Metoo in India: What's Next

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of India

Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Re: Filling up vacancies of Judges in the Supreme Court. Against the sanctioned strength of 31 Judges, the Supreme Court of India is presently functioning with 25 Judges, leaving six clear vacancies. The Collegium met today to consider filling up of these vacancies and after extensive discussion and deliberations unanimously resolves to fill up, for the present, two of these vacancies. The Collegium discussed names of Chief Justices and senior puisne High Court Judges eligible for appointment as Judges of the Supreme Court. The Collegium considers that at present Mr. Justice K.M. Joseph, who hails from Kerala High Court and is currently functioning as Chief Justice of Uttarakhand High Court, is more deserving and suitable in all respects than other Chief Justices and senior puisne Judges of High Courts for being appointed as Judges of the Supreme Court of India. While recommending the name of Mr. Justice K.M. Joseph, the Collegium has taken into consideration combined seniority on all-India basis of Chief Justices and senior puisne Judges of High Courts, apart from their merit and integrity. Mr. Justice K.M. Joseph was appointed as a Judge of the Kerala High Court on 14th October, 2004 and was elevated as Chief Justice of the Uttarakhand High Court on 31st July, 2014 and since Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) 2 then has been functioning there. He stands at Sl. No.45 in the combined seniority of High Court Judges on all-India basis. We have also considered the names of eminent members of the Bar. -

35°C—47°C Today D

Community Community Bazm-e-Sadaf Chaliyar Doha International’s observes P7evening for Urdu P16 World lovers is attended Environment Day by Doha-based in association writers and with embassy of poets. India. Sunday, June 10, 2018 Ramadan 25, 1439 AH DOHA 35°C—47°C TODAY PUZZLES 12 & 13 LIFESTYLE/HOROSCOPE 14 Incredible journey Bollywood yesteryear star COVER Kajol on her journey and STORY the latest ventures. P4-5 2 GULF TIMES Sunday, June 10, 2018 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.14am Shorooq (sunrise) 4.43am Zuhr (noon) 11.33am Asr (afternoon) 2.56pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.27pm Isha (night) 7.57pm USEFUL NUMBERS Kaala lead role, while Nana Patekar, Samuthirakani, Easwari Rao DIRECTION: Pa. Ranjith portray the supporting roles. Music is composed by Santhosh CAST: Rajinikanth, Huma Qureshi, Nana Patekar Narayanan. Kaala who runs away from Tirunelveli in his SYNOPSIS: Kaala is an upcoming Indian Tamil political childhood, moves to Mumbai where he becomes a powerful gangster movie written and directed by Pa Ranjith and don living in the slums of Dharavi. produced by Dhanush. The fi lm stars Rajinikanth in the THEATRES: The Mall, Royal Plaza, Landmark Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 Qatar General Electricity and Water Corporation 44845555, 44845464 Primary Health Care Corporation 44593333 44593363 Qatar Assistive Technology Centre 44594050 Qatar News Agency 44450205 44450333 Q-Post – General Postal Corporation 44464444 Humanitarian Services Offi ce (Single window facility for the repatriation of bodies) Ministry of Interior 40253371, 40253372, 40253369 Ministry of Health 40253370, 40253364 Hamad Medical Corporation 40253368, 40253365 Qatar Airways 40253374 Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom destruction of the Jurassic World theme soon encounter terrifying new breeds DIRECTION: J. -

Irish Musician Philip Noone on Qatar's World Class Recording Studios, His

YOUR PAGE, YOUR STAGE! There’s probably a photographer hidden in each of us, looking out for a platform. Community invites you to grab your chance and send your contributions with contact details and complete description of the images to [email protected] — PHOTO ESSAY, Page 10 Thursday, June 20, 2019 Shawwal 17, 1440 AH Doha today: 330 - 420 AA soundsound pitchpitch Irish musician Philip Noone on Qatar’s world class recording studios, his hit Doha releases and breaking fresh ground for the country. P4-5 COVER STORY REVIEWS BACK PAGE A weightless, unmemorable, Learning authentic Italian globe-trotting mediocrity. cuisine in style. Page 14 Page 16 2 GULF TIMES Thursday, June 20, 2019 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.13am Shorooq (sunrise) 4.45am Zuhr (noon) 11.37am Asr (afternoon) 3pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.28pm Isha (night) 7.58pm Unda in North India for election duty. During a volatile election USEFUL NUMBERS DIRECTION: Khalid Rahman season, a group of policemen led by Sub Inspector Mani strive CAST: Mammootty, Asif Ali, Vinay Forrt to maintain law and order in a Naxalite stronghold. SYNOPSIS: The fi lm narrates the events that occur when a unit of policemen from Kerala reach the Naxalite prone areas THEATRES: The Mall, Landmark, Royal Plaza Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, -

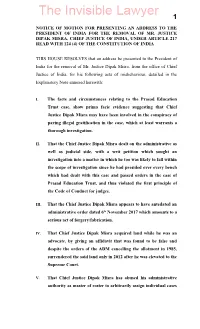

Notice of Motion for Presenting an Address to the President of India for the Removal of Mr

1 NOTICE OF MOTION FOR PRESENTING AN ADDRESS TO THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA FOR THE REMOVAL OF MR. JUSTICE DIPAK MISRA, CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA, UNDER ARTICLE 217 READ WITH 124 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA THIS HOUSE RESOLVES that an address be presented to the President of India for the removal of Mr. Justice Dipak Misra, from the office of Chief Justice of India, for his following acts of misbehaviour, detailed in the Explanatory Note annexed herewith: I. The facts and circumstances relating to the Prasad Education Trust case, show prima facie evidence suggesting that Chief Justice Dipak Misra may have been involved in the conspiracy of paying illegal gratification in the case, which at least warrants a thorough investigation. II. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra dealt on the administrative as well as judicial side, with a writ petition which sought an investigation into a matter in which he too was likely to fall within the scope of investigation since he had presided over every bench which had dealt with this case and passed orders in the case of Prasad Education Trust, and thus violated the first principle of the Code of Conduct for judges. III. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra appears to have antedated an administrative order dated 6th November 2017 which amounts to a serious act of forgery/fabrication. IV. That Chief Justice Dipak Misra acquired land while he was an advocate, by giving an affidavit that was found to be false and despite the orders of the ADM cancelling the allotment in 1985, surrendered the said land only in 2012 after he was elevated to the Supreme Court. -

Asia Index Launches S&P BSE Private Banks Index

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2018 Asia Index launches S&P BSE The International Women Entrepreneurs Sakshi Choudhary clinches Private Banks Index Summit 2018 gold medal at World Youth 5 September 2018 (International News) 5 September 2018 (International News) Boxing in Budapest The International Women Entrepreneurs 5 September 2018 ( Sports News) Asia Index Pvt Ltd, a joint Summit 2018 was inaugurated by the Vice venture between S&P Dow Jones President of Nepal Nanda Bahadur Pun in In boxing, Indices and BSE Ltd, announced Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal on former junior the launch of an index designed September 3, 2018. world champion to measure the performance of Nepal‘s Vice President emphasised upon empowering women boxer Sakshi private banks. in all areas including social, political and economic. The three- Choudhary day event is being organised by the South Asian Women added the youth The S&P BSE Private Banks Index is drawn from the Development Forum. It is expected to witness participation crown to her constituents of the S&P BSE Finance Index, the Asia's oldest from delegates belonging to 27 countries including China and cabinet in the 57- exchange said in a statement. the SAARC, ASEAN, EU, African and Arab countries. The kilogram Only common stocks classified as Banks by the BSE Sector Theme of the International Women Entrepreneurs Summit category, Classification model and that are not classified under the 2018: ‗Equality begins with Economic Empowerment‘ claiming the gold BSE scrip category as a Public Sector Undertaking (PSU) are Objective of the Summit at the World Youth Boxing in Budapest. -

True Or Pure” Republic the Window Is Still Open for Registration for the Eligible Educators Upto What Does It Mean to Be a 30Th November 2017

ISSN 2347-162X Happy Uttarayan RNI No. GUJENG/2002/23382 | Postal Registration No. GAMC-1732 | 2016-18 Issued by SSP Ahd-9, Posted at P.S.O. 10th Every Month Ahmedabad-2, Valid up to 31-12-2018 AHMEDABAD, FRIDAY, JANUARY 5, 2018 VOL.16, ISSUE-9 www.theopenpage.co.in facebook.com/theopenpage (12 + 4) TOTAL PAGE -16 INVITATION PRICE: `30/- From, The Open Page, 4th Floor Vishwa Arcade, Opp. Kum-Kum Party Plot, Nr. Akhbarnagar, Nava Wadaj, Ahmedabad - 380013 | Ph : 079-27621385/86 4th EDUCATOR’S AWARD We are honoured to NEED OF EVERY NATION – tO FORM announce the program date of the 4th Educator’s award 11th January 2018 at VADODARA “trUE OR PURE” REPUBLIC The window is still open for registration for the eligible educators upto WHAT DOes IT MEAN TO BE A 30th November 2017. REPUBLIC? "The roots of education are bitter, but Of course the Republic is a government fruits are sweet!" formed by people elected by the popula- tion in the democratic way. The constitu- tion of India is the supreme law of India. We find frame work defining fundamen- tal political principle, establishes the structure, procedure, power and duties of government institutions and sets out fundamental right, directive principle and duty of citizens. India implemented its own plan on Janu- ary 26, 1950, since then every year January 26 is celebrated as a Republic Day. What really means to be republic? What is to be done in the Republic Day celebration ? When any nation is released from oth- er foreign nationals, it becomes an inde- clarity for 2 years, 11 months and 17 days is a gift to the people of India's pendent public. -

Welcome Movie Anil Kapoor Entry Music Download

Welcome movie anil kapoor entry music download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD · Akshay Kumar, Katrina Kaif, Anil Kapoor, Feroz Khan, Paresh Rawal, Nana Patekar, Mallika Sherawat Check After Some To Get Welcome High Quality Mobile Ringtones. Welcome Movie Tag Cloud. Welcome, Welcome ringtones, Welcome mp3 ringtones, Welcome polyphonic ringtones, Welcome wav ringtones, Welcome mobile ringtones, Welcome cellphone renuzap.podarokideal.ru?movie=welcome. 1 day ago · ‘No Entry’ turns Anil Kapoor recalls his ‘be positive’ moments,Mumbai, Aug 26 (IANS) The multistarrer comedy blockbuster No Entry was released 15 years ago on this day and Anil Kapoor, one of its stars, celebrated by recalling the famous dialogue renuzap.podarokideal.ru 1 day ago · The multistarrer comedy blockbuster No Entry was released 15 years ago on this day and Anil Kapoor, one of its stars, celebrated by recalling the famous dialoguerenuzap.podarokideal.ru · No Entry. No Entry is a comedy movie directed by Anees Bazmee. Featuring an ensemble cast, the movie was bankrolled by Boney Kapoor. The cast of the movie includes Salman Khan, Anil Kapoor, Lara Dutta, Fardeen Khan, Bipasha Basu and more. No Entry is the official remake of the Tamil movie Charlie Chaplin. The plot of the movie features how renuzap.podarokideal.ru Anil Kapoor is mighty impressed by his daughter Sonam and Hrithik Roshan’s music video “Dheere Dheere”, a new version of the popular track from block-buster “Aashiqui”. The song is said to be a tribute to late T-series founder Gulshan renuzap.podarokideal.ru://renuzap.podarokideal.ru /sonam-hrithiks-music-video-is-fantastic-anil-kapoor. · Released in , Dil Tera Aashiq is a romantic-comedy movie helmed by Lawrence D’Souza. -

To Download Petition

WWW.LIVELAW.IN 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO._________OF 2020 (A WRIT PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF CONSTITUTION OF INDIA) IN THE MATTER OF: POSITION OF PARTIES Madhu Purnima Kishwar D/o- Late Shri K L Kishwar VERSUS …..Petitioner 1. Union of India Contesting Through Home Secretary Respondent no. 1 North Block, Central Secretariat New Delhi. 2. Union of India Through Secretary Contesting Ministry of Law & Justice Respondent no. 2 Jaisalmer House New Delhi. 3. Supreme Court of India Through Secretary General Supreme Court of India. Contesting Tilak Marg, Respondent no. 3 New Delhi. A WRIT PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA FOR ISSUANCE OF WRIT IN WWW.LIVELAW.IN 2 NATURE OF MANDAMUS, APPROPRIATE ORDER OR DIRECTION, FOR APPLICATION OF SECTION 8 OF THE LOPKAL ACT ON JUDGES OF SUPREME COURT AND HIGH COURTS. To The Hon’ble Chief Justice of India And his companion Judges of the Supreme Court of India at New Delhi The humble Petition of the Petitioner above-named. MOST RESPECTFULLY SHOWETH: 1. That the petitioner is filing the present Writ petition under article 32 of the Constitution of India for issuance of writ in the nature of mandamus, appropriate order or direction, for application of restrictions contained in Section 8 of the Lopkal Act on judges of Supreme Court of India and various high courts. 1A. That the instant writ petition in the nature of Public Interest is being filed under Article 32 against the State and its functionaries for protecting the independence of WWW.LIVELAW.IN 3 judiciary which is part of the basic structure of the Constitution of India. -

Tnpsc Bits National

• • October – 21 TNPSC BITS ❖ Delhi Tourism in association with Government of Delhi, is organizing the second edition of ‘Shahpur Jat Autumn Festival’ which celebrating the city’s hub of fashion and striking history. o Shahpur Jat is of the oldest villages of the city and is home to potters, painters, designers, workshops, boutiques, historical tombs, cafes and many more. It is near the ruins of Alauddin Khilji’s medieval Siri Fort. ❖ Senior IPS officer of Gujarat cadre Anup Kumar Singh has been appointed as director general of the National Security Guard (NSG). o The NSG was raised as the federal contingency force to counter terrorists and hijack-like incidents in 1984. It’s 35th raising day was celebrated recently on October 15th at Manesar, Haryana. ❖ The Supreme Court has ordered the inter-cadre transfer of Assam National Register of Citizens (NRC) Coordinator Prateek Hajela IAS to Madhya Pradesh without specifying any reason. o For more on NRC please go here: https://www.tnpscthervupettagam.com/articles- detail/national-register-of-citizens-nrc ❖ Two Latin American countries – Brazil and Venezuela have won a contested election for a seat on the UN Human Rights Council. o The 193-member UN General Assembly elected 14 members to the 47- member Human Rights Council for three-year terms starting January 1, 2020. o Under its rules, seats are allocated to regions (Asian, African, Latin American.) to ensure geographical representation. ❖ At 6%, China’s GDP growth during July-September 2019 quarter has become the lowest-ever growth rate recorded in the last 30 years. o The U.S.-China trade war has worsened China’s jobs and wage situation and corporations also refrained from making capital investment. -

Judicial Independence and Impartiality: a Sinking Belief Naveed Naseem 1 Shaista Qayoom 2

INDIAN JOURNAL OF LAW AND JUSTICE Judicial Independence and Impartiality: A Sinking Belief Naveed Naseem 1 Shaista Qayoom 2 Abstract For efficient working of a republican setup rooted totally on Rule of law, an unbiased and impartial judiciary is indispensable. The percept of judicial independence and impartiality has brought greater significance in the countries with written constitutions, where the executive has been conferred with wide authority to sprint the government and the likelihood of abuse of such power is considerably high. In a country like India where judiciary is regarded as the watchdog of democracy, it undoubtedly becomes essential that judges in their individual capacities and the judiciary as a whole are unbiased and neutral of all interior and exterior influences in order to guard and shield the philosophical and conceptual phrases used in the preamble of the Indian Constitution. Besides, an impartial and independent choice mechanism is a sure safeguard for ensuring that persons with dubious integrity do not occupy high judicial offices, thereby enhancing public’s have faith and self assurance in justice delivery mechanism of the country. Considering the significance which an unelected judiciary wheels in our system, the screening of judges to man the superior courts cannot be confined to mere technical and professional competence and their approaches and philosophies have to be screened extensively. The paper attempts to reflect the significance adhered to the principle of independent and impartial judiciary and the urgency to defend and hold such standards earlier than its dimensions turn into just indistinct and academic concepts. The continuous government stalling in the appointment of judges to the Superior Courts, nominating judges to political offices and occasionally unscrupulous conduct by some judges in the recent past, where judiciary on most part seemed to side with the executive, has raised questions on independent and impartial identity of judiciary. -

Clcns at TOP GOVERNANCE

SOME OF OUR GLITTERING STARS… CLCns AT TOP GOVERNANCE Late. Shri Arun Jaitley Former Minister of Finance, Minister of Corporate Affairs and Minister of Information and Broadcasting in the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1974 - 1977) Mr. Kiren Rijiju Minister of State of the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports and Ministry of State in the Ministry of Minority Affairs Former Minister of State of Home Affairs on the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1990 - 1993) 1 Mr. Kapil Sibal Former Minister of Law and Justice, Minister of Communications and Information Technology of the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1968 - 1970) Mr. Bhupinder Singh Hooda Mr. Jarbom Gamlin Former Chief Minister of Haryana Former Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh Batch (1968 - 1971) Batch (1981 – 1984) 2 CLCns AT THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon'ble Mr. Justice M.M. Punchhi Hon'ble Mr. Justice Y.K. Sabharwal Former Chief Justice of India Former Chief Justice of India Batch (1952 - 55) Batch (1961 - 1964) Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ranjan Gogoi Former Chief Justice of India Batch (1975- 1978) 3 Hon'ble Mr. Justice Vikramajit Sen Hon'ble Mr. Justice Madan B. Lokur Former Supreme Court Judge Former Supreme Court Judge Batch (1974 - 1977) Batch (1974 - 1977) Hon'ble Mr. Justice Arjan Kumar Sikri Former Supreme Court Judge Batch (1971 - 1974) 4 SITTING JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon'ble Mr. Justice Rohinton F. Nariman Hon’ble Dr. Justice D. Y. Chandrachud Batch (1971 - 1974) Batch (1979 – 1982) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Navin Sinha Hon’ble Mr. Justice Deepak Gupta Batch (1976 – 1979) Batch (1975 – 1978) 5 Hon'ble Mr. -

29112003 Dt Mpr 01 D L C

DLD‹‰†‰KDLD‹‰†‰DLD‹‰†‰MDLD‹‰†‰C Pet project: A Weight and watch: THE TIMES OF INDIA piglet steals Kareena tips the Saturday, Theron’s heart scales in her favour Dog saves baby girl with kiss of life November 29, 2003 Man’s most faithful friend and Mick McDonald, stop- Page 8 Page 10 has done it again. A Golden ped their car and flagged Retriever has saved the life down a nearby ambulance. of a baby girl who had sto- Says Marion, ‘‘There is no pped breathing. Max blew doubt Max has saved our air into his owner’s little girl’s life. He two-year-old daug- is a hero. Shona hter Shona’s mou- might not have be- th when she start- en here today if it ed convulsing. was not for Max.’’ Shona’s parents, That’s the ‘max’ Marion Derrane for a compliment! OF INDIA MANOJ KESHARWANI POLL GIMMICKS GET NOBODY’S VOTE ARUN KUMAR DAS nil Dutt and Rajesh Romesh Sabharwal, an of the development wheeled in Times News Network Khanna. Taking a differ- independent candidate over the past five years. ‘‘This ent route was Kamla Na- in Gole Market, lit up train is a symbol of modern so- agicians, toy planes, gar BJP candidate Sur- the roads with candles ciety and depicts the progress coins, flowers, sweets, ya Prakash, who roped —his election symbol. the Congress has brought in,’’ MAmitabh Bachchan in Amitabh Bachchan Amidst all these gim- says CM Sheila Dikshit. and Sachin Tendulkar lookal- and Sachin Tendulkar micks, an independent The BJP, in turn, had four ikes, street plays, donkeys, par- lookalikes.