Memoirs of a Great Detective, Incidents in the Life of John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Nations Women Teachers at Grand River in the Early Twentieth Century Alison Norman

Document generated on 09/24/2021 6:07 a.m. Ontario History “True to my own noble race” Six Nations Women Teachers at Grand River in the early Twentieth Century Alison Norman Women and Education Article abstract Volume 107, Number 1, Spring 2015 While classrooms for Indigenous children across Canada were often taught by non-Indigenous men and women, at the Six Nations of Grand River, numerous URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1050677ar Haudenosaunee women worked as teachers in the day schools and the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1050677ar residential school on the reserve. While very different from each other, Emily General, Julia Jamieson and Susan Hardie shared a passion for educating the See table of contents young of their community, especially about Haudenosaunee culture and history, along with the provincial curriculum. They were community leaders, role models and activists with diverse goals, but they all served their community through teaching, and had a positive impact on the children they Publisher(s) taught. The Ontario Historical Society ISSN 0030-2953 (print) 2371-4654 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Norman, A. (2015). “True to my own noble race”: Six Nations Women Teachers at Grand River in the early Twentieth Century. Ontario History, 107(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050677ar Copyright © The Ontario Historical Society, 2015 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Memoirs of a Great Detective; Incidents in the Life of John Wilson Murray

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08236547 3 A BURY John Wilson Murray Memoirs of A Great Detective INCIDENTS IN THE LIFE OF JOHN WILSON MURRAY EDITED BY VICTOR SPEER WITH PORTRAIT «$? NEW YORK THE BAKER & TAYLOR CO. 33-37 East Seventeenth Street, Union Sq., North Copyright, 1904, 1905, by '" "*' VICTOR SPEER and JOHN W. MURRAY • * '") ) \ CONTENTS I. Murray ...... 9 II. From Babyhood to Battleship . H III. The First Case : Confederate Cole's Coup *9 IV. A Word by the Way .... 29 V. Knapp : A Weazened Wonder 35 VI. The Feminine Firm of Hall and Carroll 42 VII. The Episode of Poke Soles 47 VIII. How a Feud Almost Burned Erie 5° IX. Two Scars, by the Blade of Napper Nichols bullet and the of Whitey Stokes . 54 X. A King, a Lunatic, and a Burglar—Three in One, and none at all ... 57 XI. The Box-Car Battle of Sweetman, and the Thrashers with the Wheat 63 XII. With the Help of Jessie McLean 69 XIII. The Course of a Career 71 XIV. Sanctimonious Bond .... 76 XV. When Ralph Findlay Lurched and Fell . 81 XVI. The Tinkling House of Wellington Square 89 XVII. The Driverless Team on Caledonia Road . 93 XVIII. Apropos of Hunker Chisholm . 98 XIX. The Whitesides of Ballinafad . 101 XX. The Monaghan Murder 104 The Six -Foot Needhams : Father and Son . 108 Pretty Mary Ward of the Government Gardens, 116 XXIII. The Fatal Robbery of the Dains 121 3 4 CONTENTS " XXIV. "Amer! Amer ! Amer ! . XXV. McPherson's Telltale Trousers . XXVI. When Glengarry Wrecked the Circus XXVII. -

Winter Newsletter

Volume VI]] No. 4 Brant Historical Society 2001 ISSN 1201-4028 Winter. 2001 i°ehJ:b¥rysa:tf'tR:e#[f:; #::rBrant Historical Society, looks at one of the 2o Photo by Brian Thompson, courtesy Of The Expositor The Brant Historical Society's Wall of Honour stillwishedtofinishthewall. ByRuthLefler He contacted Ralph Cook, a member of the Museum Committee, to do the job. Ralph begantheprojectbutunfortunatelydied. Lastyeartheprojectwasonceagainrevived when Glenn contacted me. I took the plan to contributions. theboardand,withitsblessing,proceeded. The following criteria were established. Thepersonschosenhadtobe: Continued on Page 2 --Giantsintheirownright; -- Outstanding in one field in any two of the following areas - local, provincial, David Glenn Kilmer federal or intemational; L (1914- ) -- Residents at one time of Brantford or A retired high school BrantcountyorsikNations. principal and co- At this time, Glenn was chairman of the founder Of Westfteld Heritage Village, Museum Committee of the Brant Historical Glenn Kilmer initiated Society. He and his committee proceeded to and provided funding choose persons to match the criteria. A list for the Brant was formalized, biographies were written and Historical Society's edited. Before the project was completed, WallofHonour. Glenn left the Society's board of directors but Celebrating 93 years of preserving local history Page 2 B.H.S. Quarterly -Winter, 2ool B.H.S. Quarterly -Winter, 2ool Page 3 TheBrantHistoricalSociety'sWallof Honour Continued from Page 1 Alexander Graham Bell •#ifeS(#, ,qu T**::, , Glenn sent me the list of names offered to (1847-1922) Hiram "rang" Capron (1796-1872) edit the information and provided funding A teacher of the deaf, Alexander President's Reflections for the project. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. -- --- ----- ------ - ~-=---~-=------ - -- ·- - - ' ~ -- ... ~ ·j.."1 .. ' COUNTYOF -- • • • February 2, 2007 I I I FEB O9 2007 Katherine Axford Ontario Heritage Trust Fo1111dation __________ .. _..., __ 10 Adelaide Street East Toronto, Ontario MSC 1J3 Dear Ms. Axford: RE: Bylaws for Designation -Part 4 of the Ontario Heritage Act Please find attached the bylaws and notices for the designation of properties under Part 4 of the Ontario Heritage Act. The properties designated are as follows: I . • 703 Mt. Pleasant Road- Cemetery - fo1·1ner Township of Brantford (Mt. Pleasant) i. .. • 899 Keg Lane - Dwelling - former Township of South Dum fi·ies n,- • Colborne St. E. -Bowstring Bri<;lge-Fo1mer Township ofBrantford Copies of the bylaws have been given to the property owners. We trust this infonnation is satisfactory. Please let me know if additional information is required. Sincerely, • Community & Development Services Department - 66 Grand River St. N., Paris, Ontario, N3L 2M2 (519) 442-6324-(519) 442-3461 (FAX)-mark.pomponi@brantca . - .... ,. " ... ,: ' BY-LAW NUMBER 179-06 - of- THE CORPORATION OF THE COUNTY OF BRANT To designate a property in Part of Lot 5, First Range West of Mount Pleasant Road and all of Registered Plans 45A and 256, geographic Township of Brantford, under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act. -

Mount Pleasant Historical Walking Tour

. Proceed North towards Brantford , Windmill Country Market Brucefield Emily Townsend House (Mount Pleasant Road & Burtch Road) Dr. Emily (657 Mount Pleasant Road) (637 Mount Pleasant Road) ithin decades of its Abraham Cooke, a local “merchant prince,” Eadie/Ellis House & Store - Stowe & built this Georgian/Greek Revival mansion Townsend Mansion Wfounding in 1799, Mount Pleasant was “Site of First Telephone Test” circa 1840. Though now time-worn and (597 Mount Pleasant Road) Dr. Augusta a prosperous and cultured settlement, stripped of elaborate features such as its roof This circa 1848 mansion was built for landowner and (693 Mount Pleasant Road) Stowe Gullen home to men and women who cresting, two storey entry pediment and wrap- carriage-maker Alva Townsend by the same builders around porch, it was the most ostentatious as “Brucefield.” A reflection of the wealth and social distinguished themselves in many United Church Manse Plaque “Willie” Cooke (681 Mount Pleasant Road) (Mount Pleasant house in Mount Pleasant and among the most pretentious ambition of its first owner, this well preserved example fields, as well as flourishing farms, In keeping with their prosperity and large congregation, School, 667 Mount in Upper Canada. It became a great social centre with of elegant Georgian Revival architecture exhibits the inns, mills, schools, a drill hall, and Methodist church leaders of the day wanted a fine, Pleasant Rd.) elaborate parties lasting up to a week. It is notable for a strong horizontal profile and symmetrical arrangement visit in 1846 by Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada commercial establishments. substantial manse to accompany their new church Described in her of windows and doors characteristic of the style. -

Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, Friday, August 23Rd to Saturday

IOCUE 4 PR ldudincj SPORTS Activitie* T c £<fAUG.23toSEPT 7, 1935 t JfcO^V*57 INCLUSIVE »">'jnIW l'17' '.vir^diii IBITION TORONTO The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION o/CANADIANA TORONTO MONTREAL REGIXA HALIFAX PLAN OF GROUNDS AND BUILDINGS CANADIAN NATIONAL EXHIBITION "Be Foot Happy" World's Famous Hot Pavements Athletes Use Long Walks Hard Floors are unkind to Your Feet OLYMPEME Not an the Antiseptic Lihimekt Olympene is kind Ordinary Liniment An Antiseptic Liniment Recommended Especia lly OSCAR ROETTGER, Player Manager, Montreal Royal Baseball. for Athlete's Foot. The Athlete's Liniment. JIM WEAVER, Pitcher, Newark Bears Baseball. For Soreness, Stiffness of Muscles and Joints- . ' W. J " Bill ' O'BRIEN, Montreal Maroons, Montreal. Strains and Sprains- RUTH DOWNING, Toronto. Abscesses, Boils, Pimples and Sores. "Torchy" Vancouver, Six Day Bicycle Cuts and Bruises. PEDEN, Rider. Nervousness and Sleeplessness. BERNARD STUBECKE, Germany, Six Day Bicycle Head Colds, Catarrh and Hay Fever- Rider. RUTH DOWNING Corns, Bunions, Sore or Swollen Feet- FRED BULLIVENT, Head Trainer, Six Day Bicycle Toronto's Sweetheart of the Swim Riders. Sunburn, Poison Ivy, Insect Bites Says Use JIM McMILLEN, Wrestler, Vice-President, Chicago Dandruff. Bears. GEORGE "Todger" ANDERSON, Hamilton, Manufactured by OLYMPENE Assoc. -Coach, Hamilton Olympic Club. NORTHROP & LYMAN CO., LIMITED OLYMPEME Trainer, Bert Pearson, Sprinter. TORONTO ONTARIO the Antiseptic Liniment Established 1854 the Antiseptic Lininent Canadian "National Exhibition :@#^: Fifty-Seventh Annual -

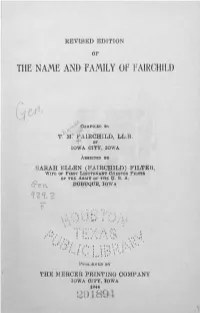

The Name and Family of Fairchild

REVISED EDITION OF THE NAME AND FAMILY OF FAIRCHILD tA «/-- .COMPILED BY TM.'FAIRCHILD, LL.B. OP ' IOWA CITY, IOWA ASSISTED BY SARAH ELLEN (FAIRCHILD) FILTER, WIPE OP FIRST LIEUTENANT CHESTER FILTER OP THE ARMY OP THE U. S. A. DUBUQUE, IOWA mz I * r • • * • • » < • • PUBLISHED BY THE MERCER PRINTING COMPANY IOWA CITY, IOWA 1944 201894 INDEX PART ONE Page Chapter I—The Name of Fairchild Was Derived From the Scotch Name of Fairbairn 5 Chapter II—Miscellaneous Information Regarding Mem bers of the Fairchild Family 10 Chapter III—The Heads of Families in the United States by the Name of Fairchild as Recorded by the First Census of the United States in 1790 50 Chapter IV—'Copy of the Fairchild Manuscript of the Media Research Bureau of Washington .... 54 Chapter V—Copy of the Orcutt Genealogy of the Ameri can Fairchilds for the First Four Generations After the Founding of Stratford and Settlement There in 1639 . 57 Chapter VI—The Second Generation of the American Fairchilds After Founding Stratford, Connecticut . 67 Chapter VII—The Third Generation of the American Fairchilds 71 Chapter VIII—The Fourth Generation of the American Fairchilds • 79 Chapter IX—The Extended Line of Samuel Fairchild, 3rd, and Mary (Curtiss) Fairchild, and the Fairchild Garden in Connecticut 86 Chapter X—The Lines of Descent of David Sturges Fair- child of Clinton, Iowa, and of Eli Wheeler Fairchild of Monticello, New York 95 Chapter XI—The Descendants of Moses Fairchild and Susanna (Bosworth) Fairchild, Early Settlers in the Berkshire Hills in Western Massachusetts, -

NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES Ontario Region NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES Ontario Region Published Under the Authority of the Minister of the Environment Ottawa 1980

Parks Pares Canada Canada NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES Ontario Region NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES Ontario Region Published under the authority of the Minister of the Environment Ottawa 1980 QS-C066-000-BB-A1 © Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1980 Design & Illustrations: Ludvic Saleh, Ottawa INTRODUCTION One of the most effective ways to stimulate popular interest and understanding of Canadian history is to focus attention to those specific locations most directly associated with our history. Since 1922, the Federal government has erected plaques and monuments on the recommendation of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada to commemorate persons, places or events which are of national historic signifi cance. Locations where such commemorations take place are called national historic sites. There are now almost 800 of these sites in Canada, of which more than 200 are in Ontario. This booklet is intended to introduce the reader to those elements of Canadian national historical heritage singled out for commemoration in Ontario. For your convenience, the sites are listed alphabetically as well as by County. iv BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Historic Sites and Monuments proposals. Board of Canada is an advisory body to The Board is assisted by Parks Canada the Minister responsible for Parks through studies of broad historical Canada and acts as an "Independent themes and research on specific per Jury" in determining whether persons, sons, places or events. In addition, places or events, are of national historic Parks Canada will co-operate with local, or architectural importance. provincial and territorial governments It is normally comprised of 17 members: and other interested groups, including 14 representatives from the 10 provinces local historical societies, in making and two territories (2 each from Ontario arrangements for formal ceremonies to and Quebec and one each from the re unveil a plaque or monument. -

ONTARIO (Canada) Pagina 1 Di 3 ONTARIO Denominato Dal Lago Ontario, Che Prese Il Suo Nome Da Un Linguaggio Nativo Americano

ONTARIO (Canada) ONTARIO Denominato dal Lago Ontario, che prese il suo nome da un linguaggio nativo americano, derivante da onitariio=lago bellissimo, oppure kanadario=bellissimo, oppure ancora dall’urone ontare=lago. A FRANCIA 1604-1763 A GB 1763-1867 - Parte del Quebec 1763-1791 - Come Upper Canada=Canada Superiore=Alto Canada 24/08/1791-23/07/1840 (effettivamente dal 26/12/1791) - Come Canada Ovest=West Canada 23/07/1840-01/07/1867 (effettivo dal 5/02/1841) (unito al Canada Est nella PROVINCIA DEL CANADA) - Garantito Responsabilità di Governo 11/03/1848-1867 PROVINCIA 1/07/1867- Luogotenenti-Governatori GB 08/07/1792-10/04/1796 John GRAVES SIMCOE (1752+1806) 20/07/1796-17/08/1799 Peter RUSSELL (f.f.)(1733+1808) 17/08/1799-11/09/1805 Peter HUNTER (1746+1805) 11/09/1805-25/08/1806 Alexander GRANT (f.f.)(1734+1813) 25/08/1806-09/10/1811 Francis GORE (1°)(1769+1852) 09/10/1811-13/10/1812 Sir Isaac BROCK (f.f.)(1769+1812) 13/10/1812-19/06/1813 Sir Roger HALE SHEAFFE (f.f.)(1763+1851) 19/06/1813-13/12/1813 Francis DE ROTTENBURG, BARON DE ROTTENBURG (f.f.) (1757+1832) 13/12/1813-25/04/1815 Sir Gordon DRUMMOND (f.f.)(1771+1854) 25/04/1815-01/07/1815 Sir George MURRAY (Provvisorio)(1772-1846) 01/07/1815-21/09/1815 Sir Frederick PHILIPSE ROBINSON (Provvisorio)(1763+1852) 21/09/1815-06/01/1817 Francis GORE (2°) 11/06/1817-13/08/1818 Samuel SMITH (f.f.)(1756+1826) 13/08/1818-23/08/1828 Sir Peregrine MAITLAND (1777+1854) 04/11/1828-26/01/1836 Sir John COLBORNE (1778+1863) 26/01/1836-23/03/1838 Sir Francis BOND HEAD (1793+1875) 05/12/1837-07/12/1837 -

How Forests and Forest Management Messaging Was Disseminated in Governmental Promotional Material in Ontario, 1800–1959

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations from 2009 2020 How forests and forest management messaging was disseminated in governmental promotional material in Ontario, 1800–1959 Lino, Amanda A. http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/4671 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons HOW FORESTS AND FOREST MANAGEMENT MESSAGING WAS DISSEMINATED IN GOVERNMENTAL PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL IN ONTARIO, 1800–1959 by Amanda A. Lino A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forest Sciences Lakehead University Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada 15 June 2020 Copyright © Amanda Ann Lino, 2020 LIBRARY RIGHTS STATEMENT In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, I agree that the University will make it freely available for inspection. This dissertation is made available by my authority solely for the purpose of private study and research. In addition to this statement, Lakehead University, Faculty of Graduate Studies has forms bearing my signature: Licence to the University, and Non-Exclusive Licence to Reproduce Theses. Signature: Date: 29 April 2020 A CAUTION TO THE READER This PhD dissertation has been through a semi-formal process of review and comment by at least two faculty members. It is made available for loan by the Faculty of Natural Resources Management for the purpose of advancing practice and scholarship. The reader should be aware that opinions and conclusions expressed in this document are those of the student and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the dissertation supervisor, the faculty or Lakehead University. -

OCTOBER 2020 BRANTFORD | BRANT SIX NATIONS FREE EVENT GUIDE PAGE 5 Brantfordbrantford Farmers’Farmers’ Marketmarket Copescopes Withwith Covidcovid

OCTOBER 2020 BRANTFORD | BRANT SIX NATIONS FREE EVENT GUIDE PAGE 5 BrantfordBrantford Farmers’Farmers’ MarketMarket copescopes withwith CovidCovid OUR MEMBERS SHOW STORIES OF HOW THEIR INGENUITY, PERSEVERANCE, AND SUPPORT FROM THE COMMUNITY HELPED THEM TO SURVIVE THE PANDEMIC A time to discover Ontario Public Library Week Oct. 18-24 STORY PAGE 3 2 Entertainment & Community Guide COVID-19 PRECAUTIONS In light of the Pandemic and to help reduce touch points, please follow these guidelines when picking up your copy of BScene! • Take your copy when you’re about to leave the store • Try not to handle other papers OCT. 2020 Vol. 7, Edition 1 • Please Do Not put papers back in the pile (take it home or recycle it when you’re finished) • And as always, keep washing your hands and wearing your masks! BScene is a local Entertainment & Community Guide, showcasing the #BRANTastic features of Brantford, Brant and Six Nations through engaging content and with the Best Event Guide in our community. BScene is distributed free, every month through BE SEEN WITH key community partners throughout Brantford, INSIDE Brant and Six Nations. BScene has a local network of over 500 distribution points including local this issue advertisers, retail outlets, dining establishments, and community centres. For a complete list, Brantford Farmers' Market 3 BSCENE please visit bscene.ca As a community paper and forum for sharing Community News & Media Releases 4 - 5 thoughts and experiences, the views expressed in the magazine are not necessarily those of the OCTOBER 2020 EVENT GUIDE 5 Publisher, Editor, other contributors, advertisers BSCENE AROUND or distributors unless otherwise stated.