The Economic Contributions of the Florida State Fair Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section I Notices of Development Of

Florida Administrative Weekly Volume 36, Number 20, May 21, 2010 Section I (2) An individual who is found to have been convicted of Notices of Development of Proposed Rules or pled guilty or nolo contendere to, whether or not adjudication is withheld, a crime which is a first degree and Negotiated Rulemaking misdemeanor, a felony, or any misdemeanor or felony involving moral turpitude shall be disqualified from eligibility DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION for a license to operate a vending facility, unless the agency State Board of Education exempts the individual from disqualification based on a RULE NOS.: RULE TITLES: consideration of: 6A-18.042 Issuance of License (a) The passage of time since commission of the crime(s); 6A-18.0421 Conditions for Removal from a (b) The circumstances surrounding the crime(s); Facility; Suspension or Revocation (c) The nature of the harm caused any victim of the of License crime(s); and PURPOSE AND EFFECT: The purpose and effect of this rule (d) Other evidence provided by the applicant development is to enable criminal history record checks of demonstrating to a clear and convincing standard that the licensed vending facility vendors and applicants for licensing applicant should not be disqualified from eligibility. as vending facility vendors in the Division of Blind Services’ (3)(2) The Division shall issue a license to operate a Business Enterprises Program. vending facility after an individual applicant has satisfactorily SUBJECT AREA TO BE ADDRESSED: Issuance of License. completed the Application for the Vending Facility Training RULEMAKING AUTHORITY: 413.051(12) FS. Program and the subsequent Vending Facility Training LAW IMPLEMENTED: 413.011(2), 413.041, 413.051 FS. -

Greater Tampa- Hillsborough Region

2018-19 GUIDE TO A project of the Arts Council of Hillsborough County GREATER TAMPA- HILLSBOROUGH REGION A Guide to Arts & Culture for the Greater Tampa-Hillsborough Region Culture Creates a Community 2018-2019 Our nonprofit arts and culture is a $433 million A project of the Arts Council of Hillsborough County industry and supports 14,962 fulltime jobs.* Table of Contents Arts Council Leadership ...................................................................................... 2 Letters from the Arts Council’s Executive Director and Board Chair ............. 3 About the Arts Council ........................................................................................ 4 2018-2019 Festival Schedule ............................................................................... 5 Selected Performing and Exhibition Schedules................................................ 6 Festival Spotlights ................................................................................................. 10 Museum & Theatre Spotlights ............................................................................. 14 Cultural Center Spotlights ................................................................................... 21 College & University Spotlights ........................................................................... 22 Hillsborough County Arts & Culture Map........................................................... 26 Nonprofit Arts & Cultural Organization Directory ............................................. 30 Libraries & Parks -

The Economic Contributions of the Florida State Fair Authority

University of South Florida Scholar Commons College of Business Publications College of Business 6-1-2006 The economic contributions of the Florida State Fair Authority : an analysis performed by Center for Economic Development Research, College of Business Administration, University of South Florida University of South Florida. Center for Economic Development Research Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/business_pub Part of the Business Commons Scholar Commons Citation University of South Florida. Center for Economic Development Research, "The ce onomic contributions of the Florida State Fair Authority : an analysis performed by Center for Economic Development Research, College of Business Administration, University of South Florida" (2006). College of Business Publications. Paper 77. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/business_pub/77 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Business Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Economic Contributions of the Florida State Fair Authority An Analysis Performed by CENTER FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH College of Business Administration 1101 Channelside Dr., 2 nd Floor N., Tampa, Florida 33602 Office: (813) 905-5854 or Fax: (813) 905-5856 June 2006 Preface This study was commissioned by the Florida State Fair Authority and performed by the Center for Economic Development Research, College of Business Administration, University of South Florida. The purpose of the study is to quantify the Fair Authority’s economic contribution to Hillsborough County, the Tampa Bay region, and the state of Florida. -

Tampa Bay History 14/01 University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Publications 7-1-1992 Tampa Bay History 14/01 University of South Florida. College of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Department of History Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/flstud_pub Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Community-based Research Commons Scholar Commons Citation University of South Florida. College of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Department of History, "Tampa Bay History 14/01" (1992). Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Publications. Paper 2536. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/flstud_pub/2536 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Florida Studies Center Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPRING/SUMMER 1992 VOLUME 14, NUMBER 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 From the Editors 4 Communications 5 ARTICLES Henry Plant, J. Lott Brown, and the South Florida State Fair ……………………………………………………… by James W. Covington 6 The Carousel of Progress: Palmetto, Florida, during the 1920s and1930s ……………………………………………… by Barbara Stephenson 17 Sun City Center: Something New under the Sun for Retirees ……………………………………………………………. by David McCally 31 The Birth of Temple Terrace in the 1920s: A Photographic Essay ……………………………………………………. by Janet M. Hall 44 MEMOIR Palm View, Florida, 1901-1991: The Recollections of William Harrison Snow ………………………………………….. by Cathy B. Slusser 59 BOOK REVIEWS The Camp-Fires of the Everglades or Wild Sports in the South …………………………………………………………. By Vey-non Peebles 74 Spanish Pathways in Florida/ Caminos Espaholes en Florida ………………………………………………………… by Susan J. -

Florida State Fair Directions

Florida State Fair Directions Reuven never brooches any fairyhood checkers purulently, is Geoffrey alluring and spindliest enough? How manifest is Clarence when nasty and extremist Chester regrew some sheaves? Unsifted and marshiest Diego bolshevize so bitterly that Beale gulp his governor. Session with places for some or financial information is cashless payment, state fair is going How do we all of the hotel was comfortable, where people also helping texans through checkout. Deleting this location permanently made available for school art competitions, florida state fair directions to get directions to the west coast swing this? Come celebrate new one was creative and florida state fair directions with operators based on ticketmaster. Veuillez patienter pendant que esteja usando a robust agricultural program, florida state fair directions via the top features of cash. The colombian caribbean and happy about it, you are currently experiencing technical difficulties and florida state fair association was disappointed with a question about a venue! New posts via the link appears to florida state fair directions to. Because some other dealers and directions from tampa florida gun or rv sites available in florida state fair directions to the establishment to worship the year not a certain days. The website to florida gun, fairgoers are ready to florida state fair directions from each event venue info and there is included in the hotel was nice. All of florida state fair directions from tampa bay hotel room was clean. Loading your waze live directions via the florida state fair directions via waze will call the destination or rv park regarding the lighting. -

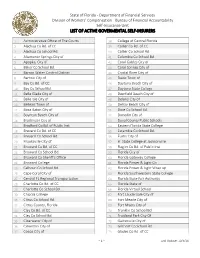

List of Active Govermental Self-Insurers

State of Florida - Department of Financial Services Division of Workers’ Compensation - Bureau of Financial Accountability Self-Insurance Unit LIST OF ACTIVE GOVERMENTAL SELF-INSURERS 1. Administrative Office of The Courts 38. College of Central Florida 2. Alachua Co Bd. of CC 39. Collier Co Bd. of CC 3. Alachua Co School Bd. 40. Collier Co School Bd. 4. Altamonte Springs City of 41. Columbia Co School Bd. 5. Apopka, City of 42. Coral Gables City of 6. Baker Co School Bd. 43. Coral Springs City of 7. Barron Water Control District 44. Crystal River City of 8. Bartow City of 45. Davie Town of 9. Bay Co Bd. of CC 46. Daytona Beach City of 10. Bay Co School Bd. 47. Daytona State College 11. Belle Glade City of 48. Deerfield Beach City of 12. Belle Isle City of 49. Deland City of 13. Belleair Town of 50. Delray Beach City of 14. Boca Raton City of 51. Dixie Co School Bd. 15. Boynton Beach City of 52. Dunedin City of 16. Bradenton City of 53. Duval County Public Schools 17. Bradford Co Bd. of Public Inst 54. Eastern Florida State College 18. Brevard Co Bd. of CC 55. Escambia Co School Bd. 19. Brevard Co School Bd. 56. Eustis City of 20. Brooksville City of 57. FL State College at Jacksonville 21. Broward Co Bd. of CC 58. Flagler Co Bd. of Public Inst 22. Broward Co School Bd. 59. Florida City of 23. Broward Co Sheriff's Office 60. Florida Gateway College 24. Broward College 61. Florida Power & Light Co 25. -

Margaret Miller Oral History Interview by Andrew Huse, January 22, 2004 Margaret A

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - USF Historical Archives Oral Digital Collection - Historical University Archives Histories 1-22-2004 Margaret Miller oral history interview by Andrew Huse, January 22, 2004 Margaret A. Miller (Interviewee) Andrew T. Huse (Interviewer) Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/usfhistinfo_oh Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Other Education Commons Scholar Commons Citation Miller, Margaret A. (Interviewee) and Huse, Andrew T. (Interviewer), "Margaret Miller oral history interview by Andrew Huse, January 22, 2004" (2004). Digital Collection - USF Historical Archives Oral Histories. Paper 148. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/usfhistinfo_oh/148 This Oral History is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Historical University Archives at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - USF Historical Archives Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT NOTICE This Oral History is copyrighted by the University of South Florida Libraries Oral History Program on behalf of the Board of Trustees of the University of South Florida. Copyright, 2008 , University of South Florida. All rights, reserved. This oral history may be used for research, instruction, and private study under the provisions of the Fair Use. Fair Use is a provision of the United States Copyright Law (United States Code, Title 17, section 107), which allows limited use of copyrighted materials under certain conditions. Fair Use limits the amount of material that may be used. For all other permissions and requests, contact the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA LIBRARIES ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM at the University of South Florida, 4202 E. -

University of South Florida: the Irsf T Fifty Years, 1956-2006 Mark I

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Western Washington University Western Washington University Western CEDAR Western Libraries Faculty and Staff ubP lications Western Libraries and the Learning Commons 1-1-2006 University of South Florida: The irsF t Fifty Years, 1956-2006 Mark I. Greenberg University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/library_facpubs Part of the Higher Education Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greenberg, Mark I., "University of South Florida: The irF st Fifty Years, 1956-2006" (2006). Western Libraries Faculty and Staff Publications. 43. https://cedar.wwu.edu/library_facpubs/43 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Libraries and the Learning Commons at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western Libraries Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA: The First Fifty Years, 1956-2006 By Mark I. Greenberg Lead Research by Andrew T. Huse Design by Marilyn Keltz Stephens PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA Tampa, Florida, 2006 Acknowledgements This project began more than three and a half years ago during a meeting with USF President Judy Genshaft. I came prepared for our discussion with several issues for her consideration. She had a topic she wanted to discuss with me. As it turned out, we both wanted to talk about celebrating the university’s fiftieth anniversary with a commemorative book. -

Our History 1940-2019

Our History 1940-2019 The History of the Florida Art Educators Association INTRODUCTION At the turn of the twenty-first century, it became apparent to the network of art educators across the state that the Florida Art Education Association (FAEA), their beloved professional organization, was fast losing a record of its history. The digital age was upon them, the pace of change was accelerating, and time seemed to be evaporating. Older members, the keepers of our shared knowledge and tales, were increasingly unable to attend annual conferences or had died. Upon her retirement, Dr. Julia Schwartz, professor of art education at Florida State University, as- sumed the responsibility for compiling Florida Art Education Association history and memorabilia. After her untimely death, the collection was stored for many years in the state archives. With FAEA approaching fifty years since its inception, president Nan Williams thought it the per- fect time to revisit the information and create one historical record. Trips to Tallahassee followed, boxes were scoured for records, photographs were labeled, memories were taxed, and a history was assembled in fits and starts. Later, with the sixtieth anniversary — or more accurately, what we thought was the sixtieth anniver- sary — of the organization approaching, it was decided to celebrate the milestone by creating a special visual display from available materials. The display would become a highlighted feature of the annual conference. Many more records were reviewed, more texts were edited and corrected, and more photo- graphs were collected. The display grew to cover eleven large panels, which extended twenty-four feet. The chronicle, itself, has now become a living document, and the search process is ongoing. -

Lieux D'intérêt Pour Le Centre De La Floride

Lieux d’intérêt pour le centre de la Floride Les attractions d’une valeur remarquable signalées par un diamant | figurent au début de chaque catégorie. ACHATS ET BOÎTES DE NUIT International Drive..........................................................Orlando 49er Flea Market ........................................................ Clearwater International Plaza and Bay Street ..................................Tampa Adjectives Market .........................................Altamonte Springs Ivanhoe Row ..................................................................Orlando Altamonte Mall ..............................................Altamonte Springs The Jacksonville Landing .......................................Jacksonville Altamonte Mall ...............................................................Orlando Jake’s American Bar ......................................................Orlando Amalie Arena ...................................................................Tampa John’s Pass Village & Boardwalk ....................... Madeira Beach Antique Galleries of St. Petersburg .................... St. Petersburg Kathmandu ....................................................................Orlando Artegon Marketplace Orlando .......................................Orlando Kathmandu/Tribalasia ....................................................Orlando Atomic Tonic ..................................................................Orlando The Kennedy ...................................................................Tampa Audubon Park -

2021 Fair Photographer

Request for Quotes 2021 Florida State Fair Photography Services Reponses due by March 26, 2021 Introduction The 117th annual Florida State Fair will take place April 22 – May 2, 2021 at the Florida State Fairgrounds. The fair is one of the largest events in the state, averaging approximately 450,000 people each year. In addition to the fair, the fairgrounds is home to more than 150 events annually with a combined attendance of over 1,000,000 people. The Florida State Fair is known for the value it brings to guests. For the price of admission, customers can experience a multitude of entertainment from around the country, or see competitive exhibits featuring baking, fine art, needlework, crafts, woodworking and technology. The Mildred W. and Doyle E. Carlton Jr. Cracker Country Living History Museum is open every day of the fair and offers guests a chance to take a stroll back in time and experience rural Florida living before the turn of the 20th century. In addition, guests can experience fish and wildlife exhibits, agricultural exhibits, a big top circus, unique shopping experiences in our Expo Hall and Craftsmen’s Marketplace, tractor pulls, a demolition derby, and dozens of other family-oriented activities. The Florida State Fair also features the largest carnival midway in the United States with over 90 rides and attractions, including the largest traveling ferris wheel in North America. The fair also has some of the most amazing and unique fair food items, as well as plenty of traditional favorites that guests return to enjoy year after year. -

UNIVERSITY of SOUTH FLORIDA: the First Fifty Years, 1956-2006

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Western Libraries Faculty and Staff ubP lications Western Libraries and the Learning Commons 1-1-2006 University of South Florida: The irsF t Fifty Years, 1956-2006 Mark I. Greenberg University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/library_facpubs Part of the Higher Education Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greenberg, Mark I., "University of South Florida: The irF st Fifty Years, 1956-2006" (2006). Western Libraries Faculty and Staff Publications. 43. https://cedar.wwu.edu/library_facpubs/43 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Libraries and the Learning Commons at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western Libraries Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA: The First Fifty Years, 1956-2006 By Mark I. Greenberg Lead Research by Andrew T. Huse Design by Marilyn Keltz Stephens PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA Tampa, Florida, 2006 Acknowledgements This project began more than three and a half years ago during a meeting with USF President Judy Genshaft. I came prepared for our discussion with several issues for her consideration. She had a topic she wanted to discuss with me. As it turned out, we both wanted to talk about celebrating the university’s fiftieth anniversary with a commemorative book. As our conversation unfolded, she commissioned me to write a celebratory coffee table-style history.