CULTURAL EVOLUTION a Case Study of Indian Music 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

The Concept of Tala 1N Semi-Classical Music

The Concept of Tala 1n Semi-Classical Music Peter Manuel Writers on Indian music have generally had less difficulty defining tala than raga, which remains a somewhat abstract, intangible entity. Nevertheless, an examination of the concept of tala in Hindustani semi-classical music reveals that, in many cases, tala itself may be a more elusive and abstract construct than is commonly acknowledged, and, in particular, that just as a raga cannot be adequately characterized by a mere schematic of its ascending and descending scales, similarly, the number of matra-s in a tala may be a secondary or even irrelevant feature in the identification of a tala. The treatment of tala in thumri parallels that of raga in thumn; sharing thumri's characteristic folk affinities, regional variety, stress on sentimental expression rather than theoretical complexity, and a distinctively loose and free approach to theoretical structures. The liberal use of alternate notes and the casual approach to raga distinctions in thumri find parallels in the loose and inconsistent nomenclature of light-classical tala-s and the tendency to identify them not by their theoretical matra-count, but instead by less formal criteria like stress patterns. Just as most thumri raga-s have close affinities with and, in many cases, ongms in the diatonic folk modes of North India, so also the tala-s of thumri (viz ., Deepchandi-in its fourteen- and sixteen-beat varieties-Kaharva, Dadra, and Sitarkhani) appear to have derived from folk meters. Again, like the flexible, free thumri raga-s, the folk meters adopted in semi-classical music acquired some, but not all, of the theoretical and structural characteristics of their classical counterparts. -

12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, Vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, Tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, Harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, Tanpuras

From left to right: Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, Shampa Bhattacharya, Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, Michael Harrison, Kedar Naphade Photo credit: Ira Meistrich, edited by Tina Psoinos 12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, tanpuras TRANSCENDENCE Raga Desh: Man Rang Dani, drut bandish in Jhaptal – 9:45 Raga Shahana: Janeman Janeman, madhyalaya bandish in Teental – 14:17 Raga Jhinjhoti: Daata Tumhi Ho, madhyalaya bandish in Rupak tal, Aaj Man Basa Gayee, drut bandish in Teental – 25:01 Raga Bhupali: Deem Dara Dir Dir, tarana in Teental – 4:57 Raga Basant: Geli Geli Andi Andi Dole, drut bandish in Ektal – 9:05 Recorded on 29-30 May, 2015 at Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY Produced and Engineered by Adam Abeshouse Edited, Mixed and Mastered by Adam Abeshouse Co-produced by Shampa Bhattacharya, Michael Harrison and Peter Robles Sponsored by the American Academy of Indian Classical Music (AAICM) Photography, Cover Art and Design by Tina Psoinos 2 NI 6340 NI 6340 11 at Carnegie Hall, the Rubin Museum of Art and Raga Music Circle in New York, MITHAS in Boston, A True Master of Khayal; Recollections of a Disciple Raga Samay Festival in Philadelphia and many other venues. His awards are many, but include the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar by the Sangeet Natak Aka- In 1999 I was invited to meet Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, or Khan Sahib as we respectfully call him, and to demi, New Delhi, 2015 and the Gandharva Award by the Hindusthan Art & Music Society, Kolkata, accompany him on tanpura at an Indian music festival in New Jersey. -

Ailkura Atiga Atigahara Agratalasaficara Agrapluta Aficita

GLOSSARY OF SELECTED TECHNICAL TERMS A ailkura pantomiming through gestures atiga major limb, feature; a feature of degIllisya (q.v.) atigahara sequence of dance units; a feature of degillisya (q.v.) agratalasaficara a foot movement agrapluta a degI (q.v.) can (q.v.) aficita a neck movement; an arm movement; a foot movement; a karlll]a (q.v.); an utplutikarafia (q.v.) aficitabhramarI a whirling movement afijana a hand gesture a<;l~ a tlila (q.v.) a<;l<;litli a bhiimican (q.v.) a<;l~talaJl!1Ya a bandha (q.v.) dance adrutlilanrtya same as above anatiga a feature of degIllisya (q.v.) anibaddha loosely constructed in comparison to nibaddha (q.v.)(as applied to a song) anibandha freer composition in comparison to rigidly structured (as applied to a dance) anibandhanrtta a pure dance with scope for improvisation anibandhanrtya a mimetic dance with scope for improvisation anIld a feature of degIllisya (q.v.) anurnlina a feature of degillisya (q.v.) antarlilaga an utplutikarar:ta (q.v.) apasara exit; dance interludes in a play 261 262 GLOSSARY abbinaya acting, mimingj a feature of degiIasya (q.v.) ardhakuiicita a degi~\1ava (q.v.) ardhanikunaka a karatta or dance unit ardhacandra a single-hand gesture ardhasiici a karatta or dance unit aIarnkaragastra the manual on poetics alapallava a single-hand gesture alapadma a single-hand gesture avammasandhi a technical feature of drama avahittha a margasthina or a standing posture of traditional variety uvakrinta a margasthina or a standing posture of traditional variety alaga a leaping movement alita -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

DEFAULTER PART-A.Xlsx

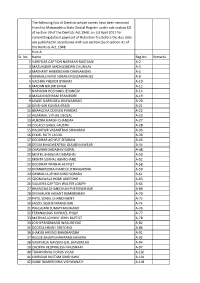

The following lists of Dentists whose names have been removed from the Maharashtra State Dental Register under sub-section (2) of section 39 of the Dentists Act,1948, on 1st April 2017 for committing default payment of Retention fee before the due date are published in accordance with sub section (5) of section 41 of the Dentists Act, 1948. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 VARIFDAR CAPTION NARIMAN RUSTAMJI A-2 2 MAZUMDAR MADHUSNDAN CHUNILAL A-3 3 MAEHANT HARIKRISHAN DHANAMDAS A-5 4 GINWALS MINO SORABJI NUSSAWANJEE A-9 5 VACHHA PHEROX BYRAMJI A-10 6 MADAN BALBIR SINGH A-12 7 NARIMAN HOSHANG JEHANGIV A-14 8 MASANI BEHRAM FRAMRORE A-19 9 JAWLE NARENDEA BHAWANRAO A-20 10 DINSHAW KAVINA ERAEH A-21 11 BHARUCHA COOVER PHIRORE A-22 12 AGARWAL VITHAL DEOLAL A-23 13 AURORA HARISH CHANDAR A-27 14 COLACO ISABEL FAUSTIN A-28 15 HALDIPWR VASANTRAO SHAMRAO A-33 16 EEKIEL RUTH JACOB A-39 17 DEODHAR ACHYUT SITARAM A-43 18 DESIAI BHAGWENTRAI GULABSHAWEAR A-44 19 CHAVHAN SADASHIV GOPAL A-48 20 MISTRI JEHANGIR DADABHAI A-50 21 MEHTA SUKHAL ABHECHAND A-52 22 DEODHAR PRABHA ACHYUT A-58 23 DHANBHOORA MANECK JEHANGIRSHA A-59 24 GINWALLA JEHMI MINO SORABJI A-61 25 SOONAWALA HOMI ARDESHIR A-63 26 SIGUEIRA CAPTION WALTER JOSEPH A-65 27 BHANICHA DHANJISHAH PHERIZWSHAW A-66 28 DESHMUKH VASANT RAMKRISHAN A-70 29 PATIL SONAL CHANDHAKNT A-72 30 JAGOS JASSI BYARANSHAW A-74 31 PAHLAJANI SUMATI MUKHAND A-76 32 FERANANDAS RUPHAEL PHILIP A-77 33 MATHIAS JOHNNY JOHN BAPTIST A-78 34 JOSHI PANDMANG WASUDEVAO A-82 35 DCOSTA HENNY SERTORIO A-86 36 JHAKUR ARVIND BHAKHANDRA -

University of Mumbai Department of Music Sample of MCQ Question Paper for Students M.Mus Part 2 Paper -V Course Name – Music

University of Mumbai Department of Music Sample of MCQ Question Paper for Students M.mus part 2 paper -V Course Name – Music Education Paper/Subject Code_________ Student’s Seat No._____ Instrructions; 1. All the Questions are Compulsory Total Marks – 50 2. All Questions Carry Equal Marks 1. Name the artist from Kirana Gharana among the following a. Sangmeshwar Gurav b. Mallikarjun Mansoor c. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit d. Faiyyaz Khan 2. Name the student of Ustad Allauddin Khan a. Ust. Aliakbar Khan b. Kishore Kumar c. Gayatri Chitre d. MAnik Varma 3. Name disciple of Ust. Alladiya Khan among the following a. Kesarbai b. Hirabai c. Begam Akhtar d. Parveen Sultana 4. Where the Indira Kala Vishwavidyalay is Located? a. Pune b. Mumbai c. Khairagadh d. Nagpur 5. Among following who is awarded with Padmavibhushan? a. Pt. Rakesh Chaurasia b. Pt. Jasraj c. Pt. Mukund Lath d. Sumitra Guha 6. Who was the Guru of Kumar Gandharva? a. Saraswati Rane b. B.R. Deodhar c. Kagalkar buwa d. Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale 7. Who had written book on Aesthetics of Indian Music? a. Sudheer Nayak b. Manjiri Sinha c. Rama Deodhar d. Ashok D. Ranade 8. Among the following which is a performing art? a. Natya b. Pottery c. Poetry d. Sculpture 9. Who was titled as Swarbhaskar ? a. Prabhakar Karekar b. Vinay Mishra c. Rajan Sajan Mishra d. Bhimsen Joshi 10. Who was the only direct disciple of Kesarbai Kerkar? a. Dhondutai Kulkarni b. Parmeshwar Hegade c. Pahadi Sanyal d. Jaimala Shiledar 11. Name the famous stage actor-singer a. Saleel Choudhari b. -

The Age Before Vinyl 7/4/20, 10:54 AM

The age before vinyl 7/4/20, 10:54 AM New e-paper Sign in Explore Saturday, 4 July 2020 Home Home >mint-lounge >features >The age before vinyl Latest Trending My Reads Pivot Or Perish Market Dashboard India-China Face-Off The Future Of Covid Tracker Lounge The Wonder That Was The Cylinder: By A.N. Sharma and Anukriti A. Sharma, Coronavirus Spenta Multimedia, 300 pages, Rs6,000 (including the DVD). India2Global Emerging Tech Conclave The age before vinyl 3 min read . 25 Oct 2014 Narendra Kusnur A tome on cylinder recordings by Gauhar Jan, Rabindranath Tagore and others Topics The Wonder That Was The Cylinder Vinyl records AN Sharma and Anukriti A Sharma Music Books It was another era, another technology. Before vinyl records ruled the scene in the early 20th century, the music industry was dominated by wax cylinders. The voices of some of India’s most reputed artistes were recorded on these hollow rolls; sadly, many of them have been lost. In their book, The Wonder That Was The Cylinder, A.N. Sharma and his daughter Anukriti present a detailed thesis on this fascinating subject. Aiding them in the research is their collection of rare cylinders, which they found lying with scrap dealers. Included are recordings of classical doyens Ustad https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/7EOnGuNasdjbQfQU9IckrK/The-age-before-vinyl.html Page 1 of 14 The age before vinyl 7/4/20, 10:54 AM Alladiya Khan and Pandit Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, Marathi music legends Bhaurao Kolhatkar, Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale and Balgandharva, and the father of Indian cinema, Dadasaheb Phalke. -

ISSN 2454-8596 Mogubai Kurdikar

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mogubai Kurdikar - The Doyen of Jaipur Atrauli Dr. Gurinder H. Singh Associate Professor Department of Music Janki Devi Memorial College University of Delhi New Delhi 110060 V o l u m e 1 I s s u e 1 A u g u s t - 201 5 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT The music world before nineteen hundreds was predominantly male oriented, when the female performers were either court singers or entertainers. Though in the changing times there were several talented women who were making new identities as concert singers. The two ladies to make this major transition were Alladiya Khan‟s students Mogubai Kurdikar and Kesar Bai Kelkar who marked a shift from chamber singing and Marathi stage drama to concert stage of classical Hindustani music. Their success attributed enormously towards the phenomenal fame of their guru, Ustad Alladiya Khan whose extraordinary style gained prominence and reigned the music world in north India years after him. It came to be known as the Jaipur Atrauli Gayaki which made considerable impact particularly in Maharashtra. This article is a life sketch of the musical journey of Mogu Bai Kurdikar, her undeterred resolve ensuing her deep commitment through the many social struggles. The old phonograph records of Mogubai Kurdikar in Raags Sohni, Basanti Kedar,Yaman, Swani Kalyan exquisitely demonstrate the gayaki of Jaipur Atrauli The listener is awestruck by the concluding taan which traverses four avartanas in rupak taal in the Raag Nayaki Kanada, without a break for breath. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Books and Publications Author's Name Year A Guide to Musical Acoustics H. Lowery English Published by Dobson Books Ltd. London A Historical Study of Indian Music Pragnanananda, English Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Private Swami 1981 Ltd., 54 Rani Jhansi Road, New Delhi 110055 A Short historical survey of the Music of Pt. V. N. Bhatkhande English upper India. Tr. By 1985 Baroda, Indian Musicological Society Dr. Arun Kumar Sen A Text Book of Botany Dr. V. Singh English Rastogi Publication, Shivaji road, Meerut A Text Book of Sound R. L. Saihgal English S. Chand & co., Delhi, New Delhi, Jullundar, Lucknow, Bombay A Text Book of Sound D. R. Khanna & English Atma Ram and Sons, Kashmiri Gate, Delhi R. S. Bedi 1980 A Text Book of Sound M. N. Srinivasan English Himalaya Publishing House, Ramdoot Dr. 1991 Bhallerao Marg, Gorgaon, Bombay Acoustics Leo L. Beranek English McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. New York, 1954 Toronto, London, Acoustics for Music Students, Madras C. S. Ayyar English Published by C. S. Ayyar, 46, Edward Elliots 1959 Road, Madras - 4, (India) Acoustics of Buildings F. R. Watson English New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1948 London: Chapman & Hall. Ltd. Bibliography 419 Acoustics of Buildings including acoustics of Watson Floyd Rowe English auditoriums and sound proofing of room 1948 Acoustics of Music Wilmer T. English New York, Prentice-hall, Inc., 70,5th Avenue Bartholomew 1950 Acoustics Wave and Oscillations S. N. Sen English Willey Eastern Ltd. 4834/24, Ansari Road, 1990 Dariya Ganj, New Delhi -110002 Aine Akbari Abul Fazal ; English English Translated by Francis Gladwin, Tr.