Human Rights in Sri Lanka, an Update 2 News from Asia Watch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pattu Central-Chenkalady, Eravur Town

Invitation for Bids (IFB) High Commission of India Grant Number: Col/DC/228/01/2018 Grant Name: Construction of 3,200 Sanitary Units, to enhance the Public health in Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka Estimated Cost Contract Required Bid No Description of Work Excluding Period Grade VAT (SLR in millions) Sri Lankan Bidder: C4 or above/ equivalent Construction of 3,200 (Building) Col/DC/228/01/ Sanitary Units, to enhance the 300 09 months Indian 2018 Public health in Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka Bidder: Class-IV or above/ equivalent (Building) 1. Government of India has approved a Grant for Construction of 3,200 Sanitary Units, to enhance the Public health in Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka based on the proposal submitted by Ministry of Mahaweli, Agriculture, Irrigation and Rural Development, Sri Lanka with the objective of providing a solution for the scarcity of sanitary facilities in Batticaloa District. 2. The Government of India invites sealed bids from eligible and qualified bidders who had experience in construction of Sanitary units to construct 3200 numbers of Sanitary units , to enhance the public health in Koralai Pattu North- Vaharai, Koralai Pattu Central- Valachchenai, Koralai Pattu West-Oddamawadi, Koralai Pattu-Valachchenai, Koralai Pattu South-Kiran, Eravur Pattu Central-Chenkalady, Eravur Town – Eravur, Manmunei North -barricaloa, Manmunei West -Vavunathivu, Manmunei Pattu -Arayampathi, Kattankudy, Manmunei South West-Paddpali, Manmunei South & eruvil Pattu Kaluwanchikudy and Porativ Pattu-Vellaveli under Six packages. The Construction period is 09 Months. 3. Bidding will be conducted through National Competitive Bidding Procedure – Single Stage – Two envelope bidding procedure. (Single stage Two envelop: Bidder has to submit technical and financial bids and duplicate of it separately in four different sealed envelope). -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

The 35Th Annual Conference on South Asia (2006) Paper Abstracts

35th Conference on South Asia October 20 – 22, 2006 Accardi, Dean Lal Ded: Questioning Identities in Fourteenth Century Kashmir In this paper, I aim to move beyond tropes of communalism and syncretism through nuanced attention to Indian devotional forms and, more specifically, to the life and work of a prominent female saint from fourteenth century Kashmir: Lal Ded. She was witness to a period of great religious fermentation in which various currents of religious thought, particularly Shaiva and Sufi, were in vibrant exchange. This paper examines Lal Ded’s biography and her poetic compositions in order to understand how she navigated among competing traditions to articulate both her religious and her gender identity. By investigating both poetic and hagiographic literatures, I argue that Lal Ded’s negotiation of Shaivism and Sufism should not be read as crudely syncretic, but rather as offering a critical perspective on both devotional traditions. Finally, I also look to the reception history of Lal Ded’s poetry to problematize notions of intended audience and the communal reception of oral literature. Adarkar, Aditya True Vows Gone Awry: Identity and Disguise in the Karna Narrative When read in the context of the other myths in the Mahabharata and in the South Asian tradition, the Karna narrative becomes a reflection on the interdependency of identity and ritual. This paper will focus on how Karna (ironically) negotiates a stable personal identity through, and because of, disguised identities, all the while remaining true to his vows and promises. His narrative reflects on the nature of identity, self-invention, and the ways in which divinities test mortals and the principles that constitute their personal identities. -

Part 5: List of Annexes

PART 5: LIST OF ANNEXES Annex 1: Letter of Endorsement Annex 2: Site Description and Maps Annex 3: Climate change Vulnerability and Adaptation Summary Annex 4: Incremental Cost Analysis Annex 5: Stakeholder Involvement Plan Annex 6: List of contacts Annex 7: Socioeconomic Status Report Annex 8: Monitoring and Evaluation Plan Annex 9: Bibliography Annex 10: Logical Framework Analysis Annex 11: Response to STAP Review Annex 12: Letter of Commitment- Coast Conservation Department Annex 13: Letter of Commitment- Ministry of Environment Annex 14: Letter of Commitment- International Fund for Agricultural Development _________________________________________________________________________________________________51 Tsunami Coastal Restoration in Eastern Sri Lanka Annex 2: Site Description and Maps Preamble The project is designed for the restoration and rehabilitation of coastal ecosystems. The initial emphasis of this five-year project will be on developing a scientifically based, low-cost, community-based approach to rehabilitating key coastal ecosystems at specific sites in the East Coast and facilitating replication of these techniques all along the East Coast (and in due course other tsunami-affected coasts). Three sites representing three major ecosystems – mangroves, coastal lagoons, and sand dunes –have been identified for piloting these themes. The selection was based on outputs from the Threats Analysis and the following criteria. 1. Hotspot analysis: sites where the tsunami effect was severe on the ecosystems and post tsunami reconstructions are in progress, global/national biodiversity importance exist, concentration of various resource users and their high dependency over the available resources exist and user conflicts exist. 2. Accessibility: accessibility by road was a criterion for selecting pilot sites 3. Absence of ongoing management and monitoring projects: sites at which on-going projects have not being considered for selection 4. -

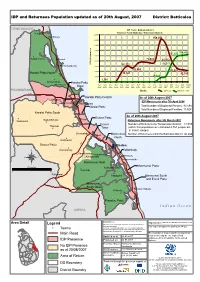

IDP and Returnees Population Updated As of 20Th August, 2007 District: Batticaloa

IDP and Returnees Population updated as of 20th August, 2007 District: Batticaloa TRINCOMALEETRINCOMALEE IDP Trend - Batticaloa District Verugal ! Returnees Trend - Batticaloa / Trincomalee Districts 180,000 Kathiravely ! 159,355 160,000 140,000 120,000 97,405 104,442 ! 100,000 Kaddumurivu ! Vaharai 72,986 80,000 81,312 IDPs/Returnees 60,272 68,971 ! Pannichankerny 60,000 52,685 40,000 51,901 Koralai Pattu North A 1 38,121 42,595 5 20,000 15,524 ! 1,140 Kirimichchai 0 ! Koralai Pattu Marnkerny April May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar April May June July August West 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 POLONNARUWAPOLONNARUWA Months IDP Trend Returnees' Trend A11 Koralai Pattu Central As of 20th August 2007 Vahaneri ! ! IDP Movements after 7th April 2006 Odamavadi Valachchenai ! Koralai Pattu Total Number of Displaced Persons: 42,595 Total Number of Displaced Families: 11,528 Koralai Pattu South As of 20th August 2007 ! ! Eravur Pattu Kudumbimalai Kiran Returnees Movements after 9th March 2007 Vadamunai ! Eravur Number of Returnees to Trincomalee District: 13,589 Tharavai ! Town (within this population an estimated 4,761 people are in transit camps) ! Chenkalady ! Eravur Manmunai Number of Returnees within the Batticaloa District: 90,853 ! A1 North 5 Irralakulam Eravur Pattu A5 Batticaloa ! Pankudavely Kattankudy ! ! Karadiyanaru Vavunathivu ! Kattankudy ! Aythiyamalai ! Arayampathy ® Manmunai West ! Manmunai Pattu Kilometers ! Kokkadicholai Unnichai 020 Pullumalai ! ! Paddipalai -

10Th Session 2009

IS THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY AWARE OF THE GENOCIDE OF TAMILS? APPEAL TO THE UN HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL APPEL À LA PRISE DE CONSCIENCE DU CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L 'H OMME - NATIONS UNIES LLAMADO PARA REACCIÓN URGENTE DEL CONSEJO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS -NACIONES UNIDAS WEBSITE : www.tchr.net 10th session / 10ème session / 10° período de sesiones 02/03/2009 -- 27/03/2009 TAMIL CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS - TCHR CENTRE TAMOUL POUR LES DROITS DE L 'H OMME - CTDH CENTRO TAMIL PARA LOS DERECHOS HUMANOS (E STABLISHED IN 1990) HYPOCRISY OF MAHINDA RAJAPAKSA “T HERE IS NO ETHNIC CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA AS SOME MEDIA MISTAKENLY HIGHLIGHT ” MAHINDA RAJAPAKSA TO THE LOS ANGELES WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL – 28 SEPTEMBER 2007 “Ladies and Gentlemen, our goal remains a negotiated and honourable end to this unfortunate conflict in Sri Lanka. Our goal is to restore democracy and the rule of law to all the people of our country. 54% of Sri Lanka’s Tamil population now lives in areas other than the north and the east of the country, among the Sinhalese and other communities. There is no ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka - as some media mistakenly highlight. Sri Lanka’s security forces are fighting a terrorist group, not a particular community.” “I see no military solution to the conflict. The current military operations are only intended to exert pressure on the LTTE to convince them that terrorism cannot bring them victory.” (Excerpt) http://www.president.gov.lk/speech_latest_28_09_2007.asp * * * * * “....W E ARE EQUALLY COMMITTED TO SEEKING A NEGOTIATED AND SUSTAINABLE SOLUTION TO THE CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA ” MAHINDA RAJAPAKSA TO THE HINDUSTAN TIMES LEADERSHIP SUMMIT AT NEW DELHI ON 13 OCTOBER 2007 “It is necessary for me to repeat here that while my Government remains determined to fight terrorism, we are equally committed to seeking a negotiated and sustainable solution to the conflict in Sri Lanka. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

A Study on Sri Lanka's Readiness to Attract Investors in Aquaculture With

A Study on Sri Lanka’s readiness to attract investors in aquaculture with a focus on marine aquaculture sector Prepared by RR Consult, Commissioned by Norad for the Royal Norwegian Embassy, Colombo, Sri Lanka Sri Lanka’s readiness to attract investors in aquaculture TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 6 Background and scope of study .............................................................................................................. 8 Action plan - main findings and recommendations ................................................................................ 8 Ref. Annex 1: Regulatory, legal and institutional framework conditions related aquaculture ...... 9 Ref. Chapter I: Aquaculture related acts and regulations ............................................................... 9 Ref. Chapter II: Aquaculture policies and strategies ..................................................................... 10 Ref. Chapter III: Aquaculture application procedures ................................................................. 10 Ref. Chapter IV: Discussion on institutional framework related to aquaculture ......................... 11 Ref. Chapter V: Environmental legislation ................................................................................... -

UN-Habitat Implements Disaster Risk Reduction Initiatives in Mannar Town in Sri Lanka's Northern Province

UN‐Habitat Implements Disaster Risk Reduction Initiatives in Mannar Town in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province May 2014, Mannar, Sri Lanka. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN‐Habitat), in collaboration with the Mannar Urban Council, is implementing a number of small scale Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) initiatives to assist communities cope with the adverse impacts of natural disasters through the Disaster Resilient City Development Strategies for four Cities in the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka (Phase II) Project. Funded by the Government of Australia, the project is being implemented by UN‐Habitat in the towns of Mannar, Vavuniya, Mullaitivu and Akkaraipattu in collaboration with the Local Authorities, the Ministry of Disaster Management, and Urban Development Authority (UDA), Sri Lanka Institute of Local Governance (SLILG), Institute for Construction Training and Development (ICTAD) and the University of Moratuwa. Implementing small scale DRR interventions is a key output of the Disaster Resilient Urban Planning and Development Unit that has been established at the Mannar Urban Council. The need for such DRR activities was identified by the project partners as a key priority during the implementation of Phase I during 2012‐2013. As a result, additional funding has been allocated to implement small scale DRR activities in the four cities during the second phase. Small scale infrastructure has been identified by the communities and the LAs to reduce the vulnerability to disasters of settlements and communities. In the Mannar Urban Council area, the infrastructure activities 50 Housing Scheme Road before rehabilitation identified included rehabilitation of two internal roads and laying of Hume pipes and culverts to release storm water from flood‐prone areas. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

Sri Lankan Deportees Allegedly Tortured on Return from the UK and Other Countries All Cases Have Supporting Medical Documentation

Sri Lankan deportees allegedly tortured on return from the UK and other countries All cases have supporting medical documentation I. Cases in which asylum was previously denied in the UK Case 1 PK, a 32-year-old Tamil man from Jaffna, was among 24 Tamils deported to Sri Lanka by the UK Border Agency on 16 June 2011. PK told Human Rights Watch he had been previously arrested by the Sri Lankan police and remanded in custody by the Colombo Magistrate court. While in detention he was seen by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on three occasions. PK had fled Sri Lanka in 2004 following the split of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) with its Eastern Commander, Colonel Karuna, and sought asylum in the UK in April 2005. PK told Human Rights Watch that he and the other deportees were taken aside for questioning by officials who introduced themselves as CID (Criminal Investigation Department) soon after they arrived at Katunayake International Airport in Negombo, outside of Colombo. PK said the officials took all his details down and allowed him to leave the airport. PK said: My aunt warned me not to go to Jaffna through Vanni as I did not have my national ID card. I stayed in Negombo with her. While I was in Negambo, the authorities went to my address in Jaffna, looking for me. However after about six months, I decided to go to Jaffna. On 10 December 2011 on my way, I was stopped at the Omanthai checkpoint [along the north-south A9 highway] by the authorities. -

Environmental Screening Peport

Environmental Screening Report Construction of Pocket Parks at Beach Road, Russell Square & Rasaavinthoddam at Jaffna Project Management Unit Strategic Cities Development Project Ministry of Megapolis & Western Development July 2019 1 Table of Contents 1. Project Identification 03 2. Project Location 03 3. Project Justification 03 4. Project Description 09 5. Description of the Existing Environment 16 6. Public Consultation 18 7. Environmental Effects and Mitigation Measures 19 7a. Screening for Potential Environmental Impacts 19 7b. Environmental Management Plan 23 8. Cost of Mitigation 36 9. Conclusion and Screening Decision 37 10. EMP implementation responsibilities and costs 38 11. Screening Decision Recommendation 38 12. Details of Persons Responsible for the Environmental Screening 39 Annexes Annex 1: Project Location Map Annex 2: Physiographic Locations of Jaffna Peninsula Annex 3: Geology and Soil Map of the Project Area Annex 4: Map of wetlands in Jaffna Peninsula Annex 5: Geology and conditions of ground water in Jaffna Peninsula Annex 6: Design Layouts Annex 7: Summary of Procedures to obtain Mining License for Borrow Pit & Quarry Operation and Management Guidelines Annex 8: Waste Management General Guidelines Annex 9: Environmental Pollution Control Standards Annex 10: Factory Ordinance and ILO Guidelines Annex 11: Chance Find Procedures Annex 12: Terms of Reference for Recruitment of Safeguard Officer 2 Strategic Cities Development Project Environmental Screening Report 1. Project Identification Project Title Construction