Phenology and Function in Lycopod-Mucoromycotina Symbiosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RI Equisetopsida and Lycopodiopsida.Indd

IIntroductionntroduction byby FFrancisrancis UnderwoodUnderwood Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida and Isoetopsida Special Th anks to the following for giving permission for the use their images. Robbin Moran New York Botanical Garden George Yatskievych and Ann Larson Missouri Botanical Garden Jan De Laet, plantsystematics.org Th is pdf is a companion publication to Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida & Isoetopsida at among-ri-wildfl owers.org Th e Elfi n Press 2016 Introduction Formerly known as fern allies, Horsetails, Club-mosses, Fir-mosses, Spike-mosses and Quillworts are plants that have an alternate generation life-cycle similar to ferns, having both sporophyte and gametophyte stages. Equisetopsida Horsetails date from the Devonian period (416 to 359 million years ago) in earth’s history where they were trees up to 110 feet in height and helped to form the coal deposits of the Carboniferous period. Only one genus has survived to modern times (Equisetum). Horsetails Horsetails (Equisetum) have jointed stems with whorls of thin narrow leaves. In the sporophyte stage, they have a sterile and fertile form. Th ey produce only one type of spore. While the gametophytes produced from the spores appear to be plentiful, the successful reproduction of the sporophyte form is low with most Horsetails reproducing vegetatively. Lycopodiopsida Lycopodiopsida includes the clubmosses (Dendrolycopodium, Diphasiastrum, Lycopodiella, Lycopodium , Spinulum) and Fir-mosses (Huperzia) Clubmosses Clubmosses are evergreen plants that produce only microspores that develop into a gametophyte capable of producing both sperm and egg cells. Club-mosses can produce the spores either in leaf axils or at the top of their stems. Th e spore capsules form in a cone-like structures (strobili) at the top of the plants. -

Characterization of Two Undescribed Mucoralean Species with Specific

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 26 March 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201803.0204.v1 1 Article 2 Characterization of Two Undescribed Mucoralean 3 Species with Specific Habitats in Korea 4 Seo Hee Lee, Thuong T. T. Nguyen and Hyang Burm Lee* 5 Division of Food Technology, Biotechnology and Agrochemistry, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, 6 Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea; [email protected] (S.H.L.); 7 [email protected] (T.T.T.N.) 8 * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-(0)62-530-2136 9 10 Abstract: The order Mucorales, the largest in number of species within the Mucoromycotina, 11 comprises typically fast-growing saprotrophic fungi. During a study of the fungal diversity of 12 undiscovered taxa in Korea, two mucoralean strains, CNUFC-GWD3-9 and CNUFC-EGF1-4, were 13 isolated from specific habitats including freshwater and fecal samples, respectively, in Korea. The 14 strains were analyzed both for morphology and phylogeny based on the internal transcribed 15 spacer (ITS) and large subunit (LSU) of 28S ribosomal DNA regions. On the basis of their 16 morphological characteristics and sequence analyses, isolates CNUFC-GWD3-9 and CNUFC- 17 EGF1-4 were confirmed to be Gilbertella persicaria and Pilobolus crystallinus, respectively.To the 18 best of our knowledge, there are no published literature records of these two genera in Korea. 19 Keywords: Gilbertella persicaria; Pilobolus crystallinus; mucoralean fungi; phylogeny; morphology; 20 undiscovered taxa 21 22 1. Introduction 23 Previously, taxa of the former phylum Zygomycota were distributed among the phylum 24 Glomeromycota and four subphyla incertae sedis, including Mucoromycotina, Kickxellomycotina, 25 Zoopagomycotina, and Entomophthoromycotina [1]. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Seed Plant Models

Review Tansley insight Why we need more non-seed plant models Author for correspondence: Stefan A. Rensing1,2 Stefan A. Rensing 1 2 Tel: +49 6421 28 21940 Faculty of Biology, University of Marburg, Karl-von-Frisch-Str. 8, 35043 Marburg, Germany; BIOSS Biological Signalling Studies, Email: stefan.rensing@biologie. University of Freiburg, Sch€anzlestraße 18, 79104 Freiburg, Germany uni-marburg.de Received: 30 October 2016 Accepted: 18 December 2016 Contents Summary 1 V. What do we need? 4 I. Introduction 1 VI. Conclusions 5 II. Evo-devo: inference of how plants evolved 2 Acknowledgements 5 III. We need more diversity 2 References 5 IV. Genomes are necessary, but not sufficient 3 Summary New Phytologist (2017) Out of a hundred sequenced and published land plant genomes, four are not of flowering plants. doi: 10.1111/nph.14464 This severely skewed taxonomic sampling hinders our comprehension of land plant evolution at large. Moreover, most genetically accessible model species are flowering plants as well. If we are Key words: Charophyta, evolution, fern, to gain a deeper understanding of how plants evolved and still evolve, and which of their hornwort, liverwort, moss, Streptophyta. developmental patterns are ancestral or derived, we need to study a more diverse set of plants. Here, I thus argue that we need to sequence genomes of so far neglected lineages, and that we need to develop more non-seed plant model species. revealed much, the exact branching order and evolution of the I. Introduction nonbilaterian lineages is still disputed (Lanna, 2015). Research on animals has for a long time relied on a number of The first (small) plant genome to be sequenced was of THE traditional model organisms, such as mouse, fruit fly, zebrafish or model plant, the weed Arabidopsis thaliana (c. -

Supplementary Table S2: New Taxonomic Assignment of Sequences of Basal Fungal Lineages

Supplementary Table S2: New taxonomic assignment of sequences of basal fungal lineages. Fungal sequences were subjected to BLAST-N analysis and checked for their taxonomic placement in the eukaryotic guide-tree of the SILVA release 111. Sequences were classified depending on combined results from the methods mentioned above as well as literature searches. Accession Name New classification Clustering of the sequence in the Best BLAST-N hit number based on combined results eukaryotic guide tree of SILVA Name Accession number E.value Identity AB191431 Uncultured fungus Chytridiomycota Chytridiomycota Basidiobolus haptosporus AF113413.1 0.0 91 AB191432 Unculltured eukaryote Blastocladiomycota Blastocladiomycota Rhizophlyctis rosea NG_017175.1 0.0 91 AB252775 Uncultured eukaryote Chytridiomycota Chytridiomycota Blastocladiales sp. EF565163.1 0.0 91 AB252776 Uncultured eukaryote Fungi Nucletmycea_Fonticula Rhizophydium sp. AF164270.2 0.0 87 AB252777 Uncultured eukaryote Chytridiomycota Chytridiomycota Basidiobolus haptosporus AF113413.1 0.0 91 AB275063 Uncultured fungus Chytridiomycota Chytridiomycota Catenomyces sp. AY635830.1 0.0 90 AB275064 Uncultured fungus Chytridiomycota Chytridiomycota Endogone lactiflua DQ536471.1 0.0 91 AB433328 Nuclearia thermophila Nuclearia Nucletmycea_Nuclearia Nuclearia thermophila AB433328.1 0.0 100 AB468592 Uncultured fungus Basal clone group I Chytridiomycota Physoderma dulichii DQ536472.1 0.0 90 AB468593 Uncultured fungus Basal clone group I Chytridiomycota Physoderma dulichii DQ536472.1 0.0 91 AB468594 Uncultured -

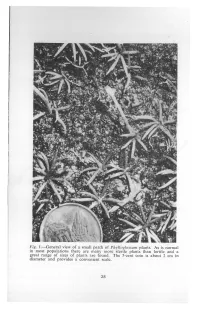

General View of a Small Patch of Phylloglossum Plants. As Is Normal

. Fig. 1- General view of a small patch of Phylloglossum plants. As is normal in most populations there are many more sterile plants than fertile and a great range of sizes of plants are found. The 5-cent coin is about 2 cm in diameter and provides a convenient scale. 28 Phylloglossum Miniature Denizen of the North /. E. Braggins, Auckland Phylloglossum drummondii, first described by Kunze, a German botanist, in 1843, is a very small plant related to the lycopodiums or club mosses. In addition to New Zealand it is found in Western Australia, Tasmania, and Victoria. There is only one species of Phylloglossum, and because of its small size and habit of growing in low sedge and scrub it is not often detected. Furthermore it has a short growing season when it is above ground (May-June till September-October), and few botanists know it in the field. The description in Allan's Flora of New Zealand tells us that it is "... a plant up to 5 cm long, rarely more; leaves linear, acute, usually few, seldom more than 10, about 2 cm long". The stalk or peduncle of the fruiting part is described as 3-4 cm long, with a strobilus (sport-bearing part) about 7 mm long. The generic description having already said that the strobilus was terminal and roots scanty, we have some idea what the plant may look like, though words cannot convey adequately the appearance of this unusual little plant (Fig. 1). In New Zealand Phylloglossum is often regarded as a typical kauri and burnt-over scrubland plant. -

Effects of Lycopodium Clavatum and Equisetum Arvense Extracts from Western Romania

Romanian Biotechnological Letters Vol. , No. x, Copyright © 2016 University of Bucharest Printed in Romania. All rights reserved ORIGINAL PAPER Effects of Lycopodium clavatum and equisetum arvense extracts from western Romania Received for publication, July, 07, 2014 Accepted, October, 13, 2015 MARIA SUCIU1, FELIX AUREL MIC1, LUCIAN BARBU-TUDORAN2, VASILE MUNTEAN2, ALEXANDRA TEODORA GRUIA3,* 1University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Victor Babes”, Department of Functional Sciences, Timisoara, 2, Eftimie Murgu Sq., Timisoara, 300041, Timis County, Romania 2Babes-Bolyai University, Biology and Geology Department, 5-7 Clinicilor Str., Cluj-Napoca, 400084, Cluj County, Romania. 3Emergency Clinical County Hospital Timisoara, Regional Centre for Transplant Immunology Department, 10, Iosif Bulbuca Blvd., Timisoara, 300736, Timis County, Romania. *Address for correspondence to: [email protected], 10, Iosif Bulbuca Blvd., Timisoara, 300736, Timis County, Romania. Abbreviations: ALT–alanin transaminases, AST–aspartate transaminases, GC-MS–gas chromatograph coupled with mass spectrometry. Abstract Plants have always excited interest because of their active principles that could be a source of healing in various affections. The aim of this study was to demonstrate that the hepatoprotective and antimicrobial effects of Lycopodium clavatum and Equisetum arvense from the Western parts of Romania (Arad County) are not as pronounced as described in literature, against xenobiotic intoxication or microbial infection. To identify the plants active compounds, -

Fungal Evolution: Major Ecological Adaptations and Evolutionary Transitions

Biol. Rev. (2019), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12510 Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions Miguel A. Naranjo-Ortiz1 and Toni Gabaldon´ 1,2,3∗ 1Department of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Dr. Aiguader 88, Barcelona 08003, Spain 2 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08003 Barcelona, Spain 3ICREA, Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT Fungi are a highly diverse group of heterotrophic eukaryotes characterized by the absence of phagotrophy and the presence of a chitinous cell wall. While unicellular fungi are far from rare, part of the evolutionary success of the group resides in their ability to grow indefinitely as a cylindrical multinucleated cell (hypha). Armed with these morphological traits and with an extremely high metabolical diversity, fungi have conquered numerous ecological niches and have shaped a whole world of interactions with other living organisms. Herein we survey the main evolutionary and ecological processes that have guided fungal diversity. We will first review the ecology and evolution of the zoosporic lineages and the process of terrestrialization, as one of the major evolutionary transitions in this kingdom. Several plausible scenarios have been proposed for fungal terrestralization and we here propose a new scenario, which considers icy environments as a transitory niche between water and emerged land. We then focus on exploring the main ecological relationships of Fungi with other organisms (other fungi, protozoans, animals and plants), as well as the origin of adaptations to certain specialized ecological niches within the group (lichens, black fungi and yeasts). -

An Approach to the Problem of Taxonomy and Classification in the Study of Sporae Dispersae

AN APPROACH TO THE PROBLEM OF TAXONOMY AND CLASSIFICATION IN THE STUDY OF SPORAE DISPERSAE D. C. BHARDWAJ Birbal~i Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow ABSTRACT ( 1950 ) system, the American workers prefer The present state of disagreement among spore that of Schopf, Wilson and Bentall's ( 1944), workers with regard to the taxonomy and classi• in Germany, an amplification of Ibrahim's fication of Sporae dispersae has been reviewed. ( 1933) system is mostly in vogue and the The taxonomic categories for Sporae dispersae have Russian workers classify according to Nau• been defined and practicability of organ-genus concept over the form-genus concept for the circum• mova's (1937) system. This tendency to scription of spore taxa has been discussed. stick to one or the other of these systems, none of which excels the others, has uncons• ciously led to thwart the evolution of one such INTRODUCTION system of classification for the Sporae dis• persae which may be universally followed. Of late, in view of the greater applied use of DETAILEDand pollen,studyrecoveredof the dispersedfrom sedimen•spores Sporae dispersae in coal and oil prospecting, tary strata, dates back to Reinsch the need for a universally accepted standard ( 1881) when he described some of them from system of classification for these is being coals of the Carboniferous age. Thereafter, increasingly felt so that assimilation of data for several decades, these dispersed micro• from all over the world can be more easily remains attracted occasional attention of achieved. palaeobotanists -

Introduction to Botany. Lecture 31

Questions and answers Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Introduction to Botany. Lecture 31 Alexey Shipunov Minot State University November 16, 2011 Shipunov BIOL 154.31 Questions and answers Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Outline 1 Questions and answers 2 Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Bryophyta: mosses Shipunov BIOL 154.31 Questions and answers Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Outline 1 Questions and answers 2 Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Bryophyta: mosses Shipunov BIOL 154.31 2 Questions and answers Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Previous final question: the answer 1 Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh 2 Citrus 3 Piperaceae Where is a genus name? Shipunov BIOL 154.31 Questions and answers Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Previous final question: the answer 1 Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh 2 Citrus 3 Piperaceae Where is a genus name? 2 Shipunov BIOL 154.31 Questions and answers Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Results of Exam 3 (statistical summary) Summary: Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. NA’s 43.00 67.00 79.00 78.36 92.00 108.00 5.00 Grades: F D C B max 61 72 82 92 102 Shipunov BIOL 154.31 Questions and answers Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Results of Exam 3 (the curve) Density estimation for Exam 3 (Biol 154) 61 92 (F) (B) Points Shipunov BIOL 154.31 Questions and answers Bryophyta: mosses Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Bryophyta: mosses Shipunov BIOL 154.31 Questions and answers Bryophyta: mosses Kingdom Vegetabilia: plants Three main phyla Bryophyta: gametophyte predominance Pteridophyta: sporophyte predominance, no seed Spermatophyta: -

(Lycopodiaceae) in the State of Veracruz, Mexico

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.8 (1): 114-137, 2015 Research article Distribution and conservation status of Phlegmariurus (Lycopodiaceae) in the state of Veracruz, Mexico Samaria Armenta-Montero1, César I. Carvajal-Hernández1, Edward A. Ellis1 and Thorsten Krömer1* 1Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales, Universidad Veracruzana, Casco de la Ex Hacienda Lucas Martín, Privada de Araucarias S/N. Col. Periodistas, C.P. 91019, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract The fern and lycophyte flora of Mexico contains 13 species in the genus Phlegmariurus (Lycopodiaceae; club moss family), of which nine are found in the state of Veracruz (P. cuernavacensis, P. dichotomus, P. linifolius, P. myrsinites, P. orizabae, P. pithyoides, P. pringlei, P. reflexus , P. taxifolius). They are located primarily in undisturbed areas of humid montane, pine-oak and tropical humid forests, which are all ecosystems threatened by deforestation and fragmentation. The objective of this study was to evaluate and understand the distribution and conservation status of species of this genus in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Using Maxent, probability distributions were modeled based on 173 herbarium specimens (25% from recent collections by the authors and/or collaborators), considering factors such as climate, elevation and vegetation cover. Additionally, anthropogenic impacts on the original habitat of each species were analyzed in order to assign threatened categories based on IUCN classifications at regional levels. Results show that potential distributions are located in the montane regions of the central and southern parts of the state. All nine Phlegmariurus species in Veracruz were found to be in some category of risk, with P. -

Chapter 23: the Early Tracheophytes

Chapter 23 The Early Tracheophytes THE LYCOPHYTES Lycopodium Has a Homosporous Life Cycle Selaginella Has a Heterosporous Life Cycle Heterospory Allows for Greater Parental Investment Isoetes May Be the Only Living Member of the Lepidodendrid Group THE MONILOPHYTES Whisk Ferns Ophioglossalean Ferns Horsetails Marattialean Ferns True Ferns True Fern Sporophytes Typically Have Underground Stems Sexual Reproduction Usually Is Homosporous Fern Have a Variety of Alternative Means of Reproduction Ferns Have Ecological and Economic Importance SUMMARY PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Sporophyte Prominence and Survival on Land PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Coal, Smog, and Forest Decline THE OCCUPATION OF THE LAND PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE The First Tracheophytes Were ENVIRONMENT: Diversity Among the Ferns Rhyniophytes Tracheophytes Became Increasingly Better PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Adapted to the Terrestrial Environment ENVIRONMENT: Fern Spores Relationships among Early Tracheophytes 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. Tracheophytes, also called vascular plants, possess lignified water-conducting tissue (xylem). Approximately 14,000 species of tracheophytes reproduce by releasing spores and do not make seeds. These are sometimes called seedless vascular plants. Tracheophytes differ from bryophytes in possessing branched sporophytes that are dominant in the life cycle. These sporophytes are more tolerant of life on dry land than those of bryophytes because water movement is controlled by strongly lignified vascular tissue, stomata, and an extensive cuticle. The gametophytes, however still require a seasonally wet habitat, and water outside the plant is essential for the movement of sperm from antheridia to archegonia. 2. The rhyniophytes were the first tracheophytes. They consisted of dichotomously branching axes, lacking roots and leaves. They are all extinct.