Do “Executive Courts” Pose a Problem in India’S Federal Democracy? : an Analysis Based on Shri Ranjan Gogoi’S Nomination to the Rajya Sabha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of India

Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Re: Filling up vacancies of Judges in the Supreme Court. Against the sanctioned strength of 31 Judges, the Supreme Court of India is presently functioning with 25 Judges, leaving six clear vacancies. The Collegium met today to consider filling up of these vacancies and after extensive discussion and deliberations unanimously resolves to fill up, for the present, two of these vacancies. The Collegium discussed names of Chief Justices and senior puisne High Court Judges eligible for appointment as Judges of the Supreme Court. The Collegium considers that at present Mr. Justice K.M. Joseph, who hails from Kerala High Court and is currently functioning as Chief Justice of Uttarakhand High Court, is more deserving and suitable in all respects than other Chief Justices and senior puisne Judges of High Courts for being appointed as Judges of the Supreme Court of India. While recommending the name of Mr. Justice K.M. Joseph, the Collegium has taken into consideration combined seniority on all-India basis of Chief Justices and senior puisne Judges of High Courts, apart from their merit and integrity. Mr. Justice K.M. Joseph was appointed as a Judge of the Kerala High Court on 14th October, 2004 and was elevated as Chief Justice of the Uttarakhand High Court on 31st July, 2014 and since Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) 2 then has been functioning there. He stands at Sl. No.45 in the combined seniority of High Court Judges on all-India basis. We have also considered the names of eminent members of the Bar. -

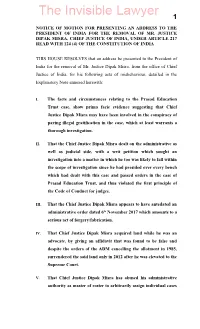

Notice of Motion for Presenting an Address to the President of India for the Removal of Mr

1 NOTICE OF MOTION FOR PRESENTING AN ADDRESS TO THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA FOR THE REMOVAL OF MR. JUSTICE DIPAK MISRA, CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA, UNDER ARTICLE 217 READ WITH 124 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA THIS HOUSE RESOLVES that an address be presented to the President of India for the removal of Mr. Justice Dipak Misra, from the office of Chief Justice of India, for his following acts of misbehaviour, detailed in the Explanatory Note annexed herewith: I. The facts and circumstances relating to the Prasad Education Trust case, show prima facie evidence suggesting that Chief Justice Dipak Misra may have been involved in the conspiracy of paying illegal gratification in the case, which at least warrants a thorough investigation. II. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra dealt on the administrative as well as judicial side, with a writ petition which sought an investigation into a matter in which he too was likely to fall within the scope of investigation since he had presided over every bench which had dealt with this case and passed orders in the case of Prasad Education Trust, and thus violated the first principle of the Code of Conduct for judges. III. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra appears to have antedated an administrative order dated 6th November 2017 which amounts to a serious act of forgery/fabrication. IV. That Chief Justice Dipak Misra acquired land while he was an advocate, by giving an affidavit that was found to be false and despite the orders of the ADM cancelling the allotment in 1985, surrendered the said land only in 2012 after he was elevated to the Supreme Court. -

Asia Index Launches S&P BSE Private Banks Index

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2018 Asia Index launches S&P BSE The International Women Entrepreneurs Sakshi Choudhary clinches Private Banks Index Summit 2018 gold medal at World Youth 5 September 2018 (International News) 5 September 2018 (International News) Boxing in Budapest The International Women Entrepreneurs 5 September 2018 ( Sports News) Asia Index Pvt Ltd, a joint Summit 2018 was inaugurated by the Vice venture between S&P Dow Jones President of Nepal Nanda Bahadur Pun in In boxing, Indices and BSE Ltd, announced Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal on former junior the launch of an index designed September 3, 2018. world champion to measure the performance of Nepal‘s Vice President emphasised upon empowering women boxer Sakshi private banks. in all areas including social, political and economic. The three- Choudhary day event is being organised by the South Asian Women added the youth The S&P BSE Private Banks Index is drawn from the Development Forum. It is expected to witness participation crown to her constituents of the S&P BSE Finance Index, the Asia's oldest from delegates belonging to 27 countries including China and cabinet in the 57- exchange said in a statement. the SAARC, ASEAN, EU, African and Arab countries. The kilogram Only common stocks classified as Banks by the BSE Sector Theme of the International Women Entrepreneurs Summit category, Classification model and that are not classified under the 2018: ‗Equality begins with Economic Empowerment‘ claiming the gold BSE scrip category as a Public Sector Undertaking (PSU) are Objective of the Summit at the World Youth Boxing in Budapest. -

To Download Petition

WWW.LIVELAW.IN 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO._________OF 2020 (A WRIT PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF CONSTITUTION OF INDIA) IN THE MATTER OF: POSITION OF PARTIES Madhu Purnima Kishwar D/o- Late Shri K L Kishwar VERSUS …..Petitioner 1. Union of India Contesting Through Home Secretary Respondent no. 1 North Block, Central Secretariat New Delhi. 2. Union of India Through Secretary Contesting Ministry of Law & Justice Respondent no. 2 Jaisalmer House New Delhi. 3. Supreme Court of India Through Secretary General Supreme Court of India. Contesting Tilak Marg, Respondent no. 3 New Delhi. A WRIT PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA FOR ISSUANCE OF WRIT IN WWW.LIVELAW.IN 2 NATURE OF MANDAMUS, APPROPRIATE ORDER OR DIRECTION, FOR APPLICATION OF SECTION 8 OF THE LOPKAL ACT ON JUDGES OF SUPREME COURT AND HIGH COURTS. To The Hon’ble Chief Justice of India And his companion Judges of the Supreme Court of India at New Delhi The humble Petition of the Petitioner above-named. MOST RESPECTFULLY SHOWETH: 1. That the petitioner is filing the present Writ petition under article 32 of the Constitution of India for issuance of writ in the nature of mandamus, appropriate order or direction, for application of restrictions contained in Section 8 of the Lopkal Act on judges of Supreme Court of India and various high courts. 1A. That the instant writ petition in the nature of Public Interest is being filed under Article 32 against the State and its functionaries for protecting the independence of WWW.LIVELAW.IN 3 judiciary which is part of the basic structure of the Constitution of India. -

Metoo in India: What's Next

Joshi | #MeToo in India: What's Next #MeToo in India: What's Next Shareen Joshi Last October, India was swept by the winds of the #MeToo movement. The first move came from the Indian film industry, when Tanushree Dutta, a prominent Indian actress, accused Nana Patekar, an established actor and filmmaker, of sexual harassment on the set of a movie in 2008. Days later, journalist Priya Ramani accused M.J. Akbar, a leading government minister, of sexual harassment. These moves opened the floodgates for many other women working in the Indian film industry, media, government, private sector, and academia. The movement had some immediate impacts. Nana Patekar was removed from his latest movie, M.J. Akbar resigned, and a wave of other resignations and boycotts followed. Since then, however, the winds have calmed. Many of the accused have marshalled legal, financial, and government resources to protect themselves. Nana Patekar, who had denied the charges, issued a legal notice to Tanushree Dutta to withdraw her allegations. Dutta has also been accused of placing a “curse” on others who she named as enablers of her alleged abuse. M.J. Akbar has accused Priya Ramani of defamation. Actor Alok Nath, who is on trial for the alleged rape of writer-producer Vinta Nanda, will star in a new movie entitled #MainBhi (a Hindi translation of #MeToo), in which he will play a judge who takes a strong stand against sexual harassment in Indian society.1 The arrival of the #MeToo moment was not a huge surprise. India is one of the most gender unequal societies in the world. -

Tnpsc Bits National

• • October – 21 TNPSC BITS ❖ Delhi Tourism in association with Government of Delhi, is organizing the second edition of ‘Shahpur Jat Autumn Festival’ which celebrating the city’s hub of fashion and striking history. o Shahpur Jat is of the oldest villages of the city and is home to potters, painters, designers, workshops, boutiques, historical tombs, cafes and many more. It is near the ruins of Alauddin Khilji’s medieval Siri Fort. ❖ Senior IPS officer of Gujarat cadre Anup Kumar Singh has been appointed as director general of the National Security Guard (NSG). o The NSG was raised as the federal contingency force to counter terrorists and hijack-like incidents in 1984. It’s 35th raising day was celebrated recently on October 15th at Manesar, Haryana. ❖ The Supreme Court has ordered the inter-cadre transfer of Assam National Register of Citizens (NRC) Coordinator Prateek Hajela IAS to Madhya Pradesh without specifying any reason. o For more on NRC please go here: https://www.tnpscthervupettagam.com/articles- detail/national-register-of-citizens-nrc ❖ Two Latin American countries – Brazil and Venezuela have won a contested election for a seat on the UN Human Rights Council. o The 193-member UN General Assembly elected 14 members to the 47- member Human Rights Council for three-year terms starting January 1, 2020. o Under its rules, seats are allocated to regions (Asian, African, Latin American.) to ensure geographical representation. ❖ At 6%, China’s GDP growth during July-September 2019 quarter has become the lowest-ever growth rate recorded in the last 30 years. o The U.S.-China trade war has worsened China’s jobs and wage situation and corporations also refrained from making capital investment. -

Judicial Independence and Impartiality: a Sinking Belief Naveed Naseem 1 Shaista Qayoom 2

INDIAN JOURNAL OF LAW AND JUSTICE Judicial Independence and Impartiality: A Sinking Belief Naveed Naseem 1 Shaista Qayoom 2 Abstract For efficient working of a republican setup rooted totally on Rule of law, an unbiased and impartial judiciary is indispensable. The percept of judicial independence and impartiality has brought greater significance in the countries with written constitutions, where the executive has been conferred with wide authority to sprint the government and the likelihood of abuse of such power is considerably high. In a country like India where judiciary is regarded as the watchdog of democracy, it undoubtedly becomes essential that judges in their individual capacities and the judiciary as a whole are unbiased and neutral of all interior and exterior influences in order to guard and shield the philosophical and conceptual phrases used in the preamble of the Indian Constitution. Besides, an impartial and independent choice mechanism is a sure safeguard for ensuring that persons with dubious integrity do not occupy high judicial offices, thereby enhancing public’s have faith and self assurance in justice delivery mechanism of the country. Considering the significance which an unelected judiciary wheels in our system, the screening of judges to man the superior courts cannot be confined to mere technical and professional competence and their approaches and philosophies have to be screened extensively. The paper attempts to reflect the significance adhered to the principle of independent and impartial judiciary and the urgency to defend and hold such standards earlier than its dimensions turn into just indistinct and academic concepts. The continuous government stalling in the appointment of judges to the Superior Courts, nominating judges to political offices and occasionally unscrupulous conduct by some judges in the recent past, where judiciary on most part seemed to side with the executive, has raised questions on independent and impartial identity of judiciary. -

Clcns at TOP GOVERNANCE

SOME OF OUR GLITTERING STARS… CLCns AT TOP GOVERNANCE Late. Shri Arun Jaitley Former Minister of Finance, Minister of Corporate Affairs and Minister of Information and Broadcasting in the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1974 - 1977) Mr. Kiren Rijiju Minister of State of the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports and Ministry of State in the Ministry of Minority Affairs Former Minister of State of Home Affairs on the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1990 - 1993) 1 Mr. Kapil Sibal Former Minister of Law and Justice, Minister of Communications and Information Technology of the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1968 - 1970) Mr. Bhupinder Singh Hooda Mr. Jarbom Gamlin Former Chief Minister of Haryana Former Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh Batch (1968 - 1971) Batch (1981 – 1984) 2 CLCns AT THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon'ble Mr. Justice M.M. Punchhi Hon'ble Mr. Justice Y.K. Sabharwal Former Chief Justice of India Former Chief Justice of India Batch (1952 - 55) Batch (1961 - 1964) Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ranjan Gogoi Former Chief Justice of India Batch (1975- 1978) 3 Hon'ble Mr. Justice Vikramajit Sen Hon'ble Mr. Justice Madan B. Lokur Former Supreme Court Judge Former Supreme Court Judge Batch (1974 - 1977) Batch (1974 - 1977) Hon'ble Mr. Justice Arjan Kumar Sikri Former Supreme Court Judge Batch (1971 - 1974) 4 SITTING JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon'ble Mr. Justice Rohinton F. Nariman Hon’ble Dr. Justice D. Y. Chandrachud Batch (1971 - 1974) Batch (1979 – 1982) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Navin Sinha Hon’ble Mr. Justice Deepak Gupta Batch (1976 – 1979) Batch (1975 – 1978) 5 Hon'ble Mr. -

![[2014] 4 SCR 583 ABCDEFGHABCDEFGH 584 583 RAM NIRANJAN ROY V. STATE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0949/2014-4-scr-583-abcdefghabcdefgh-584-583-ram-niranjan-roy-v-state-2170949.webp)

[2014] 4 SCR 583 ABCDEFGHABCDEFGH 584 583 RAM NIRANJAN ROY V. STATE

[2014] 4 S.C.R. 583 584 SUPREME COURT REPORTS [2014] 4 S.C.R. RAM NIRANJAN ROY A A Supreme Court - He is guilty of contempt of Supreme Court v. - He is directed to pay a fine of Rs. 25,000/- - Constitution of STATE OF BIHAR AND ORS. India, 1950 - Art. 129. (Criminal Appeal No. 1240 of 2004) CONTEMPT OF COURT: MARCH 31, 2014 B B Contempt in the face of court - Held: When a contempt [RANJANA PRAKASH DESAI AND is committed in the face of the High Court or the Supreme MADAN B. LOKUR, JJ.] Court to scandalize or humiliate the Judge, instant action may be necessary - There was no question of giving the appellant CONTEMPT OF COURTS ACT, 1971: any opportunity to make his defence - Natural justice - C C Opportunity of hearing. s. 14 - Contempt of court - Contemner appearing-in- person before High Court and shouting at court and making In a writ petition (C.W.J.C. No.1311 of 2003), filed in false statement before court - High Court holding him guilty public interest, raising several issues relating to law and of contempt of court and directing him to be taken into custody order problem in the State of Bihar, the High Court and to be sent to jail for 24 hours as punishment - Held: The D D directed the Director General of Police to make a list of intemperate language used by the appellant while addressing officers starting from the Station House Officers up to the the Judges of the High Court is most objectionable and Additional Director General of Police, of those who had contumacious - He did not show any remorse - He did not remained in their station for more than four years. -

List of Chief Justices of India There Have Been 47 Chief Justices in India Till Date

List of Chief Justices of India There have been 47 Chief justices in India till date. H J Kania served as the First Chief Justice Of Supreme Court of India. The list of Chief Justice of India is given below: Chief Justice of India – List Tenure H.J Kania 26 January 1950 – 6 November 1951 M. Patanjali Sastri 7 November 1951 – 3 January 1954 Mehr Chand Mahajan 4 January 1954 – 22 December 1954 Bijan Kumar Mukherjea 23 December 1954 – 31 January 1956 Sudhi Ranjan Das 1 February 1956 – 30 September 1959 Bhuvaneshwar Prasad Sinha 1 October 1959 – 31 January 1964 P. B. Gajendragadkar 1 February 1964 – 15 March 1966 Amal Kumar Sarkar 16 March 1966 – 29 June 1966 Koka Subba Rao 30 June 1966 – 11 April 1967 Kailas Nath Wanchoo 12 April 1967 – 24 February 1968 Mohammad Hidayatullah 25 February 1968 – 16 December 1970 Jayantilal Chhotalal Shah 17 December 1970 – 21 January 1971 Sarv Mittra Sikri 22 January 1971 – 25 April 1973 A. N. Ray 26 April 1973 – 27 January 1977 Mirza Hameedullah Beg 29 January 1977 – 21 February 1978 Y. V. Chandrachud 22 February 1978 – 11 July 1985 P. N. Bhagwati 12 July 1985 – 20 December 1986 Raghunandan Swarup Pathak 21 December 1986 – 18 June 1989 Engalaguppe Seetharamaiah Venkataramiah 19 June 1989 – 17 December 1989 Sabyasachi Mukharji 18 December 1989 – 25 September 1990 Ranganath Misra 26 September 1990 – 24 November 1991 Kamal Narain Singh 25 November 1991 – 12 December 1991 Madhukar Hiralal Kania 13 December 1991 – 17 November 1992 Lalit Mohan Sharma 18 November 1992 – 11 February 1993 M. -

Appendix by Avani Bansal.Pdf

AGE TENURE IN WHILE PREVIOUS LEGAL DIFFERENTLY NAME STATE RELIGION GENDER EDUCATION STATUS SC AS CJI MOVING POSITION LEGACY ABLED TO SC Associate Judge of the 26th January Federal Court 1950 – 6th LLB & LLM from (then was H.J. KANIA November Gujarat 60 yrs. Hindu Male None No Government Law appointed as 1951 (1 year, College, Bombay the first CJ in 284 days) Supreme Court) Third in 7 November seniority in 1951 - 3 B.A and LLB from M. Patanjali Madras High January 1954 Madras 62 yrs. Hindu Male None No Madras University in Sastri Court, later, (2 years, 1912 Judge of the 57 days) Federal Court 4 January Prime 1954 - 22 Father LL. B degree from Mehr Chand Himachal Minister of December 65 yrs. Hindu Male (Advocate No Government Mahajan Pradesh Jammu & 1954 Lala Brij Lal) College, Lahore Kashmir (352 days) 23 Judge in December M.A.(History), B.L. Supreme Bijan Kumar 1954 – 31 (Gold Medalist), Calcutta 63 yrs. Hindu Male Court 14 Oct. None No Mukherjea January 1956 M.L.(Gold Medalist), 1948-22 (1 year, Doctor of Law Dec.1954. 39 days) 1 February Chief Justice 1956 – 30 of Punjab September L.L.B from University Sudhi Ranjan Das Calcutta 62 yrs. Hindu Male High Court None No 1959 College, London from 1949 to (3 years, 1950. 241 days) 1 October B.A. (Hons.) and 1959 – 31 Chief Justice Bhuvaneshwar M.A. Examinations January 1964 Bihar 60 yrs. Hindu Male of Bombay None No Prasad Sinha of the Patna (4 years, High Court University 122 days) 1 February M.A. -

Jaypee Infratech Limited

31 August, 2019 Jaypee Infratech Limited List of Home buyers who have not submitted their claim Please note that these home buyers are not part of CoC as we have not received the claim forms within prescribed period. However, they continue to remain allottees as per the books of the corporate debtor. S.No Unit Number Status of Unit Name of Customer S.No Unit Number Status of Unit Name of Customer 1 AM0A101A02 Active Vidya Sagar Dixit 1328 KM00241502 Active Bharti Mishra 2 AM0A102A06 Active Jogindro Devi Sharma 1329 KM00241804 Active Grip Software Private 3 AM0A102B01 Active Rahul Verma 1330 KM00241902 Active Praveen Kumar Jain 4 AM0A102B06 Active Sonali Seth 1331 KM00250604 Active Sabah Imam 5 AM0A103A02 Active Mani Bhushan Kishor 1332 KM00250803 Active Dinesh Kumar Sethi 6 AM0A103A06 Active Lalit Kumar Srivastava 1333 KM00260201 Active Jamal Akhtar Aziz 7 AM0A103B02 Active Sunil Kataria 1334 KM00260203 Active Vimla Gupta 8 AM0A103B03 Active Gopal Singh 1335 KM00260403 Active Sakshi Roy 9 AM0A103B05 Active Jitender Singh 1336 KM00260404 Active Kanika Sharma 10 AM0A104A01 Active Faisal Ameen 1337 KM00260601 Active Vinay Bindal 11 AM0A104B02 Active Sunil Talwar 1338 KM00260703 Active Sampann Neb 12 AM0A104B04 Active Saurabh Pratap Singh 1339 KM00260903 Active Anurag Bhardwaj 13 AM0A105A04 Inactive Deepak Ranjan Gogoi 1340 KM00261804 Active Rajeshwar Dutt Sharma 14 AM0A105B06 Active Ashish Kumar 1341 KM00262003 Active Maheshwar Dutt Sharma 15 AM0A106A07 Active Nimesh Kumar 1342 KM00280102 OOP Kartar Chand Nandolia 16 AM0A106B04 Active Gopal Swaroop Bajpai 1343 KM00280703 OOP Tej Singh 17 AM0A107A05 Active Manoj Kumar Prasad 1344 KM00281205 OOP Shashi Khandelwal 18 AM0A108A05 Active Ashok Kumar Arora 1345 KM00281701 OOP Sundeep Kaura Huf 19 AM0A108B01 Active Satyendra Mishra 1346 KM00290105 OOP Vikas Agarwal 20 AM0A109A02 Active Ashutosh Sharma 1347 KM00290502 OOP T.R.