The Ideal Woman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sword and Sorcery Jump by Worm Anon Have You Heard the Stories Jumper? Tales of Lands Where Man Was Young Even As the World

Sword and Sorcery Jump By Worm_Anon Have you heard the stories Jumper? Tales of lands where man was young even as the world was already old. Stories of Gods, demons, and stranger things. Legends wrought in blood, steel, and fire by men who strode the world to cleave their mark into the merciless passage of time. You shall be going to these ancient lands Jumper. From the barren stone and sand civilizations ever drag themselves forward from barbaric beginnings on the backs of warriors and kings. Thieves glide through shadows to plunder vast and forgotten vaults. Sorcerers reach beyond the veil into alien dimensions to seize power from eldritch beings. This is an age of myth and legend. Where the strength of a man’s arm, the sweat of his brow, and the roar of his heart is all it takes to seize whatever it is he may desire. A story of great passion and glory is yours for the taking. Here is 1000cp to wrest the beginning of your story from the curse of banality fate would condemn most of your kind to. Beyond this you must make your own way. I eagerly await just what story shall be wrought by your passing Jumper. Do not disappoint me. Location There are many storied locales that may serve as the beginning of your tale. Roll 1d8 to see where it is that you begin. You may pay 50cp to deny the whims of fate and choose for yourself. 1. The Kingdom in the Crescent: A city state that has laid claim to a long line of kings ever since a great warrior seized it’s fertile lands by strength of arms. -

On Defining the Category MONSTER

On defining the category MONSTER – using definitional features, narrative categories and Idealized Cognitive Models (ICM’s) Piet Swanepoel Department of Afrikaans & Theory of Literature (Unisa) This paper explores how the coherence between a lexical item which denotes a category and the lexical items that refer to individual members of the category can be expressed in explanatory dictionaries. A detailed analysis is provided of the relationship between the lexical item monster (which refers to a category) and the lexical items that refer to individual members of this category (e.g., Cyclops, dragon, mermaid, vampire, werewolf, Dracula, and zombie). More specifically, the goal of the paper is to determine whether the semantic explanation(s) for monster could function as a dictionary internal (as opposed to Fillmore’s (2003) external) cognitive frame for the other lexical items in the monster set. If not, the question is whether and how the field of monsterology could assist one in designing such a frame and what the content, structure and function of such a frame would be. In Section 2.1 the focus falls on current lexicographic practices and problems in defining the category monster and its members. The dictionary entries for monster and those of a number of its members in a selection of English explanatory dictionaries are surveyed to determine what cognitive models of the category monster underlie these definitions. In Section 2.2 the focus falls on the definitional features, ICM’S and narrative structures used to define the category of the monster in the field of monsterology and on the numerous meanings monsters may have as symbolic expressions (metaphors in particular). -

Monster of the Week Revised

Fate Gear , You get to decide what sort of fate is in store for you. Pick You can have protective gear worth 1-armour, if you want. how you found out about your fate on the reverse side of You have a special weapon you are destined to wield. this sheet. The Chosen Your Special Weapon Moves Design your weapon by choosing a form and three busi- Your birth was prophesied. You are the Chosen You get all of the basic moves, plus three Chosen moves. ness-end options (which are added to the base tags), and a material. For example, if you want a magic sword One, and with your abilities you can save the You get these two: world. If you fail, all will be destroyed. It all rests you could choose the following: handle + blade + long + B Destiny’s Plaything: At the beginning of each on you. Only you. magic. mystery, roll +Weird to see what is revealed about your immediate future. On a 10+, the Keeper will Form (choose 1): CHARM • Manipulate Someone reveal a useful detail about the coming mystery. On b staff (1-harm hand/close) a 7-9 you get a vague hint about it. On a miss, some- b haft (2-harm hand heavy) • Act Under Pressure thing bad is going to happen to you. b handle (1-harm hand balanced) b chain (1-harm hand area) COoL • Help Out B I’m Here For A Reason: There’s something you are destined to do. Work out the details with the Keeper, • Investigate a Mystery Business-end (choose 3 options): based on your fate. -

Boss Monster

Boss Monster is the fast-paced card game of strategic dungeon building! As a Boss Monster, your goal is to lure hapless adventurers into your dungeon and consume their souls. But beware! Your dungeon must be as deadly as it is enticing, or the puny heroes can actually survive long enough to wound you. More importantly, you have competition. Adventurers are a hot commodity, and other Boss Monsters are all trying to outdo you with more precious treasures and more nefarious traps. Are you a bad enough dude to become the ultimate Boss Monster? To play Boss Monster, you just need 2-4 players, the After setting up the game (see “Set Up” on p. 6), players cards included with this game, and enough space to participate in a series of turns. Each turn consists of five spread out your cards. phases. The first time you play, allow yourself at least 45 minutes. Beginning of Turn: Reveal Heroes (one per player), then each player draws a card from the Room Deck. Once players are familiar with the cards, a game will typically take 15-20 minutes. Build Phase: Each player may build one Room. Players take turns placing their room cards face down. At the end of the Build phase, newly built rooms are revealed. The goal of Boss Monster is to lure Heroes into your Bait Phase: Heroes move to the entrance of the dungeon and kill them. Heroes who die in your dungeon dungeon with the highest corresponding Treasure value. (No spells or abilities may be played.) are turned face down and count as “Souls.” Heroes who survive give you “Wounds.” Adventure Phase: Heroes travel through dungeons, and players acquire Souls or Wounds. -

Steampunk: Mary Shelleys Frankenstein PDF Book

STEAMPUNK: MARY SHELLEYS FRANKENSTEIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Zdenko Basic,Manuel Sumberac | 384 pages | 05 Aug 2012 | Running Press | 9780762444274 | English | Philadelphia, United States Steampunk: Mary Shelleys Frankenstein PDF Book Mary Wollstonecraft was an English writer who advocated for women's equality. When the brilliant but unorthodox scientist Dr. When Waldman dies, Victor steals his notes and tries Seminar paper from the year in the subject English Language and Literature Studies She also liked to daydream, escaping from her often challenging home life into her imagination. Runtime: min. Justine Gerard Horan Categories :. Lord Byron suggested that they all should try their hand at writing their own horror story. This struggle between a monster and its creator has been an enduring part of popular culture. Quotes Victor Frankenstein : You do speak! Clear your history. Running Press Book Publishers. Nominated for 1 Oscar. Top 50 Highest-Grossing s Horror Films. Home 1 Books 2. The Invisible Man by H. Metacritic Reviews. Sign In Don't have an account? External Reviews. Age Range: 12 - 17 Years. Shelley could often be found reading, sometimes by her mother's grave. William Blake was a 19th-century writer and artist who is regarded as a seminal figure of the Romantic Age. In , Mary began a relationship with poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her stepmother decided that her stepsister Jane later Claire should be sent away to school, but she saw no need to educate Shelley. Steampunk: Mary Shelleys Frankenstein Writer Rate This. When Waldman dies, Victor steals his notes and tries It was at this time that Mary Shelley began work on what would become her most famous novel, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. -

A Card Game for 2 to 4 Players by Néstor Romeral Andrés

A card game for 2 to 4 players by Néstor Romeral Andrés INTRODUCTION In Halloween , players play the role of dark lords recruiting minions across a graveyard. Whoever recruits the best army of Setup example for a 4-player game undead will win the game. From now on, players do the following on their turn, in order: MATERIAL 1. Optionally, you can inspect graves once (see below). This is what you need in order to play Halloween : 2. (Mandatory) Move your dark lord in a straight line - 80 counters (headstones) in 4 colours (20 each of horizontally or vertically as many spaces as you wish, red, blue, yellow, green). without leaving the graveyard and landing on a card not occupied by another dark lord (it can be occupied by a - 4 dark lords (red, blue, yellow, green) stone). If the card is facing down, turn it facing up and place a counter (headstone) of your colour on it (thus claiming the card). If the card was already facing up then do nothing. - A deck of 36 mini-cards with the following structure: o The back of the cards shows a closed grave. There are 4 colours of graves (9 each of white, gray, black, brown). o For each grave colour, there are these fronts: ° 2 zombies (4 points each) ° 2 skeletons (3 points each) ° 2 ghosts (2 points each) Example: The red dark lord moves 2 spaces and lands onto an ° 3 will-o'-the-wisp (1 point each) unrevealed card. Then flips it facing up. It’s a skeleton! He finally claims the card by placing a red headstone on it. -

Setup Starting and Finishing the Game

The Gears monsters are Clocktopus, Flying Skull, Gearhead, More Munchkin! Golden Golem, The Gyroscopic Pharaoh, Infernal Engine, Example of Combat, Death Land Leviathan, Mousetrap, If you die, you lose all your stuff. You keep your Class(es) and Visit munchkin.game for news, errata, updates, Q&A, Robot Queen Victoria, Runaway With Numbers and Everything Level (and any Curses that were affecting you when you died) – your and much more. To discuss Munchkin with our staff and Velocipede, Steamhunk, Tele- your fellow munchkins, visit our forums at forums.sjgames. Jules is a 6th-Level Explorer wearing the Aeronautic new character will look just like your old one. If you have Super Visual Reception Apparatus, com/munchkin. Check out munchkin.game/gameplay/ Armor (which gives him a +4 to his combat strength) Munchkin, keep that as well. Once you have died, you don’t have to Theo D’Olite, and Titan of Industry. resources for reference cards, playmats, and dozens of links. and carrying the Cane-Sword, the Cane-Pistol, and the Run Away from any remaining monsters. The Gears items are Aeronautic Cane-Gatling Gun (for a total +9 bonus). He kicks open Use the #PlayMunchkin hashtag on social media to get our Armor, Automatic Monocle, the door and finds the Gyroscopic Pharaoh, a Level 14 attention! Canesaw, Cogwheel Cuirass, monster. Jules is at a 19, the Pharaoh is only at a 14, so Twitter. Our Twitter feed often has Munchkin news (or Gear Beer, Gear-Fist, Gear Shift, Jules is winning. For a moment . bonus rules!): twitter.com/SJGames. -

Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus

KICK Students’ magazine Publisher University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Publisher address Lorenza Jägera 9 31000 Osijek Language editing Ljubica Matek Editors Ljubica Matek Juraj Gerovac Vanessa Kupina Zvonimir Prtenjača Tomislav Berbić Proofreading Ljubica Matek Juraj Gerovac Zvonimir Prtenjača Tomislav Berbić Vanessa Kupina Cover design Ena Vladika ISSN 2623-9558 Br. 2, 2019. Printed by Krešendo, Osijek Printing run 100 copies The magazine is published twice a year. The magazine was published with the support of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek. Contents EDITORIAL ...................................................................................................... V Dr. Ljubica Matek, Assistant Professor Hope as the Main Driving Force of Humanity in the Grimdark Universe of Warhammer 40,000 ................................................. 7 Marcel Moser A New Approach to Religion in the Fantasy Genre .................................13 Juraj Gerovac A Capitalist Future in The Time Machine: A Social Statement and the Representation of the Bourgeois and the Proletariat ................21 Robert Đujić Voldemort or Grindelwald: Who Takes Place as the Number One Villain? ......................................................................................................27 Maligec Nikolina Man is not Truly Two, but Three: Psychoanalytical Approach to Personalities in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde ..............35 Katarina Stojković Nature vs. Nurture in the Case of the Monster in -

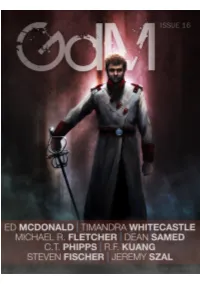

Grimdark Magazine Issue #16 Was Created by Jason Deem Based on Ed Mcdonald’S Story to See a Monster

1 Contents From the Editor Adrian Collins A Hero’s Guide to Fairy Tales Steven Fischer An Interview with Dean Samed Adrian Collins Review: War Cry Author: Brian McClellan Review by malrubius The Bronze Gods Jeremy Szal The Dark Lord and Grimdark C.T. Phipps Review: The Poppy War Author: R.F. Kuang Review by Matthew Cropley On the Dragonroad Timandra Whitecastle An interview with R.F. Kuang Matthew Cropley Crushing Dreams Michael R. Fletcher 2 To See a Monster Ed McDonald 3 Artwork The cover art for Grimdark Magazine issue #16 was created by Jason Deem based on Ed McDonald’s story To See a Monster. Jason Deem is an artist and designer residing in Dallas, Texas. More of his work can be found at: jdillustration.wordpress.com, on Twitter (@jason_deem ) and on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/JasonDeemIllustration). Language Grimdark Magazine has chosen to maintain the authors’ original language (eg. Australian English, American English, UK English) for each story. Legal Copyright © 2018 by Grimdark Magazine. All rights reserved. All stories, worlds, characters, and non-fiction pieces within are copyright © of their respective authors. The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or fictitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and unintended by the authors unless otherwise specified. 4 From the Editor ADRIAN COLLINS I feel like I say this every quarter lately, but bloody hell, what a quarter it’s been—non-stop pressure and deadlines from all angles, another bloody delay on Knee-Deep in Grit (a mercifully short one, this time), our new website hitting its straps, and the good fortune to all-but finish reading through our submissions inbox to pick out a few good ones. -

PDF Download Dragonslayer

DRAGONSLAYER: 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jasper Fforde | 304 pages | 16 Apr 2014 | Hodder & Stoughton General Division | 9781444707281 | English | London, United Kingdom Dragonslayer: 3 PDF Book Films based on Arthurian legends. Stone noticed that Rose had gone missing but Heath told him that they had to run away because more SandWings were coming their way. After you have repaired the ship, you may venture again to Crandor Island. Leaf shared his blueprint copy with his friends. A horizontal slash with less reach, but packs a punch. With help from Rhonu and Lorne, he successfully escapes with the eggs. She thought the tower containing the roaring dragon could be where prisoners were kept, but when food was brought in there was only enough for one dragon. Color: Color Metrocolor. Butterfly Attack The strange winged observers will rain fire on the battlefield, it's not accurate, but there are many bombing projectiles Stagger trap It looks like you've staggered him, and you can get free hits on him. Great read Good way to continue the series can't wait to see how it will play out in the next couple of books. Once the demon is defeated, open the final green door and take the map piece from the chest by completing the dialogue. I finished it slightly better writing, very little sex A ton of siege warfare against monster acid spitting frogs from the defenders viewpoint. Valerian's Father. May 01, Robert Mckillop rated it it was amazing. Valerian's Father Roger Kemp Aug 01, Dave Stone rated it liked it. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fairy Tales

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fairy Tales for Adults: Imagination, Literary Autonomy, and Modern Chinese Martial Arts Fiction, 1895-1945 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Lujing Ma Eisenman 2016 © Copyright by Lujing Ma Eisenman 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Fairy Tales for Adults: Imagination, Literary Autonomy, and Modern Chinese Martial Arts Fiction, 1895-1945 By Lujing Ma Eisenman Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Theodore D Huters, Chair This dissertation examines the emergence and development of modern Chinese martial arts fiction during the first half of the twentieth century and argues for the literary autonomy it manifested. It engages in the studies of modern Chinese literature and culture from three perspectives. First, approaching martial arts fiction as a literary subgenre, it partakes in the genre studies of martial arts fiction and through investigating major writers and their works explains how the genre was written, received, reflected, and innovated during the period in question. Second, positioning martial arts fiction as one of the most well received literary subgenre in the modern Chinese literary field, it discusses the “great divide” between “pure” and “popular” literatures and the question of how to evaluate popular literature in modern China. Through a series of textual analysis contextualized in the lineage of martial arts fiction, it offers insight into ii how the ideals of so-called “pure” and “popular” literatures were interwoven in the process of reviewing and re-creating the genre. -

Boss Monster Detailed Play Sequence.Docx

Greetings, Boss Monsters! If you’re eager to slay adventurers and build dungeons in Boss Monster, but the basic rulebook left you with some questions, you’ve come to the right place. Whether you’re looking to clarify a particular rule or delve into all the details, these rules expand upon what’s covered in the Boss Monster rulebook. In our experience, here are the top five rules clarifications requested by advanced gamers after an introductory session of Boss Monster: Treasure Type Matters, But Only For Advanced Rooms: You must build an Advanced Room on an ordinary or Advanced Room that matches its treasure type. Room subtype (Trap or Monster) does not need to match. You may build an ordinary Room adjacent to your dungeon entrance (if you have less than five visible Rooms in play) or on top of any other Room. You can always play an ordinary Room over another Room of any type, regardless of treasure type or room subtype. Destroyed Rooms Uncover What’s Beneath: When a Room is destroyed, the Room underneath it is uncovered and comes into play. This does not trigger "when you build this Room" effects from the uncovered Room. If a Hero is in a Room when it is destroyed, that Hero immediately exits the Room and (if it survives) moves to the next Room. (Damage and abilities of the Room underneath the destroyed Room do not affect the Hero exiting the Room.) If there is no Room underneath the revealed Room, the "hole" created by the destroyed Room immediately closes and any Rooms to the left of the destroyed Room slide to the right.