.org Amanda Ewing, Associate Executive Director Facebook – Oklahoma.Education.Association Doug Folks, Editor and Student.Oklahoma.Education.Association Bill Guy, Communications twitter.com/okea (@okea) Carrie Coppernoll Jacobs, Social Media instagram.com/insta_okea Jacob Tharp, Center Assistant pinterest.com/oeaedupins Read the full responses from all participating candidates at okea.org/legislative. 2 2018 Election Guide Now is the time to persevere Someone once said that “Perseverance is the hard work you do after you get tired of the hard work you already did.” NOW is the time to roll up our sleeves, dig in, and persevere! When walkout at the apitol was over, I stood in a press conference with my colleagues and announced that what we didn’t gain this legislative session, we would next gain in the next. -

Petitioners, V

NO. In the Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF OKLAHOMA; OKLAHOMA INDUSTRIAL ENERGY CONSUMERS; OKLAHOMA GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY, Petitioners, v. UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY; SIERRA CLUB, Respondents. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI Michael Graves E. Scott Pruitt Thomas P. Schroedter Oklahoma Attorney General HALL ESTILL, Patrick R. Wyrick Attorneys at Law Solicitor General 320 South Boston Ave. Counsel of Record Suite 200 P. Clayton Eubanks Tulsa, OK 74103 Deputy Solicitor General (918) 594-0443 OKLAHOMA ATTORNEY GENERALS OFFICE Attorneys for Petitioner 313 NE 21st Street Oklahoma Industrial Oklahoma City, OK 73105 Energy Consumers (405) 521-3921 [email protected] Attorneys for Petitioner State of Oklahoma (additional counsel listed on inside cover) Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 Brian J. Murray Charles T. Wehland Dennis Murashko JONES DAY 77 West Wacker Drive Chicago, IL 60601 (312) 782-3939 Michael L. Rice JONES DAY 717 Texas, Suite 3300 Houston, TX 77002 (832) 239-3640 Attorneys for Petitioner Oklahoma Gas And Electric Company i QUESTION PRESENTED The Regional Haze Program of the Clean Air Act allocates to the States the task of fashioning and then implementing plans to improve the aesthetic quality of air over certain federal lands. The question presented is whether, despite that allocation of powers to the States, the United States Environmental Protection Agency may nonetheless conduct a de novo review of the State of Oklahomas plan, in conflict with both the limited authority granted to the agency under the Act and decisions of this and other courts that have recognized the primary role given to the States in implementing the Clean Air Act. -

Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2019 Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations Carl Tobias University of Richmond - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Carl Tobias, Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations, 104 Iowa L. Rev. Online 31 (2019). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CARL_PDF PROOF FINAL 12.1.2019 FONT FIX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/4/2019 2:15 PM Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations Carl Tobias* I. 2015–16 PROCESSES ....................................................................... 33 A. THE 2015–16 DISTRICT COURT PROCESSES ............................... 34 1. The Nomination Process ................................................ 34 2. The Confirmation Process .............................................. 36 i. Committee Hearings ..................................................... 36 ii. Committee Votes ........................................................... 37 iii. Floor Votes ................................................................... 38 B. THE 2015–16 APPELLATE COURT PROCESSES ........................... -

Primary Election Official Results

OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF STATE CANVASSERS OF THE STATE OF NEBRASKA PRIMARY ELECTION MAY 13, 2014 Compiled by JOHN A. GALE, Nebraska Secretary of State Page 2 Reported Problems York County/Upper Big Blue NRD Subdistrict 4 The Upper Big Blue NRD utilizes an election process where candidates file for office by Subdistrict (based on their residence), but the voters in the NRD vote on all subdistricts (at large). Due to a misreading of the certification from the NRD, the York County Clerk only put the race on ballots in the precincts in Subdistrict 4. The error was discovered midmorning on the day of election and ballots containing the Subdistrict 4 candidates were delivered to the polling sites in an attempt to mitigate the error. However, even with the corrective action, 1,056 York County voters did not receive the Subdistrict 4 ballot. The results of the election indicate that Stan Boehr received 3422 votes, Eugene Ulmer received 2870 votes and Becky Roesler received 2852 votes. With the margin between Mr. Ulmer and Ms. Roesler at 18 votes, the error impacted the outcome of the election. During the automatic recount of the race, it was discovered that the supplemental ballots delivered to the polling sites were not initialed by pollworkers as required by statute and were not counted during the recount process. Following the recount, the results indicate that Mr. Boehr received 3,004 votes, Ms. Roesler received 2,563 votes and Mr. Ulmer received 2,539 votes. Page 3 Official Results of Nebraska Primary Election May 13, 2014 Table of Contents VOTING STATISTICS......................................................................................................................................................... -

Oklahoma Bar Journal 753 754 the Oklahoma Bar Journal Vol

ALSO INSIDE • Fair Debt Collection Practices Act • Juvenile Court • Members Celebrate Significant Anniversaries ALSO INSIDE • Fair Debt Collection Practices Act • Juvenile Court • Members Celebrate Significant Anniversaries The New Lawyer Experience: Hit the Ground Running Oklahoma City • April 30th OPENING A BUSINESS TRUST ACCOUNTING & LEGAL ETHICS • Resources for starting a law practice • The role of OBA Ethics Counsel • Being an employee versus the business owner • The role of OBA General Counsel • Business entity selection • Most common questions of the Ethics Counsel • Physical location/practice setting options • Trustworthy Trust Accounts • Liability insurance and other aspects of risk management • File and document retention • Business planning • Ethical issues facing small firm lawyers Jim Calloway, Director,OBAManagementAssistance • Simple guidelines for ethical conduct Program,OklahomaCity • Ethics resources • Q&A MANAGEMENT - MANAGING YOUR FINANCES, GinaHendryx,OBAEthicsCounsel,OklahomaCity YOUR FILES, AND YOUR STAFF • Profit, loss, and the importance of good financial reports MARKETING • Establishing practice areas • Developing a marketing plan • Setting fees • Ethical marketing strategies • The importance of building work flow systems and tracking • Differences in marketing vs. public relations work in progress • Budgeting - Marketing on a tight budget or no budget • Client file management • Generating referrals - Word of mouth is your best • Billing (retainers, mechanics of billing, “alternative billing,” marketing tool getting