Painting As Praxis ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

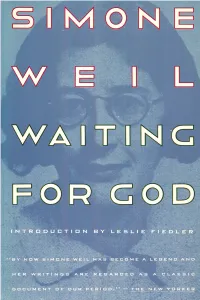

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Damien Hirst Visual Candy and Natural History

G A G O S I A N 7 February 2018 DAMIEN HIRST VISUAL CANDY AND NATURAL HISTORY EXTENDED! Through Saturday, March 3, 2018 7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street Central, Hong Kong I had my stomach pumped as a child because I ate pills thinking they were sweets […] I can’t understand why some people believe completely in medicine and not in art, without questioning either. —Damien Hirst Gagosian is pleased to present “Visual Candy and Natural History,” a selection of paintings and sculptures by Damien Hirst from the early- to mid-1990s. The exhibition coincides with Hirst’s most ambitious and complex project to date, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,” on view at Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice until December 3. Since emerging onto the international art scene in the late 1980s as the protagonist of a generation of British artists, Hirst has created installations, sculptures, paintings and drawings that examine the complex relationships between art, beauty, religion, science, life and death. Through series as diverse as the ‘Spot Paintings’, ‘Medicine Cabinets’, ‘Natural History’ and butterfly ‘Kaleidoscope Paintings,’ he has investigated and challenged contemporary belief systems, tracing the uncertainties that lie at the heart of human experience. This exhibition juxtaposes the joyful, colorful abstractions of his ‘Visual Candy’ paintings with the clinical forms of his ‘Natural History’ sculptures. Page 1 of 3 The ‘Visual Candy’ paintings allude to movements including Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, while the ‘Natural History’ sculptures—glass tanks containing biological specimens preserved in formaldehyde—reflect the visceral realities of scientific investigation through minimalist design. -

THBT Social Disgust Is Legitimate Grounds for Restriction of Artistic Expression

Published on idebate.org (http://idebate.org) Home > THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression The history of art is full of pieces which, at various points in time, have caused controversy, or sparked social disgust. The works most likely to provoke disgust are those that break taboos surrounding death, religion and sexual norms. Often, the debate around whether a piece is too ‘disgusting’ is interwoven with debate about whether that piece actually constitutes a work of art: people seem more willing to accept taboo-breaking pieces if they are within a clearly ‘artistic’ context (compare, for example, reactions to Michelangelo’s David with reactions to nudity elsewhere in society). As a consequence, the debate on the acceptability of shocking pieces has been tied up, at least in recent times, with the debate surrounding the acceptability of ‘conceptual art’ as art at all. Conceptual art1 is that which places an idea or concept (rather than visual effect) at the centre of the work. Marchel Duchamp is ordinarily considered to have begun the march towards acceptance of conceptual art, with his most famous piece, Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”. It is popularly associated with the Turner Prize and the Young British Artists. This debate has a degree of scope with regards to the extent of the restriction of artistic expression that might be being considered here. Possible restrictions include: limiting display of some pieces of art to private collections only; withdrawing public funding (e.g. -

The Theory and Practice of Visual Arts Marketing

The Tension Between Artistic and Market Orientation in Visual Art Dr Ian Fillis Department of Marketing University of Stirling Stirling Scotland FK9 4LA Email: [email protected] Introduction For centuries, artists have existed in a world which has been shaped in part by their own attitudes towards art but which also co-exists within the confines of a market structure. Many artists have thrived under the conventional notion of a market with its origins in economics and supply and demand, while others have created a market for their work through their own entrepreneurial endeavours. This chapter will explore the options open to the visual artist and examine how existing marketing theory often fails to explain how and why the artist develops an individualistic form of marketing where the self and the artwork are just as important as the audience and the customer. It builds on previous work which examines the theory and practice of visual arts marketing, noting that there has been little account taken of the philosophical clashes of art for art’s sake versus business sake (Fillis 2004a). Market orientation has received a large amount of attention in the marketing literature but product centred marketing has largely been ignored. Visual art has long been a domain where product and artist centred marketing have been practiced successfully and yet relatively little has been written about its critical importance to arts marketing theory. The merits and implications of being prepared to ignore market demand and customer wishes are considered here. 1 Slater (2007) carries out an investigation into understanding the motivations of visitors to galleries and concludes that, rather than focusing on personal and social factors alone, recognition of the role of psychological factors such as beliefs, values and motivations is also important. -

Higher National Unit Specification General Information Unit Title: Body Painting Skills for Make-Up Artists (SCQF Level 7) Unit

Higher National Unit Specification General information Unit title: Body Painting Skills for Make-up Artists (SCQF level 7) Unit code: J1N4 34 Superclass: LE Publication date: September 2020 Source: Scottish Qualifications Authority Version: 02 Unit purpose This unit is designed to enable learners to develop make-up skills appropriate to body painting and is ideal for learners following a career in the make-up artistry industry. Learners will research a variety of body painting techniques to include freehand and airbrushing and demonstrate a high level of creativity and imagination within their body painting designs and finished looks. Outcomes On successful completion of the unit the learner will be able to: 1 Research body painting looks, products, equipment and current application techniques. 2 Plan a range of body painting looks incorporating current application techniques. 3 Perform the planned body painting looks to include product removal and aftercare advice. Credit points and level 1 Higher National Unit credit at SCQF level 7: (8 SCQF credit points at SCQF level 7) Recommended entry to the unit Entry to this unit is at the discretion of the centre. However, it is recommended that learners should have knowledge of basic design principles and the practical aptitude and dexterity to apply the products and techniques involved in body painting. J1N4 34, Body Painting Skills for Make-up Artists (SCQF level 7) 1 Higher National Unit Specification: General information (cont) Unit title: Body Painting Skills for Make-up Artists (SCQF level 7) Core Skills Achievement of this Unit gives automatic certification of the following Core Skills component: Core Skill component Critical Thinking at SCQF level 5 Planning and Organising at SCQF level 5 There are also opportunities to develop aspects of Core Skills which are highlighted in the Support Notes of this Unit specification. -

Chapter 55 Unified Development Code

Code of Ordinances City of Ann Arbor, Michigan Chapter 55 Unified Development Code Adopted: July 16, 2018 With Amendments Through: February 14, 2021 Supplement History Table Ordinance No. Date Adopted Effective Date ORD-18-06 7-16-2018 7-26-2018 ORD-18-20 8-23-2018 10-31-2018 ORD-18-22 8-23-2018 11-4-2018 ORD-19-15 6-3-2019 6-16-2019 ORD-19-16 6-3-2019 6-16-2019 ORD-19-17 7-1-2019 7-21-2019 ORD-19-26 8-19-2019 9-22-2019 ORD-19-27 9-3-2019 9-22-2019 ORD-19-28 9-3-2019 9-2019 ORD-19-32 10-7-2019 10-27-2019 ORD-19-34 11-4-2019 11-17-2019 ORD-20-18 6-6-2020 7-19-2020 ORD-20-27 12-7-2020 12-20-2020 ORD-20-30 12-21-2020 1-10-2021 ORD-20-33 1-4-21 1-31-2021 ORD-20-34 1-19-21 2-14-2021 ORD-20-35 1-19-21 2-14-2021 With Amendments Through: February 14, 2021 Page 2 Chapter 55 ............................................................................................................................ 10 Ann Arbor Unified Development Code .......................................................................... 10 Article I: General Provisions ............................................................................................ 10 5.1 Authority ...............................................................................................................................10 5.2 Title ........................................................................................................................................10 5.3 Effective Date .......................................................................................................................10 -

817 Adult Uses

817. ADULT USES 817.010. DEFINITIONS. (A) Adult Uses. Adult uses include adult book stores, adult motion picture theatres, adult mini-motion picture theatres, adult massage parlors, adult steam room/bathhouse/sauna facilities, adult companionship establishments, adult rap/conversation parlors, adult health/sport clubs, adult cabarets, adult novelty businesses, adult motion picture arcades, adult modeling studios, adult hotels/motels, adult body painting studios, and other premises, enterprises, establishments, businesses or places open to some or all members of the public, at or in which there is an emphasis on the presentation, display, depiction or description of "specified sexual activities" or "specified anatomical areas" which are capable of being seem by members of the public. Activities classified as obscene as defined by Minnesota Statutes 617.241 are not included. (B) Adult Use - Accessory. The offering of goods and/or services which are classified as adult uses on a limited scale and which are incidental to the primary activity and goods and/or services offered by the establishment. Examples of such items include adult magazines, adult movies, adult novelties, and the like. (C) Adult Uses - Principal. The offering of goods and/or services which are classified as adult uses as a primary or sole activity of a business or establishment and include but are not limited to the following: 1. Adult Use - Body Painting Studio. An establishment or business which provides the service of applying paint or other substance, whether transparent or non-transparent, to or on the body of a patron when such body is wholly or partially nude in terms of "specified anatomical areas". -

Pissing in the Pleasure Garden

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2021 Pissing in the Pleasure Garden Ellen Hanson Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons © Ellen Hanson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6681 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Ellen Rebecca Hanson 2021 All Rights Reserved 1 PISSING IN THE PLEASURE GARDEN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art at Virginia Commonwealth University By Ellen Hanson Bachelor of Arts, Bennington College 2014 Master of Fine Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University 2021 Director: Caitlin Cherry Assistant Professor, Department of Painting and Printmaking Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May, 2021 2 Acknowledgements Thanks to my VCU PAPR committee and community: Caitlin Cherry, Hilary Wilder, Cara Benedetto, Noah Simblist, Hope Ginsburg, Evan Garza, Damien Ding, Raul Aguilar, Connor Stankard, Kelley-Ann Lindo, Hanaa Safwat, John Chae, Luis Vasquez La Roche, GM Keaton, Sydney Finch, Bryan Castro, Seren Moran, Kyrae Dawaun, Juliana Bustillo, Eleanor Thorp, Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, and Ekaterina Muromtseva Special thanks to my family: Katherine -

BRIGHT LIGHTS James W. Hyams Published by the Eleanor D

BRIGHT LIGHTS James W. Hyams Published by the Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University, Roanoke, Virginia. hollins.edu/museum • 540/362-6532 Photography: Jeff Hofmann Design: Laura Jane Ramsburg This exhibition is sponsored in part by the City of Roanoke through the Roanoke Arts Commission. BRIGHT LIGHTS James W. Hyams January 18 - March 25, 2018 Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University CONTENTS 3 Director’s Note Jenine Culligan 4 How to Become an Accidental Art Collector and Alleged Artist James W. Hyams 7 Casual Observations of an Interested Neighbor Bill Rutherfoord 28 Acknowledgements James W. Hyams Director’s Note Jenine Culligan The art-collecting bug bit Jim Hyams early and hard. Over his lifetime, he has carefully chosen an astounding collection of prints by the most important international contemporary artists. Surrounded by art in his museum-like home, Jim absorbs—and is inspired by—this work on a daily basis. Living with and loving art can be an end in itself, but sharing your collection and educating people about art is another; in this, Jim has been deeply thoughtful and generous. The Eleanor D. Wilson Museum has enjoyed a close association with Jim since the summer of 2005 when Photorealist Prints from the James W. Hyams Collection was displayed, followed in 2008 with Print as Muse: Reflections on Vanitas from the James W. Hyams Collection. Jim has been generous in donating art to the museum’s collection as well, with a print by Ron Kleeman and a mixed media work by Robert Kushner. The Eleanor D. Wilson Museum is pleased to exhibit these ten sculptures created by Jim Hyams, displayed in homage alongside the work that inspired him. -

Sexual Oriented Businesses (Pdf)

ARTICLE 2 DEFINITIONS 5.2 Definitions. For the purpose of this Chapter, certain terms or words used herein shall be interpreted as follows: The word "person" includes a firm, association, organization, partnership, trust, company or corporation as well as an individual; the present tense includes the future tense; the singular number includes the plural and the plural number includes the singular; the word "shall" is mandatory, the word "may" is permissive; the words "used" or "occupied" include the words "intended," "designed," or "arranged to be used or occupied." Terms not herein defined shall have the meaning customarily assigned to them. 5.3 Definitions (A-B) For the purpose of this Chapter, certain terms are herewith defined: (1) Adult Arcade: Any place to which the public is permitted or invited which coin-operated, slug operated, or for any form of consideration, or electronically, electrically or mechanically controlled still or motion-picture machines, projectors, video or laser disc players, or other image-producing devices are maintained to show images to five or fewer persons per machine at any one time, and where the images so displayed are distinguished or characterized by the depicting or describing of specified sexual activities or specified anatomical areas. (2) Adult Booth: A partitioned area of less than 100 square feet inside an adult regulated use which is: (a) Designed or regularly used for the viewing of books, magazines, periodicals, or other printed matter, photographs, films, motion-pictures, video cassettes, slides, or other visual representations, recordings, and novelties or devices including which are distinguished or characterized by their emphasis on matter depicting, describing, or relating to specified sexual activities or specified anatomical areas by one or more persons. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.18316/rcd.v9i17.3742 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Adams, R. (2017). 'The Saatchi Generation': Art and Advertising in the UK in the Late 20th Century. Conhecimento & Diversidade, 9(17), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.18316/rcd.v9i17.3742 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Download List of Works

CONTEMPORARY MASTERS Edition 2019 CHRIS LEVINE Lightness of Being (2011) Fluro screenprint on paper Unique Artist Proof Dimensions 105 x 85 cm Compassion Lightness of Being – Blue Archival inkjet print Archival inkjet print Limited Edition of 500 Limited Edition of 200 Dimensions 40 x 29.7 cm Dimensions 41 x 30 cm 1 2 DAMIEN HIRST Psalm - Domine, Dominus Noster Psalm – Verba Mea Auribus Silkscreen print with glaze Silkscreen print with glaze Limited Edition of 25 Limited Edition of 25 Dimensions 74 x 71.4 cm Dimensions 74 x 71.4 cm 3 4 DAMIEN HIRST For The Love of God Silkscreen with Diamond Dust Limited Edition of 1000 Dimensions 33 x 24 cm Prosperity Providence Colour etching on wove paper Colour etching on wove paper Limited Edition of 45 Limited Edition of 45 Dimensions 47 x 39 cm Dimensions 47 x 39 cm 5 6 DAMIEN HIRST Fear of Flying Original drawing on paper Dimensions 27 x 31.5 cm 7 8 MARC QUINN Internal Labyrinth Embossed Woodcut on Somerset Limited Edition of 75 Dimensions 80 x 80 cm Chromosphere Heliosphere Pigment print with silkscreen glaze Pigment print with silkscreen glaze Limited Edition of 75 Limited Edition of 75 Dimensions 80 x 80 cm Dimensions 80 x 80 cm 9 10 Art is like a lover whom you run away from but “ who comes back and picks you up Tracey Emin ” TRACEY EMIN Birds (Left) Believe in Extraordinary (Centre) True Love Always Wins (Right) Lithograph printed on Somerset Limited Edition of 300 Dimensions 76 x 60 cm 11 12 TRACEY EMIN I Think of You Inside Your Heart Lithographic print on Somerset Lithographic print on