The Naming of Strays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approximate Weight of Goods PARCL

PARCL Education center Approximate weight of goods When you make your offer to a shopper, you need to specify the shipping cost. Usually carrier’s shipping pricing depends on the weight of the items being shipped. We designed this table with approximate weight of various items to help you specify the shipping costs. You can use these numbers at your carrier’s website to calculate the shipping price for the particular destinations. MEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 70 - 100 Jacket 1000 - 1200 Sports shirt, T-shirt 220 - 300 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 UnderpantsShirt 70120 - -100 180 JacketWind-breaker 1000800 - -1200 1200 SportsBusiness shirt, suit T-shirt 2201200 - -300 1800 Coat,Autumn duster jacket 9001200 - -1500 1400 Sports suit 1000 - 1300 Winter jacket 1400 - 1800 Pants 600 - 700 Fur coat 3000 - 8000 Jeans 650 - 800 Hat 60 - 150 Shorts 250 - 350 Scarf 90 - 250 UnderpantsJersey 70450 - -100 600 JacketGloves 100080 - 140 - 1200 SportsHoodie shirt, T-shirt 220270 - 300400 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 WOMEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 15 - 30 Shorts 150 - 250 Bra 40 - 70 Skirt 200 - 300 Swimming suit 90 - 120 Sweater 300 - 400 Tube top 70 - 85 Hoodie 400 - 500 T-shirt 100 - 140 Jacket 230 - 400 Shirt 100 - 250 Coat 600 - 900 Dress 120 - 350 Wind-breaker 400 - 600 Evening dress 120 - 500 Autumn jacket 600 - 800 Wedding dress 800 - 2000 Winter jacket 800 - 1000 Business suit 800 - 950 Fur coat 3000 - 4000 Sports suit 650 - 750 Hat 60 - 120 Pants 300 - 400 Scarf 90 - 150 Leggings -

Tips for Senior Portraits

Class of 2017 …Tips for Senior Portrait Days … Senior Portrait Day is a reminder that twelve years of academic work and the high school experience is coming to a close. Often in the rush “just to get finished” with a task, we do not give the moment its proper due. Good portraits of any kind require the photographer and the subject to work together to achieve the desired look. With all the advancements in digital photography today along with the touch- up software available, the ability to create a good portrait is now greatly enhanced. Technology alone, however, can never replace the human subject and thus, it is important to be prepared for your senior portrait day to ensure good results. Come prepared with a good attitude and ENJOY the process. Do not let minor stresses and concerns spoil the day. A relaxed, happy demeanor comes through in a photo and embracing and enjoying the process will aid in helping you look your best. The photo stations will have a tablet so you can view the portraits as taken if desired. This will help yo u get yo ur best lo o k the first sessio n. Portrait Purchase Purchase of portraits is o ptio nal. Pro o fs will be emailed to yo u fo r viewing, and o rder fo rms will be available o nline and at the school office. Clothing Ladies make sure you bring a tank or tube top / strapless bra to wear under the formal drape. Guys need to bring or wear a white undershirt to wear under the white dress shirt for both formal and cap and gown photos. -

Exploring Queer Expressions in Mens Underwear Through Post Internet Aesthetic As Vaporwave

Mens underwear :Exploring queer expressions in mens underwear through post internet aesthetic as Vaporwave. Master in fashion design Mario Eurenius 2018.6.09. 1. Abstract This work explores norms of dress design by the use of post internet aesthetics in mens underwear. The exploration of underwear is based on methods formed to create a wider concept of how mens underwear could look like regarding shape, color, material and details. Explorations of stereotypical and significant elements of underwear such as graphics and logotypes has been reworked to create a graphical identity bound to a brand. This is made to contextualize the work aiming to present new options and variety in mens underwear rather than stating examples using symbols or stereotypic elements. In the making of the examples for this work the process goes front and back from digital to physical using different media to create compositions of color, graphic designs and outlines using transfer printer, digital print, and laser cutting machine. Key words: Mens underwear, graphic, colour, norm, identity, post internet, laser cut. P: P: 2 Introduction to the field 3 Method 15 What is underwear? 39 Shape, Rough draping Historical perspective 17 Male underwear and nudity 41 From un-dressed to dressed 18 Graphics in fashion and textiles 42 Illustrator sketching 19 Differencesin type and categories of mensunderwear 43 shape grapich design 2,1 Background 3.1 Developement 45 collection of pictures 49 Colour 20 Vaporwave 50 Rough draping Japanese culture 21 Mucis 55 Rough draping 2 22 -

2000 Proceedings Cincinnati, OH

Cincinnati, OH USA 2000 Proceedings DOGWOOD IN GREEN AND GOLD Tammy Abbey Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA 98926 The purpose in creating this piece is to design an elegant garment through the combination of two very different techniques, metalsmithing and sewing. This design was inspired by extensive study in both metalworking and sewing and by blooming dogwood. The garment can be described as a dark green, fully lined dress in a polyester crepe satin. It is designed with princess lines and a gold charmeuse godet in the back. The dress is strapless and supported by the metal "lace." The "lace" is formed with brass blossoms and leaves that wrap the shoulders and overlap the front and the back of the dress. Brass blossoms also accent the godet. Construction began with an original pattern which was hand drafted. A muslin test garment was sewn, fitted and used to adjust the pattern. The main body of the dress was sewn and an invisible zipper was installed. A godet was sewn into the back. A polyester lining was sewn and then added to the dress. After the body of the dress was completed, the metal work began. Blossoms and leaves were cut from sheet brass. Then each was individually chased (hand shaped with the use of hammers and tools.) The pieces were given a copper patina (coloring) and brass brushed to a matte golden color. A dress form was used to assemble a base web of brass chain onto which the blossoms were sewn into place with thread and wire. Two blossoms and chain were added in the back to accent the godet and to contain it. -

The Paterek Manual

THE PATEREK MANUAL For Bicycle Framebuilders SUPPLEMEN TED VERSION Written by: Tim Paterek Photography by: Kelly Shields, Jens Gunelson, and Tim Paterek Illustrated by: Tim Paterek Photolabwork by: Jens Gunelson Published by: Kermesse Distributors Inc. 464 Central Avenue Unit #2, Horsham, PA 19044 216-672-0230 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book would not have been possible without help from the following people: Terry Osell Chris Kvale Roy Simonson Cecil Behringer Kelly Shields Jens Gunelson Dr. Josephine Paterek John Corbett Ginny Szalai Steve Flagg Special thanks must also go to: Dr. Hank Thomas Dr. James Collier Dr. Joseph Hesse John Temple Ron Storm Paul Speidel Laura Orbach Marty Erickson Mary Rankin Terry Doble Todd Moldenhauer Jay Arneson Susan Burch Harvey Probst Alan Cambronne Laurel Hedeen Martha Kennedy Bill Farrell Bill Lofgren Andy Bear The following companies were particularly help ful during the writing of this book: T.I. Sturmey-Archer of America Phil Wood Bicycle Research Binks Blackburn Design Dynabrade Handy Harmon Henry James New England Cycling Academy Strawberry Island Cycle Supply Ten Speed Drive Primo Consorizio G.P. Wilson Quality Bicycle Products Zeus Cyclery True Temper Cycle Products East side Quick Print Shimano Sales Corp. Santana Cycles Modern Machine and Engineering 3M AUTHORS FOREWORD There are many types of bicycle framebuilders and they can be easily categorized in the following way: 1. They offer custom geometrical specifications for each individual customer. 2. They offer any frame components the customer requests. i.e. tubing, lugs, dropouts, crown, shell, etc. 3. They offer custom finishing with a wide range of color choices. 4. They also offer the customer the option of building up a complete bike with any gruppo the customer wants. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

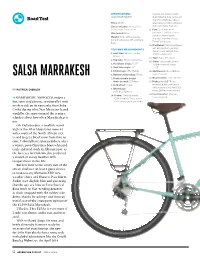

Salsa Marrakesh

SPECIFICATIONS mounts; disc brake mounts; SALSA MARRAKESH down tube/top tube guides and Road Test stops for shift/brake cables; Price: $1,599 spare spokes holder; kickstand Sizes available: 50cm, 52cm, plate; Alternator dropouts 54cm, 55cm, 57cm, 60cm 11. Fork: Steel Marrakesh Size tested: 55cm unicrown. 1 1/8-inch steerer, stainless double-eyelet Weight: 32 lb. (without pedals, dropouts, low-rider bosses, but with Alternator 135 Low Deck Three-Pack bosses Rack) 12. Handlebar: Salsa Cowchipper, 420 mm (center to center), TEST BIKE MEASUREMENTS 96mm reach, 116mm drop, 1. Seat tube: 560mm (center 31.8mm clamp area to top) 13. Tape: Salsa Gel, brown 2. Top tube: 550mm (effective) 14. Stem: Salsa Guide, 80mm, 3. Head tube angle: 70.75° 31.8mm four-bolt clamp, 4. Seat tube angle: 73° +/- 15° 5. Chainstays: 455-472mm 15. Shift levers: Microshift bar- SALSA MARRAKESH 6. Bottom bracket drop: 77mm cons, 9-speed 7. Crank spindle height 16. Brake levers: Tektro RL340 above ground: 279.4mm 17. Brakes: Avid BB7 Road 8. Fork offset: 55mm mechanical discs with inline cable adjusters and Avid G2CS 9. Wheelbase: BY PATRICK O'GRADY rotors, 160mm front and rear 1054.9-1071.9mm 18. Front derailer: Shimano 10. Frame: Cobra Kai butted Deore, 9-speed ➺MARRAKESH, MOROCCO, enjoys a 4130 chromoly. Three sets of hot, semi-arid climate, so naturally I took bottle bosses; rack and fender my first ride on its namesake from Salsa Cycles during what New Mexicans feared would be the snowstorm of the century, which is about how often Marrakesh gets one. -

Queers on What We Wear

QUEERS ON WHAT WE WEAR MEGAN VOLPERT etaliapress.com Little Rock, Arkansas 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Megan Volpert Text and images by contributors, except as otherwise noted Cover design by Amy Ashford, ashford-design-studio.com ISBN: 978-1-944528-06-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932179 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of reviews. Contact publisher for permission under any circum-stances aside from book reviews. Et Alia Press titles are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity directly from the Press. For details, contact [email protected] or the address below. Published in the United States of America by: Et Alia Press PO Box 7948 Little Rock, AR 72217 [email protected] etaliapress.com door and step into a more fabulous future. fabulous door andstepintoamore May the fierceness of these contributors help us all to open the closet wash. the in shrink not clothes our May emergencies. like feel not bodies valid. May our feelings about the color pink are Our conflicting is real. Our boots have blood on them. Our struggle to find the perfect shirt This bookisdedicatedtoqueersinclosetseverywhere. sartorial: relating totailoring,clothes,orstyleofdress sartorial: relating satori: suddenenlightenment CLOSET CASES / AIRIN YUNG SUMMER OUTING my mom told me to wear more pink more jewelry: jīn; to pray more to jesus m o r e— so i sent her this photo; [Read 3:16pm] [Read Yesterday 3:16pm] [Read 07/04/18 3:16pm] -- pink, jīn, jesus, jender i am m o r e of everything and enough for me. -

Le Livre 1 Milky Ange Unofficial Fanbook

leby milkylivre ange 6 styles of maid dresses for every theme, situation, and occasion Milky Ange Unofficial Fanbook Volume 1 for ALL MAID LOVERS Classic Style Maid Claris Cafe Style Maid Kirsten Y AN • MILK GE • Romantic Style Maid Renee Classic Style Maid Rita • U • NO K FFIC BOO IAL FAN Tyrolean Style Maid Fenella Romantic Style Maid Florianne Claris Long by milky ange Outfit Design © 2019 Kijishiro Corp Character Illustration © 2019 Shiho Sakura milky ange 100% Original Maid Dress & Lolita Fashion 4 | VOLUME 1 5 CLARIS LONG CLASSIC STYLE MAID DRESS BLACK | ICY BLUE A classical style maid dress with shoulder frill and yoke. Shoulder yoke features pin tuck and lace. Lace details are also added to the stand collar and cuffs to further emphasize the classical look. Comes with pinned deep red bow tie with tulle lace. 6 | VOLUME 1 100% ORIGINAL MAID DRESS & LOLITA FASHION 078.778.4169 WWW.MILKY-ANGE.COM 7 CLASSIC STYLE MAID CLARIS LONG Black AC-0265 (S) ¥28,080 AC-0266 (ML) ¥30,240 AC-0267 (XL) ¥32,400 HEADBAND 04 AC-0052 ¥3,780 CAPE VIVI AC-0400 (S-ML) ¥19,440 AC-0401 (XL-XXL) ¥21,600 LACE TRIMMED PANNIER WITH 3 STEEL HOOPS AC-0156 ¥14,040 DRAWER TINA AL-0223 ¥10,800 LEGWEAR 05 (White lace top thigh high stockings) AC-0353 ¥4,320 8 | VOLUME 1 100% ORIGINAL MAID DRESS & LOLITA FASHION 078.778.4169 WWW.MILKY-ANGE.COM 9 CLARIS LONG CLASSIC STYLE MAID DRESS BLACK | ICY BLUE Set Includes • Maid dress, apron, and removable bow tie. -

Tolar Junior High and High School Dress Code

Tolar Junior High and High School Dress Code Personal appearance is important. Modesty will be the dominant feature in all clothing. Behavior, attitude and community standards take precedence over individual clothing and hairstyle. The campus principal is the final authority concerning the propriety of clothes, hairstyle, and jewelry. Clothing • Clothes must be appropriately sized (not excessively tight); • No cleavage-revealing tops; • Exposure of midriffs (front or back) and low cut shirts are prohibited; • No holes in clothing that reveal skin in shirts, or pants above the knees (patches must cover all holes); • Shirts must not be backless or completely shoulder-less (partial shoulder is permitted); • Female students may wear ͞sheer tops͟ provided that the clothing underneath is in accordance with school dress code. Example: No exposed spaghetti straps, bra, midriffs, tube top; • All shorts must be no shorter than 4 inches above the top of the knee cap. No running shorts allowed. Examples: Nike wind shorts and similar loose fitting shorts; • Tights/athletic pants/yoga pants/jeggings must be accompanied by a shirt or dress that adequately covers the entire bottom; • No sagging or oversized clothing; • No pajamas; • Visible underwear, spaghetti strap tanktops, and muscle shirts will not be permitted; • Sleeveless shirts must have a collar or t-shirt type collar and be hemmed around the sleeves. Straps on sleeveless shirts must be at least 1 inch.; • Articles of clothing advertising (or mimicking advertising of) alcoholic beverages, tobacco products, depicting killing or violence or those with obscene or questionable printing or signs on them will not be permitted. Hair • Beards, goatees, and mustaches are not permitted. -

Student Information

TABLE OF CONTENTS EVENT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................1 CHAPERONE INFORMATION ......................................................................................... 1-2 Chaperone Wristband, Chaperone Lounges, Chaperone Breakfast, Universal ExpressSM Unlimited CHAPERONE INSTRUCTIONS ...........................................................................................2 TRANSPORTATION, DRIVING DIRECTIONS AND BUS DRIVER INFORMATION .............................................................................................3 ARRIVAL NOTES ........................................................................................................... 4-5 DEPARTURE NOTES .........................................................................................................6 STUDENT INFORMATION ..................................................................................................7 DRESS CODE ....................................................................................................................8 UniversalOrlando.com/GradBash • 1-800-YOUTH15 EVENT OVERVIEW • CHAPERONE INFORMATION EVENT OVERVIEW Universal’s Grad Bash ‘14 is a separately ticketed, private event for graduating high school seniors and their chaperones. The one-night event encompasses both Universal Orlando® Resort theme parks and features live concerts and street entertainment, as well as the parks’ rides and attractions. CHAPERONE information As a chaperone, you play -

Mumford Dress Code Quick Reference ITEMS NOT ALLOWED! Item NOT ALLOWED • No Racer Backs, Spaghetti Straps, Halter Tops, Strapless, And/Or Tube Tops

Mumford Dress Code Quick Reference ITEMS NOT ALLOWED! Item NOT ALLOWED • No Racer backs, Spaghetti straps, Halter tops, Strapless, and/or tube tops. • No Low plunging neckline, see through, cropped shirts that expose the stomach and back Girls: when bending, stretching, etc. Shirts • No Shirts exposing too much skin, the shoulder blades, or undergarments. • No see through shirts without proper undershirts. Boys: • No Undershirts, muscle shirts, or shirts with sleeves cut off worn as main clothing item. Shirts • No Headbands or bandos. Girls & • No Shirts that contain graphics, words, or images that are inappropriate including: Boys Shirts drugs, gangs, alcohol, violence, sexual connotations, etc. • No Items shorter than 6 inches above back of middle of the knee or shortest part of the skirt/dress AND are less than 4 inches from the bottom of the buttocks. Skirts/ Dresses • No Dresses/Skirts that are excessively snug fitting. • No see through skirts/dresses without proper undergarments, of the proper length. • No Items shorter than 6 inches above back of middle of the knee or shortest part of the shorts AND are less than 4 inches from the bottom of the buttocks. Shorts • No Cut Off Shorts; all shorts must be stitched or cuffed. • No Biker or spandex shorts. • No Baggy, oversized, saggy pants. • No Yoga or leggings as primary clothing. If worn they must be paired with a shirt/dress that is no shorter than 6 inches above back of the middle of the knee or shortest part of the shirt/dress AND is at least 4 inches from bottom of the buttocks.