“Crazy Horse with Us”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plains Indians

Your Name Keyboarding II xx Period Mr. Behling Current Date Plains Indians The American Plains Indians are among the best known of all Native Americans. These Indians played a significant role in shaping the history of the West. Some of the more noteworthy Plains Indians were Big Foot, Black Kettle, Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Spotted Tail. Big Foot Big Foot (?1825-1890) was also known as Spotted Elk. Born in the northern Great Plains, he eventually became a Minneconjou Teton Sioux chief. He was part of a tribal delegation that traveled to Washington, D. C., and worked to establish schools throughout the Sioux Territory. He was one of those massacred at Wounded Knee in December 1890 (Bowman, 1995, 63). Black Kettle Black Kettle (?1803-1868) was born near the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota. He was recognized as a Southern Cheyenne peace chief for his efforts to bring peace to the region. However, his attempts at accommodation were not successful, and his band was massacred at Sand Creek in 1864. Even though he continued to seek peace, he was killed with the remainder of his tribe in the Washita Valley of Oklahoma in 1868 (Bowman, 1995, 67). Crazy Horse Crazy Horse (?1842-1877) was also born near the Black Hills. His father was a medicine man; his mother was the sister of Spotted Tail. He was recognized as a skilled hunter and fighter. Crazy Horse believed he was immune from battle injury and took part in all the major Sioux battles to protect the Black Hills against white intrusion. -

Young Man Afraid of His Horses: the Reservation Years

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Young Man Afraid of His Horses: The Reservation Years Full Citation: Joseph Agonito, “Young Man Afraid of His Horses: The Reservation Years,” Nebraska History 79 (1998): 116-132. URL of Article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1998-Young_Man.pdf Date: 1/20/2010 Article Summary: Young Man Afraid of His Horses played an important role in the Lakota peoples’ struggle to maintain their traditional way of life. After the death of Crazy Horse, the Oglalas were trapped on the reservation , surrounded by a growing, dominant, white man’s world. Young Man Afraid sought ways for his people to adapt peacefully to the changing world of the reservation rather than trying to restore the grandeur of the old life through obstructionist politics. Cataloging Information: Names: Man Afraid of His Horses; Red Cloud; J J Saville; Man Who Owns a Sword; Emmett Crawford; -

Teacher’S Guide Teacher’S Guide Little Bighorn National Monument

LITTLE BIGHORN NATIONAL MONUMENT TEACHER’S GUIDE TEACHER’S GUIDE LITTLE BIGHORN NATIONAL MONUMENT INTRODUCTION The purpose of this Teacher’s Guide is to provide teachers grades K-12 information and activities concerning Plains Indian Life-ways, the events surrounding the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the Personalities involved and the Impact of the Battle. The information provided can be modified to fit most ages. Unit One: PERSONALITIES Unit Two: PLAINS INDIAN LIFE-WAYS Unit Three: CLASH OF CULTURES Unit Four: THE CAMPAIGN OF 1876 Unit Five: BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIGHORN Unit Six: IMPACT OF THE BATTLE In 1879 the land where The Battle of the Little Bighorn occurred was designated Custer Battlefield National Cemetery in order to protect the bodies of the men buried on the field of battle. With this designation, the land fell under the control of the United States War Department. It would remain under their control until 1940, when the land was turned over to the National Park Service. Custer Battlefield National Monument was established by Congress in 1946. The name was changed to Little Bighorn National Monument in 1991. This area was once the homeland of the Crow Indians who by the 1870s had been displaced by the Lakota and Cheyenne. The park consists of 765 acres on the east boundary of the Little Bighorn River: the larger north- ern section is known as Custer Battlefield, the smaller Reno-Benteen Battlefield is located on the bluffs over-looking the river five miles to the south. The park lies within the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana, one mile east of I-90. -

Review Essay: Custer, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and the Little Bighorn

REVIEW ESSAY Bloodshed at Little Bighorn: Sitting Bull, Custer, and the Destinies of Nations. By Tim Lehman. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. 219 pp. Maps, illustrations, notes, bibliogra- phy, index. $19.95 paper. The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. By Nathaniel Philbrick. New York: Viking, 2010. xxii + 466 pp. Maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index. $30.00 cloth, $18.00 paper. Custer: Lessons in Leadership. By Duane Schultz. Foreword by General Wesley K. Clark. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. x + 206 pp. Photographs, notes, bibliography, index. $14.00 paper. The Killing of Crazy Horse. By Thomas Powers. New York: Knopf, 2010. xx + 568 pp. Maps, illustra- tions, photographs, notes, bibliography, index. $30.00 cloth, $17.00 paper. CUSTER, CRAZY HORSE, SITTING BULL, AND THE LITTLE BIGHORN In the summer of 1876, the United States some Cheyennes, and a handful of Arapahos. government launched the Great Sioux War, The resulting Battle of the Little Bighorn left a sharp instrument intended to force the last Custer and 267 soldiers, Crow scouts, and civil- nonagency Lakotas onto reservations. In doing ians dead, scattered in small groups and lonely so, it precipitated a series of events that proved singletons across the countryside—all but disastrous for its forces in the short run and fifty-eight of them in his immediate command, calamitous for the Lakotas in the much longer which was annihilated. With half the regiment scheme of things. killed or wounded, the Battle of the Little On June 17, Lakotas and Cheyennes crippled Bighorn ranked as the worst defeat inflicted General George Crook’s 1,300-man force at the on the army during the Plains Indian Wars. -

Cultural Play at the Crazy Horse Colossus: Narrative

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication Summer 7-14-2010 Cultural Play at the Crazy Horse Colossus: Narrative Thomas M. Cornwell Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cornwell, Thomas M., "Cultural Play at the Crazy Horse Colossus: Narrative." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURAL PLAY AT THE CRAZY HORSE COLOSSUS: NARRATIVE RATIONALITY AND THE CRAZY HORSE MEMORIAL ORIENTATION FILM by THOMAS M. CORNWELL Under the Direction of Dr. Mary Stuckey ABSTRACT This thesis explores the Crazy Horse Memorial orientation film and its rhetorical claim to represent Lakota values in the rhetorically contested Black Hills of South Dakota. Walter Fisher‟s concept of narrative rationality is used to analyze the informal logic of the memorial film narrative. The Crazy Horse Memorial is seen as a response to Mt. Rushmore‟s colonialist legacy. Analysis shows that the Crazy Horse Memorial actually has much in common with Rushmore‟s legacy of Euro-American colonialism. This thesis discusses the effects of this redefinition of Lakota cultural values on the rhetorical sphere of the contested Black Hills. INDEX WORDS: Narrative rationality, American Indians, Crazy Horse Memorial, Black Hills, Lakota, Mount Rushmore, Colossal art, Orientation film CULTURAL PLAY AT THE CRAZY HORSE COLOSSUS: NARRATIVE RATIONALITY AND THE CRAZY HORSE MEMORIAL ORIENTATION FILM by THOMAS M. -

Figure Descriptions of the Wilkins-Black Road Ledger

Figure Descriptions of the Wilkins-Black Road Ledger Figure 1. Sitting Bull (Tatanka Iyotake), Hunkpapa Lakota chief photographed at Bismarck, Dakota Territory, by Orlando Scott Goff, July 31, 1881, shortly after he had returned from a four-year exile in Canada. Denver Public Library, Neg. No. X-31935. Figure 2. (Lower) Sitting Bull while a prisoner-of-war at Fort Randall, D.T. Drawing by Rudolf Cronau, 25 October 1881. Lamplin-Wunderlich Gallery, New York City. (Upper) A drawing by Sitting Bull while he was at Fort Randall, 1882 (National Anthropological Archives, Cat. No. INV 08589900). His horses are heavy-bodied; and his human hands are drawn with the four fingers and thumb extended. These details are radically different than the figures in the Wilkins Ledger, demon- strating that Sitting Bull could not have been the artist. Figure 3. Historical marker at the abandoned site of La Grace, Dakota Territory, testifying to the sometime presence there of Sitting Bull, as a visitor. Charles A. Wilkins was a Justice of the Peace in Campbell County, in which La Grace was located. He told his family that the ledger of drawings was a gift to him from Sitting Bull, after he allowed the chief to sleep overnight as a guest in the jail at La Grace, when no other accomodations were available. Figure 4. “Sitting Bull Indians Crossing the Yellowstone River, near Fort Keogh, to Surrender to General Miles.” Engraving from Frank Leslie's Illustrated News, July 31, 1880. Denver Public Library, Neg. No. X-33625. Among the exiles with Sitting Bull in Canada were several hundred Oglala, led by Chief Big Road. -

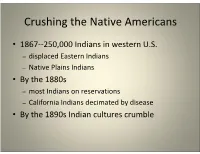

Crushing the Native Americans

Crushing the Native Americans • 1867--250,000 Indians in western U.S. – displaced Eastern Indians – Native Plains Indians • By the 1880s – most Indians on reservations – California Indians decimated by disease • By the 1890s Indian cultures crumble Essential Questions 1) What motivated Americans from the east to move westward? 2) How did American expansion westward affect the American Indians? 3) How was American “identity” forged through westward expansion? Which picture best represents America? What affects our perception of American identity? Life of the Plains Indians: Political Organization • Plains Indians nomadic, hunt buffalo – skilled horsemen – tribes develop warrior class – wars limited to skirmishes, "counting coups" • Tribal bands governed by chief and council • Loose organization confounds federal policy Life of the Plains Indians: Social Organization • Sexual division of labor – men hunt, trade, supervise ceremonial activities, clear ground for planting – women responsible for child rearing, art, camp work, gardening, food preparation • Equal gender status common – kinship often matrilineal – women often manage family property Misconceptions / Truths of Native Americans Misconceptions Truths • Not all speak the same • Most did believe land belonged language or have the same to no one (no private property) traditions • Reservation lands were • Not all live on reservations continually taken away by the • Tribes were not always government unified • Many relied on hunting as a • Most tribes were not hostile way of life (buffalo) • Most tribes put a larger stake on honor rather than wealth Culture of White Settlers • Most do believe in private property • A strong emphasis on material wealth (money) • Few rely on hunting as a way of life; most rely on farming • Many speak the same language and have a similar culture What is important about the culture of white settlers in comparison to the culture of the American Indians? What does it mean to be civilized? “We did not ask you white men to come here. -

Remarks by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy Before the National

~tpartmtnt ll~ ~ustitt REMARKS By ATroRNEY GENERAL ROBERT F. KENNEDY Before The NATIONAL CONGBESS OF AMH:RICAN INDIANS Grand Pacific Hotel Bismarck, North Dakota September 13, 1963 It is a tragic irony that the American Indian has for so long been denied a full share of freedom -- full citizenship in the greatest free country in the world. And the irony is compounded when we realize how great the influence of Indian culture has been in shaping our national character. The earliest white settlers in this country were quick to adopt Indian ways of dealing with the harsh elements of their new world; they must certainly have learned more from the Indians than the-Indians from them. The men who framed our Constitution are said to have drawn much of their inspiration from tribal practices of the Iroquois League -- the concept of a Union of sovereign states, for example, and the principle of .Government by consent of the governed, The nobility and valor of the great warrior chiefs -- men like Wabasha, Pontiac, Tecumseh and Black Ha~k; like Crazy Horse, Sitting BUll, American Horse, Cochise, and Joseph -- will always hold an honored place in our his tory. Nearly half our states and many hundreds of our cities and towns bear Indian names; numberless Indian words and phrases have become a part of the American language and the American philosophy. And still the paradox exists. Alexis de Tocqueville, that nineteenth century French traveler who seemed to know so much more about America than the Americans knew about themselves, was outspoken in his admiration of the Indian race -- and in his disapproval of their treatment. -

Free Ebook Library Victorio: Apache Warrior and Chief (The

Free Ebook Library Victorio: Apache Warrior And Chief (The Oklahoma Western Biographies) A steadfast champion of his people during the wars with encroaching Anglo-Americans, the Apache chief Victorio deserves as much attention as his better-known contemporaries Cochise and Geronimo. In presenting the story of this nineteenth-century Warm Springs Apache warrior, Kathleen P. Chamberlain expands our understanding of Victorio’s role in the Apache wars and brings him into the center of events.Although there is little documentation of Victorio’s life outside military records, Chamberlain draws on ethnographic sources to surmise his childhood and adolescence and to depict traditional Warm Springs Apache social, religious, and economic life. Reconstructing Victorio’s life beyond the military conflicts that have since come to define him, she interprets his character and actions not only as whites viewed them but also as the logical outcome of his upbringing and worldview.Chamberlain’s Victorio is a pragmatic leader and a profoundly spiritual man. Caught in the absurdities of post–Civil War Indian policy, Victorio struggled with the glaring disconnect between the U.S. government’s vision for Indians and their own physical, psychological, and spiritual needs.Graced with historic photos of Victorio, other Apaches, and U.S. military leaders, this biography portrays Victorio as a leader who sought a peaceful homeland for his people in the face of wrongheaded decisions from Washington. It is the most nearly complete and balanced picture yet to emerge of a Native leader caught in the conflicts and compromises of the nineteenth-century Southwest. -

1868 Chief Red Cloud and General William Tecumseh Sherman Sign the Fort Laramie Treaty, Which Brings an End to War Along the Bozeman Trail

1868 Chief Red Cloud and General William Tecumseh Sherman sign the Fort Laramie Treaty, which brings an end to war along the Bozeman Trail. Under terms of the treaty, the United States agrees to abandon its forts along the Bozeman Trail and grant enormous parts of the Wyoming, Montana and Dakota Territories, including the Black Hills area, to the Lakota people as their exclusive territory. 1868 General Philip Sheridan sends Colonel George Armstrong Custer against the Cheyenne, with a plan to attack them during the winter when they are most vulnerable. Custer's troops locate a Cheyenne village on the Washita River in present-day Oklahoma. By a cruel coincidence, the village is home to Black Kettle and his people, the victims of the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Custer's cavalry attacks at dawn, killing more than 100 men, women and children, including Black Kettle. 1875 THE LAKOTA WAR A Senate commission meeting with Red Cloud and other Lakota chiefs to negotiate legal access for the miners rushing to the Black Hills offers to buy the region for $6 million. But the Lakota refuse to alter the terms of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, and declare they will protect their lands from intruders if the government won't. 1876 Federal authorities order the Lakota chiefs to report to their reservations by January 31. Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and others defiant of the American government refuse.General Philip Sheridan orders General George Crook, General Alfred Terry and Colonel John Gibbon to drive Sitting Bull and the other chiefs onto the reservation through a combined assault. -

JUDITH ST. GEORGE's NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY by Judith St

JUDITH ST. GEORGE'S NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY by Judith St. George INTRODUCTION Discussion and Reading Guide for Native American History Books by Judith St. George Several years ago I came upon the tragic history of the Sioux Indians while doing research for a book about Mount Rushmore. The Sioux were once the most powerful tribe in America. Today the Sioux Pine Ridge Reservation is among the nation's poorest communities. How could this happen? Researching and reading about the Sioux led me to write biographies of Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull. A third biography naturally followed. Sacagawea, the young Shoshone woman who accompanied Lewis and Clark to the Pacific, had been my childhood heroine. Writing all three biographies from the Indians' point of view gave me the opportunity to describe their customs and practices in depth. This Study Guide will help teachers broaden their students' understanding of Indian life, traditions, beliefs, and history. By raising pertinent questions, the Guide also will encourage discussion, as well as lead students on to further reading and discovery about our country's Native American heritage. About the Author Judith St. George was born and raised in Westfield, New Jersey. Following her graduation from Smith College, she married and lived for a year in the historic Longfellow House in Cambridge, Massachusetts, George Washington's headquarters during the American Revolution. She attributes much of her interest in history, about which she writes with authority and enthusiasm, to this experience. While writing more than twenty-five books, ranging from mysteries to histories, she has also taught workshops and run story hours and reading programs for children. -

Fort Robinson, Outpost on the Plains

Fort Robinson, Outpost on the Plains (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Roger T Grange Jr, “Fort Robinson, Outpost on the Plains,” Nebraska History 39 (1958): 191-240 Article Summary: Granger describes military activity at Fort Robinson during the Sioux Wars and includes details of garrison life in more peaceful times. Those stationed at the fort responded to the Cheyennes’ attempt to return from Indian Territory, the Cheyenne outbreak, and the Ghost Dance troubles. The fort was used for military purposes until after World War II. Note: A list of major buildings constructed at Fort Robinson 1874-1912 appears at the end of the article. Cataloging Information: Names: P H Sheridan, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, J J Saville, John W Dear, Red Cloud, Old Man Afraid of His Horses, Young Man Afraid of His Horses, Frank Appleton, J E Smith, Levi H Robinson, William Hobart Hare, Toussaint Kenssler, O C Marsh, Moses Milner (“California Joe”), Big Bat Pourier, Frank Grouard, Valentine T McGillycuddy, Ranald