Chatwin Final 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Romance O Vice-Rei De Uidá, De Bruce Chatwin, E O Filmecobra Verde, De Werner Herzog: Um Estudo Da Transposição Midiática

O romance O vice-rei de Uidá, de Bruce Chatwin, e o filmeCobra verde, de Werner Herzog: um estudo da transposição midiática Maria Cristina Cardoso Ribas Mariana Castro de Alencar (...) uma nuvem sem contornos passa acima dele mudando constantemente de forma. Ora, o que se pode conhecer de uma nuvem, senão adivinhando-a sem nunca apreendê-la inteiramente? Georges Didi-Huberman Introdução – Falando de obras pouco difundidas quase desconhecido romance O Vice-Rei de Uidá (1980), do inglês Bruce Chatwin, inspirado na vida do traficante de escravos Francisco Félix de O Souza,1 recebeu, através do cineasta alemão Werner Herzog, uma releitura fílmica igualmente pouco conhecida, com o belo título Cobra Verde (1987). Ambos, escritor britânico e cineasta alemão, parceiros e amigos em franca desarmonia, en- toaram um fabuloso desconcerto a quatro mãos. Entre o documentário e a ficção, entre a grafia e a vida, entre a literatura e o cinema, neste saudável contágio, falaremos sobre o processo de transposição midi- ática, trazendo breve incursão teórica e a prática desenvolvida por estas polêmicas figuras. Para estudar a migração do texto literário para o fílmico, temos o aporte teórico das Intermidialidades (Clüver, 2006). A pesquisa sobre a Intermidialidade tem um inventário crítico fixo na comunidade de pesquisa de falantes de alemão, e amplo desenvolvimento em vários países da Europa e Estados Unidos; na Uni- versidade de Montreal, Canadá, foi criado, no ano de 1997, o Centre de Recherche sur l’Intermedialité (C.R.I.).2 36 ALCEU - v.18 - n.36 - -

Werner Herzog Retrospective

Home Category / Arts and Culture / Werner Herzog Retrospective Werner Herzog Retrospective Slave trade abolition in Cobra Verde Share it! 28 SHARES Published May 15, 2017, 12:05 AM By Rica Arevalo Film director Werner Herzog is a leading gure of the New German Cinema. Born on Sept. 5, 1942, his lms are unconventional and important with the art house audience. The Goethe-Institut Philippinen in partnership with the Film Development Council of the Philippines is showing Herzog’s acclaimed lms until June 4. On May 20, 6 p.m., Cobra Verde (1987) starring Klaus Kinski based on the novel, The Viceroy of Ouidah by Bruce Chatwin, is going to be screened at the FDCP Cinematheque Manila. Kinski plays Francisco Manoel da Silva, nicknamed Cobra Verde, a bandit who walks barefoot and does not own a horse for travelling. People are afraid and run away from him. He tells a bar owner that he never had a friend in all his life. At that time, slave trade was ourishing in Brazil. Black men were sold in exchange for ammunition, liquor, and silk. Cobra Verde meets Don Octavio, a sugar plantation owner who asks him to manage his elds. He accepted the job oer but impregnated Don Octavio’s daughters. To banish him, he was sent to Africa to buy slaves knowing that he will not survive. Cobra Verde took hold of a garrison, Fort Elmina, improved the place and lived there managing the slaves with Taparica (King Ampaw). The slave trade across the Atlantic and Brazil was their route. Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski But “btlack people believe the devil is white” so the King’s men captured the two. -

Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College

Werner Herzog's Debt to Georg Buchner Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College The filmmaker Wemcr Herzog has been labeled eve1)1hing from a romantic, visionary idealist and seeker of transcendence to a reactionary. regressive fatalist and t)Tannical megalomaniac. Regardless of where viewers may place him within these e:-..1reme positions of the spectrum, they will presumably all admit that Herzog personifies the true auteur, a director whose unmistakable style and wor1dvie\v are recognizable in every one of his films, not to mention his being a filmmaker whose art and projected self-image merge to become one and the same. He has often asserted that film is the art of i1literates and should not be a subject of scholarly analysis: "People should look straight at a film. That's the only \vay to see one. Film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates. And film culture is not analvsis, it is agitation of the mind. Movies come from the count!)' fair and circus, not from art and academicism" (Greenberg 174). Herzog wants his ideal viewers to be both mesmerized by his visual images and seduced into seeing reality through his eyes. In spite of his reference to fairgrounds as the source of filmmaking and his repeated claims that his ·work has its source in images, it became immediately transparent already after the release of his first feature film that literature played an important role in the development of his films, a fact which he usually downplays or effaces. Given Herzog's fascination with the extremes and mysteries of the human condition as well as his penchant for depicting outsiders and eccentrics, it comes as no surprise that he found a kindred spirit in Georg Buchner whom he has called "probably the most ingenious writer for the stage that we ever had" (Walsh 11). -

Rescue Dawn La Cavale Secours À L’Aube — États-Unis 2007, 126 Minutes Charles-Stéphane Roy

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 03:04 Séquences La revue de cinéma Rescue Dawn La cavale Secours à l’aube — États-Unis 2007, 126 minutes Charles-Stéphane Roy Léo Bonneville 1919-2007 Numéro 250, septembre–octobre 2007 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/58972ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (imprimé) 1923-5100 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Roy, C.-S. (2007). Compte rendu de [Rescue Dawn : la cavale / Secours à l’aube — États-Unis 2007, 126 minutes]. Séquences, (250), 43–43. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2007 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ CRITIQUES I LES FILMS RESCUE DAWN I La cavale // fut un temps où les bravades de Werner Herzog dans des contrées impossibles attiraient les badauds par milliers dans les salles. Après avoir été jusqu'au bout de l'enfer et en être revenu d'innombrables fois, l'Allemand a délaissé la fiction le temps de plusieurs documentaires réussis, plus inspiré par les vrais fous que par ses créations. -

Bruce Chatwin E Werner Herzog, Livro E Filme: Vidas Entrelaçadas1

Dossiê – N. 32 – 2016.2 – Mariana Castro de Alencar Maria Cristina Cardoso Ribas Bruce Chatwin e Werner Herzog, livro e filme: vidas entrelaçadas1 Mariana Castro de Alencar2 Maria Cristina Cardoso Ribas3 Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Resumo: Este artigo apresenta o encontro entre o cineasta alemão Werner Herzog e o autor inglês Bruce Chatwin, suas afinidades na trajetória de vida, pensamento e obra, analisando suas vivências entrelaçadas e guiadas sempre pelo amor à arte, às viagens e às experiências intensas de vida em relação aos seus modi operandi. Nessa mistura, surgiu, em parceria, não somente um produto singular - o filme Cobra Verde -, mas também um encontro de vida, arte, e incansável busca pelo autoconhecimento que valoriza os limites humanos. Herzog encontrou em Chatwin a personificação da intensidade sinestésica no simples desejo de contar histórias, potência estética das obras de ambos, tecidas por elementos inusitados que vão de paisagens impossíveis a elencos ímpares que atuam e interferem nas sequências. Bruce Chatwin ofereceu ao cineasta um exemplo de aproveitamento da vida de forma descomedida, que dialoga bem com a práxis cinematográfica do colega cineasta. Do valioso encontro de seus projetos artísticos, destacam-se o aspecto sacramental da marcha (Chatwin) e a definição impossível dos limites da visão (Herzog), cujo impacto é partilhado especialmente na adaptação fílmica - Cobra Verde - de o romance O Vice-Rei de Uidá. Palavras-chave: Werner Herzog. Bruce Chatwin. Cobra Verde. O Vice-Rei de Uidá. Literatura e cinema. O encontro de duas personalidades assemelha-se ao contato de duas substâncias químicas: se alguma reação ocorre, ambos sofrem uma transformação. -

Bruce Chatwin, a Kindred Spirit Who Dedicated His Life to Illuminating the Mysteries of the World

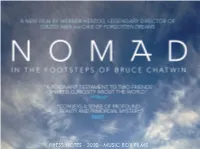

PRESS NOTES - 2020 - MUSIC BOX FILMS LOGLINE Werner Herzog travels the globe to reveal a deeply personal portrait of his friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit who dedicated his life to illuminating the mysteries of the world. SYNOPSIS Werner Herzog turns the camera on himself and his decades-long friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit whose quest for ecstatic truth carried him to all corners of the globe. Herzog’s deeply personal portrait of Chatwin, illustrated with archival discoveries, film clips, and a mound of “brontosaurus skin,” encompasses their shared interest in aboriginal cultures, ancient rituals, and the mysteries stitching together life on earth. WERNER HERZOG Werner Herzog was born in Munich on September 5, 1942. He grew up in a remote mountain village in Bavaria and studied History and German Literature in Munich and Pittsburgh. He made his first film in 1961 at the age of 19. Since then he has produced, written, and directed more than sixty feature- and documentary films, such as Aguirre der Zorn Gottes (AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD, 1972), Nosferatu Phantom der Nacht (NOSFERATU, 1978), FITZCARRALDO (1982), Lektionen in Finsternis (LESSONS OF DARKNESS, 1992), LITTLE DIETER NEEDS TO FLY (1997), Mein liebster Feind (MY BEST FIEND, 1999), INVINCIBLE (2000), GRIZZLY MAN (2005), ENCOUNTERS AT THE END OF THE WORLD (2007), Die Höhle der vergessenen Träume (CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS, 2010). Werner Herzog has published more than a dozen books of prose, and directed as many operas. Werner Herzog lives in Munich and Los Angeles. -

Palace Sculptures of Abomey Combines Color Photographs of the Bas-Reliefs with a Lively History of Dahomey, Complemented by Rare Historical Images

114 SUGGESTED READING Suggested Reading Assogba, Romain-Philippe. Le Musee d'Histoire Moss, Joyce, and George Wilson. Peoples de Ouidah: Decouverte de la COte des Esc/aves. of the Wo rld: Africans South of the Sahara. Ouidah, Benin: Editions Saint Michel, 1994. Detroit and London: Gale Research, 1991. Beckwith, Carol, and Angela Fisher. Pliya, Jean. Dahomey. Issy-les-Moulineaux, "The African Roots of Vo odoo." Na tional France: Classiques Africains, 1975. Geographic Magazine 88 (August 1995): 102-13. Ronen, Dov. Dahomey: Between Tradition and Blier, Suzanne Preston. African Vo dun: Art, Modernity. Ithaca, N.Y., and London: Cornell Psychology, and Power. Chicago: University of University Press, 1975. Chicago Press, 1995. Waterlot, E. G. Les bas-reliefs des Palais Royaux ___. "The Musee Historique in Abomey: d'Abomey. Paris: Institut d'Ethnologie, 1926. Art, Politics, and the Creation of an African Museum." In Arte in Africa 2. Florence: Centro In addition to the scholarly works listed above, di Studi di Storia delle Arte Africane, 1991. interested readers may consult Archibald ___. "King Glele of Danhome: Divination Dalzel's account of Dahomey in the late eigh Portraits of a Lion King and Man of Iron." teenth century, The History of Dahomy: African Arts 23, no. 4 (October 1990): 42-53, An Inland Kingdom ofAf rica (1793; reprint, London, Frank Cass and Co., 1967), and Sir 93-94· Richard Burton's A Mission to Gelele, King of "The Place Where Vo dun Was Born." Dahome (1864; reprint, London, Routledge & Na tural History Magazine 104 (October 1995): Kegan Paul, 1966); both offer historical 40-49· European perspectives on the Dahomey king Decalo, Samuel. -

A Collection of Essays on Werner Herzog

Encounters at the End of the World: A Collection of Essays on Werner Herzog Author: Michael Mulhall Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/542 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Encounters at the End of the World: A Collection of Essays on Werner Herzog “I am my films” Michael Mulhall May 1, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 5. Chapter 1: Herzog’s Cultural Framework: Real and Perceived 21. Chapter 2: Herzog the Auteur 35. Chapter 3: Herzog/Kinski 48. Chapter 4: Blurring the Line 59. Works Cited Werner Herzog is one of the most well-known European art-house directors alive today (Cronin viii). Born in 1944 in war-torn Munich, Herzog has been an outsider from the start. He shot his first film, an experimental short, with a stolen camera. He has infuriated and confounded countless actors, producers, crew-members and studios in his lengthy career with his insistence on doing things his own way. Due to this maverick persona and the specific “adventurous madman” mystique he has cultivated over the past forty years, Herzog has attracted a large following worldwide. Herzog is perhaps best known for the lush but unforgiving jungles of Aguirre: Der Zorn Gottes (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) and his contemplative musings on the structures of society in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) and Stroszek (1977). Though he has never been a huge commercial success in terms of theater receipts, he has had a relatively impressive recent run at the box office, including the much-heralded Grizzly Man (2005) and his long awaited return to feature filmmaking, Rescue Dawn (2006). -

Complete Works Films

Complete works Films 2020 Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds 2019 Family Romance, LLC 2019 NOMAD – In the footsteps of Bruce Chatwin 2018 Meeting Gorbachev (co-director André Singer) 2017 Into the Inferno 2016 Salt and Fire 2016 Lo and Behold 2014 Queen of the Desert 2013 From One Second to the Next 2012/13 On Death Row I + II WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 2011 Into the Abyss - A Tale of Death, a Tale of Life 2010 Ode auf den Morgen der Menschheit (Ode to the Dawn of Man) 2010 Die Höhle der vergessenen Träume (Cave of Forgotten Dreams) 2009 La Bohéme 2009 My Son My Son What Have Ye Done 2008 Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans 2007 Encounters at the End of The World 2006 Rescue Dawn 2005 The Wild Blue Yonder 2005 Grizzly Man 2004 The White Diamond 2003 Rad der Zeit (Wheel of Time) WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 2002 Christ and Demons in New Spain 2001 Ten Thousand Years Older 2001 Pilgrimage 2000 Invincible 1999 Gott und die Beladenen (The Lord and the Laden) 1999 Mein liebster Feind (My Best Fiend) 1999 Schwingen der Hoffnung aka Julianes Sturz in den Dschungel (Wings of Hope) 1997 Little Dieter Needs to Fly 1995 Tod für fünf Stimmen (Death for Five Voices) 1994 Die Verwandlung der Welt in Musik (The Transformation of the World into Music) 1993 Glocken aus der Tiefe (Bells from the Deep) 1992 Lektionen in Finsternis (Lessons of Darkness) 1991 Film Lektionen (Film Lesson) WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria -

Motifs of Fiction in Werner Herzog's Films Chantal Poch [email protected], Pompeu Fabra University

Inner and deeper: Motifs of fiction in Werner Herzog's films Chantal Poch [email protected], Pompeu Fabra University Volume 7.2 (2019) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI /cinej.2019.224 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The emphasis on the mix of facts and inventions has prevailed in the studies about Bavarian director Werner Herzog’s treatment of fiction, leading to the same result again and again: for Herzog, poetic truth is more important than factual truth. But how can we go beyond this conclusion? This paper will try to open an alternative path of analysis more adequate to his philosophy of filmmaking, one that works through the detection of visual and narrative motifs in his films, thus searching the impact of Herzog’s idea of fiction into his poetics. Keywords: Werner Herzog; German Cinema; Motifs; Fiction; Ecstatic Truth New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Inner and deeper: Motifs of fiction in Werner Herzog's films Chantal Poch Introduction Asking ourselves about the nature of fiction in film brings up to the question whether this fiction acts as an opposite of truth or, indeed, as truth itself. Bavarian director Werner Herzog has built an entire oeuvre regarding this problem: from the blurry lines between his fictional movies and documentaries to the recurrent inclusion of false quotes and events on his scripts, all of his films seem to add something to the same direction: the confusion of fact and fiction. -

The Return of the Corpses. Nosferatu, Phantom Der Nacht (Werner Herzog)

The Corona Crisis in Light of the Law-as-Culture Paradigm http://www.recht-als-kultur.de/de/aktuelles/ The Return of the Corpses. Nosferatu, Phantom der Nacht (Werner Herzog) Alexandre Vanautgaerden It's hard to be sententious or a preacher while people are dying. Dead people, who we don't see. In Wuhan, the epicenter of the pandemic, the real surprise was the thousands of funeral urns that appeared after the deconfinement. The corpses, reduced to ashes, came to unmask the lie of Chinese power about the real number of deaths1. On Good Friday, we heard a singular St. John Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the empty St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, a tenor sang alone, accompanied by a harpsichordist and a xylophonist2. Turning away from the nave, without any congregation or music lovers, Benedikt Kristjánsson sings the first chorus (Herr, unser Herrscher) in front of the church choir. He is filmed from behind, his long hair falling over his shoulders. The slow gestures of the singer, his movements that seem choreographed, resonate with the portrait of Christ transmitted by Renaissance and Baroque painting. For more than a month now, thousands of texts have been written about coronavirus all over the world. Our society largely rejects the idea of God. The virus crept into the center a deserted sanctuary. Thousands of texts are now converging on it. Biologists, virologists, sociologists, politicians, journalists, all write and express themselves, with as much passion as the theologians of the past. Faced with the arbitrariness of death, everyone tries to make up for the absence of meaning by looking for a historical or literary referent. -

Friday Film Fest Series Cobra Verde

The Director: THE GERMAN SOCIETY’S Werner Herzog (Werner Stipetic) was born Sept. 5, 1942 in Munich. He grew up on a farm in the Bavarian mountains. After his parents' divorce, he moved to Munich with his mother, and Friday Film Fest Series attended high school there, graduating in 1961. Herzog later studied history, literature and drama in Munich and then in Pittsburgh on a Fulbright scholarship. He eventually broke off his studies and began to teach himself filmmaking. He never attended a film school and has no formal film education. In 1964 he won the Carl Mayer Prize for the screenplay that was to become his first feature film, Signs of Life (1967)/ Lebenszeichen , which was financed by the Kuratorium Junger Deutscher Film and won the Bundesfilmpreis for best first feature. By both circumstance and temperament, Herzog belongs to the New German Cinema (dominant in the Federal Republic of Germany 1965-1982), along with such figures as Rainer Fassbinder and Wim Wenders. The classical German film tradition represented by F. W. Murnau, Fritz Lang and others having been shattered by the Nazi era, Herzog and his contemporaries were starting from a “common ground zero” of new filmmaking. “We had no fathers, only grandfathers” says Herzog in reference to this lost heritage. Herzog, the so-called "visionary" of the New German Cinema, has said that "film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates." Accordingly, in his films the visual is said to predominate over the verbal, where the audience is able to “see” the film emotionally or spiritually rather than “read” it analytically.