Sublime Dissension: a Working-Class Anti-Pygmalion Aesthetics of the Female Grotesque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BFI Film Fund

BFI FILM FUND FILMS 2013/14 20,000 DAYS ON EARTH 45 YEARS ’71 ALAN PARTRIDGE: ALPHA PAPA BELLE BROKEN BROOKLYN BYPASS CATCH 05 ME DADDY CALVARY THE COMEDIAN CUBAN FURY DARK HORSE THE DOUBLE THE DUKE OF BURGUNDY ELECTRICITY EXHIBITION THE FALLING FRANK FOR ISSUE 1 THOSE IN PERIL GET SANTA GONE TOO FAR THE GOOB SPRING/SUMMER 2014 HALF OF A YELLOW SUN HOW I LIVE NOW HYENA 06 04 MIKE LEIGH INREALLIFE THE INVISIBLE WOMAN JIMMY’S HALL THE On Cannes and filmmaking 05 STEPHEN BERESFORD AND LAST DAYS ON MARS THE LAST PASSENGER THE LOUISE OSMOND LOBSTER LE WEEK-END MISTER JOHN MR. TURNER Bringing real life to the big screen ROBOT OVERLORDS A PERVERT’S GUIDE TO IDEOLOGY 06 PETER STRICKLAND On experience, insecurity and PHILOMENA PRIDE QUEEN & COUNTRY REMAINDER THE not knowing 08 RIOT CLUB SECOND COMING THE SELFISH GIANT SHELL 08 DREAM WORLD SLOW WEST SPIKE ISLAND THE SPIRIT OF ’45 A STORY Creating Carol Morley’s The Falling 10 HOME SWEET HOME OF CHILDREN & FILM THE STUART HALL PROJECT Filmmaking outside the big smoke SUFFRAGETTE SUNSET SONG SUNSHINE ON LEITH UNDER THE SKIN WELCOME TO THE PUNCH X PLUS Y 10 CoveR image: CaRol moRley, Photo By Paul maRC mitChell BFI Film Fund Welcome... to the first edition of BFI Film Fund Filmmakers, an up close and personal look at a number of filmmakers who have recently been As the largest public film fund in the UK, the BFI Lottery Film Fund develops, supports and supported by the BFI Film Fund, and films that are just coming into view. -

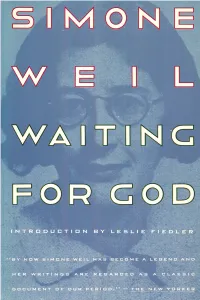

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Londra Al Centro Dell Scena Artistica: La Yung British Art Dalla Conferenza Del 12-05-2011 Del Prof

Londra al centro dell scena artistica: La Yung British Art Dalla conferenza del 12-05-2011 del prof. Francesco Poli a cura del prof. Mario Diegol i Sensation e la YBA (Young British Artists) Il 28 dicembre del 1997 presso la Royal Academy of Art di Londra il collezionista d’arte contemporanea Charles Saatchi organizza la mostra Sensation in cui espone le opere della Yung British Art. La mostra è, in seguito, riproposta a Berl ino e New York e diventa, grazie all’abilità manageriale di Saatchi e alla sua rete di contatt i sviluppata negl i anni precedenti con la sua att ività di pubbl icitario, l’evento artistico del momento e un riferimento importante per il mercato dell’arte portando alla ribalta una serie di giovani art isti inglesi come: Jake & Dinos Chapman, Adam Chodzko, Mat Coll ishaw, Tracey Emin, Marcus Harvey, Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Michael Landy, Abigail Lane, Sarah Lucas, Chris Ofil i, Richard Patterson, Simon Patterson, Marc Quinn, Fiona Rae, Sam Taylor-Wood, Gavin Turk, Gill ian Wearing, Rachel Whiteread. Gl i artist i della Yung British Art propongono opere che sol itamente tendono a stupire e a provocare lo spettatore. Sono giovani nati negl i anni sessanta che impiegano linguaggi differenti non sempre omologabil i alle tradizional i espressioni plastiche e visive anche se ne recuperano a volte i material i (la pittura, la scultura in marmo) mischiandoli o alternandol i all’impiego di oggetti, fotograf ie, material i plastici, stoffe ecc.. Il manifesto della mostra Sensation con cui evocano e amplificano storie personal i e collettive dove il soggetto e il contenuto prevalgono sulla forma: una forma a volte iperreal istica, in altri casi mostruosa e raccapricciante ampl ificata da dimensioni che possono assumere una scala monumentale. -

November 2013 Free Entry Hurvin Anderson Reporting Back

Programme September – November 2013 www.ikon-gallery.co.uk Free entry Hurvin Anderson reporting back Exhibition 25 September – 10 November 2013 First and Second Floor Galleries Ikon presents the most comprehensive exhibition to as ‘slightly outside of things’. Later paintings of the date of paintings by Birmingham-born artist Hurvin Caribbean embody this kind of perception with Anderson (born 1965), evoking sensations of being verdant green colour glimpsed behind close-up caught between one place and another, drawn from details of the fences and security grilles found in personal experience. It surveys the artist’s career, residential areas, or an expanse of water or desolate including work made while at the Royal College of approach separating us, the viewer, from the point Art, London, in 1998, through the acclaimed Peter’s of interest in the centre ground. 1 series, inspired by his upbringing in Birmingham’s Afro-Caribbean community, and ongoing works Anderson’s method of composition signifies at arising out of time spent in Trinidad in 2002. Filling once a kind of social and political segregation, a 2 Ikon’s entire exhibition space, reporting back traces the smartness with respect to the business of picture development of Anderson’s distinct figurative style. making, amounting to a kind of semi-detached apprehension of what he encounters. Anderson arrived on the international art scene with Peter’s, an ongoing series of paintings depicting the A catalogue accompanies the exhibition priced interiors of barbers’ shops, in particular one (owned £20, special exhibition price £15. It includes an essay by Peter Brown) visited by Anderson with his father by Jennifer Higgie, writer and co-editor of Frieze. -

Damien Hirst Visual Candy and Natural History

G A G O S I A N 7 February 2018 DAMIEN HIRST VISUAL CANDY AND NATURAL HISTORY EXTENDED! Through Saturday, March 3, 2018 7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street Central, Hong Kong I had my stomach pumped as a child because I ate pills thinking they were sweets […] I can’t understand why some people believe completely in medicine and not in art, without questioning either. —Damien Hirst Gagosian is pleased to present “Visual Candy and Natural History,” a selection of paintings and sculptures by Damien Hirst from the early- to mid-1990s. The exhibition coincides with Hirst’s most ambitious and complex project to date, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,” on view at Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice until December 3. Since emerging onto the international art scene in the late 1980s as the protagonist of a generation of British artists, Hirst has created installations, sculptures, paintings and drawings that examine the complex relationships between art, beauty, religion, science, life and death. Through series as diverse as the ‘Spot Paintings’, ‘Medicine Cabinets’, ‘Natural History’ and butterfly ‘Kaleidoscope Paintings,’ he has investigated and challenged contemporary belief systems, tracing the uncertainties that lie at the heart of human experience. This exhibition juxtaposes the joyful, colorful abstractions of his ‘Visual Candy’ paintings with the clinical forms of his ‘Natural History’ sculptures. Page 1 of 3 The ‘Visual Candy’ paintings allude to movements including Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, while the ‘Natural History’ sculptures—glass tanks containing biological specimens preserved in formaldehyde—reflect the visceral realities of scientific investigation through minimalist design. -

Chapman for the Duo’S Retrospective in Istanbul Which Had Been on Display During 10/2/2017-7/5/2017

This article was commissioned by the art gallery ARTER (Istanbul, Turkey) and the artists Jake & Dinos Chapman for the duo’s retrospective in Istanbul which had been on display during 10/2/2017-7/5/2017. For further information on the show, please click here. Reviewed by the artists and the editors of the exhibition monograph, this essay was originally written in English. Both the English original and the Turkish translation was published in this monograph. In line with the commissioning brief, the article attempts to provide a critical review of the Chapmans’ art practice while also locating the duo’s artworks within an original theoretical framework. Jake & Dinos Chapman ANLAMSIZLIK ÂLEMİNDE — IN THE REALM OF THE SENSELESS CHAPMAN 23-01-17.indd 3 23.01.2017 17:59 Jake & Dinos Chapman Anlamsızlık Âleminde In the Realm of the Senseless Genel Yayın Yönetmeni | Editor-in-Chief Bu yayın, Jake ve Dinos Chapman’ın Arter’de 10 Şubat–7 Mayıs İlkay Baliç 2017 tarihleri arasında gerçekleşen “Anlamsızlık Âleminde” adlı sergisine eşlik etmektedir. Editör | Editor Süreyyya Evren This book accompanies Jake and Dinos Chapman’s exhibition “In the Realm of the Senseless” held at Arter between İngilizceden Türkçeye çeviri 10 February and 7 May 2017. Translation from English to Turkish Süreyyya Evren [12-15] Anlamsızlık Âleminde Özge Çelik - Orhan Kılıç [22-27] In the Realm of the Senseless Zafer Aracagök [34-45] Jake & Dinos Chapman Münevver Çelik - Sinem Özer [60-75] 10/02–07/05/2017 Küratör | Curator: Nick Hackworth Türkçe düzelti | Turkish proofreading Emre Ayvaz Teşekkürler | Acknowledgements İngilizce düzelti | English proofreading Hussam Otaibi Anna Knight ve tüm Floreat ekibi | and everyone at Floreat John McEnroe Gallery Inc. -

THBT Social Disgust Is Legitimate Grounds for Restriction of Artistic Expression

Published on idebate.org (http://idebate.org) Home > THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression The history of art is full of pieces which, at various points in time, have caused controversy, or sparked social disgust. The works most likely to provoke disgust are those that break taboos surrounding death, religion and sexual norms. Often, the debate around whether a piece is too ‘disgusting’ is interwoven with debate about whether that piece actually constitutes a work of art: people seem more willing to accept taboo-breaking pieces if they are within a clearly ‘artistic’ context (compare, for example, reactions to Michelangelo’s David with reactions to nudity elsewhere in society). As a consequence, the debate on the acceptability of shocking pieces has been tied up, at least in recent times, with the debate surrounding the acceptability of ‘conceptual art’ as art at all. Conceptual art1 is that which places an idea or concept (rather than visual effect) at the centre of the work. Marchel Duchamp is ordinarily considered to have begun the march towards acceptance of conceptual art, with his most famous piece, Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”. It is popularly associated with the Turner Prize and the Young British Artists. This debate has a degree of scope with regards to the extent of the restriction of artistic expression that might be being considered here. Possible restrictions include: limiting display of some pieces of art to private collections only; withdrawing public funding (e.g. -

Richard Billingham Writer/Director

Richard Billingham Writer/Director Richard is a Turner Prize-shortlisted artist and photographer who has also been working for many years on film and video, including the acclaimed BBC documentary FISHTANK and the art installation ZOO. Richard won the Douglas Hickox Award for best new director at the 2018 BIFAs for RAY & LIZ, his searing, brilliant portrayal of dysfunctional but deeply human working-class life and has been nominated for a National Film Award for best director and a BAFTA for Outstanding Debut. Film 2020 AT HAWTHORNE TIME Writer/Director Adaptation of the novel by Melissa Harrison in Development with the BFI 2018 RAY & LIZ Writer/Director Produced by Jacqui Davies in association with Severn Screen Starring Michelle Bonnard, Richard Ashton BAFTA Nomination, Ray & Liz, Best Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer National Film Awards UK Nomination, Ray & Liz, Best Director Douglas Hickox Award, Best Debut Director, Ray & Liz, British Independent Film IWC Schaffhausen Filmmaker Bursary Award in association with the BFI Special Mention, Ray & Liz, Locarno Film Festival Silver Star Award for Narrative Film, Ray & Liz, El Gouna Film Festival, Egypt Golden Alexander Award, Best Film, Ray & Liz, Thessaloniki Film Festival Best Film & Best Actress, Ray & Liz, Batumi International Art House Film Festival Grand Jury Award, Ray & Liz, Seville Film Festival Grand Jury Award, Best Director, Ray & Liz, Lisbon and Sintra Film Festival Special Mention, Ray & Liz, Festival Du Nouveau Cinema, Montreal Wakelin Award, Glynn Vivian Gallery, Swansea Creative Wales Award Documentaries 1998 FISHTANK Commissioned by ArtAngel and Adam Curtis for BBC Television New York Video Festival Visions Du Reel - Festival international de cinema, Nyon, Switzerland 11th International Film Festival of Marseille Electric Cinema, Birmingham, UK Diagonale Festival of Austrian Film International Film Festival, Rotterdam Broadcast on Arte, France Selected Bibliography Patrick Gamble, ‘Ray & Liz, Richard Billingham’, Kinoscope, 28th Dec. -

The Theory and Practice of Visual Arts Marketing

The Tension Between Artistic and Market Orientation in Visual Art Dr Ian Fillis Department of Marketing University of Stirling Stirling Scotland FK9 4LA Email: [email protected] Introduction For centuries, artists have existed in a world which has been shaped in part by their own attitudes towards art but which also co-exists within the confines of a market structure. Many artists have thrived under the conventional notion of a market with its origins in economics and supply and demand, while others have created a market for their work through their own entrepreneurial endeavours. This chapter will explore the options open to the visual artist and examine how existing marketing theory often fails to explain how and why the artist develops an individualistic form of marketing where the self and the artwork are just as important as the audience and the customer. It builds on previous work which examines the theory and practice of visual arts marketing, noting that there has been little account taken of the philosophical clashes of art for art’s sake versus business sake (Fillis 2004a). Market orientation has received a large amount of attention in the marketing literature but product centred marketing has largely been ignored. Visual art has long been a domain where product and artist centred marketing have been practiced successfully and yet relatively little has been written about its critical importance to arts marketing theory. The merits and implications of being prepared to ignore market demand and customer wishes are considered here. 1 Slater (2007) carries out an investigation into understanding the motivations of visitors to galleries and concludes that, rather than focusing on personal and social factors alone, recognition of the role of psychological factors such as beliefs, values and motivations is also important. -

London Gallery Map Summer 2018 Galleriesnow.Net for Latest Info Visit Galleriesnow.Net

GalleriesNow.net for latest info visit GalleriesNow.net London Gallery Map Summer 2018 21 Jun Impressionist & A Blain|Southern 5E Modern Works on Paper Flowers Gallery, Luxembourg & Dayan 6F Partners & Mucciaccia 6G Repetto Gallery 5F S Simon Lee 5G Sotheby’s S|2 Gallery 5E Victoria Miro Mayfair 5E Kingsland Road 3A Achille Salvagni 28 Jun Handpicked: 50 Sadie Coles HQ ITION Atelier 5F Works Selected by the S Davies Street 5F SUPERIMPO Saatchi Gallery SITION SUPERIMPO 28 Jun Post-War to Present Land of Lads, Land of Lashes 30 Jun–12 Jul Classic Week Upstairs: Charlotte ‘Snapshot’ Aftermath: Art in the Wake of 25 Jun–11 Aug 3 Jul Old Master & British Johannesson 29 Jun–1 Jul World War One Edward Kienholz: America Drawings & Watercolours Ely House, 37 Dover St, 25 May–30 Jun René Magritte (Or: The Rule Superimposition | Paul Michele Zaza Viewing Room: Joel Mesler: Signals 5 Jun–23 Sep Surface Work 28 Cork St, W1S 3NG Morrison, Barry Reigate, My Hometown Lorenzo Vitturi: Money Must W1S 4NJ of Metaphor) 18 May–15 Jun The Alphabet of Creation 27 Apr–13 Jul 11 Apr–16 Jun 4 Jul Treasured Portraits 1-2 Warner Yard, EC1R 5EY 10am-6pm mon-fri, 11am- Michael Stubbs, Mark (for now) Millbank, SW1P 4RG 18 May–14 Jul from the Collection of Ernst Be Made 10am-6pm tue-sat 27 Feb–26 May Apollo 11am-6pm wed-fri, 4pm sat Titchner Nudes 20 Apr–26 May 31 St George St, W1S 2FJ 10am-6pm daily Erkka Nissinen Holzscheiter 11 May–30 Jun 2 Savile Row, W1S 3PA 15 Mar–7 Sep noon-5pm sat 15 Jun–31 Aug 11 Apr–26 May 10am-5pm mon-fri 23 May–14 Jul 5 Jul Old Masters Evening -

Press Release

Institute of Contemporary Arts PRESS RELEASE ICA Artists’ Editions + Paul Stolper Gallery 12 January – 16 February 2019 Opening Friday 11 January, 6–8pm Paul Stolper Gallery Frances Stark, Proposal for a Peace Poster, 2017. Silkscreen print with deboss elements, 67 × 67 cm, Edition of 10 (2AP) ICA Artists’ Editions and Paul Stolper Gallery collaborate for the first time to present a joint exhibition of artists’ editions at Paul Stolper Gallery, opening 12 January 2019. The exhibition showcases a collection of rare editions from Peter Blake, Adam Chodzko, Mat Collishaw, Keith Coventry, Jeremy Deller, Brian Eno, Marcus Harvey, Jenny Holzer, Roger Hiorns, Gary Hume, Sarah Lucas, Vinca Petersen, Peter Saville, Bob and Roberta Smith, Frances Stark, Gavin Turk and Cerith Wyn Evans. The exhibition provides an opportunity to view a selection of important editions from the last 40 years: from Peter Blake’s Art Jak, commissioned by the ICA in 1978 to raise funds for the institution, to Jeremy Deller’s iconic and catalysing print The History of the World, published by Paul Stolper in 1998, to Jenny Holzer’s pivotal Inflammatory Essays, first fly-posted around New York in the late 1970s and then created as an edition for the ICA in 1993. www.ica.art The Mall London SW1Y 5AH +44 (0)20 7930 0493 Tracking the course of editions produced by ground-breaking artists such as Cerith Wyn Evans and Sarah Lucas, the exhibition explores the potential of the format and the numerous ways that artists have engaged with the editioning method of creation. The exhibition is inspired by conversations between Paul Stolper, Stefan Kalmár (ICA Director) and Charlotte Barnard (ICA Artists’ Editions) on the radical history and potential of the editioned artwork, which can free the artist from the demands of their primary practice or gallery expectations. -

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth Cover image: Installation View, Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010–11, 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Sensational Cities, John J.