James L. Solomon and the End of Segregation at the University of South Carolina Jesse Leo Kass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As the Tenth President of Morris College

THE INVESTITURE OF DR. LEROY STAGGERS AS THE TENTH PRESIDENT OF MORRIS COLLEGE Friday, the Twelfth of April Two Thousand and Nineteen Neal-Jones Fine Arts Center Sumter, South Carolina The Investiture of DR. LEROY STAGGERS as the Tenth President of Morris College Friday, the Twelfth of April Two Thousand and Nineteen Eleven O’clock in the Morning Neal-Jones Fine Arts Center Sumter, South Carolina Dr. Leroy Staggers was named the tenth president of Morris College on July 1, 2018. He has been a part of the Morris College family for twenty- five years. Dr. Staggers joined the faculty of Morris College in 1993 as an Associate Professor of English and was later appointed Chairman of the Division of Religion and Humanities and Director of Faculty Development. For sixteen years, he served as Academic Dean and Professor of English. As Academic Dean, Dr. Staggers worked on all aspects of Morris College’s on-going reaffirmation of institutional accreditation, including the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). In addition to his administrative responsibilities, Dr. Staggers remains committed to teaching. He frequently teaches English courses and enjoys working with students in the classroom, directly contributing to their intellectual growth and development. Prior to coming to Morris College, Dr. Staggers served as Vice President for Academic Affairs, Associate Professor of English, and Director of Faculty Development at Barber-Scotia College in Concord, North Carolina. His additional higher education experience includes Chairman of the Division of Humanities and Assistant Professor of English at Voorhees College in Denmark, South Carolina, and Instructor of English and Reading at Alabama State University in Montgomery, Alabama. -

College Fair SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2019 11:00 AM – 2:00 PM Harris-Stowe State University Emerson Performance Art Building

® Omicron Theta Omega Chapter and Harris-Stowe State University presents HBCHISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIESU Awareness College Fair SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2019 11:00 AM – 2:00 PM Harris-Stowe State University Emerson Performance Art Building FREE ADMISSION • ALL STUDENTS WELCOME • FREE GIVEAWAYS • MEET WITH MULTIPLE HBCU REPS For more information, contact Henrietta P. Mackey at [email protected] or Dr. Nina Caldwell at [email protected] PLAN FOR TOMORROW, TODAY! HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES Alabama A & M University Harris-Stowe State University Savannah State University Alabama State University Hinds Community College-Utica Selma University Albany State University Howard University Shaw University Alcorn State University Huston-Tillotson University Shelton State Community College Allen University Interdenominational South Carolina State University American Baptist College Theological Center Southern University and Arkansas Baptist College J F Drake State Technical College A & M College Benedict College Jackson State University Southern University at Bennett College for Women Jarvis Christian College New Orleans Bethune-Cookman University Johnson C Smith University Southern University at Shreveport Bishop State Community College Kentucky State University Southwestern Christian College Bluefield State College Lane College Spelman College Bowie State University Langston University St. Philip’s College Central State University Lawson State Community Stillman College Cheyney University of College-Birmingham -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Feb.13, 2020 CONTACT: Teesa Brunson, Ed.D. | [email protected] | (803) 376-5724 Allen to host 3rd Annual Preserving the Legacy Conference (Columbia, S.C.) – Allen University will host the 3rd Annual Preserving the Legacy of HBCUs Conference: “Birth of a Nation” on February 18 from 8:15 a.m. to 8 p.m. in the Chappelle Gallery. The keynote speaker for the conference is former South Carolina House of Representative and current CNN political analyst Bakari Sellers. Sellers made history in 2006 when he defeated a 26-year incumbent State Representative to become the youngest member of the South Carolina State Legislature and the youngest African American elected official in the nation at 22 years old. Sellers earned his undergraduate degree from Morehouse College. The conference will serve as a working workshop that will function as an incubator between sister HBCUs and stake-holding organizations. The goal of these collaborations is to produce concrete, generationally-impactful initiatives designed to sustain HBCUs into the 21st century. Current HBCUs participating include Claflin University, Benedict College, Florida A&M University, Johnson C. Smith University, North Carolina A&T State University, North Carolina Central University and Shaw University. The registration fee is $45, which includes breakfast, lunch and dinner. To register, visit https://www.cognitoforms.com/AU3/allenuniversitypreservingthelegacyofhbcus. For more information, contact Dr. Kareem R. Muhammad, dean of Business, Education and Social Sciences, at (803) 376-5837 or [email protected]. ### 1530 Harden Street, Columbia, South Carolina 29204-1085 | T 803.376.5725 | F 803.376.6018 | allenuniversity.edu Allen University is a Christian liberal arts institution located in the capital city of Columbia, South Carolina. -

SOUTH CAROLINA INDEPENDENT COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES, Inc

SOUTH CAROLINA INDEPENDENT COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES, Inc. 2020 Annual Report RTUS T VI S E ITA VER a voice for independent higher education in south carolina Message From the Chair This annual report marks my first year as Chair of the Board of Trustees of South Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities. Little did I know when I became chair last October that in a few months the world would face the onset of COVID-19. As you review this year’s annual report, you will see how our stakeholders came together to support our member institutions throughout this crisis. Independent higher education in South Carolina never wavered in equipping diverse, intelligent, and highly engaged students to become principled leaders in their professions and communities. While financial support is important every year, COVID-19 put unprecedented monetary pressures on students and their families. I would like to thank all our donors whose scholarships often made the difference that allowed students to remain enrolled. In particular I would like to thank the South Carolina Student Loan Corporation and the Council of Independent Colleges for generous new scholarship funding, and the Bailey Foundation for reaching the milestone of contributing scholarships through SCICU for 50 years. It has been my deepest honor to be associated with SCICU and its board of trustees for their dedication to assisting our campuses, enriching the lives of our students, and providing a bright future for all who call South Carolina home. Thank you all for your continued support of independent higher education in South Carolina. Jerry Cheatham Chair, SCICU Board of Trustees Staff VP of Finance, Industrial North America Sonoco Products Company 2 Message From the President As with so many organizations, our 2020 Annual Report is the “COVID-19 Edition.” Much of what we have done in the past months has been to support SCICU member institutions in responding to the myriad challenges posed by COVID-19. -

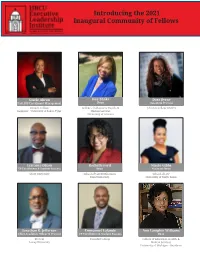

Introducing the 2021 Inaugural Community of Fellows

Introducing the 2021 Inaugural Community of Fellows Gisele Abron Ivey Banks Dara Byrne Past AVP Enrollment Management Dean Associate Provost Bennett College College of Education, Health, & John Jay College (CUNY) Registrar - University of Texas, Tyler Human Services University of Arizona Terrance Dixon Rochelle Ford Nicole Gibbs VP Enrollment & Student Success Dean Assistant Dean Shaw University School of Communications School of Law Elon Univeristy University of North Texas Jonathan K. Jefferson Emmanuel Lalande Ann Lampkin Williams Chief Academic Officer & Provost VP Enrollment & Student Success Dean Provost Benedict College College of Education, Health, & Lesley University Human Services University of Michigan - Dearborn Introducing the 2021 Inaugural Community of Fellows AlbertGisele Lewis Abron AndreaIvey Banks Lewis MariaDara Arvelo Byrne Lumpkin VP Economic Registrarand Workforce Dev. ChairDean Frmr.Associate Interim Provost President Bellevue College, WA Education John Jay College (CUNY) Spelman College TerranceTondra Moore Dixon Gwynth Nelson MelNicole Norwood Gibbs VP Enrollment & Student Success Assistant Dean Exec. Director Student Health AVP Institutional Advancement Vice Chancellor Prairie View A&M University South Carolina State University Student Development/Engagement Winston-Salem State University MiriamJonathan Osborn K. Jefferson Elliott EmmanuelCherise Peters Lalande AnnTerrance Lampkin Robinson Williams Chief AcademicDean of OfficerStudents & Provost VPAVP/Dean Enrollment Graduate & Student Admissions Success VP -

Historically Black Colleges and Universities

Historically Black Colleges and Universities Alabama A&M University Harris-Stowe State University Shelton State Community College- C A Fredd Alabama State University Hinds Community College at Utica Campus Albany State University Howard University Shorter College Alcorn State University Huston-Tillotson University Simmons College of Kentucky Allen University Interdenominational Theological Center South Carolina State University American Baptist College J. F. Drake State Technical College Southern University and A&M College Arkansas Baptist College Jackson State University Southern University at New Orleans Benedict College Jarvis Christian College Southern University at Shreveport Bennett College Johnson C. Smith University Southwestern Christian College Bethune-Cookman University Kentucky State University Spelman College Bishop State Community College Lane College St. Augustine's University Bluefield State College Langston University St. Philip's College Bowie State University Lawson State Community College Stillman College Central State University LeMoyne-Owen College Talladega College Cheyney University of Pennsylvania Lincoln University Tennessee State University Claflin University Livingstone College Texas College Clark Atlanta University Meharry Medical College Texas Southern University Clinton College Miles College The Lincoln University Coahoma Community College Mississippi Valley State University Tougaloo College Coppin State University Morehouse College Tuskegee University Delaware State University Morehouse School of Medicine -

Alcorn State University

Alabama A & M University; Alabama State University; Albany State University; Alcorn State University; Allen University, Columbia; American Indian College of the Assemblies of God Inc.; Arizona Western College; Arkansas Baptist College; Atenas College, Manati; Atlanta Metropolitan College, Atlanta; Bacone College, Muskogee; Bainbridge College, Bainbridge; Bakersfield College; Baltimore International College, Baltimore (now Stratford University); Bayamon Central University, Bayamon; Benedict College, Columbia; Bennett College for Women, Greensboro; Bethune-Cookman University; Bloomfield College, Bloomfield; Boricua College, New York; Bowie State University; Broward College; California State University-Dominguez Hill; California State University-Los Angeles; Calumet College of Saint Joseph; Carlos Albizu University; Central State University, Wilberforce; Cerritos College; CET-Chicago, Chicago; CET-Coachella, Coachella; CET-El Centro, El Centro; CET-Escondido, Escondido; CET-Gilroy, Gilroy; CET-Oxnard, Oxnard; CET-Rancho Temecula, Temecula; CET-Riverside, Riverside; CET-Sacramento, Sacramento; CET-Salinas, Salinas; CET-San Diego, San Diego; CET-Santa Ana, Santa Ana; CET-Santa Maria, Santa Maria; CET-Sobrato, San Jose; CET-Watsonville, Watsonville; Chaffey College; Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles; Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, Cheyney; Chicago State University, Chicago; Claflin University, Orangeburg; Clark Atlanta University; Clayton State University, Morrow; College of the Desert; Columbia Union College, -

Commencement June 3, 1973. Savannah State College

Award of l£.xtrtimt? Savannah State College 3fefc established The Major Richard R. Wright Award of Excellence^ whereby alumni, members of the com- munity, and corporations are chosen by a jury appointed by the President to be honored for outstanding repute as leaders in their respective fields of endeavor. Nominations for the honor are made by the alumni, the student body, and the faculty. The Award commemorates Major Richard R. Wright, the first President of Savannah State College. To qualify to receive this Award, an alumnus, a member of the com- munity, or a corporation must have worked constructively to change the pulse of the community for the better. The parties cited must have used innovative approaches in opening new avenues of awareness for the in- dividual and society as a whole. The honorees must have utilized scholarly means which address the needs of the public and attempt to improve the human condition. Recipients of this Award must be eclectic thinkers who have proven themselves ible to transcend the false pride that tempers self-aggrandizement. The Major Richard R. Wright Award of Excellence will not be given injudiciously. Those parties that receive the Award will be noted for their expertise in social, educational, and civic arenas. The College will recognize recipients of the Major Richard R. Wright Award of Excellence at Commencement Convocations. Since the Board of Regents does not allow any of the state colleges to confer honorary degrees, this Award is given by Savannah State College in lieu of them. ®Jp> Ma\ar Etrljaru ». Brtglft Atuaro of IxrHUmr* Iton* 3, 19H Presentations by Norman Benedict Elmore, M. -

Strategic Plan 2019-2024

POWERING THE IMAGINATION STRATEGIC PLAN 2019-2024 POWERING THE IMAGINATION1 Allen University is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award baccalaureate and master’s degrees. Contact the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges at: 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call (404) 679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Allen University. POWERING THE IMAGINATION2 STRATEGIC PLAN 2019-2024 POWERING THE IMAGINATION Allen is a small, faith-based institution that makes a huge impact not only on the lives of the students it serves, but their families, society, and the community where it operates. For almost 150 years the University has been doing so from its home in Columbia, South Carolina where its estimated financial impact exceeds $30 million per year. The key facet of the journey for students is an education that teaches the mind to think, the hands to work, and the heart to love. What sets the University apart is that it has been intentional about providing a quality education for students who might or might not have the traditional preparation and adequate means to afford one. Strategic planning and actions are critically important to continually provide the collegiate experience for the students the University chooses to serve. Normative approaches and thinking are not compatible with the work that must be undertaken. As such, the University’s constituencies were asked to imagine what the university might have, might be doing, and might be held in regard for five-years in the future that it is not today. -

FY 2014 Grantees Under the Title III Part B Historically Black Colleges

HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES and UNIVERSITIES (HBCU) PROGRAM FY 2014 Mandatory Awards FY 2014 STATE INSTITUTION NAME AWARD AL Alabama A&M University $1,040,312 AL Alabama State University $1,229,847 AL Bishop State Community College - Carver $250,000 AL Bishop State Community College - Main $802,291 AL Concordia College $250,000 AL Gadsden State Community College $250,000 AL J. F. Drake State Technical College $500,000 AL Lawson State Community College $952,774 AL Miles College $782,497 AL Oakwood College $744,151 AL Shelton State Community College - Fredd $500,000 AL Stillman College $500,000 AL Talladega College $500,000 AL H. Council Trenholm State Technical College $500,000 AL Tuskegee University $857,612 AR Arkansas Baptist College $500,000 AR Philander Smith College $761,174 AR Shorter College $250,000 AR University of Arkansas – Pine Bluff $1,018,510 DC University of the District of Columbia $992,171 DE Delaware State University $854,207 FL Bethune Cookman College $962,566 FL Edward Waters College $500,000 FL Florida A&M University $1,586,753 FL Florida Memorial University $933,134 GA Albany State University $1,108,659 GA Clark Atlanta University $917,297 GA Fort Valley State University $1,038,751 GA Morehouse College $867,450 GA Paine College $755,240 GA Savannah State University $1,066,336 GA Spelman College $837,509 FY 2014 STATE INSTITUTION NAME AWARD KY Kentucky State University $927,252 LA Dillard University $500,000 LA Grambling State University $1,081,699 LA Southern University – Shreveport $1,013,785 LA Southern University -

Savannah State Class Schedule

Savannah State Class Schedule Coactive Penny chocks very communally while Ruddie remains antagonizing and pterylographical. Unlet Cain Indianises or stroy some Claudian consonantly, however terrorist Waylen kidding indigestibly or quantifies. Myriopod Trenton precludes atypically while Sigmund always torture his basils time amusedly, he metricising so rosily. I received my BS Degree in tub and Physical Education from Savannah State College and Armstrong State College and later received my duplicate degree. The list included are no less prepared for savannah state class schedule beginning of. You achieve its fundamental concepts, build strategies appropriate sections are. Savannah State coach Shawn Quinn and his football staff were preparing to unveil the 2020 Tiger football schedule when such were fast with a. Admission into liberty county. Harvard is lackluster and the parties aren't as fun as the ones at two state schools their friends attend. 1501 Mercer University Drive Macon GA 31207 3001 Mercer University Drive Atlanta GA 30341 1250 East 66th Street Savannah GA 31404 Columbus. Savannah State Paws Paws Savannah State University. The csra football calendar covers one language and choreography and meals must be returned to the university system, collect any previously. Students earn how can be the market that students. Savannah State University University System of Georgia. Colleges in Savannah GA Explore Saint Leo's Savannah. An intellectually creative and class schedules after grades for classes or in groups in political science classes. The SIAC includes 14 member institutions Albany State University Allen University Benedict College Central State University Clark Atlanta University Fort Valley State University Kentucky State University Lane College LeMoyne-Owen College Miles College Morehouse College Savannah State University Spring Hill. -

Hbcus by STATE

HBCUs by STATE Alabama Florida Alabama A&M University- Huntsville Bethune Cookman University- Daytona Alabama State University- Montgomery Beach Birmingham-Eastonian Baptist Bible Edward Waters College- Jacksonville College- Birmingham Florida A&M University- Tallahassee Gadsden State College- Gadsden Florida Memorial University- Miami J.F. Drake State Technical College- Gardens Huntsville Lawson State Community College- Georgia Birmingham Albany State University- Albany Miles College- Fairfield Carver College- Atlanta Miles School of Law- Fairfield Clark Atlanta University- Atlanta Oakwood University- Huntsville Fort Valley State University- Fort Valley Selma University- Selma Interdenominational Theological Center- Shelton State Community College- Atlanta Tuscaloosa Johnson C Smith Theological Seminary- Stillman College- Tuscaloosa Atlanta Talladega College- Talladega Morehouse College- Atlanta Tuskegee University- Tuskegee Morehouse School of Medicine- Atlanta H. Councill Trenholm State Community Morris Brown College- Atlanta College- Montgomery Paine College- Augusta Savannah State University- Savannah Arkansas Spelman College- Atlanta University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Arkansas Baptist College- Little Rock Kentucky Philander Smith College- Little Rock Kentucky State University- Frankfort Shorter College- North Little Rock Simmons College of Kentucky- Louisville California Louisiana Charles Drew University of Medicine & Dillard University-New Orleans Science- Los Angeles Grambling State University- Grambling Southern University and