Zoonotic Poxviruses Associated with Companion Animals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Munich Outbreak of Cutaneous Cowpox Infection: Transmission by Infected Pet Rats

Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 126–131 INVESTIGATIVE REPORT The Munich Outbreak of Cutaneous Cowpox Infection: Transmission by Infected Pet Rats Sandra VOGEL1, Miklós SÁRDY1, Katharina GLOS2, Hans Christian KOrting1, Thomas RUZICKA1 and Andreas WOLLENBERG1 1Department of Dermatology and Allergology, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, and 2Department of Dermatology, Haas and Link Animal Clinic, Germering, Germany Cowpox virus infection of humans is an uncommon, another type of orthopoxvirus, from infected pet prairie potentially fatal, skin disease. It is largely confined to dogs have recently been described in the USA, making Europe, but is not found in Eire, or in the USA, Austral the medical community aware of the risk of transmission asia, or the Middle or Far East. Patients having contact of pox viruses from pets (3). with infected cows, cats, or small rodents sporadically Seven of 8 exposed patients living in the Munich contract the disease from these animals. We report here area contracted cowpox virus infection from an unusual clinical aspects of 8 patients from the Munich area who source: rats infected with cowpox virus bought from had purchased infected pet rats from a local supplier. Pet local pet shops and reputedly from the same supplier rats are a novel potential source of local outbreaks. The caused a clinically distinctive pattern of infection, which morphologically distinctive skin lesions are mostly res was mostly restricted to the patients’ neck and trunk. tricted to the patients’ necks, reflecting the infected ani We report here dermatologically relevant aspects of mals’ contact pattern. Individual lesions vaguely resem our patients in order to alert the medical community to ble orf or Milker’s nodule, but show marked surrounding the possible risk of a zoonotic orthopoxvirus outbreak erythema, firm induration and local adenopathy. -

Zoonotic Diseases of Public Health Importance

ZOONOTIC DISEASES OF PUBLIC HEALTH IMPORTANCE ZOONOSIS DIVISION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF COMMUNICABLE DISEASES (DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF HEALTH SERVICES) 22 – SHAM NATH MARG, DELHI – 110 054 2005 List of contributors: Dr. Shiv Lal, Addl. DG & Director Dr. Veena Mittal, Joint Director & HOD, Zoonosis Division Dr. Dipesh Bhattacharya, Joint Director, Zoonosis Division Dr. U.V.S. Rana, Joint Director, Zoonosis Division Dr. Mala Chhabra, Deputy Director, Zoonosis Division FOREWORD Several zoonotic diseases are major public health problems not only in India but also in different parts of the world. Some of them have been plaguing mankind from time immemorial and some have emerged as major problems in recent times. Diseases like plague, Japanese encephalitis, leishmaniasis, rabies, leptospirosis and dengue fever etc. have been major public health concerns in India and are considered important because of large human morbidity and mortality from these diseases. During 1994 India had an outbreak of plague in man in Surat (Gujarat) and Beed (Maharashtra) after a lapse of around 3 decades. Again after 8 years in 2002, an outbreak of pneumonic plague occurred in Himachal Pradesh followed by outbreak of bubonic plague in 2004 in Uttaranchal. Japanese encephalitis has emerged as a major problem in several states and every year several outbreaks of Japanese encephalitis are reported from different parts of the country. Resurgence of Kala-azar in mid seventies in Bihar, West Bengal and Jharkhand still continues to be a major public health concern. Efforts are being made to initiate kala-azar elimination programme by the year 2010. Rabies continues to be an important killer in the country. -

Guide for Common Viral Diseases of Animals in Louisiana

Sampling and Testing Guide for Common Viral Diseases of Animals in Louisiana Please click on the species of interest: Cattle Deer and Small Ruminants The Louisiana Animal Swine Disease Diagnostic Horses Laboratory Dogs A service unit of the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine Adapted from Murphy, F.A., et al, Veterinary Virology, 3rd ed. Cats Academic Press, 1999. Compiled by Rob Poston Multi-species: Rabiesvirus DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 1 Cattle Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 2 Deer and Small Ruminants Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral disease Respiratory viral disease Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 3 Swine Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 4 Horses Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Neurological viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Abortifacient/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 5 Dogs Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. -

The Clinical Features of Smallpox

CHAPTER 1 THE CLINICAL FEATURES OF SMALLPOX Contents Page Introduction 2 Varieties of smallpox 3 The classification of clinical types of variola major 4 Ordinary-type smallpox 5 The incubation period 5 Symptoms of the pre-eruptive stage 5 The eruptive stage 19 Clinical course 22 Grades of severity 22 Modified-type smallpox 22 Variola sine eruptione 27 Subclinical infection with variola major virus 30 Evidence from viral isolations 30 Evidence from serological studies 30 Flat-type smallpox 31 The rash 31 Clinical course 32 Haemorrhagic-type smallpox 32 General features 32 Early haemorrhagic-type smallpox 37 Late haemorrhagic-type smallpox 38 Variola minor 38 Clinical course 38 Variola sine eruptione and subclinical infection 40 Smallpox acquired by unusual routes of infection 40 Inoculation variola and variolation 40 Congenital smallpox 42 Effects of vaccination on the clinical course of smallpox 42 Effects of vaccination on toxaemia 43 Effects of vaccination on the number of lesions 43 Effects of vaccination on the character and evolution of the rash 43 Effects of vaccination in variola minor 44 Laboratory findings 44 Virological observations 44 Serological observations 45 Haematological observations 46 1 2 SMALLPOX AND ITS ERADICATION Page Complications 47 The skin 47 Ocular system 47 Joints and bones 47 Respiratory system 48 Gastrointestinal system 48 Genitourinary system 49 Central nervous system 49 Sequelae 49 Pockmarks 49 Blindness 50 Limb deformities 50 Prognosis of variola major 50 Calculation of case-fatality rates 50 Effects -

Comparative Analysis, Distribution, and Characterization of Microsatellites in Orf Virus Genome

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Comparative analysis, distribution, and characterization of microsatellites in Orf virus genome Basanta Pravas Sahu1, Prativa Majee 1, Ravi Raj Singh1, Anjan Sahoo2 & Debasis Nayak 1* Genome-wide in-silico identifcation of microsatellites or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in the Orf virus (ORFV), the causative agent of contagious ecthyma has been carried out to investigate the type, distribution and its potential role in the genome evolution. We have investigated eleven ORFV strains, which resulted in the presence of 1,036–1,181 microsatellites per strain. The further screening revealed the presence of 83–107 compound SSRs (cSSRs) per genome. Our analysis indicates the dinucleotide (76.9%) repeats to be the most abundant, followed by trinucleotide (17.7%), mononucleotide (4.9%), tetranucleotide (0.4%) and hexanucleotide (0.2%) repeats. The Relative Abundance (RA) and Relative Density (RD) of these SSRs varied between 7.6–8.4 and 53.0–59.5 bp/ kb, respectively. While in the case of cSSRs, the RA and RD ranged from 0.6–0.8 and 12.1–17.0 bp/kb, respectively. Regression analysis of all parameters like the incident of SSRs, RA, and RD signifcantly correlated with the GC content. But in a case of genome size, except incident SSRs, all other parameters were non-signifcantly correlated. Nearly all cSSRs were composed of two microsatellites, which showed no biasedness to a particular motif. Motif duplication pattern, such as, (C)-x-(C), (TG)- x-(TG), (AT)-x-(AT), (TC)- x-(TC) and self-complementary motifs, such as (GC)-x-(CG), (TC)-x-(AG), (GT)-x-(CA) and (TC)-x-(AG) were observed in the cSSRs. -

ICD-9 Diagnosis Codes Effective 10/1/2011 (V29.0) Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

ICD-9 Diagnosis Codes effective 10/1/2011 (v29.0) Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 0010 Cholera d/t vib cholerae 00801 Int inf e coli entrpath 01086 Prim prg TB NEC-oth test 0011 Cholera d/t vib el tor 00802 Int inf e coli entrtoxgn 01090 Primary TB NOS-unspec 0019 Cholera NOS 00803 Int inf e coli entrnvsv 01091 Primary TB NOS-no exam 0020 Typhoid fever 00804 Int inf e coli entrhmrg 01092 Primary TB NOS-exam unkn 0021 Paratyphoid fever a 00809 Int inf e coli spcf NEC 01093 Primary TB NOS-micro dx 0022 Paratyphoid fever b 0081 Arizona enteritis 01094 Primary TB NOS-cult dx 0023 Paratyphoid fever c 0082 Aerobacter enteritis 01095 Primary TB NOS-histo dx 0029 Paratyphoid fever NOS 0083 Proteus enteritis 01096 Primary TB NOS-oth test 0030 Salmonella enteritis 00841 Staphylococc enteritis 01100 TB lung infiltr-unspec 0031 Salmonella septicemia 00842 Pseudomonas enteritis 01101 TB lung infiltr-no exam 00320 Local salmonella inf NOS 00843 Int infec campylobacter 01102 TB lung infiltr-exm unkn 00321 Salmonella meningitis 00844 Int inf yrsnia entrcltca 01103 TB lung infiltr-micro dx 00322 Salmonella pneumonia 00845 Int inf clstrdium dfcile 01104 TB lung infiltr-cult dx 00323 Salmonella arthritis 00846 Intes infec oth anerobes 01105 TB lung infiltr-histo dx 00324 Salmonella osteomyelitis 00847 Int inf oth grm neg bctr 01106 TB lung infiltr-oth test 00329 Local salmonella inf NEC 00849 Bacterial enteritis NEC 01110 TB lung nodular-unspec 0038 Salmonella infection NEC 0085 Bacterial enteritis NOS 01111 TB lung nodular-no exam 0039 -

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

Crimean-Congo Importance Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is caused by a zoonotic virus that Hemorrhagic seems to be carried asymptomatically in animals but can be a serious threat to humans. This disease typically begins as a nonspecific flu-like illness, but some cases Fever progress to a severe, life-threatening hemorrhagic syndrome. Intensive supportive care is required in serious cases, and the value of antiviral agents such as ribavirin is Congo Fever, still unclear. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) is widely distributed Central Asian Hemorrhagic Fever, in the Eastern Hemisphere. However, it can circulate for years without being Uzbekistan hemorrhagic fever recognized, as subclinical infections and mild cases seem to be relatively common, and sporadic severe cases can be misdiagnosed as hemorrhagic illnesses caused by Hungribta (blood taking), other organisms. In recent years, the presence of CCHFV has been recognized in a Khunymuny (nose bleeding), number of countries for the first time. Karakhalak (black death) Etiology Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever is caused by Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic Last Updated: March 2019 fever virus (CCHFV), a member of the genus Orthonairovirus in the family Nairoviridae and order Bunyavirales. CCHFV belongs to the CCHF serogroup, which also includes viruses such as Tofla virus and Hazara virus. Six or seven major genetic clades of CCHFV have been recognized. Some strains, such as the AP92 strain in Greece and related viruses in Turkey, might be less virulent than others. Species Affected CCHFV has been isolated from domesticated and wild mammals including cattle, sheep, goats, water buffalo, hares (e.g., the European hare, Lepus europaeus), African hedgehogs (Erinaceus albiventris) and multimammate mice (Mastomys spp.). -

Characterization of the Rubella Virus Nonstructural Protease Domain and Its Cleavage Site

JOURNAL OF VIROLOGY, July 1996, p. 4707–4713 Vol. 70, No. 7 0022-538X/96/$04.0010 Copyright q 1996, American Society for Microbiology Characterization of the Rubella Virus Nonstructural Protease Domain and Its Cleavage Site 1 2 2 1 JUN-PING CHEN, JAMES H. STRAUSS, ELLEN G. STRAUSS, AND TERYL K. FREY * Department of Biology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia 30303,1 and Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 911252 Received 27 October 1995/Accepted 3 April 1996 The region of the rubella virus nonstructural open reading frame that contains the papain-like cysteine protease domain and its cleavage site was expressed with a Sindbis virus vector. Cys-1151 has previously been shown to be required for the activity of the protease (L. D. Marr, C.-Y. Wang, and T. K. Frey, Virology 198:586–592, 1994). Here we show that His-1272 is also necessary for protease activity, consistent with the active site of the enzyme being composed of a catalytic dyad consisting of Cys-1151 and His-1272. By means of radiochemical amino acid sequencing, the site in the polyprotein cleaved by the nonstructural protease was found to follow Gly-1300 in the sequence Gly-1299–Gly-1300–Gly-1301. Mutagenesis studies demonstrated that change of Gly-1300 to alanine or valine abrogated cleavage. In contrast, Gly-1299 and Gly-1301 could be changed to alanine with retention of cleavage, but a change to valine abrogated cleavage. Coexpression of a construct that contains a cleavage site mutation (to serve as a protease) together with a construct that contains a protease mutation (to serve as a substrate) failed to reveal trans cleavage. -

Measles and Rubella Initiative Outbreak Response Fund Application Standard Operating Procedures

M&RI SOP Feb 24, 2020 Final Measles and Rubella Initiative Outbreak Response Fund Application Standard Operating Procedures This update of the M&RI ORF Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) includes the following modifications: 1. To encourage countries to submit applications for ORF support early in the evolution of the outbreak in order to effectively stop measles virus transmission before it becomes more widespread, M&RI will monitor indicators of timeliness of outbreak response immunization in accordance with Immunization Agenda 2030 guidelines; 2. To accelerate the process to receive support, M&RI has removed requirements for advance notification when requesting ORF support and has established a limited timeframe to evaluate the application for ORF support and to provide feedback or issue a decision letter; 3. To more comprehensively address outbreak response linked to timely and efficient use of vaccine, M&RI will allow for greater flexibility in areas of support on an exceptional basis and with adequate justification; 4. To reduce the likelihood of requested additional information or clarifications from M&RI, the SOPs provide greater detail regarding the key data elements and analysis recommended when investigating measles outbreaks and preparing reports, plans and budgets; 5. To maximize use of outbreak investigations and their follow up to strengthen immunization systems, M&RI requests countries to include findings from root cause analyses and, based on these, plans to improve routine immunization, surveillance and outbreak preparedness in the required post-outbreak report. A. Background The Measles and Rubella Initiative (M&RI) has provided funding through an outbreak response fund (ORF) since 2012 to support bundled vaccine and operational costs for measles and rubella outbreak response immunization (ORI), with Gavi supporting up to a total of US$10 million per year for Gavi-eligible countries. -

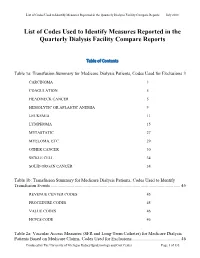

List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the QDFC

List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports July 2018 List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports Table of Contents Table 1a: Transfusion Summary for Medicare Dialysis Patients, Codes Used for Exclusions 3 CARCINOMA 3 COAGULATION 5 HEAD/NECK CANCER 5 HEMOLYTIC OR APLASTIC ANEMIA 9 LEUKEMIA 11 LYMPHOMA 15 METASTATIC 27 MYELOMA, ETC. 29 OTHER CANCER 30 SICKLE CELL 34 SOLID ORGAN CANCER 34 Table 1b: Transfusion Summary for Medicare Dialysis Patients, Codes Used to Identify Transfusion Events .................................................................................................................. 45 REVENUE CENTER CODES 45 PROCEDURE CODES 45 VALUE CODES 46 HCPCS CODE 46 Table 2a: Vascular Access Measures (SFR and Long-Term Catheter) for Medicare Dialysis Patients Based on Medicare Claims, Codes Used for Exclusions ........................................... 46 Produced by The University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center Page 1 of 135 List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports July 2018 COMA 46 END STAGE LIVER DISEASE 48 METASTATIC CANCER 48 Table 2b: Standardized Fistulae Rate (SFR) for Medicare Dialysis Patients Based on Medicare Claims, Codes Used for Prevalent Comorbidities Adjusted in Model .................................... 50 ANEMIA 50 CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE 52 CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE 55 CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE 56 CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE 68 DIABETES 69 DRUG DEPENDENCE 79 INFECTIONS (NON-VASCULAR ACCESS-RELATED): 93 PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASE (INCLUDES ARTERIAL, VENOUS AND NONSPECIFIC DISEASES) 124 Table 3: Dialysis Adequacy ................................................................................................... -

Client Services Manual Public Health Laboratory

CLIENT SERVICES MANUAL PUBLIC HEALTH LABORATORY COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA 2220 MOORPARK AVE, 2ND FLOOR SAN JOSE, CA 95128 (P) 408.885.4272 | (F) 408.885.4275 http://www.sccgov.org/sites /sccphd/en-us/HealthProviders/Lab Patricia Dadone, Public Health Laboratory Director Sara H. Cody, MD, Health Officer and Public Health Director Table of Contents 1 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................................... 1.1 ROLE .............................................................................................................................................................. 1.1 MISSION STATEMENT ..................................................................................................................................... 1.1 ABBREVIATIONS.............................................................................................................................................. 1.2 LABORATORY CERTIFICATIONS ........................................................................................................................ 1.4 CLIENT SERVICES ............................................................................................................................................ 1.5 Hours of Operation: .............................................................................................................................. 1.5 Supplies .................................................................................................................................................. -

Modulation of NF-Κb Signalling by Microbial Pathogens

REVIEWS Modulation of NF‑κB signalling by microbial pathogens Masmudur M. Rahman and Grant McFadden Abstract | The nuclear factor-κB (NF‑κB) family of transcription factors plays a central part in the host response to infection by microbial pathogens, by orchestrating the innate and acquired host immune responses. The NF‑κB proteins are activated by diverse signalling pathways that originate from many different cellular receptors and sensors. Many successful pathogens have acquired sophisticated mechanisms to regulate the NF‑κB signalling pathways by deploying subversive proteins or hijacking the host signalling molecules. Here, we describe the mechanisms by which viruses and bacteria micromanage the host NF‑κB signalling circuitry to favour the continued survival of the pathogen. The nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) family of transcription Signalling targets upstream of NF‑κB factors regulates the expression of hundreds of genes that NF-κB proteins are tightly regulated in both the cyto- are associated with diverse cellular processes, such as pro- plasm and the nucleus6. Under normal physiological liferation, differentiation and death, as well as innate and conditions, NF‑κB complexes remain inactive in the adaptive immune responses. The mammalian NF‑κB cytoplasm through a direct interaction with proteins proteins are members of the Rel domain-containing pro- of the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) family, including IκBα, tein family: RELA (also known as p65), RELB, c‑REL, IκBβ and IκBε (also known as NF-κBIα, NF-κBIβ and the NF-κB p105 subunit (also known as NF‑κB1; which NF-κBIε, respectively); IκB proteins mask the nuclear is cleaved into the p50 subunit) and the NF-κB p100 localization domains in the NF‑κB complex, thus subunit (also known as NF‑κB2; which is cleaved into retaining the transcription complex in the cytoplasm.