"So, You're from Brixton?" Towards a Social Psychology of Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Crystal Palace – Brixton – Trafalgar Square

3 CrystalPalace–Brixton–TrafalgarSquare 3 Mondays to Fridays CrystalPalaceBusStation 0555 0747 0847 1543 1859 1909 1919 1931 1943 1955 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 0603 Then 0758 Then 0900 Then 1552 Then 1907 1917 1927 1939 1951 2003 HerneHillStationDulwichRoad 0611 about 0809 about 0913 about 1601 about 1915 1925 1935 1947 1959 2010 BrixtonStation 0619 every7-8 0821 every8-9 0924 every8 1611 every8-9 1924 1934 1944 1956 2008 2018 KenningtonChurch(forOvalStation) 0627 minutes 0831 minutes 0934 minutes 1621 minutes 1934 1944 1954 2006 2017 2027 MillbankLambethBridge 0637 until 0850 until 0945 until 1632 until 1943 1953 2003 2015 2026 2036 TrafalgarSquareCockspurStreet 0644 0901 0957 1644 1952 2002 2010 2022 2033 2043 CrystalPalaceBusStation 2007 2131 2143 2155 2207 2219 2231 2243 2255 2310 2325 2340 2355 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 2014 Then 2138 2150 2202 2213 2225 2237 2249 2301 2316 2331 2346 0001 HerneHillStationDulwichRoad 2021 every12 2145 2157 2208 2219 2231 2243 2255 2307 2322 2337 2352 0007 BrixtonStation 2028 minutes 2152 2204 2214 2225 2237 2249 2301 2313 2328 2343 2358 0013 KenningtonChurch(forOvalStation) 2037 until 2201 2212 2222 2233 2245 2257 2307 2319 2334 2349 0004 0019 MillbankLambethBridge 2046 2210 2221 2231 2242 2254 2306 2316 2328 2343 2358 0013 0028 TrafalgarSquareCockspurStreet 2053 2217 2228 2238 2249 2301 2313 2323 2335 2350 0005 0020 0035 3 Saturdays (also Good Friday) CrystalPalaceBusStation 0555 0610 0625 0640 0655 0710 0725 0740 0752 0804 0814 0824 0832 0840 0848 0855 0902 0910 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 0602 0617 0632 -

Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold

Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold Purpose built apartment Modern family bathroom suite Two double bedrooms Large living and entertaining area Neutral decor Separate W/C Bright and spacious throughout Private balcony Contemporary fitted kitchen Parking available 2, Lansdowne Road, Croydon, London, CR9 2ER Tel: 0330 043 0002 Email: [email protected] Web: www.truuli.co.uk Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold **Vendor Comments** "We really love this flat. The neighbourhood is quiet, despite being near so many amenities. Since we bought it five years ago we’ve put in a new kitchen & bathroom; painted & wallpapered all the walls and carpeted & tiled every floor. We left here to get married and brought our baby home here. We hosted our parents for Christmas dinner and had sun-downers on the balcony in the summer. The location is ideal, near Tulse Hill, Herne Hill and West Norwood stations. We’re 20 minutes from central London via Tulse Hill station or 35 minutes via bus and Brixton tube station. We get to park outside our flat permitting and cost free too, which is a plus. We know and talk to all our neighbours in our small block and 3 years ago the residents association was setup. There’s also a community hall for hire which is very nearby where we hosted our baby's christening party. We’re a 5 minute walk from Brockwell park with its picnic spots, lido, miniature railway and park runs. There’s the Tulse Hill Hotel for lunch or a drink and two breweries next to the park (Bullfinch & Canopy). -

Brand New 19,000 Sq Ft Grade a Office

BRAND NEW 19,000 SQ FT GRADE A OFFICE 330 CLAPHAM ROAD•SW9 If I were you... I wouldn’t settle for anything less than brand new Let me introduce you to LUMA. 19,000 sq ft of brand new premium office space conveniently located just a short stroll from Stockwell and Clapham North underground stations. If I were you, I know what I would do... 330 Clapham Road SW9 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New 330 Clapham Road SW9 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New I’d like to see my business in a new light Up to 19,000 sq ft of Grade A office accommodation is available from lower ground to the 5th floor, benefiting from excellent views and full height glazing. 02 03 A D R O N D E E A M I L 5 1 Holborn 1 A E D G W £80 per sq ft A R E R O A City of London D Soho A 1 3 C O M M E Poplar R C I A L R City O A D D £80 per sq ft A O White City R A 1 2 0 3 T H E H I G H W A Y Mayfair E Midtown G D Hyde I R Park B £80 per sq ft R E W O T 0 0 A 3 Holland 1 3 A 2 0 Park St James Waterloo Park Southwark D £71 per sq ft A O R L £80 per sq ft L E W M O R Westminster C E S T A 4 W O A D per sq ft W E S T C R O M W E L L R £75 Vauxhall Belgravia £55 per sq ft D V 330 Clapham Road SW9 A R U Isle of Dogs Pimlico X K H R A L A L P B R N I A D O 2 G E T N G E W N I C auxa R D N O R O A S O R N S S V E N E R R O K O G A 2 1 2 D A 3 3 A B Oa A A 2 T 0 Oval T 3 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New Battersea E R S S Battersea E L £50 per sq ft A Park £50 per sq ft A M A Fulham B 2 R B 0 D D E 2 I A D O T A C G R H A K O M E R R A R B P E D R A R N W D E Peckham R S E E T O L A T L B T 5 N E 2 0 X W R O 3 I A D A R B D per Camberwell I’d want my business A 3 O £45 sq ft 2 R A A tocwe 3 andswort S located in Central London’s 2 R 2 A oad 0 D E Louborou E most cost effective C L unction S 6 P 1 E 2 T R 3 A L U C Capam R I H C H T A U O S 5 R i t. -

Visiting Artists

Welcome Pack VISITING ARTISTS Hello! Streatham Space Project is a new live performance venue, purpose-built for Streatham and Greater London. The venue includes a 123 seat fully-flexible auditorium for theatre, music, comedy, dance and family friendly activities; a rehearsal room for dance classes, yoga, theatre workshops as well as plenty more; and a buzzing café and bar area. Streatham Space Project is an experiment in what an arts space can do for a neighbourhood like Streatham and the wider London community. Enclosed you will find information about Streatham Space Project including travel, contact and access information. We look forward to welcoming you soon! X The SSP Team CONTACT INFO Executive Director Lucy Knight – [email protected] Venue and Operations Manager Lexie McDougall – [email protected] Marketing Ella Kilford – [email protected] Production Manager [email protected] 1 GETTING HERE Address: Streatham Space Project Sternhold Avenue London, SW2 4PA TRANSPORT Tube/Bus The nearest tube stations are Brixton, Balham and Tooting Bec. The nearest bus stop is Streatham Hill/Streatham Hill Station. From Brixton busses 109, 118, 133, 159, 250 and 333 run towards Streatham Hill Station From Tooting Bec bus route 319 runs towards Streatham Hill Station From Balham bus route 255 runs towards Streatham Hill Station Rail Streatham Hill Station is a 1-minute walk from Streatham Space Project and runs towards London Bridge and Victoria Streatham Station is 15-minute walk to Streatham Space Project along Streatham High Road Bike There are bike racks along Streatham High Road, there is currently no bike parking at Streatham Space Station and bikes should not be brought into the building Car Parking Streatham Space Project has no parking spaces available on site. -

Low Cost/No Cost Family Fun in London Please Look at Organisations’ Websites to Double Check Times and Arrangements

Low Cost/No Cost Family Fun in London Please look at organisations’ websites to double check times and arrangements London Open House weekend 22 and 23 September – locations across London Open House London is the world’s largest architectural festival, giving FREE public access to 800+ buildings, walks, talks and tours over one weekend in September each year. To find out what’s happening visit: www.openhouselondon.org.uk Examples include: Kia Oval (Surrey Cricket Ground), SE11 5SS Saturday 21 September 10am – 5pm. The Edible Bus Stop Studio, Arch 511, Ridgway Road, SW9 7EX Sunday 22 September 2 – 6pm A former mechanics garage, refurbished, utilising reclaimed and recycled materials to create a design studio and workshop. Brixton Windmill, Blenheim Gardens, Brixton Hill SW2 5EU 21 and 22 September 1 – 4.30pm The only surviving windmill in inner London, built in 1816. Guided tours of the exterior and first two floors, bookable through the website. Please note that the flors beyond the first floor are accessed by steep ladder-stairs, children must be over 1.2m in height. Lambeth Tower Hall 21 and 22 September - 10am – 5pm Warwick & Austin Hall Landmark Edwardian Baroque style town hall in red brick and Portland stone. striking new atrium, reception and courtyard space along with grand marble lined staircase and ornate council chamber. Grade 2 listed. National Theatre, Upper Ground, South Bank, SE1 9PX 21 September 10am -5pm and 22 September 12.15-5pm Housing one of the world’s most important producing theatres! The building is a key work in British Modernism with three theatres, designed with workshops and theatre-making all on site. -

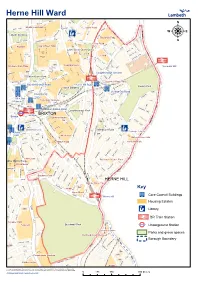

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C B G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S a YN T OST N O

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C b G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S A YN T OST N O M R S A T M T E L R M A PL E A W R R L N O Myatts Field South R S O K O OAD RT A T Paulet Road T E R R U C B A D E P N N N R T E LO C L A C R L L E D T D R A T S R U R E K E R B I L O E B N E H PE A L NFO U A L C R D M W D A S D T T A P A Y N A R A W Slade Gardens R O N V E C O E A K R K D L A D P H C L Thorlands TMO A RO R AD B UGH ORD O EET RO LILF ROA U TR HBO D R S G K RT OU E SA L M B T N C O M R S D I A B A A N L U L O E SPICE E Lilford Road D R R R D R : T E A Y E T D O C R CLOSE E A R R N O O Angell Town TMO Sch R S A S T M C A Robsart Y L O T E A E A I V D R L N D R W E C F A R O E R E O L V T A I L R T O F L N D A Elam Street Open Space D N E L R V E R AC O A PL O FERREY O R B D H A U O R N A S U D TO MEWS G A I AY T Sch N D L O D A H I C WYNNE T D L K Hertford E B A W N O W O E E V R L I N RD SERENADERS Lilford R GR L O A R N A Y E P N O T A MEWS E M N A O R S A E U O W D S S U K S W R M T I S O C N T R G E A G K L X B O T L R A H E W K ROAD R A P U A K R O D R O E S L A DN O U D D G F R O O A D B R V L A Sch U A U X G Loughborough O H H D R R A Stockwell Park TMO AN D D N A GE F S L O Denmark Hill L E T L S R A R O T T E Y E L L T C H RK R E E A A O Y S R OAD L P A B VILLA R EL S D R G O G N M D D U N E M R Sch A RD A N D R A E G L R S D W L L R A O Y S L SE M A Loughborough Junction UM B S E R E F T D D N Y N W E R C F E R C O I S A H D E E I A L R M T C C D D T S U W B Max Roach Park R R R I O G N A P D A I D F G S T 'S O D A N N H E S -

433 Coldharbour Lane, Brixton, London Sw9 8Ln Retail to Rent | 388 Sq Ft | £18,000 Per Annum

433 COLDHARBOUR LANE, BRIXTON, LONDON SW9 8LN RETAIL TO RENT | 388 SQ FT | £18,000 PER ANNUM LONDON'S EXPERT COMMERCIAL UNION STREET PARTNERS PROPERTY ADVISORS SOUTH OF THE RIVER 10 STONEY STREET UNIONSTREETPARTNERS.CO.UK LONDON SE1 9AD T 020 3757 7777 433 COLDHARBOUR LANE, BRIXTON, LONDON SW9 8LN A1 RETAIL UNIT TO LET 388 SQ FT | £18,000 PER ANNUM DESCRIPTION AMENITIES The property is located in a prominent position on the southern side Prominent unit in central Brixton of Coldharbour Lane, half way between the junctions with Atlantic Close to Underground and train stations Road and Brixton Road and directly opposite Brixton Market. Both Economical space with character frontage Brixton Underground and Railway stations are within a 3 minute Opposite Brixton Market walk of the property and the surrounding occupiers include a variety of multiple and independent bars, restaurants and retail outlets. TERMS The demised premises comprise a self-contained ground floor retail unit, partially fitted and with a character shop front. The premises RENT RATES S/C are available by way of a new, full repairing and insuring lease on Est. £6,720 per £18,000 per annum TBC terms to be agreed. annum New lease available direct from the landlord AVAILABILITY FLOOR SIZE (SQ FT) AVAILABILITY Unit 301 Available TOTAL 301 GET IN TOUCH CHARLIE COLLINS NEIL DAVIES Union Street Partners Union Street Partners 020 3757 8570 020 7855 3595 [email protected] [email protected] SUBJECT TO CONTRACT. UNION STREET PARTNERS FOR THEMSELVES AND THE VENDOR OF THIS PROPERTY GIVE NOTICE THAT THESE PARTICULARS DO NOT FORM, OR FORM PART OF, ANY OFFER OR CONTRACT. -

Trams in Brixton 1870 - 1951

TRAMS IN BRIXTON 1870 - 1951 Horse Trams Two Acts of Parliament, passed in 1869 and 1870, empowered the Metropolitan Street Tramways Company to construct tramways from the Lambeth end of Westminster Bridge to Brixton and to Clapham. The company got to work quickly; they lost no time in laying down double tracks with rails level with the surface of the road. 2 May 1870 was an important day in Brixton's history. It was the day when the first authorised tramcars operated in London. 1 The new trams ran that day from the Horns Tavern in Kennington Road and along Brixton Road as far as its junction with Stockwell Road. The smart blue tramcars were hauled by two horses. Cars seated 22 persons inside and 24 on the open top deck. The passengers inside sat on red velvet cushions. For top deck passengers were two wooden benches running the length of the tram; these passengers faced outwards. Trams ran every five minutes. The normal fare was a penny a mile but Parliament had required special trams to be run for workmen in the morning and evenings at a halfpenny a mile.2 As soon as the 1870 Act was passed more track laying was rushed on with, and by the end of 1870 trams were in service from the Lambeth end of Westminster Bridge to St Matthew's church, Brixton, and another line ran along Clapham Road to the Swan at Stockwell. During 1871 tramcars had reached the Plough at Clapham, and the Brixton Line had been extended to the junction of Brixton Water Lane. -

Additional Supporting Information from Objectors

ADDITIONAL SUPPORTING INFORMATION FROM OBJECTORS BRIXTON SPD Adopted June 2013 Coproduction: a summary of the messages that emerged from workshops and market stall events during June, July and August 2012. PEOPLE LOVE BRIXTON – celebrate the very special things Brixton already has SUPPORTING A DIVERSE ECONOMY – support local employment through a range of business types and sizes, with specific support for start ups and independents IMPORTANCE OF SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE – improve local environments and open spaces, ensure quality leisure and cultural facilities, support local schools PROVIDING HOMES FOR ALL – provide for local housing need, balance of social housing and private units IMPROVING ACCESS AND CONNECTIONS – enhance existing connections, address barriers and improving parking and cycling RESPECTING LOCAL CHARACTER – creating a great place to live, protecting Brixton’s built heritage, bringing upper floors back into use KEEPING IT SAFE – simple measures, comfortable environments, a range of activities for all ages SUSTAINABLE BRIXTON – promoting One Planet Living principles, supporting local initiatives and delivering economic, social and environmental sustainability USE EVERY SPACE – ensuring land and buildings are used efficiently, bringing under used upper floors back into active use MAKING IT HAPPEN – balancing the needs of existing and new residents and using Council-owned assets to support opportunities CSONTENT 1 Introduction AND context 1 4 AREA strategies 37 1.1 Introduction and Vision 1 4.1 Introduction 37 1.2 Purpose of -

Diverse Effects, Strategies and Perspectives Among Small Migrant Businesses in Gentrifying Brixton

The multifaceted face of neighbourhood change; diverse effects, strategies and perspectives among small migrant businesses in gentrifying Brixton Maarten Kaptein, 4149319 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. Ilse van Liempt Word count: 12295 Abstract International migration has been growing and diversifying in recent decades impacting both sending and receiving societies. Among migrants self-employment is a common source of income which is visible in the great number of ethnic businesses in major cities. Gentrification, tourism and place-consumption has been altering the residential and commercial landscapes of cities, not in the least ethnic neighbourhoods. Theory on migrant (or ethnic minority) business considers entrepreneurship to be shaped by the interaction between personal characteristics and well as the institutional and socio-economic context. Whereas many studies on migrant business focus on ethnic groups, this study investigates migrant businesses from various backgrounds in a particular neighbourhood. This approach sheds light on the various effects of neighbourhood change among a variety of migrant businesses. The aim of this study is to investigate the various effects of neighbourhood change on migrant businesses, the adaptive strategies employed by migrant entrepreneurs and the implications of these changes for the neighbourhood in Brixton, London. The data was collected using qualitative methods. Among the various participants neighbourhood change proves to be a challenge as well as a potential opportunity. While some business transform to more mainstream types of business, the future of many of the more traditional ethnic businesses is precarious. Keywords: Migrant entrepreneurship, mixed embeddedness, adaptive strategies, urban transformations, gentrification Introduction International migration has been growing and diversifying in recent decades impacting both sending and receiving societies. -

Membership & Order Form

THE BRIXTON SOCIETY : MEMBERSHIP & ORDER FORM PUBLICATION Registered Charity No.: 1058103 Prices as at: March 2018 NO. PRICE AMOUNT BOOKS REPRESENTING BRIXTON – story of Brixton’s MPs 2015 A5 26pp illustrated £2.50 BRIXTON MARKETS – A HERITAGE WALK: a guide to the Markets 2011 A5 22pp illustrated £2.00 BRIXTON AND STOCKWELL IN THE (19th century) MIRROR – 2011 A4 illustrated booklet 12pp £1.20 WINDRUSH SQUARE: a guide to the Square and its surroundings 2011 20pp A5 with illustrations £1.00 THE BRIXTON SYNAGOGUE: 20pp A5 with illustrations £2.49 BLACK BRITISH – A CELEBRATION:. 2007, 104pp A5 with illustrations – special offer £2.00 A BRIXTON BOY IN WORLD WAR II- an experience in & out of London. 2006, 20pp A5 illustrated £2.49 BRIXTON HERITAGE TRAILS: six walks around Brixton and Stockwell.2001, 88pp with illustrations £1.50 BRIXTON THE STORY OF A NAME: 1991, reset and reprinted 1998, 17pp £1.00 EFFRA: LAMBETH’S UNDERGROUND RIVER: the story of the Effra. 1993, reprinted 2011, 28pp £1.50 BRIXTON MEMORIES: collected oral, local history. 1994, 52pp A4, with 16 illustrations, £4.99 A HISTORY OF BRIXTON by Alan Piper. 1996, 104pp with many illustrations, reprinted 2008 £9.99 “BRIXTON abridged” monographs Trams in Brixton 1870-1951: 6pp, A4 £0.50 Stockwell Congregational School: 4pp, A4 £0.30 “Most Agreeable Suburb”: Brixton in the 1840s: 2pp, A4 £0.15 Brixton Memories of Dora Tack: 4pp, A4 £0.30 “Sketches of Living London. The Brixton Road - 10 September 1896”: 2pp, A4 £0.15 A Jamaican Girlhood: 6pp, A4 £0.50 EDWARDIAN POSTCARDS reprinted by the Society – All Postcards 50p each or any 5 for £2 BX9 - Brixton Road/corner of Stockwell Road - busy street scene BX10 - Brixton Road/Crown & Anchor pub BX11 - Brixton Road/Brixton Independent Church - early motor buses BX12 - Effra Road/Brixton Hill - St Matthew’s & the Budd Memorial BX13 - The Palladium (now The Fridge) & The Town Hall BX14 – Greeting from Brixton – 5 views inc. -

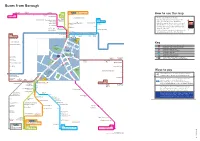

Buses from Borough

Buses from Borough Hoxton Newington Mildmay NewingtonGreen MildmayPark BaringHoxton Street 35 from stops D, G, P Green Park Baring Street 133 35 from stops D, G, P 133 Shoreditch 21 21 Southgate from stops Shoreditch 21 21 SouthgateRoad from stops from stops F, G, M Road New Road North C, G, P from stops F, G, M New Road North C, G, P Liverpool SHOREDITCH LiverpoolStreet SHOREDITCH HOXTON Moorelds Eye Hospital Street 343 HOXTON Moorelds Eye Hospital Bus Station Old Street Bus Station from stops D, G, P Old Street from stops D, G, P Liverpool Street ALDGATE Aldgate Finsbury Square 133 BishopsgateLiverpool Street ALDGATE Aldgate Finsbury Square 133 Bishopsgate Bus Station Moorgate Bus Station Moorgate 21 35 21 35 343 Bishopsgate 343 CITY OF Bishopsgate CITY OF Bank Tower Gateway LONDON Bank Tower Gateway LONDON Monument Monument River Thames River Thames London Bridge C10 London Bridge London 343 Tooley City Tower C10 LondonBridge 343 TooleyStreet CityHall BridgeTower from stops A, B, J 21 35 Bridge Street Hall Bridge from stops A, B, J 13321 343 35 Victoria 133 343 Victoria King’s King’s ` NEW College ` NEW CollegeLondon VICTORIA COMENLondon VICTORIA COMEN S MERMA STREET Victoria Coach Station MERMA TREET Victoria Coach Station Footpath CH T Footpath CHAP I ET T A EL CT D COEE P I R ET EL CT D COE a T EE R a ST U Little Dorrit RE RT S U Little Dorrit TR S RT Park I ST S Park I M S Library N H MA Library NN GH AR I EN S G R HI A TE SH NGEL PL A T H L H ANGEL PL ALSE H SEA R GH A O UG ROAD St.