CONCLUSIONS Monenergism-Monothelitism And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Complete Course

A Complete Course Forum Theological Midwest Author: Rev.© Peter V. Armenio Publisher:www.theologicalforum.org Rev. James Socias Copyright MIDWEST THEOLOGICAL FORUM Downers Grove, Illinois iii CONTENTS xiv Abbreviations Used for 43 Sidebar: The Sanhedrin the Books of the Bible 44 St. Paul xiv Abbreviations Used for 44 The Conversion of St. Paul Documents of the Magisterium 46 An Interlude—the Conversion of Cornelius and the Commencement of the Mission xv Foreword by Francis Cardinal George, to the Gentiles Archbishop of Chicago 47 St. Paul, “Apostle of the Gentiles” xvi Introduction 48 Sidebar and Maps: The Travels of St. Paul 50 The Council of Jerusalem (A.D. 49– 50) 1 Background to Church History: 51 Missionary Activities of the Apostles The Roman World 54 Sidebar: Magicians and Imposter Apostles 3 Part I: The Hellenistic Worldview 54 Conclusion 4 Map: Alexander’s Empire 55 Study Guide 5 Part II: The Romans 6 Map: The Roman Empire 59 Chapter 2: The Early Christians 8 Roman Expansion and the Rise of the Empire 62 Part I: Beliefs and Practices: The Spiritual 9 Sidebar: Spartacus, Leader of a Slave Revolt Life of the Early Christians 10 The Roman Empire: The Reign of Augustus 63 Baptism 11 Sidebar: All Roads Lead to Rome 65 Agape and the Eucharist 12 Cultural Impact of the Romans 66 Churches 13 Religion in the Roman Republic and 67 Sidebar: The Catacombs Roman Empire 68 Maps: The Early Growth of Christianity 14 Foreign Cults 70 Holy Days 15 Stoicism 70 Sidebar: Christian Symbols 15 Economic and Social Stratification of 71 The Papacy Roman -

Monenergism Monothelitism Versus Dyenergism

CHAPTER THREE ‘IMPERIAL’ MONENERGISMMONOTHELITISM VERSUS DYENERGISMDYOTHELITISM In this section, I shall explore simultaneously (to the degree that existing sources allow) the ‘imperial’ or ‘Chalcedonian’ Monenergism- Monothelitism and Dyenergism-Dyothelitism, with the objective of clarifying the similarities and diff erences between the two oposing doctrines. 3.1. Key notions 3.1.1. Th e oneness of Christ Owing to a common neo-Chalcedonian background, adherents of both Monenergite-Monothelite and Dyenergite-Dyothelite doctrines accepted the oneness of Christ as a fundamental starting point. Monenergists- Monothelites, however, placed more emphasis on this oneness. In the relatively brief Alexandrian pact, for example, the oneness of Christ is referred to more than twenty times. All statements about the single energeia and will were normally preceded by a confession of Christ’s oneness.1 Dyenergists-Dyothelites also began their commentaries on energeia and will by postulating the oneness, though not as frequently or as insistently as their opponents. In one of the earliest Dyenergist- Dyothelite texts, the encyclical of Sophronius, a statement of faith on the two energeiai and wills begins with a reference to Christ’s oneness .2 In these and many other ways, both parties demonstrated their adherence to the Christological language of Cyril of Alexandria. 1 2 5–6 See the Pact of the Alexandrian union (ACO2 II 598 ), Sergius ’ letter to Pope 2 6–7 29–31 Honorius (ACO2 II 542 ), Ecthesis (ACO2 I 158 ). 2 1 17–18 ACO2 II 440 . 104 chapter three 3.1.2. One hypostasis and two natures Th e followers of the Monenergist-Monothelite doctrine as it emerged in the seventh century, were Chalcedonians who felt it necessary to make a clear distinction between Christ’s hypostasis and his nature. -

The Development of Marian Doctrine As

INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, OHIO in affiliation with the PONTIFICAL THEOLOGICAL FACULTY MARIANUM ROME, ITALY By: Elizabeth Marie Farley The Development of Marian Doctrine as Reflected in the Commentaries on the Wedding at Cana (John 2:1-5) by the Latin Fathers and Pastoral Theologians of the Church From the Fourth to the Seventeenth Century A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology with specialization in Marian Studies Director: Rev. Bertrand Buby, S.M. Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, OH 45469-1390 2013 i Copyright © 2013 by Elizabeth M. Farley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Nihil obstat: François Rossier, S.M., STD Vidimus et approbamus: Bertrand A. Buby S.M., STD – Director François Rossier, S.M., STD – Examinator Johann G. Roten S.M., PhD, STD – Examinator Thomas A. Thompson S.M., PhD – Examinator Elio M. Peretto, O.S.M. – Revisor Aristide M. Serra, O.S.M. – Revisor Daytonesis (USA), ex aedibus International Marian Research Institute, et Romae, ex aedibus Pontificiae Facultatis Theologicae Marianum, die 22 Augusti 2013. ii Dedication This Dissertation is Dedicated to: Father Bertrand Buby, S.M., The Faculty and Staff at The International Marian Research Institute, Father Jerome Young, O.S.B., Father Rory Pitstick, Joseph Sprug, Jerome Farley, my beloved husband, and All my family and friends iii Table of Contents Prėcis.................................................................................. xvii Guidelines........................................................................... xxiii Abbreviations...................................................................... xxv Chapter One: Purpose, Scope, Structure and Method 1.1 Introduction...................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose............................................................ -

The Concept of “Sister Churches” in Catholic-Orthodox Relations Since

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Will T. Cohen Washington, D.C. 2010 The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II Will T. Cohen, Ph.D. Director: Paul McPartlan, D.Phil. Closely associated with Catholic-Orthodox rapprochement in the latter half of the 20 th century was the emergence of the expression “sister churches” used in various ways across the confessional division. Patriarch Athenagoras first employed it in this context in a letter in 1962 to Cardinal Bea of the Vatican Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, and soon it had become standard currency in the bilateral dialogue. Yet today the expression is rarely invoked by Catholic or Orthodox officials in their ecclesial communications. As the Polish Catholic theologian Waclaw Hryniewicz was led to say in 2002, “This term…has now fallen into disgrace.” This dissertation traces the rise and fall of the expression “sister churches” in modern Catholic-Orthodox relations and argues for its rehabilitation as a means by which both Catholic West and Orthodox East may avoid certain ecclesiological imbalances toward which each respectively tends in its separation from the other. Catholics who oppose saying that the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church are sisters, or that the church of Rome is one among several patriarchal sister churches, generally fear that if either of those things were true, the unicity of the Church would be compromised and the Roman primacy rendered ineffective. -

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Heresy Description Origin Official

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Official Heresy Description Origin Other Condemnation Adoptionism Belief that Jesus Propounded Theodotus was Alternative was born as a by Theodotus of excommunicated names: Psilanthro mere (non-divine) Byzantium , a by Pope Victor and pism and Dynamic man, was leather merchant, Paul was Monarchianism. [9] supremely in Rome c.190, condemned by the Later criticized as virtuous and that later revived Synod of Antioch presupposing he was adopted by Paul of in 268 Nestorianism (see later as "Son of Samosata below) God" by the descent of the Spirit on him. Apollinarism Belief proposed Declared to be . that Jesus had by Apollinaris of a heresy in 381 by a human body Laodicea (died the First Council of and lower soul 390) Constantinople (the seat of the emotions) but a divine mind. Apollinaris further taught that the souls of men were propagated by other souls, as well as their bodies. Arianism Denial of the true The doctrine is Arius was first All forms denied divinity of Jesus associated pronounced that Jesus Christ Christ taking with Arius (ca. AD a heretic at is "consubstantial various specific 250––336) who the First Council of with the Father" forms, but all lived and taught Nicea , he was but proposed agreed that Jesus in Alexandria, later exonerated either "similar in Christ was Egypt . as a result of substance", or created by the imperial pressure "similar", or Father, that he and finally "dissimilar" as the had a beginning declared a heretic correct alternative. in time, and that after his death. the title "Son of The heresy was God" was a finally resolved in courtesy one. -

Index to Volume I

INDEX TO VOLUME I to position of authority, 558 Aseitas Dei. See Essence of God. A Athanasian Creed, 201 Abortion, 275 Atheism, 61 Active obedience, 592, 593 errors Adiaphora God's cooperation, 240 and Christian freedom, 616 problem of evil, 103 definition, 31 Atonement, 605 family planning/birth control, 272 Attributes of God, 63–144 Adoptionism, 198, 514 different classifications, 67 Aeternitas. See Attributes of God: eternity. immanent, 69–81 Alloeosis, 517 eternity, 74–76 Angel of the Lord, 169, 324 immutability, 69–74 Angels, 319–41 love, 76–78 abilities, 335 perfection/goodness, 78–81 Angel of the Lord, 169, 324 bliss, 79 confirmed in holiness, 330 majesty, 79, 491 creation of, 326 immanent/transitive classification, 69 evil. See Demons. manifestations of love, 63 fall of, 342 not distinct from essence, 64 Gabriel, 323 transitive, 81–144 Greek/Hebrew words for, 324 holiness, 119–27 guardian, 339 Michael, 323 demanded of men, 119 number, 329 distinguished from justice, 124 personal, spiritual beings, 322 related to truthfulness, 124 ranks, 331 serve God in various ways, 337 justice/righteousness, 127–44 serve God's people, 338 Christ’s imputed righteousness, 137 testify to Son's deity, 175 not annulled by apparent injustice, 131 visible forms, 333 worship of, 341 proclaimed as gospel, 137 Animism, 61 proclaimed as law, 127 Annulment, 279 punishment, 133 Anthropomorphism love, 108–19 applied analogically, 62 causae of God's will, 146 classifications, 109 definition, 61 Greek/Hebrew terms, 112 of God's foreknowledge, 98 omnipotence, 139–44 of God's omniscience, 94 ordinata/absoluta, 143 Anthropopathism omnipresence, 81–86 applied analogically, 62 definition, 61 active presence, 81 of God's repentance, 71 errors, 84 Apollinarius, 504 related attributes, 81 Archangels. -

Theological Equipping Class Christological Heresies February 21, 2021

Theological Equipping Class Christological Heresies February 21, 2021 Recap: What are Heresies? "a doctrine that ultimately destroys, destabilizes, or distorts a mystery rather than preserving it" (Alistair McGrath) Trinity: unity, plurality, equality, mystery - how do Trinitarian heresies "minimize the mystery"? Christology: humanity, deity – how do Christological heresies tend to "minimize the mystery"? Major Heresies of the First Two Centuries of the Church: legalism and dualism Major Heresies of the Next Two Centuries: Trinitarian heresies (Arianism, adoptionism, & modalism) Five Christological Heresies to consider today: 1. Apollinarianism 2. Nestorianism 3. Eutychianism 4. Monophysitism 5. Monothelitism Context and Significance Political jockeying for preeminence Emphases of Alexandria and Antioch Why does this really matter? ● Does God actually save man? Well, in order to do so, God must become man. So if Jesus isn't God or isn't man, that doesn't happen! ● When it comes to Trinitarian heresies, we established that it is truly God who comes down. But today we will address the question of whether He comes down far enough. Does the Son of God actually incarnate, unite Himself to humanity; or does He just come part of the way? Is He only partly human and thus we are only partly saved. 1 Apollinarianism ● Apollinaris (sometimes Apollinarius) of Laodicea (360s & 370s) ● What is humanity? Spirit + flesh/body o the immaterial logos was simply clothed with physicality ● So Christ possessed a human body, but not a human soul or mind or emotions, or, as it would be called in Greek, a "rational soul." ● Is Jesus fully human? o God in a man suit ● What drives Apollinaris? o Fear that if Christ is truly and fully human with a human mind and soul, then that will somehow compromise or taint Christ. -

Why the Russian Baptists Are Neither Arminians Nor Calvinists

Why the Russian Baptists Are Neither Arminians nor Calvinists «Theological Reflections» 2013. Vol. #14. Pp. 199#212 Constantine PROKHOROV, Omsk, Russia © К. Prokhorov, 2013 he theological tradition of synergy (cooperation) between Tdivine grace and free will was never interrupted in the Christian East; it remained almost untouched by the theolog ical controversies of the West.[1] According to the Russian phi losopher L. A. Zander, Eastern Christian theology differs greatly from Western classical doctrines because it did not ex perience any comparable influence from Augustine’s anthro pology, Anselm’s teaching on redemption, and the Scholas tic methodology of Thomas Aquinas.[2] Something similar may be said about the teachings of the Dutch theologian Jacob Arminius in Russia and the Soviet Union, so that sooner or later we must declare the absence of any significant relationship between the views of the latter and Constantine Prokhorov of the RussianUkrainian Evangelical movement (including is a graduate of North Ka [3] zakhstan University and the Russian Baptists, in particular). Arminius, who lived in Odessa Theological Semi the second half of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centu nary (Ukraine) and holds ries in Amsterdam and Leiden, was, strictly speaking, a Re his MTh and PhD degrees formed pastor. That is, he based his views upon completely from IBTS, Prague, Czech Republic / University of different doctrinal grounds; his thinking belonged to another Wales. He has published system of theological coordinates in comparison with Eastern, articles in the periodicals Slavic Christianity from which the Russian evangelical move Grani, Continent, Bogo ment mainly originated. What Arminius did in his life, above myslie, and others. -

Confirmation Workbook 2016-2017

The Holy Sacrament of Confirmation Workbook 2016-2017 Icon of Pentecost © by Monastery Icons – www.monasteryicons.com Used with permission. “Come Holy Spirit and inflame our hearts with the fire of divine love!” Darryl Adams 540-622-8073, [email protected] St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church, Front Royal, VA A.M.D.G Table of Contents Weekly Class Schedule 5 Confirmation Preparation Entrance Questionnaire 6 Note to Parents 7 Specific Confirmation Prayers 8 Summary of the Faith of the Church 9 Summary of Basic Prayers 10 Preparation Checklist 12 Forms and Requirements (Final Requirements start on page 121) Confirmation Sponsor Certificate*1 14 Choosing a Patron Saint and Sponsor 16 Sponsor & Proxy Form* 19 Retreat from* 21 Patron Saint Report 23 Historical Report 24 Gospel Report 26 Apostolic Project 28 Apostolic Project Proposal Form 31 Apostolic Project Summary Form (2 pages) 33 THE EXISTENCE OF GOD 36 The Problem of Evil 39 Hell is Real 43 Guardian Angels including information from St. Padre Pio 47 Guardian Angel Litany 51 The Last Things 52 SACRED SCRIPTURE 55 Are the Books of the New Testament Reliable Historical Documents? 56 How do the Books of the New Testament indicate the manner in which they are supposed to be read? 57 Where the rubber hits the road… 59 How does the Church further instruct us on how to read the Holy Bible? 60 The Bottom Line 61 Diagram of Highlights of Christ’s Life 62 THE DIVINITY OF CHRIST AND THE HOLY TRINITY 63 What Jesus did and said can be done by no man 64 Who do people say that He is? 66 -

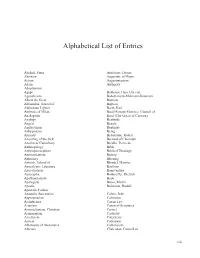

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

The Relevance of Maximus the Confessor's Theology of Creation For

MAXIMUS AND ECOLOGY: THE RELEVANCE OF MAXIMUS THE CONFESSOR’S THEOLOGY OF CREATION FOR THE PRESENT ECOLOGICAL CRISIS by RADU BORDEIANU ELIGIOUS communities all over the world are presenting the R relevance of their traditions to the contemporary ecological crisis in one of the most commendable accomplishments of inter- religious dialogue: common concern for the environment.1 Surprisingly, some contemporary theologians consider that the Christian patristic tradition does not have the proper resources to offer a solution in this context and might even be a significant cause of today’s situation. They criticize Christianity for allegedly separating human beings from the rest of creation, being anthropocentric, and allowing the abuse of creation. They propose a wide range of solutions, including turning towards animist religions or adopting an attitude towards creation that tends toward pantheism, which would in turn bring humanity closer to creation.2 In response, I suggest that it is both possible and imperative for Christianity to actualize its traditional theology of creation and make it instrumental in opposing today’s ecocide. Christian Tradition, as represented in the works of Maximus the Confessor, condemns the attitudes that perpetuate the present environmental crisis, and offers spiritual solutions to solve it, based on the understanding of the human person as the centre of creation. Despite its immediate etymological implication, this position cannot be labelled as anthropocentric, since the human being is ascribed a priestly role, of gathering the logoi of creation and offering them eucharistically to the Logos. Ultimately, Maximus’s theology of creation and anthropology are theocentric. 103 104 THE DOWNSIDE REVIEW After some biographical and bibliographical information about Maximus, I present his theology of creation and its relevance to the present ecological crisis. -

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies Edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press. Cover design by David Manahan, o.s.b. Cover symbol by Frank Kacmarcik, obl.s.b. © 2007 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies / edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff. p. cm. “A Michael Glazier book.” ISBN-13: 978-0-8146-5856-7 (alk. paper) 1. Religion—Dictionaries. 2. Religions—Dictionaries. I. Espín, Orlando O. II. Nickoloff, James B. BL31.I68 2007 200.3—dc22 2007030890 We dedicate this dictionary to Ricardo and Robert, for their constant support over many years. Contents List of Entries ix Introduction and Acknowledgments xxxi Entries 1 Contributors 1519 vii List of Entries AARON “AD LIMINA” VISITS ALBIGENSIANS ABBA ADONAI ALBRIGHT, WILLIAM FOXWELL ABBASIDS ADOPTIONISM