Download (1629Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016 / 17

Annual Report 2016 / 17 BMT_Annual Report 16/17.indd 1 03/11/2017 10:39 Reflecting Birmingham to the World, & the World to Birmingham Registered Charity Number: 1147014 Cover image © 2016 Christie’s Images Limited. Image p.24 © Vanley Burke. BMT_Annual Report 16/17.indd 2 03/11/2017 10:39 02 – 03 Birmingham Museums Trust is an independent CONTENTS educational charity formed in 2012. 04 CHAIR’S FOREWORD It cares for Birmingham’s internationally important collection of over 800,000 objects 05 DIRECTOR’S INTRODUCTION which are stored and displayed in nine unique venues including six Listed Buildings and one 06 OUR ACHIEVEMENTS Scheduled Ancient Monument. 08 AUDIENCES Birmingham Museums Trust is a company limited by guarantee. 12 SUPPORTERS 14 VENUES 15 Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery 16 Aston Hall 17 Blakesley Hall 18 Museum of the Jewellery Quarter 19 Sarehole Mill 20 Soho House 21 Thinktank Science Museum 22 Museum Collection Centre 23 Weoley Castle 24 COLLECTIONS 26 CURATORIAL 28 MAKING IT HAPPEN 30 TRADING 31 DEVELOPMENT 32 FINANCES 35 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 36 TALKS AND LECTURES BMT_Annual Report 16/17.indd 3 03/11/2017 10:39 Chair’s foreword Visitor numbers exceeded one million for the It is with pleasure that third year running, and younger and more diverse audiences visited our nine museums. Birmingham I present the 2016/17 Museum & Art Gallery was the 88th most visited art museum in the world. We won seven awards annual report for and attracted more school children to our venues Birmingham Museums than we have for five years. A Wellcome Trust funded outreach project enabled Trust. -

Download This PDF File

Leah Tether and Laura Chuhan Campbell Early Book Collections and Modern Audiences: Harnessing the Identity/ies of Book Collections as Collective Resources This article summarizes and contextualizes the discussions of a workshop held at Durham University in November 2018. In this workshop, participants (includ- ing academics, students, independent scholars, special and rare books librarians, and archivists) discussed the notion of the collection (that is, the identity of collection as a whole, rather than just its constituent parts), and its potential to serve as a means of engaging both scholarly and public audiences with early book cultures. This study sets out a series of considerations and questions that might be used when tackling such special collections engagement projects, including ones involving more modern collections than the case studies examined here. In November 2018, the Institute for Medieval and Early Modern Studies at Durham University kindly funded a workshop to investigate the ways in which contemporary audiences have been, are being, and can become engaged with medieval and early- modern book culture through the provision and distribution of key resources. These resources range from published books to digital artefacts and editions; from replica teaching kits—such as scriptorium suitcases—to physical archives and repositories.1 The aim of the workshop, which was led by one of this article’s two authors (Leah Tether), was to build a picture of best practice to inform the teaching and commu- 1. The authors are grateful to Durham’s Institute for Medieval and Early Modern Studies for fund- ing the workshop, and to the administrators of the Residential Research Library Fellowships (jointly organized by Ushaw College and Durham University) that enabled Leah Tether to spend time in Durham in November 2018. -

Zenobia Kozak Phd Thesis

=><9<@6;4 @52 =.?@! =>2?2>B6;4 @52 3A@A>2 , />6@6?5 A;6B2>?6@C 52>[email protected] 0<8820@6<;? .;1 612;@6@C 9.>72@6;4 DIQRFME 7R\EN . @LIUMU ?WFPMVVIH JRT VLI 1IKTII RJ =L1 EV VLI AQMXITUMV[ RJ ?V# .QHTIYU '%%* 3WOO PIVEHEVE JRT VLMU MVIP MU EXEMOEFOI MQ >IUIETGL-?V.QHTIYU,3WOO@IZV EV, LVVS,$$TIUIETGL"TISRUMVRT[#UV"EQHTIYU#EG#WN$ =OIEUI WUI VLMU MHIQVMJMIT VR GMVI RT OMQN VR VLMU MVIP, LVVS,$$LHO#LEQHOI#QIV$&%%'($)%+ @LMU MVIP MU STRVIGVIH F[ RTMKMQEO GRS[TMKLV @LMU MVIP MU OMGIQUIH WQHIT E 0TIEVMXI 0RPPRQU 8MGIQUI Promoting the past, preserving the future: British university heritage collections and identity marketing Zenobia Rae Kozak PhD, Museum and Gallery Studies 20, November 2007 Table of Contents List of Figures………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations…………………………………………………………………………………......3 List of Appendices………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Abstract……………………………………………………..………………………………………………………………………7 1. Introduction: the ‘crisis’ of university museums…………………………………………...8 1.1 UK reaction to the ‘crisis’…………………………………………………………………………………………………9 1.2 International reaction to the ‘crisis’…………………………………………………………………………………14 1.3 Universities, museums and collections in the UK………………………………………………………………17 1.3.1 20th-century literature review…………………………………………………………………………………19 1.4 The future of UK university museums and collections………………………………………………………24 1.4.1 Marketing university museums -

Designation Panel

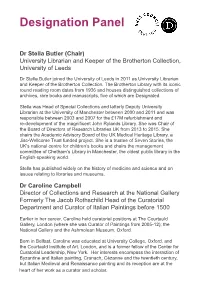

Designation Panel Dr Stella Butler (Chair) University Librarian and Keeper of the Brotherton Collection, University of Leeds Dr Stella Butler joined the University of Leeds in 2011 as University Librarian and Keeper of the Brotherton Collection. The Brotherton Library with its iconic round reading room dates from 1936 and houses distinguished collections of archives, rare books and manuscripts, five of which are Designated. Stella was Head of Special Collections and latterly Deputy University Librarian at the University of Manchester between 2000 and 2011 and was responsible between 2003 and 2007 for the £17M refurbishment and re-development of the magnificent John Rylands Library. She was Chair of the Board of Directors of Research Libraries UK from 2013 to 2015. She chairs the Academic Advisory Board of the UK Medical Heritage Library, a Jisc-Wellcome Trust funded project. She is a trustee of Seven Stories, the UK’s national centre for children’s books and chairs the management committee of Chetham’s Library in Manchester, the oldest public library in the English-speaking world. Stella has published widely on the history of medicine and science and on issues relating to libraries and museums. Dr Caroline Campbell Director of Collections and Research at the National Gallery Formerly The Jacob Rothschild Head of the Curatorial Department and Curator of Italian Paintings before 1500 Earlier in her career, Caroline held curatorial positions at The Courtauld Gallery, London (where she was Curator of Paintings from 2005-12); the National Gallery and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Born in Belfast, Caroline was educated at University College, Oxford, and the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, and is a former fellow of the Center for Curatorial Leadership, New York. -

News Update for London's Museums

@LondonMusDev E-update for London’s Museums – 10 June 2021 Museum Development London Recovery grants programme (£32k) supported by The Art Fund This programme, supported by The Art Fund, is designed to help museums to analyse and assess their current position and to identify priorities for activity to support post Covid recovery through a short, facilitated self-assessment process. Further to self-assessment and analysis 8 grants of up to £4000 will be available to successful participants. Further information and access to full guidance and application documents can be found here. Deadline for applications to the programme 05 July 2021. Museum Estate and Development Fund (MEND) The MEND grants scheme is an open-access capital fund targeted at non-national Accredited museums and local authorities based in England. Details of How to Apply are available on the ACE website. Closing date for applications: 05 July. As outlined in the ‘roadmap’ for England to move out of lockdown, museums are now able to open. The government has published the ‘COVID-19 Response - Spring 2021’ document, which outlines the plan in more detail. The move out of lockdown is reliant on four conditions which must be met before moving on a step – so these dates should be used as guides for the time being. Government has recently announced the Restart Grant scheme which supports businesses in the non-essential retail, hospitality, leisure, personal care and accommodation sectors with a one-off grant, to reopen safely as COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. The grants are available now through your local authorities and consist of either up to £6,000 in the non-essential retail sector (likely to reopen on 12th April) or up to £18,000 in the hospitality, museums, accommodation, leisure, personal care and gym sectors. -

Pearls and Wisdom

Pearls and wisdom Arts Council England’s vision for the Designation Scheme for collections of national significance 2 Contents Foreword 5 The development of the Scheme so far 7 Arts Council England’s vision for the future of Designation 10 Case studies Beamish, The Living Museum of the North 14 Library of Birmingham 16 Derby Museums Trust 18 Hull Museums 20 Norfolk Museums Services 22 Oxford University Museums 24 The Tank Museum 26 The Wellcome Library 28 The Wordsworth Trust 30 English Folk Dance and Song Society 32 Designated Collections by Area 34 3 Front cover: Astrolabe for Shah Abbas II, by Muhammad Muqim al-Yazdi, Persian, 1647/8. Credit: Museum of the History of Science, University of Oxford Inside cover: ‘The Co-op flag that covers the world’ Credit: National Co-operative Archive Below: Coronet worn by Princess Patricia to King Edward VII’s coronation in 1902 Credit: Historic Royal Palaces 4 Such collections, often shaped by Foreword strong characters and enduring enthusiasms, merge disciplines, crossing art and science in fascinating ways; they tell gripping stories, help us to understand our past, and suggest how our future might be different. These vital collections are located in rural and urban centres across the country, from Cornwall to Suffolk, from the South Coast to Cumbria. The Designation Scheme exists to recognise cultural collections of The Arts Council invests its funds and outstanding richness and resonance resources according to the objectives – collections that help deepen our set out in its 10-year strategy, Great art understanding of the world, and and culture for everyone. -

Midlands Innovation University Collections Group Project Report

Midlands Innovation: Supporting our Universities’ Collections Table of Contents Summary Sheet ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Methods ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Desk research ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Online survey .......................................................................................................................................... 3 One-to-one conversations ...................................................................................................................... 4 3. Characterising collections-based activity across the MI consortium ..................................................... 4 Collections content and status ................................................................................................................... 4 Programming for public and university audiences ..................................................................................... 7 Research Impact and Engagement ............................................................................................................ -

Government Indemnity Scheme Guidelines for Non-National Institutions

Government Indemnity Scheme Guidelines for non-national institutions Arts Council England January 2016 Non-national institutions are those institutions or bodies which are not wholly or mainly Exchequer-funded. They may be defined as those institutions or bodies falling within section 16 of the National Heritage Act 1980 set out in paragraph 2.1 of these guidelines. These non-national institutions and bodies include local authority-funded museums, galleries, libraries and other similar institutions and bodies; university museums and collections; National Trust properties; and local museums, galleries and other similar bodies which are governed by a charitable trust or society. Many of these bodies are listed in the Museums Yearbook (published by the Museums Association). If a non-national borrower wishes to check whether it is eligible under the Act it should contact the manager of the Government Indemnity Scheme at Arts Council England. Arts Council England 21 Bloomsbury Street London WC1 B3HF The Arts Council of England champions, develops and invests in artistic and cultural experiences that enrich people’s lives. It supports a range of activities across the arts, museums and libraries – from theatre to digital art, reading to dance, music to literature, and crafts to collections. Great art and culture inspires us, brings us together and teaches us about ourselves and the world around us. In short, it makes life better. The Arts Council is a Non-Departmental Public Body sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. -

News Update for London's Museums

@LondonMusDev E-update for London’s Museums – 27 May 2021 Museum Estate and Development Fund (MEND) The MEND grants scheme is an open-access capital fund targeted at non-national Accredited museums and local authorities based in England. Details of How to Apply are available on the ACE website. The scheme opens for expressions of interest from 01 June 2021. A webinar has been set up on 7th June for anyone considering an application, via Eventbrite. Closing date for applications: 05 July. As outlined in the ‘roadmap’ for England to move out of lockdown, museums are now able to open. The government has published the ‘COVID-19 Response - Spring 2021’ document, which outlines the plan in more detail. The move out of lockdown is reliant on four conditions which must be met before moving on a step – so these dates should be used as guides for the time being. Government has recently announced the Restart Grant scheme which supports businesses in the non-essential retail, hospitality, leisure, personal care and accommodation sectors with a one-off grant, to reopen safely as COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. The grants are available now through your local authorities and consist of either up to £6,000 in the non-essential retail sector (likely to reopen on 12th April) or up to £18,000 in the hospitality, museums, accommodation, leisure, personal care and gym sectors. You can find out more on the Gov.uk website and by contacting your local authority. The Government has updated regulations around the information that re- opened organisations must collect for Test and Trace. -

National Historic Shipsuk

REVIEW 2012 - 2013 CALENDAR 2014 National Historic Ships UK Foreword Last year we incorporated the annual review approach before. Given these positive into our calendar which enabled us to comments, I am pleased to say that we have circulate copies much more widely than in adopted this format for the foreseeable Martyn Heighton the past. We received many plaudits for this future, and I hope that this review and experiment, with respondents observing calendar gives as much pleasure and gets Director & Chair of Council that they had not seen such an imaginative to adorn even more walls than last year. National Historic Ships UK Front cover: Photo Competition Category A – Photo Competition Category B – Entry: Photo Competition Category C – Entry: Photo Competition Category B – Entry: Shortlisted Entry: I am going to get wet, Inspecting the port propeller, by Stephen Page. Deadeye, by Stephen Coley. Ship’s Telegraph System, Coronia, Scarborough, by Robert Skuse. by William Danby. 1. Introduction he Advisory Committee on National • To provide leadership, strategic vision across on secondment since April 2013 assisting in John Kearon: Historic Vessel Conservation Expert THistoric Ships (National Historic Ships) the UK historic ships’ communities and wider developing a project on the First World War David Newberry: Former Captain of HMS Warrior was set up in 2006 as an Advisory Non- maritime sectors by acting as the official voice for funded by HLF. David Ralph: Maritime & Coastguard Agency Departmental Public Body (NDPB) following historic vessels through proactive engagement John Robinson: Maritime Heritage Trust two reports from the House of Commons Select with the sector, the UK government, the Alan Watson: Medusa Trust Committee for Culture, Media and Sport on Devolved Administrations, public and private COUNCIL OF EXPERTS Stuart Wilkinson: Transport Trust the needs of historic vessels in the UK. -

Tim Knox News Release FINAL

News Release from the University of Cambridge Embargoed until 00.01 hrs Friday 7 December 2012 New Director appointed for the Fitzwilliam Museum The University of Cambridge has appointed a new Director to succeed Timothy Potts at the Fitzwilliam Museum. Tim Knox is currently Director of the Sir John Soane’s Museum in London where he has been since 2005. During his time there he masterminded the restoration of the two houses, Nos. 12 and 14 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which flank Soane’s original Museum at No. 13. The ambitious OUTS (Opening up the Soane) project, which has involved raising over £7 million, is now fully planned and financed, and ready to move into its second phase, the first having provided a new exhibition gallery, new conservation studios and a new museum shop. Tim Knox studied History of Art at the Courtauld Institute of Art. He was appointed Assistant Curator at the Royal Institute of British Architects Drawings Collection in 1989. In 1995 he moved to the National Trust as its Architectural Historian, becoming Head Curator in 2002. He was much involved with the restoration of the gardens at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, and championed the acquisition of the Workhouse in Southwell, Nottinghamshire, Tyntesfield in Somerset, and the restoration of the Darnley Mausoleum in Cobham Park, Kent. The Fitzwilliam Museum has enjoyed record breaking visitor numbers in recent years, with exhibitions including Vermeer’s Women and The Search for Immortality: Tomb Treasures of Han China drawing tens of thousands of extra visits to these and the permanent collections. The Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sir Leszek Borysiewicz, said: “Tim Knox has a tremendous reputation as a museum director, who has shown at the Soane Museum a sensitivity to the legacy of the founder coupled with a creative vision. -

The Museums, Libraries and Archives Council HC

MLA Pink Pantone© 240 The Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (a company limited by guarantee) Annual Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31 March 2010 HC 308 £14.75 Company Number 03888251 Registered Charity Number 1079666 The Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (a company limited by guarantee) Annual Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31 March 2010 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Article 6(2)(b) of The Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit-making Companies) Order 2009 - SI 2009 No. 476 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 26 July 2010 HC 308 LONDON: The Stationery Office Price: £14.75 The Museums, Libraries and Archives Council Grosvenor House 14 Bennetts Hill Birmingham B2 5RS The MLA is the government’s agency for developing and improving England’s museums, libraries and archives. We enable them to provide more and more people with high quality experiences that enrich their lives. Leading strategically, the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council promotes best practice in museums, libraries and archives, to inspire innovative, integrated and sustainable services for all. © Copyright MLA 2010 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as MLA 2010 copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. A CIP catalogue record of this publication is available from the British Library ISBN: 9780102968224 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID: 2378004 07/10 4800 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum The MLA is not responsible for views expressed by consultants or those cited from other sources.