OBSERVATIONS on VERREAUX's EAGLE OWL Bubo Lacteus (Temminck)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenyan Birding & Animal Safari Organized by Detroit Audubon and Silent Fliers of Kenya July 8Th to July 23Rd, 2019

Kenyan Birding & Animal Safari Organized by Detroit Audubon and Silent Fliers of Kenya July 8th to July 23rd, 2019 Kenya is a global biodiversity “hotspot”; however, it is not only famous for extraordinary viewing of charismatic megafauna (like elephants, lions, rhinos, hippos, cheetahs, leopards, giraffes, etc.), but it is also world-renowned as a bird watcher’s paradise. Located in the Rift Valley of East Africa, Kenya hosts 1054 species of birds--60% of the entire African birdlife--which are distributed in the most varied of habitats, ranging from tropical savannah and dry volcanic- shaped valleys to freshwater and brackish lakes to montane and rain forests. When added to the amazing bird life, the beauty of the volcanic and lava- sculpted landscapes in combination with the incredible concentration of iconic megafauna, the experience is truly breathtaking--that the Africa of movies (“Out of Africa”), books (“Born Free”) and documentaries (“For the Love of Elephants”) is right here in East Africa’s Great Rift Valley with its unparalleled diversity of iconic wildlife and equatorially-located ecosystems. Kenya is truly the destination of choice for the birdwatcher and naturalist. Karibu (“Welcome to”) Kenya! 1 Itinerary: Day 1: Arrival in Nairobi. Our guide will meet you at the airport and transfer you to your hotel. Overnight stay in Nairobi. Day 2: After an early breakfast, we will embark on a full day exploration of Nairobi National Park--Kenya’s first National Park. This “urban park,” located adjacent to one of Africa’s most populous cities, allows for the possibility of seeing the following species of birds; Olivaceous and Willow Warbler, African Water Rail, Wood Sandpiper, Great Egret, Red-backed and Lesser Grey Shrike, Rosy-breasted and Pangani Longclaw, Yellow-crowned Bishop, Jackson’s Widowbird, Saddle-billed Stork, Cardinal Quelea, Black-crowned Night- heron, Martial Eagle and several species of Cisticolas, in addition to many other unique species. -

Raptors in the East African Tropics and Western Indian Ocean Islands: State of Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Status

j. RaptorRes. 32(1):28-39 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RAPTORS IN THE EAST AFRICAN TROPICS AND WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS: STATE OF ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION STATUS MUNIR VIRANI 1 AND RICHARD T. WATSON ThePeregrine Fund, Inc., 566 WestFlying Hawk Lane, Boise,1D 83709 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.--Fromour reviewof articlespublished on diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey occurringin Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands,we found most of the information on their breeding biology comesfrom subtropicalsouthern Africa. The number of published papers from the eastAfrican tropics declined after 1980 while those from subtropicalsouthern Africa increased.Based on our KnoM- edge Rating Scale (KRS), only 6.3% of breeding raptorsin the eastAfrican tropicsand 13.6% of the raptorsof the Indian Ocean islandscan be consideredWell Known,while the majority,60.8% in main- land east Africa and 72.7% in the Indian Ocean islands, are rated Unknown. Human-caused habitat alteration resultingfrom overgrazingby livestockand impactsof cultivationare the main threatsfacing raptors in the east African tropics, while clearing of foreststhrough slash-and-burnmethods is most important in the Indian Ocean islands.We describeconservation recommendations, list priorityspecies for study,and list areasof ecologicalunderstanding that need to be improved. I•y WORDS: Conservation;east Africa; ecology; western Indian Ocean;islands; priorities; raptors; research. Aves rapacesen los tropicos del este de Africa yen islasal oeste del Oc•ano Indico: estado del cono- cimiento eco16gicoy de su conservacitn RESUMEN.--Denuestra recopilacitn de articulospublicados sobre aves rapaces diurnas y nocturnasque se encuentran en Africa yen las islasal oeste del Octano Indico, encontramosque la mayoriade la informaci6n sobre aves rapacesresidentes se origina en la regi6n subtropical del sur de Africa. -

Systematic and Taxonomic Issues Concerning Some East African Bird Species, Notably Those Where Treatment Varies Between Authors

Scopus 34: 1–23, January 2015 Systematic and taxonomic issues concerning some East African bird species, notably those where treatment varies between authors Donald A. Turner and David J. Pearson Summary The taxonomy of various East African bird species is discussed. Fourteen of the non- passerines and forty-eight of the passerines listed in Britton (1980) are considered, with reference to treatments by various subsequent authors. Twenty-three species splits are recommended from the treatment in Britton (op. cit.), and one lump, the inclusion of Jackson’s Hornbill Tockus jacksoni as a race of T. deckeni. Introduction With a revision of Britton (1980) now nearing completion, this is the first of two pa- pers highlighting the complexities that surround some East African bird species. All appear in Britton in one form or another, but since that landmark publication our knowledge of East African birds has increased considerably, and with the advances in DNA sequencing, our understanding of avian systematics and taxonomy is con- tinually moving forward. A tidal wave of phylogenetic studies in the last decade has revolutionized our understanding of the higher-level relationships of birds. Taxa pre- viously regarded as quite distantly related have been brought together in new clas- sifications and some major groups have been split asunder (Knox 2014). As a result we are seeing the familiar order of families and species in field guides and checklists plunged into turmoil. The speed at which molecular papers are being published continues at an unprec- edented rate. We must remember, however, that while many molecular results may indicate a relationship, they do not necessarily prove one. -

W. TOMLINSON, Bird Notes from the NF District

JAN. 1950 W. TOMLINSON, Bird Notes from the N.F. District 225 BIRD NOTES CHIEFLY FROM THE NORTHERN FRONTIER DISTRICT OF KENYA PART II by W. Tomlinson. ALAUDIDAE Mirafra albicauda Reichenow. White-tailed Lark. Thika, April. Mirafra hypermetra hypermetra (Reichenow) Red-winged Bush-lark. Angata Kasut; Merille; Thika. In the Kasut to the south-west of Marsabit Mountain this large lark was fairly common,haunting a patch of desert where there was some bush and even grass following rain. Runs well in quick spurts; but, pursued, usually takes wing. The flight is strong, although it seldom goes far before ducking down again, usually perching on tops of bushes. In the heat of the day seen sheltering under bush. Has a clear and loud, two• Il)ted call and a very pretty song of four or fivenotes. The cinnamon-rufous of its plum• age shows in flight but is invisible in the bird when at rest. At Merille, the Kasut and at Th;ka, where this bird occurred, the ground was the same russet colour as the bird's plumage. Mirafra africana dohertyi Hartert Kikuyu Red-naped Lark. Thika; Nanyuki. Mirafra fischeri fischeri (Reichenow) Flappet Lark. Thika. Mirafra africanoides intercedens Reichenow. Masai Fawn-coloured Lark. Merille; North Horr. A " flappet-Iark," fairly common at Merille in January, was I think this. At the time a small cricket was in thousands in patches of open country, followed up by Larks and Wattled Starlings. Mirafra poecilosterna poecilosterna (Reichenow). Pink-breasted Singing Lark. Merille. A bird frequently flushed from the ground, which flew to bushes and low trees, was I think this. -

Kenya: Birds and Other Wildlife, Custom Trip Report

Kenya: Birds and Other Wildlife, custom trip report August 2014 Silvery-cheeked Hornbill www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Custom Tour Kenya August 2014 Kenya lies across the equator, ranging in altitude from 5199 m to sea level. The country’s topography and climate are highly varied, hence it exhibits many different habitats and vegetation types. Huge populations of wildlife are concentrated in protected areas, mainly national parks, national reserves, and conservancies. However, there are also opportunities to find a wealth of biodiversity in non-protected areas, as for example in Important Bird Areas (IBAs), some of which are found in non-protected areas, while others are located in protected areas. The IBAs provide a good chance to see some of the national or regional endemic species of both flora and fauna. They also provide opportunities for visitors to interact with local populations, which might be sharing their knowledge of indigenous life and traditional lifestyles. Our 15-day safari took us through unique and pristine habitats, ranging from the coastal strip of the Indian Ocean and its dry forest to the expansive savanna bushland of Tsavo East National Park, the semiarid steppes of Samburu National Park in northern Kenya, the mountain range of the Taita Hills, tropical rainforests, and Rift Valley lakes, before ending in the Masai Mara in southwestern Kenya. The variance of these habitats provided unique and rich wildlife diversity. Nairobi The city of Nairobi has much to offer its visitors. The Nairobi National Park is just seven kilometers away from the city and offers lots of wildlife. -

Species Recorded on the Mass Audubon Tour to Kenya and Tanzania October 30-November 20, 2010

Species Recorded on the Mass Audubon Tour to Kenya and Tanzania October 30-November 20, 2010 BIRDS AVES BIRDS 1 Common Ostrich Struthio camelus 43 Black Kite 2 Somali Ostrich Struthio molybdophanes 44 African Fish Eagle 3 Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 45 Palm-nut Vulture 4 Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 46 Hooded Vulture 5 Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus 47 Egyptian Vulture 6 Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo 48 White-backed Vulture 7 Long-tailed Cormorant P. africanus 49 Rueppell's Griffon 8 Grey Heron Ardea cinerea 50 Lappet-faced Vulture 9 Black-headed Heron Ardea melanocephala 51 White-headed Vulture 10 Goliath Heron Ardea goliath 52 Black-breasted Snake Eagle 11 Great Egret Ardea alba 53 Brown Snake Eagle 12 Intermediate Egret Egretta intermedia 54 Bateleur 13 Little Egret Egretta garzetta 55 Western Marsh Harrier 14 Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides 56 Pallid Harrier 15 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 57 Montagu's Harrier 16 Striated Heron Butorides striata 58 African Harrier-Hawk 17 Hamerkop Scopus umbretta 59 Dark Chanting Goshawk 18 Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis 60 Eastern Chanting Goshawk 19 African Open-billed Stork Anastomus lamelligerus 61 Gabar Goshawk 20 White Stork Ciconia ciconia 62 Shikra 21 Saddle-billed Stork Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis 63 Black Goshawk 22 Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumeniferus 64 Eurasian Buzzard 23 Sacred Ibis Threkiornis aethiopicus 65 Mountain Buzzard 24 Hadada Ibis Bostrychia hagedash 66 Augur Buzzard 25 Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus 67 Lesser Spotted Eagle 26 African Spoonbill -

Non-Chemical Control of the Red-Billed Quelea (Quelea Quelea) and Use of the Birds As a Food Resource

NON-CHEMICAL CONTROL OF THE RED-BILLED QUELEA (QUELEA QUELEA) AND USE OF THE BIRDS AS A FOOD RESOURCE BOAZ NDAGABWENE MTOBESYA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Master of Philosophy November 2012 DECLARATION I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not currently being submitted for any degree other than that of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil.) being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is a result of my own investigation except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised the work of others. name…………………………………………… (Boaz N. Mtobesya, Student) name……………………………………………… (Professor Robert A. Cheke, First Supervisor) name………………………………………………. (Dr Steven R. Belmain, Second Supervisor) (ii) D E D I C A T ION Dedicated to my God and Jesus Christ my Saviour in whose hands my life is. (iii) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First my sincere gratitude goes to almighty God who bestowed upon me his love and mercies throughout the entire period of my research. This work would not have been possible without Him and the help of my supervisors. I would like to express my profound gratitude to Professor Robert A. Cheke my first supervisor and my second supervisor Dr Steven R. Belmain for their invaluable advice and encouragement throughout the period of my research. Bob your constructive critique and kindness steered me along profitable pathways. Your visits in Tanzania during my field work, suggestions and thoughtfulness gave me the impetus to balance the tightrope of my research. -

New Records of IBA Criteria and Other Bird Species from the Dryland Hilltops of Kitui and Mwingi Districts, Eastern Kenya

Avifaunal Surveys of Hilltop forests in the semi-arid areas of Kitui and Mwingi Districts, Eastern Kenya. Ronald Kale Mulwa National Museums of Kenya, Ornithology Section, P.O. Box 40658 GPO Nairobi Contact email: [email protected] 1 KEY PROJECT OUTPUTS/MILE STONES 1. Involvement of local community members as field assistants enhanced capacity building, created awareness on the conservation of birds/biodiversity and generated some income through the wages they earned as field assistants. Exposure to use of binoculars and bird ringing. I assessed the existing local community groups as potential Site Support Groups (SSG) as they are termed in the Important Bird Areas framework. 2. The project offered a learning opportunity for two graduate interns in the Ornithology Department of National Museums of Kenya. They gained skills in bird survey methods and ringing and use of various equipments. 3. The project has led to immense filling up of knowledge gaps in this area, many birds were not known to occur in this area. Since survey has documented 5 Globally threatened bird species, discussions are under way to recognize as the area as an Important Bird Area (IBA). This is through BirdLife International and National Partner Nature Kenya. 4. For future monitoring a total of 363 individual birds in 35 species were ringed. These include resident, Afro-tropical and Palaearctic migratory species. 5. This project interaction with other projects in the area being executed by other institutional in collaboration with the local communities e.g. Bee keeping/Honey processing, Silk Worm rearing, Biodiversity monitoring, Horticulture & Woodlot nurseries, etc 6. -

True Bats (Microchiroptera) in the Diet of Verreaux's Eagle Owl Bubo Lacteus

50 Short Communications True bats (Microchiroptera) in the diet of Verreaux’s Eagle Owl Bubo lacteus Verreaux’s Eagle Owl Bubo lacteus is a large owl widespread in eastern and southern Africa and southern Central Africa, with a discontinuous distribution in West Africa (Marks et al. 1999, König & Weick 2008). It inhabits a wide variety of habitats such as woodlands, riparian forests, savannas, semi-deserts, deserts and even tropical rainforests in West and Central Africa (König & Weick 2008). It is an opportunistic predator; its diet has been recorded as comprising mainly mammals, such as rodents, insectivores, primates and fruit bats, plus small to large birds including passerines, ducks, herons, raptors and even smaller owls, such as Barn Owl Tyto alba and Spotted Eagle Owl B. africanus (Brown 1965, Avery et al. 1985, Marks et al. 1999, König & Weick 2008). In addition, it also takes reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects, spiders and scorpions and it has also been recorded feeding on carrion (Brown 1965, Marks et al. 1999, König & Weick 2008, Chittenden 2014). It is a crepuscular and nocturnal hunter and hunting near artificial lights has also been recorded (Brown 1965, Chittenden 2014). On 3 February 2015 we observed a Verreaux’s Eagle Owl perched on a tree branch in a streamside forest (1°43’26”N, 37°16’49”E) about 2 km from the Salato campsite near Ngurunit Village in foothills of the Ndoto Mountains, northern Kenya. Under its perch we found two pellets that contained three lower jaws and one upper jaw bone of bats, Chiroptera. These skeletal remains belonged to three individuals from two different species from the family Molossidae, and one individual of Lander’s Horseshoe Bat Rhinolophus landeri (Rhinolophidae). -

A Review of Alternatives to Fenthion for Quelea Bird Control

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Greenwich Academic Literature Archive 1 A REVIEW OF ALTERNATIVES TO FENTHION FOR QUELEA BIRD CONTROL 2 3 4 Robert A. Chekea* and Mohamed El Hady Sidattb 5 6 a Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich at Medway, Central Avenue, Chatham 7 Maritime, Chatham, Kent, ME4 4TB, UK 8 9 b Secretariat of the Rotterdam Convention, Plant Production and Protection Division (AGP 10 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Viale delle Terme di 11 Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy 12 13 14 *Corresponding author. 15 E-mail address: [email protected] (R. A. Cheke) 16 1 17 Keywords: red-billed quelea, Quelea quelea, fenthion, fire-bombs, integrated pest 18 management. 19 20 ABSTRACT 21 The red-billed quelea (Quelea quelea) is the most important avian pest of small grain crops in 22 semi-arid zones of Africa. Fenthion, an organophosphate, is the main avicide used for 23 controlling the pest but it is highly toxic to non-target organisms. The only readily available 24 pesticide that could replace fenthion is cyanophos, but this chemical is also highly toxic to 25 non-target organisms, although less so than fenthion, and may be more expensive; however, 26 more research on its environmental impacts is needed. Apart from chemical avicides, the only 27 rapid technique to reduce the numbers of quelea substantially is the use of explosives 28 combined with fuel to create fire-bombs but these also have negative effects on the 29 environment, can be dangerous and have associated security issues. -

Checklist of the Birds of Boni-Dodori

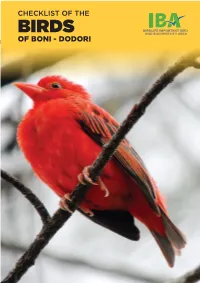

CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF BONI - DODORI CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF BONI - DODORI IBA Cover: Red-headed Weaver, Juba race Top right: Yellowbill, migrant from the south Top left: Common Cuckoo, migrant from the north Below: Senegal Plover ALL PHOTOS BY JOHN MUSINA CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF BONI - DODORI IBA CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF BONI - DODORI The Boni-Dodori Forest System The Boni-Dodori forest system is in the easternmost corner of Kenya, bordering Somalia and the Indian Ocean. It comprises Boni and Dodori National Reserves, Boni- Lungi and Boni-Ijara forests (which at the time of publication were understood to have recently been gazetted as Forest Reserves) and the Aweer Community Conservancy, proposed by the indigenous Aweer (Boni) people and the Northern Rangelands Trust. The Boni-Dodori area was designated Kenya’s 63rd Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) by Nature Kenya and BirdLife International in 2014. It forms part of the East African coastal forests biodiversity hotspot, an area known for globally significant levels of species richness and one of Africa’s centers of endemism. At the time of going to press, the area was under the control of the Kenya Defence Forces with restricted movement of the public. It is hoped that security will soon be restored and this remarkable landscape will be open to visitors again. This Checklist will be the first guide for visitors. The Landscape The Boni-Dodori forest system is a vast mosaic of east African coastal forest and thicket, seasonally flooded grassland and palm savanna, scattered wetlands and a strip of Acacia woodland. -

Kenya & Tanzania

Kenya & Tanzania V Trip report 2nd to 18th April 2014 (17 days) Rosy-throated Longclaw by Glen Valentine Trip Report and Images by Tour Leader: Glen Valentine Trip Report – RBT Kenya & Tanzania: Birds & Big Game V 2014 2 The East African countries of Kenya and Tanzania offer an almost unrivalled wildlife and birding safari. They each harbour more than 1000 species of birds and their famous game reserves and national parks boast some of the largest mammal concentrations of any places on earth! All this, combined with extremely easy and rewarding birding and mammal viewing in ideal, open-top and spacious safari vehicles, superb accommodation, wonderful food and awe- inspiring scenery ensures that one is treated to the most incredibly enjoyable birding adventure possible! Our tour began in the morning at our bird- rich lodge near Arusha where we were greeted by a good spread of new and exciting species. The dawn chorus was invigorating and revealed the likes of White- browed Robin-Chat and Grey- backed Camaroptera, two attractive and character-filled Bare-faced Go-away-bird species that would become particularly common as the tour progressed. During our short morning foray around the lodge grounds we picked up introductory species including African Emerald Cuckoo, Little Sparrowhawk, White-eared Barbet, appropriately- named Giant Kingfisher and the exquisite and localized Taveta Golden Weaver. Departing our lodge in the mid-morning we soon made our way through Arusha and south towards the fabulous Tarangire National Park, our first reserve