Mission and Recent Projects of the UCLA Cultural Virtual Reality Laboratory Bernard Frischer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eternal Fire of Vesta

2016 Ian McElroy All Rights Reserved THE ETERNAL FIRE OF VESTA Roman Cultural Identity and the Legitimacy of Augustus By Ian McElroy A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Classics Written under the direction of Dr. Serena Connolly And approved by ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Eternal Fire of Vesta: Roman Cultural Identity and the Legitimacy of Augustus By Ian McElroy Thesis Director: Dr. Serena Connolly Vesta and the Vestal Virgins represented the very core of Roman cultural identity, and Augustus positioned his public image beside them to augment his political legitimacy. Through analysis of material culture, historiography, and poetry that originated during the principate of Augustus, it becomes clear that each of these sources of evidence contributes to the public image projected by the leader whom Ronald Syme considered to be the first Roman emperor. The Ara Pacis Augustae and the Res Gestae Divi Augustae embody the legacy the Emperor wished to establish, and each of these cultural works contain significant references to the Vestal Virgins. The study of history Livy undertook also emphasized the pathetic plight of Rhea Silvia as she was compelled to become a Vestal. Livy and his contemporary Dionysius of Halicarnassus explored the foundation of the Vestal Order and each writer had his own explanation about how Numa founded it. The Roman poets Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Tibullus incorporated Vesta and the Vestals into their work in a way that offers further proof of the way Augustus insinuated himself into the fabric of Roman cultural identity by associating his public image with these honored priestesses. -

The Imperial Cult and the Individual

THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Ancient Mediterranean Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CLAIRE McGRAW Dr. Dennis Trout, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME presented by Claire McGraw, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________________ Professor Dennis Trout _______________________________________________ Professor Anatole Mori _______________________________________________ Professor Raymond Marks _______________________________________________ Professor Marcello Mogetta _______________________________________________ Professor Sean Gurd DEDICATION There are many people who deserve to be mentioned here, and I hope I have not forgotten anyone. I must begin with my family, Tom, Michael, Lisa, and Mom. Their love and support throughout this entire process have meant so much to me. I dedicate this project to my Mom especially; I must acknowledge that nearly every good thing I know and good decision I’ve made is because of her. She has (literally and figuratively) pushed me to achieve this dream. Mom has been my rock, my wall to lean upon, every single day. I love you, Mom. Tom, Michael, and Lisa have been the best siblings and sister-in-law. Tom thinks what I do is cool, and that means the world to a little sister. -

HSAR 252 - Roman Architecture with Professor Diana E

HSAR 252 - Roman Architecture with Professor Diana E. E. Kleiner Lecture 6 – Habitats at Herculaneum and Early Roman Interior Decoration 1. Title page with course logo. 2. Map of Italy in Roman times. Credit: Yale University. 3. Herculaneum, aerial view of ancient remains. Credit: Google Earth. 4. Herculaneum, view of ancient remains with modern apartment houses. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 5. Herculaneum, view of ancient remains. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 6. Casa a Graticcio, Herculaneum, general view. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. Wooden partition, Herculaneum [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Herculaneum_Casa_del_Tramezzo_di_Legno_-8.jpg (Accessed January 29, 2009). Bed, Herculaneum [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Herculaneum_Casa_del_Tramezzo_di_Legno_Letto.jpg (Accessed January 29, 2009). 7. Skeletons, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 556. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. Skeletons, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 562. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. 8. Rings, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 560 (bottom). Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. Bracelets, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 561. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. Skeleton of woman, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 560 top. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. 9. Skeleton of pregnant woman with fetus, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 564. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. 10. Crib with skeletal remains of an infant, Herculaneum. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/85949 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-07 and may be subject to change. KLIO 92 2010 1 65––82 Lien Foubert (Nijmegen) The Palatine dwelling of the mater familias:houses as symbolic space in the Julio-Claudian period Part of Augustus’ architectural programme was to establish „lieux de me´moire“ that were specifically associated with him and his family.1 The ideological function of his female relativesinthisprocesshasremainedunderexposed.2 In a recent study on the Forum Augustum, Geiger argued for the inclusion of statues of women among those of the summi viri of Rome’s past.3 In his view, figures such as Caesar’s daughter Julia or Aeneas’ wife Lavinia would have harmonized with the male ancestors of the Julii, thus providing them with a fundamental role in the historical past of the City. The archaeological evi- dence, however, is meagre and literary references to statues of women on the Forum Augustum are non-existing.4 A comparable architectural lieu de me´moire was Augustus’ mausoleum on the Campus Martius.5 The ideological presence of women in this monument is more straight-forward. InmuchthesamewayastheForumAugustum,themausoleumofferedAugustus’fel- low-citizens a canon of excellence: only those who were considered worthy received a statue on the Forum or burial in the mausoleum.6 The explicit admission or refusal of Julio-Claudian women in Augustus’ tomb shows that they too were considered exempla. -

Social Science

Myth at the heart of the Roman Empire The House of Augustus Rome Map: house of Augustus Augustus was an emperor: Caesar Augustus, one of the emperors of Rome. Augusto era imperatore: Caesar Augusto, era uno degli imperatori di Roma. He was the first emperor. As a child he was also seen as the future saviour of Rome. E' stato il primo imperatore che e' stato visto anche come il bambino che avrebbe salvato Roma. The house of Augustus is right next to the entrance to the Roman Forum. C'e' la casa di Augusto proprio nell'entrata del Foro Romano. Chris Smith: So this is the House of Augustus. It's an incredibly exciting site, because what we get to see here is the choices that an emperor has made about where he wants to live. Chris Smith: Through to the green that you can see underneath the archway here is effectively the end of the palatine, edge of the palatine. That leads you down into this incredibly rich sacral landscape. Which ultimately leads to the Tiber. And of course the Lupercal. The Lupercal, the place where Romulus and Remus wound up after they'd been put into a little boat and sent off to die. That's where they were suckled by a wolf, taken in by a shepherd and so forth, so there's a direct story of Romulus and Remus at the Lupercal there. Chris Smith: At the same time, if we look down this line here, what we're effectively seeing is a row of temples, and there's another behind us over there, which contextualise this house in a highly religious topography from the middle republic to contemporary with Augustus. -

“Empire Without End”: Augustan Rome and the Founding of the Principate Humanities and Religious Studies 196A

“Empire without End”: Augustan Rome and the Founding of the Principate Humanities and Religious Studies 196A A focused study of Roman cultural history at the time of the transition, orchestrated primarily by the emperor Augustus, from the republic to the principate (or empire). Emphasis will be on understanding Augustan values through attention to the literature, visual arts, architecture, and governmental, social, and economic policies that helped to establish the principate according to Augustus’ vision. Course time in Rome will be devoted primarily to visiting archaeological sites, monuments, and museum collections, and to ongoing discussion of their relationship to important literary works (to be studied prior to departure), and of the relevance of all these various manifestations of Augustan culture to the emperor’s program of reform. Expected Learning Outcomes Students will be able to: • Summarize the historical framework of the late republican and early imperial periods (i.e., 133 BCE to 68 CE) and explain key historical events for understanding Augustan culture • Define auctoritas as it applies to Augustus and the Augustan period, and cite examples drawn from various forms of literature and material culture • Identify traditional Roman values that Augustus emphasized, and explain how these values were manifested in Augustan culture • Describe a wide variety of literary works, archaeological sites, and architectural and artistic achievements from the Augustan period • Differentiate the main political and social components of the republican period from those of the early principate • Identify examples of Augustan influence on subsequent historical developments, as manifested in cultural features of Rome Course Requirements Required readings • Karl Galinsky, Augustan Culture • Selected readings to be assigned by instructor (e.g. -

Ancient Rome & the Renaissance

Introducing Choose your travel companions | Select your dates Private Departures: Opt for 3-, 4-, or 5-star accommodations Ancient Rome & the Renaissance: Art, Architecture & Cuisine Five nights in Rome | Two nights in Naples | Three nights in Amalfi © L-BBE © Derbrauni Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur. Dear Traveler, Schedule your own, private AIA Tour that fits your travel dates and your budget. Travel with expert local guides who also handle all of the logistics, so you can relax and immerse yourself in learning and experiencing ancient and Renaissance art and architecture, including numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites. Enjoy delicious food and wine, and hand-picked 3-, 4-, or 5-star hotels, all perfectly located for exploring on your own during free time: five nights in central Rome, two nights in Naples (where 4- and 5-star hotels overlook the Bay of Naples), and three nights in Amalfi overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea. © WolfgangRieger Your wonderful, expert-guided excursions are many and include: Above: Mosaic at Naples Archaeological Museum. Below: A courtyard at Rome's • The Roman Forum, with a private visit to the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina; Capitoline Museums. • Special entry to the Colosseum's upper levels and underground tunnels; • Stunning paintings and mosaics at the Palatine Hill and House of Augustus; • The Capitoline Museums, with their magnificent Classical and Renaissance art; • Outstanding Renaissance sculptures and paintings at the Borghese Gallery; • Breakfast within the Vatican Museums -

Rome Architecture Guide 2020

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Ancient Rome The Flavium Amphitheatre was built in 80 AD of concrete and stone as the largest amphitheatre in the world. The Colosseum could hold, it is estimated, between 50,000 and 80,000 spectators, and was used The Colosseum or for gladiatorial contests and public spectacles such as mock sea Amphitheatrum ***** Unknown Piazza del Colosseo battles, animal hunts, executions, re-enactments of famous battles, Flavium and dramas based on Classical mythology. General Admission €14, Students €7,5 (includes Colosseum, Foro Romano + Palatino). Hypogeum can be visited with previous reservation (+8€). Mon-Sun (8.30am-1h before sunset) On the western side of the Colosseum, this monumental triple arch was built in AD 315 to celebrate the emperor Constantine's victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (AD 312). Rising to a height of 25m, it's the largest of Rome's surviving ***** Arch of Constantine Unknown Piazza del Colosseo triumphal arches. Above the archways is placed the attic, composed of brickwork revetted (faced) with marble. A staircase within the arch is entered from a door at some height from the ground, on the west side, facing the Palatine Hill. The arch served as the finish line for the marathon athletic event for the 1960 Summer Olympics. The Domus Aurea was a vast landscaped palace built by the Emperor Nero in the heart of ancient Rome after the great fire in 64 AD had destroyed a large part of the city and the aristocratic villas on the Palatine Hill. -

Roman Images of Diana Bettina Bergmann Mount Holyoke College

! "! A Double Triple Play: Roman Images of Diana Bettina Bergmann Mount Holyoke College John Miller’s study of Augustan Apollo inspired me to return to Paul Zanker’s The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (1988), a book that demonstrated the immense potential of an interdisciplinary approach rather than exclusive focus on any one artistic mode. Nearly a quarter of a century later, this session continues to grapple with the challenges of interdisciplinarity and assessment of the Augustan era. Miller’s subtle analysis of poets’ intricate language invites a renewed consideration of the relationships among texts, sites, and images. The operations that he describes -- conflating, juxtaposing, allusion, correspondence, association – can be related directly to the analysis of topography and monuments as well. I also would like to extend his recommendation to “analyze variations in light of one another” and consider visual images of an elusive figure in his book, the divine twin Diana. The goddess appears, often as an afterthought, literally placed in parentheses after a mention of Apollo, until she assumes prominence in Miller’s insightful treatment of the saecular games (Chapter Five). As I will argue, however, in the visual environment of Augustan Rome, she would have been impossible to bracket out. While the goddess, fiercely independent, often appeared alone, in the second half of the first century B.C.E. she became a faithful companion of Apollo. Diva triformis The late republic and early empire saw an explosion of images of the divine sister, who, like Apollo, evolved into a dynamic, shape-shifting deity, slipping from one identity to another: Hecate, Trivia, Luna, Selene, even Juno Lucina. -

IU Letter Template

BERNARD FRISCHER Curriculum Vitae and List of Publications (January 15, 2015) Home Address: 500 East Moss Creek Drive, Bloomington, IN 47401 Phone number: 310-266-0183 (cell) E-mail: [email protected] Home page: www.frischerconsulting.com/frischer Media coverage: http://www.romereborn.virginia.edu/press.php#media_coverage Born: May 23, 1949 Citizenship: USA EMPLOYMENT PROFESSOR, Department of Informatics, Indiana University, 2013—present EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 2012—present SENIOR SCIENTIST, PublicVR, a non-profit research corporation, 2011—present SENIOR FELLOW, Zukunftskolleg, University of Konstanz, 2010-11 VISITING PROFESSOR, College of Computer Science, Beijing Normal University, September 2009 PROFESSOR, History of Art, University of Virginia, 2004—2013 (tenured) PROFESSOR, Classics Department, University of Virginia, 2004—2013 (tenured) DIRECTOR and FOUNDER, Virtual World Heritage Laboratory, U. of Virginia and Indiana University, 2009—present DIRECTOR, Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, U. of Virginia, 2004—2009 PROFESSOR-IN-CHARGE, Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies, Rome, 2001-02 DIRECTOR and FOUNDER, UCLA Cultural Virtual Reality Lab, 1998—2004 DIRECTOR, UCLA office of the UC Education Abroad Program, 1992-1998 VISITING PROFESSOR, University of Pennsylvania, Fall Semester, 1994 VISITING PROFESSOR, University of Bologna, Fall Semester, 1993 DIRECTOR, Italy Study Center of the University of California Education Abroad Program, 1988-90 DIRECTOR, UCLA Humanities Computing Facility, 1987-88 CHAIR, UCLA Department of Classics, 1984-1988 PROFESSOR, Classics UCLA, July, 1976—June, 2004 (tenure was earned in 1980) FELLOW, American Academy in Rome, 1974—76 EDUCATION/DEGREES Fellow of the American Academy in Rome, Classical Studies, 1976 Ph.D. -

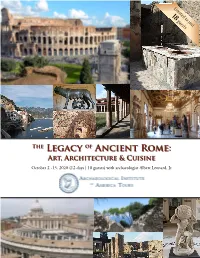

The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 2 -13, 2020 (12 Days | 18 Guests) with Archaeologist Albert Leonard, Jr

Limited to just Limited to just 18 18 travelers guests © Derbrauni The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 2 -13, 2020 (12 days | 18 guests) with archaeologist Albert Leonard, Jr. Dear Traveler, Next October, when the weather is typically perfect, discover the glorious legacy of ancient Rome with the AIA’s Dr. Al Leonard, recipient of many awards and a popular AIA Tours lecturer and host. With expert local guides plus a professional tour manager to handle all of the logistics, you can relax and immerse yourself in learning and experiencing ancient and Renaissance art and architecture, including numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites. Enjoy delicious food and wine, and excellent, 4-star hotels, perfectly located for exploring on your own during free time: five nights in central Rome, two nights in Naples overlooking the Bay of Naples, and three nights in Amalfi overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea. © Carla Tavares Highlights are many and include: • The Roman Forum, with a private visit to the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina; and special entry to the Colosseum's upper levels; • Stunning paintings and mosaics at the House of Augustus on the Palatine Hill; • The Capitoline Museums, with their magnificent Classical and Renaissance art; • Outstanding Renaissance sculptures and paintings at the Borghese Gallery; • A day trip to Tivoli for visits to Hadrian’s Villa, a 2nd-century A.D. complex; and Villa d’Este, a superb Renaissance palace. • Breakfast within the Vatican Museums, before entering the Sistine Chapel © Intel Free -

The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 14 -25, 2021 (12 Days | 16 Guests) with Archaeologist Ingrid Rowland

Limited to just Limited to just 18 16 travelers guests © Derbrauni © operator The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 14 -25, 2021 (12 days | 16 guests) with archaeologist Ingrid Rowland © MrNo “The archaeological sites are the things that caused me to select Archaeological Institute of this tour. The great buildings and ensembles of architectural America Lecturer and Host interest were such a thrill that I will never forget.” - Charles, New York Ingrid Rowland first came to Italy on the ocean liner Leonardo da Vinci. With a Ph.D. in Greek ITALY Adriatic Sea and Classical Tivoli Archaeology 5 ROME from Bryn Mawr, Sperlonga she branched out into Renaissance Capua Herculaneum and Baroque NAPLES 3 studies, and Tyrrhenian Sea Capri 2 AMALFI recently into Paestum contemporary art. Ingrid has studied and Pompeii taught in Rome for many years, and is now Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame’s Rome Global Gateway. Prior to that appointment, she served as the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the = Flights Humanities at the American Academy in = Itinerary stops Rome (2001-05), and then Professor in the = Overnight stays Rome Program of the Notre Dame School of Architecture (2005-). A frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books, she has written more than a dozen books on Italian subjects, ranging from the ancient Etruscans to the present day, including The Divine Spark of Syracuse (2018), From Pompeii: The Afterlife of a Roman Town (2015), and, with Noah Charney, The Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art (2017).