Halbig, Et Al., Appellants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 15, 2012 Primary Election

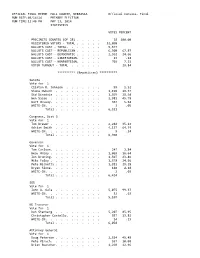

OFFICIAL RESULTS HALL COUNTY, NEBRASKA Canvas-Election Final RUN DATE:05/18/12 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:01 PM MAY 15, 2012 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 28) . 28 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 31,173 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 7,633 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 5,219 68.37 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 2,045 26.79 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 4 .05 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 355 4.65 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 24.49 ********** (Republican) ********** President of the United States Vote for 1 Newt Gingrich . 293 Ron Paul. 449 Mitt Romney. 3,406 Rick Santorum . 796 WRITE-IN. 57 Total . 5,001 United States Senator Vote for 1 Spencer Zimmerman. 29 Don Stenberg . 865 Jon Bruning. 1,669 Deb Fischer. 2,540 Pat Flynn . 121 Sharyn Elander. 28 WRITE-IN. 15 Total . 5,267 Representative in Congress Vote for 1 Adrian Smith . 3,975 Bob Lingenfelter . 1,180 WRITE-IN. 14 Total . 5,169 Hall County Public Defender Vote for 1 Gerard A. Piccolo. 4,144 WRITE-IN. 38 Total . 4,182 Hall County Supervisor Dist 2 Vote for 1 Daniel Purdy . 855 WRITE-IN. 5 Total . 860 Hall County Supervisor Dist 4 Vote for 1 Pamela Lancaster . 426 WRITE-IN. 7 Total . 433 Hall County Supervisor Dist 6 Vote for 1 Gary Quandt. 231 Robert M. Humiston, Jr.. 119 WRITE-IN. 2 Total . 352 ********** (Democratic) ********** President of the United States Vote for 1 Barack Obama . 1,447 WRITE-IN. 169 Total . 1,616 United States Senator Vote for 1 Larry Marvin . 64 Steven P. Lustgarten. 50 Sherman Yates . 32 Chuck Hassebrook . -

Research Report: Nebraska Pilot Test

6.1 Nebraska pilot test Effective Designs for the Administration of Federal Elections Section 6: Research report: Nebraska pilot test June 2007 U.S. Election Assistance Commission 6.2 Nebraska pilot test Nebraska pilot test overview Preparing for an election can be a challenging, complicated process for election offi cials. Production cycles are organized around state-mandated deadlines that often leave narrow windows for successful content development, certifi cation, translations, and election design activities. By keeping election schedules tightly controlled and making uniform voting technology decisions for local jurisdictions, States aspire to error-free elections. Unfortunately, current practices rarely include time or consideration for user-centered design development to address the basic usability needs of voters. As a part of this research effort, a pilot study was conducted using professionally designed voter information materials and optical scan ballots in two Nebraska counties on Election Day, November 7, 2006. A research contractor partnered with Nebraska’s Secretary of State’s Offi ce and their vendor, Elections Systems and Software (ES&S), to prepare redesigned materials for Colfax County and Cedar County (Lancaster County, originally included, opted out of participation). The goal was to gauge overall design success with voters and collaborate with experienced professionals within an actual production cycle with all its variables, time lines, and participants. This case study reports the results of voter feedback on election materials, observations, and interviews from Election Day, and insights from a three-way attempt to utilize best practice design conventions. Data gathered in this study informs the fi nal optical scan ballot and voter information specifi cations in sections 2 and 3 of the best practices documentation. -

Final RUN DATE:05/16/14 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:46 PM MAY 13, 2014 STATISTICS

OFFICIAL FINAL REPOR HALL COUNTY, NEBRASKA Official Canvass- Final RUN DATE:05/16/14 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:46 PM MAY 13, 2014 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 28) . 28 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 32,090 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 9,577 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 6,500 67.87 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 2,362 24.66 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 13 .14 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 702 7.33 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 29.84 ********** (Republican) ********** Senate Vote for 1 Clifton R. Johnson . 99 1.52 Shane Osborn . 1,196 18.37 Sid Dinsdale . 1,865 28.64 Ben Sasse . 2,981 45.78 Bart McLeay. 367 5.64 WRITE-IN. 3 .05 Total . 6,511 Congress, Dist 3 Vote for 1 Tom Brewer . 2,244 35.12 Adrian Smith . 4,137 64.74 WRITE-IN. 9 .14 Total . 6,390 Governor Vote for 1 Tom Carlson. 247 3.84 Beau McCoy . 1,069 16.64 Jon Bruning. 1,507 23.46 Mike Foley . 1,578 24.56 Pete Ricketts . 1,881 29.28 Bryan Slone. 140 2.18 WRITE-IN. 2 .03 Total . 6,424 SOS Vote for 1 John A. Gale . 5,075 99.37 WRITE-IN. 32 .63 Total . 5,107 NE Tresurer Vote for 1 Don Stenberg . 5,207 85.95 Christopher Costello. 837 13.82 WRITE-IN. 14 .23 Total . 6,058 Attorney General Vote for 1 Doug Peterson . 2,514 45.48 Pete Pirsch. 557 10.08 Brian Buescher. 1,269 22.96 Mike Hilgers . 1,183 21.40 WRITE-IN. 5 .09 Total . 5,528 State Auditor Vote for 1 Charlie Janssen . -

Inside This Issue

River Crossings - Volume 17 - Number 1 - January/February 2008 River Crossings - Volume 17 - Number 1 - January/February 2008 Volume 17 January/February 2008 Number 1 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Reader’s Survey diversion project in Mississippi’s Yazoo But the Corps maintains that the project pro- River Basin carries a $220 million price tag vides vital flood protection and an economic It’s been some time since we conducted and has the potential to destroy as much as boost for a region that desperately needs it. our last Reader’s Survey, and with a new 200,000 acres of bottomland forest and other And the project’s powerful congressional Coordinator coming onboard patron, Sen. Thad Cochran soon, we felt it appropriate to of Mississippi, the Senate’s ask our readers for input as to top Republican appropriator, how we’ve been doing. So shares the Corps’ view. In please take a few moments of fact, Cochran has helped pro- your time to provide feed- vide about $50 million over back on the enclosed form or the years to get the project send a note by return email to back on the Corps’ drawing [email protected]. As always, board. your input will help River Crossings remain focused View of seasonally flooded bottomland hardwood forest in the Pearl River In a statement, Cochran and meeting your needs in Basin, Louisiana and Mississippi. (Louisiana State University Photo.) called the project “the last keeping you abreast of impor- leg” in a long-sought flood tant natural resource issues in control plan for his state, not- the Mississippi River Basin. -

Throwback Issue - 6 the X-Change Is Celebrating Its 50Th Year

May 9, 2014 Volume 50 Issue 8 XchangePius X High School 6000 A Street, Lincoln, NE Wordstruck Live - 8 Students performed and read their works, and 'best ofs' were announced. Senior Xposed - 4 Kenny Nyguen is a really chill senior who likes to dance and travel. Throwback Issue - 6 The X-Change is celebrating its 50th year. PHOTOS BY ANNIE ALBIN 2 News May 9, 2014 Primary election day draws near Pinnacle Bank Arena tion on healthcare policy and previous comments NICK ESPARZA ends season in the red Sports Editor on the issue, and he has also raised questions about Sasse’s ties to the state. This year’s basketball Major stakes are involved in Nebraska’s On the other hand however, the gubernato- HAYLEE DILTZ season really took a toll on Republican primary, with national tea party groups rial race has been heating up as well. Staff Writer the arena as well. State bas- and figures backing Republican Ben Sasse as their With 6 people running for governor, the ketball back in February put a best hope for a Senate victory this election season. competition has stiffened up to take control of the The new Pinnacle halt on concerts and big events, Urgent: Should Obamacare Be Repealed? popular vote. Bank Arena is in the red causing the arena to lose a lot Vote Here Now! Specifically, two canidates have been spar- due to its income loss. more money than expected. With most of the senior class being of age to ring for the lead. The Pinnacle Bank The city of Lincoln is vote, the up and coming primary election is just the Omaha businessman Pete Ricketts and Arena is an indoor arena in said not to have been responsible start of their influence in politics. -

2014 Official Primary Election Results

PRIMARY ELECTION RESULTS SENATORIAL TICKET For Attorney General For United States Senator 4 Year Term 6 Year Term Republican Republican Doug Peterson 317 Clifton R. Johnson 15 Pete Pirsch 63 Shane Osborn 255 Brian Buescher 372 Sid Dinsdale 216 Mike Hilgers 155 Ben Sasse 484 Democrat Bart McLeay 73 Janet Stewart 197 Democrat Allan J. Eurek 96 Larry Marvin 127 Libertarian Dave Domina 171 No Filings Libertarian No Filings For Auditor of Public Accounts 4 Year Term CONGRESSIONAL TICKET Republican For Representative in Congress Charlie Janssen 394 District 3 Larry Anderson 364 2 Year Term Democrat Republican Amanda McGill 262 Tom Brewer 222 Libertarian Adrian Smith 799 No Filings Democrat Mark Sullivan 262 COUNTY TICKET Libertarian For County Board of Supervisors No Filings District 5 4 Year Term STATE TICKET Republican PARTISAN Steven D. Yates 78 For Governor Susan L. Johnson 83 4 Year Term Democrat Republican No Filings Tom Carlson 36 Libertarian Beau McCoy 208 No Filings Jon Bruning 338 Mike Foley 234 STATE TICKET Pete Ricketts 210 NON-PARTISAN Bryan Slone 20 For Member of the Legislature Democrat District 32 Chuck Hassebrook 288 4 Year Term Libertarian Laura Ebke 7220 Mark G. Elworth Jr. 0 Phil Hardenburger 536 For Secretary of State For Member State Board of Education 4 Year Term District 5 Republican 4 Year Term John A. Gale 864 Patricia Timm 564 Democrat Christine Lade 454 No Filings Libertarian For Member of the Board of Regents Ben Backus 0 University of Nebraska District 5 For State Treasurer 4 Year Term 4 Year Term Rob Schafer 367 Republican Steve Glenn 459 Don Stenberg 821 Robert J. -

Primary Election Official Results

OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF STATE CANVASSERS OF THE STATE OF NEBRASKA PRIMARY ELECTION MAY 13, 2014 Compiled by JOHN A. GALE, Nebraska Secretary of State Page 2 Reported Problems York County/Upper Big Blue NRD Subdistrict 4 The Upper Big Blue NRD utilizes an election process where candidates file for office by Subdistrict (based on their residence), but the voters in the NRD vote on all subdistricts (at large). Due to a misreading of the certification from the NRD, the York County Clerk only put the race on ballots in the precincts in Subdistrict 4. The error was discovered midmorning on the day of election and ballots containing the Subdistrict 4 candidates were delivered to the polling sites in an attempt to mitigate the error. However, even with the corrective action, 1,056 York County voters did not receive the Subdistrict 4 ballot. The results of the election indicate that Stan Boehr received 3422 votes, Eugene Ulmer received 2870 votes and Becky Roesler received 2852 votes. With the margin between Mr. Ulmer and Ms. Roesler at 18 votes, the error impacted the outcome of the election. During the automatic recount of the race, it was discovered that the supplemental ballots delivered to the polling sites were not initialed by pollworkers as required by statute and were not counted during the recount process. Following the recount, the results indicate that Mr. Boehr received 3,004 votes, Ms. Roesler received 2,563 votes and Mr. Ulmer received 2,539 votes. Page 3 Official Results of Nebraska Primary Election May 13, 2014 Table of Contents VOTING STATISTICS......................................................................................................................................................... -

Amicus Brief

No. 14-284 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- WILLIAM HUMBLE, Director of the Arizona Department of Health Services, in his official capacity, Petitioner, v. PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF ARIZONA, INC.; WILLIAM RICHARDSON, M.D., dba TUCSON WOMEN’S CENTER; WILLIAM H. RICHARDSON, M.D., P.C., dba TUCSON WOMEN’S CENTER, Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF OKLAHOMA, NEBRASKA, SOUTH CAROLINA, ALASKA, IDAHO, MONTANA, MICHIGAN, AND TEXAS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER --------------------------------- --------------------------------- E. SCOTT PRUITT Attorney General of Oklahoma PATRICK R. WYRICK* Solicitor General OKLAHOMA ATTORNEY GENERAL’S OFFICE 313 N.E. 21st Street Oklahoma City, OK 73105 (405) 522-4448 (405) 522-4534 FAX [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae State of Oklahoma *Counsel of Record [Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM JON BRUNING GREG ABBOTT Attorney General Attorney General STATE OF NEBRASKA STATE OF TEXAS 2115 State Capitol P.O. Box 12548 Lincoln, NE 68509 Austin, TX 78711 ALAN WILSON Attorney General STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA P.O. Box 11549 Columbia, SC 29211 MICHAEL C. GERAGHTY Attorney General STATE OF ALASKA P.O. Box 110300 Juneau, AK 99811 LAWRENCE G. WASDEN Attorney General STATE OF IDAHO P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720 TIMOTHY C. FOX Attorney General STATE OF MONTANA 215 N. Sanders Helena, MT 59620 BILL SCHUETTE Attorney General STATE OF MICHIGAN P.O. Box 30212 Lansing, MI 48909 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF THE IDENTITY, INTEREST, AND AUTHORITY OF AMICUS TO FILE ...... -

STEALTH DONORS Outside Groups Spent More Than $1 Billion Trying to Influence the 2012 Elections. Nearly Two- Thirds of That

STEALTH DONORS Outside groups spent more than $1 billion trying to influence the 2012 elections. Nearly two- thirds of that money flowed through super PACs – groups able to raise unlimited contributions. Super PACs got a lot of attention this year, but despite that, some seven-figure donors managed to avoid the spotlight. Now, new research by Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) sheds light on a dozen super PAC donors who gave at least $1 million, but whose efforts to sway votes drew little attention. The bipartisan list of big-money donors includes the family behind a popcorn empire, a businessman whose mining companies have been cited for a long list of environmental problems, an advertising industry leader, and a real estate developer who leases space to government agencies. All had policy or business interests depending on the outcome of the elections. The Supreme Court’s disastrous Citizens United decision unleashed an onslaught of outside spending, though in many cases this year, it wasn’t enough to sweep preferred candidates into office. Nonetheless, super PAC donors with millions of dollars at their disposal and a demonstrated willingness to spend their money on politics are likely to get special attention from lawmakers. The only question remaining is, what sort of return are these donors expecting on their investments? Philip Geier, Jr., consultant and former advertising executive. From: New York, NY Total Super PAC Donations: $1.35 million American Crossroads (R): $1 million Restore Our Future, Inc. (R): $350,000 Total Other Political Donations: $207,800 Republicans: $53,400 o Presidential candidate Mitt Romney: $2,500 o Rep. -

Lifting Leaders to the Throne Of

Lifting Leaders to the Throne of God Lifting Leaders to the Throne of God I urge you that first of all intercession and thanksgiving be made for those in I urge you that first of all intercession and thanksgiving be made for those in authority so you might live peaceful and quiet lives. authority so you might live peaceful and quiet lives. II Timothy 2:1- 2 II Timothy 2:1- 2 Nebraska State Senators Nebraska State Senators Annette Dubas Beau McCoy Annette Dubas Beau McCoy Tommy Garrett Amanda McGill Tommy Garrett Amanda McGill Greg L. Adams Mike Gloor Heath Mello Greg L. Adams Mike Gloor Heath Mello Brad Ashford Ken Haar John Murante Brad Ashford Ken Haar John Murante Bill Avery Galen Hadley John Nelson Bill Avery Galen Hadley John Nelson Dave Bloomfield Tom Hansen Jeremy Nordquist Dave Bloomfield Tom Hansen Jeremy Nordquist Kate Bolz John Harms Pete Pirsch Kate Bolz John Harms Pete Pirsch Lydia Brasch Burke Harr Jim Scheer Lydia Brasch Burke Harr Jim Scheer Cathy Campbell Sara Howard Ken Schilz Cathy Campbell Sara Howard Ken Schilz Tom Carlson Charlie Janssen Paul Schumacher Tom Carlson Charlie Janssen Paul Schumacher Ernie Chambers Jerry Johnson Les Seiler Ernie Chambers Jerry Johnson Les Seiler Mark Christensen Russ Karpisek Jim Smith Mark Christensen Russ Karpisek Jim Smith Colby Coash Bill Kintner Kate Sullivan Colby Coash Bill Kintner Kate Sullivan Danielle Conrad Bob Krist Norman Wallman Danielle Conrad Bob Krist Norman Wallman Tanya Cook Tyson Larson Dan Watermeier Tanya Cook Tyson Larson Dan Watermeier Sue Crawford Steve Lathrop John Wightman Sue Crawford Steve Lathrop John Wightman Al Davis Scott Lautenbaugh Al Davis Scott Lautenbaugh Governor Dave Heineman Governor Dave Heineman & & Lieutenant Governor Lavon Heidemann Lieutenant Governor Lavon Heidemann Governor’s Cabinet Governor’s Cabinet Dr. -

7 W|3:,G VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL

NEBRASKA REPUBLICAN PARTY Mark Fahleson, Chairman 251/0^-7 W|3:,g VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL October 4,2011 Mr. Anthony Herman, Esq. General Counsel Federal Election Commission 999 E Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20463 COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Dear Mr. Herman: The Nebraska Republican Party files this complaint seeking an inunediate investigation into the Nebraska Democratic State Central Conunittee's C*NDSCC") and Senator Ben Nelson's illegal spending practices. Their conununications and public records show, and an investigation will confirm that the NDSCC and Senator Nelson have engaged in a massive spending spree in an attempt to prop up and resuscitate Senator Nelson's re-election campaign. NDSCC has made, and Senator Nelson has accepted, expenditures to benefit Senator Nelson's re-election campaign in violation ofthe Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended (tiie "Act"), 2 U.S.C. §§ 431 etseq. and Federal Election Conunission ("FEC") regulations, 11 C.F.R. §§ 100.1 etseq. FACTS Nebraska's two term Democratic Senator's re-election campaign is in desperate shape. The Senator's long history of being out of step with Nebraska - culminating in the infiunous "Comhusker Kickback," the deal with which the Obama Administration effectively bought Senator Nelson's 60^ vote for Obamacare - has chiseled his re-election number in the 30% range. The Democrats' hold on a Senate majority is also in desperate shape. The party is defending 23 seats in a year when the American, public is angry with Congress and frustrated with President Obama's failed economic policies. Nebraska is a "must win" state for the Democratic Party in 2012. -

Appendix a Fort Randall Dam/ Lake Francis Case Project South Dakota Surplus Water Report Environmental Assessment

US Army Corps of Engineers Omaha District Draft Fort Randall Dam/Lake Francis Case Project South Dakota Surplus Water Report Volume 1 Surplus Water Report Appendix A – Environmental Assessment August 2012 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK FORT RANDALL DAM/LAKE FRANCIS CASE PROJECT SOUTH DAKOTA SURPLUS WATER REPORT Omaha District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers August 2012 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Fort Randall Dam/Lake Francis Case, South Dakota FORT RANDALL DAM/LAKE FRANCIS CASE, SOUTH DAKOTA SURPLUS WATER REPORT August 2012 Prepared By: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District Omaha, NE Abstract: The Omaha District is proposing to temporarily make available 27,973 acre-feet/year of surplus water (equivalent to 71,890 acre-feet of storage) from the system-wide irrigation storage available at the Fort Randall Dam/Lake Francis Case Project, South Dakota to meet municipal and industrial (M&I) water supply needs. Under Section 6 of the Flood Control Act of 1944 (Public Law 78-534), the Secretary of the Army is authorized to make agreements with states, municipalities, private concerns, or individuals for surplus water that may be available at any reservoir under the control of the Department. Terms of the agreements are normally for five (5) years, with an option for a five (5) year extension, subject to recalculation of reimbursement after the initial five (5) year period. This proposed action will allow the Omaha District to enter into surplus water agreements with interested water purveyors and to issue easements for up to the total amount of surplus water to meet regional water needs.