Examinations of Projected Freedom: Photography and the Spaces of the American West” by Andrew Gansky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Alain Sayag.Pdf

tWesley Essalts: Staceyt 7he Road and the American tradition; Remembering Rennie Ellis, John Szarkowski and Michael Riley; Daniel Mudie Cunningham revisits \Tilliam Yangt queer nine- ries; A speculative exhibition: Aspects of recenr photog raphy. Iuteruiews: Graham Howe, Tamara \7inikoff and Alain Sayag. Porrfolias.' Narelle Autio and Tlent Parke , J. D. 'okhai ojeikere, Tacita Dean, Greg Semu and Angelica Mesiti Vo/. 93 Spring/Summer 2013 14 AU$19.95, NZg23 Photofile ,Ilil|ilililIililffiililIi THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS: FROM THE 19705 TO NoW A photog,aph is not just An irnage, tt ts also an object' Alain Sayag was a curator at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris from the early 1970s - that is to say before the Centre Pompidou building opened to house itin 1977 - until 2007.In 1981 he became the head of the newly established Photography Depart- ment there and started to develop the museum collection with this specificity in mind. He has published widely on the subject, for the Centre Pompidou and in other contexrs. Throughout his career he also worked closely with Agntss de Gouvion Saint Cyr on the photographic acquisition panel of the FNAC (the French National Contemporary Art Fund). He met and exhibited the Australian photographer Robert Besanko in Paris in 1980-81, but only travelled to Australia a few times in the late 1990s.1 \(/hile also fo- cusing on his other passion for horseriding, today Sayag curates exhibitions worldwide and his expertise is highly sought after to advise collections or photography festivals. Alain Sayag's analytical 4 d o act of looking o L O c tr o Interview by Caroline Hancock € ! o L j =F o) c o ! 5 ? G a E i Opposite page: Alain Sayag in Luzarches, 2005, courtesy Alain Sayag. -

1. Carbon Copy: 6/25 – 6/29 1973

The online Adobe Acrobat version of this file does not show sample pages from Coleman’s primary publishing relationships. The complete print version of A. D. Coleman: A Bibliography of His Writings on Photography, Art, and Related Subjects from 1968 to 1995 can be ordered from: Marketing, Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0103, or phone 520-621-7968. Books presented in chronological order 1. Carbon Copy: 6/25 – 6/29 1973. New York: ADCO interviews” with those five notable figures, serves also as Enterprises, 1973. [Paperback: edition of 50, out of print, “a modest model of critical inquiry.”This booklet, printed unpaginated, 50 pages. 17 monochrome (brown). Coleman’s on the occasion of that opening lecture, was made available first artist’s book. A body-scan suite of Haloid Xerox self- by the PRC to the audiences for the subsequent lectures in portrait images, interspersed with journal/collage pages. the series.] Produced at Visual Studies Workshop Press under an 5. Light Readings: A Photography Critic’s Writings, artist’s residency/bookworks grant from the New York l968–1978. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. State Council on the Arts.] [Hardback and paperback: Galaxy Books paperback, 2. Confirmation. Staten Island: ADCO Enterprises, 1975. 1982; second edition (Albuquerque: University of New [Paperback: first edition of 300, out of print; second edition Mexico Press, 1998); xviii + 284 pages; index. 34 b&w. of 1000, 1982; unpaginated, 48 pages. 12 b&w. Coleman’s The first book-length collection of Coleman’s essays, this second artist’s book. -

Emmet Gowin's Photographs of Edith

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The Photographer's Wife: Emmet Gowin's Photographs of Edith Mikell Waters Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4501 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of the Arts Virginia Commonwealth University This is to certify that the dissertation prepared by Mikell Waters Brown entitled "The Photographer's Wife: Emmet Gowin's Photographs of Edith" has been approved by her committee as satisfactory completion of the dissertation requirement fo r the degree of D Philosophy. , irector, Department of Art History, School of the Arts Dr. Eric Garberson, Reader, Department of Art History, School of the Arts redrika Jacobs, �r,Depalfiii'ent of Art History, School of the Arts Dr. Michael Schreffler, Reader, Department of Art History, School of the Arts Ot1irS'fiIfe"'Reader, Chief Curator, Hirshhorn Museum, Smithsonian Dr. Eric Garberson, Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Art History, School of the Arts Dr. Richard E. Toscan, Dean, School of the Arts Dr. F. Douglas Boudinot, Dean, School of Graduate Studies ©Mikell Waters Brown 2005 All Rights Reserved The Photographer's Wife: Emmet Gowin's Photographs of Edith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University by Mikell Waters Brown, B.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 1981 M.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 1991 Director: Robert C. -

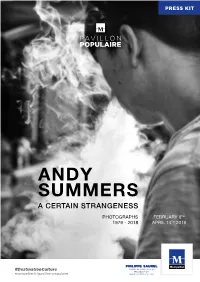

Andy Summers

PRESS KIT “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 ANDY SUMMERS A CERTAIN STRANGENESS PHOTOGRAPHS FEBRUARY 6TH 1979 - 2018 APRIL 14TH 2019 #DestinationCulture montpellier.fr/pavillon-populaire “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” at the Pavillon Populaire in Montpellier from February 6th to April 14th 2019 . 4 Text of intent – Gilles Mora, artistic director of the Pavillon Populaire . 7 Text of intent – Andy Summers . 9 Artist’s biography . 10 2019 Pavillon Populaire programme . 11 Pavillon Populaire: photography made accessible for all. 12 Montpellier, a cultural destination . 13 Montpellier, a candidate for the European Capital of Culture . 17 Press images . 18 2 “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 A WORD FROM PHILIPPE SAUREL The Pavillon Populaire 2018 season – dedicated to the link between history and photography – has been truly outstanding with more than 130 000 visitors for three exhibitions. In 2019, the Pavillon Populaire puts on a new event with the world of Andy Summers, photographer and guitarist of the mythic 80’s rock band The Police. Through his exhibition “A certain strangeness, photographs 1977-2018”, the artist presents us a dense masterpiece, quite similar to a private diary in form of pictures. With more than 250 images, most of which are yet unseen, the exhibition includes the series “Let’s get weird!”, a lucid and corrosive outlook on the ascent of the famous 80’s band. -

AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY from Berenice Abbott to Alec Soth from Berenice Abbott Alec to Soth

T +49 (0)30 54 |F+49 61 (0)30 |[email protected] -211 97 11 -218 |www.kunsthandel-maass.de Kunsthandel Jörg Maaß |Rankestraße Berlin |10789 24 Kunsthandel Jörg Maaß AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY From Berenice Abbott to Alec Soth · 2011 AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY From Berenice Abbott to Alec Soth Abbott to Berenice From 2 AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY From Berenice Abbott to Alec Soth 2 FROM BERENICE ABBOTT TO ALEC SOTH 24 selected photographs The myth of America has begun to falter; however, it still con - It would be impossible to describe all of the important merits tinues to fascinate us to no end. This myth was founded to a and currents of American photography here. Instead the considerable degree by a long list of outstanding photo gra phers. following 24 images by some of the most important American That which is typically American still influences our picture of photographers, should speak for themselves. In the present the United States even today, speaking to us from the images catalogue and exhibition, we would like to introduce one of entire generations. American photography tells us stories of aspect of our gallery’s program: An exciting cross-section of the limited and unlimited possibilities of the country, thereby almost one century of American photo history. Each individual allowing us to participate in the “American Dream”. It tells of the photographer from our selection not only reflects our own rich and the poor, or in other words the everyday lives of the interests, he or she also embodies crucial stages in the develop- people. ment of a specificlanguage of images that is idiosyncratic to photography. -

Two Bodies of American Photographic Work from the 1960S and 1970S

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 15 | 2017 Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies Two Bodies of American Photographic Work from the 1960s and 1970s Joel Meyerowitz: Early Works, Rencontres d’Arles, 3 July-27 August, 2017 / Annie Leibovitz: The Early Years, 1970-1983, Rencontres d’Arles, 27 May–24 September 2017 Daniel Huber Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10932 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.10932 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Daniel Huber, “Two Bodies of American Photographic Work from the 1960s and 1970s”, Miranda [Online], 15 | 2017, Online since 04 October 2017, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/10932 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.10932 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Two Bodies of American Photographic Work from the 1960s and 1970s 1 Two Bodies of American Photographic Work from the 1960s and 1970s Joel Meyerowitz: Early Works, Rencontres d’Arles, 3 July-27 August, 2017 / Annie Leibovitz: The Early Years, 1970-1983, Rencontres d’Arles, 27 May–24 September 2017 Daniel Huber 1 The 48th (2017) edition of Les Rencontres de photographie dʼArles1 offered, amongst its varied and rich programme of some 40 exhibitions, retrospectives of two influential American photographers: Joel Meyerowitz: Early Works as the monographic highlight of the main programme of the Rencontres, and Annie Leibovitz: The Early Years, 1970-1983 as an associated programme commissioned and organized by the private LUMA Foundation. -

American Road Photography from 1930 to the Present A

THE PROFANE AND PROFOUND: AMERICAN ROAD PHOTOGRAPHY FROM 1930 TO THE PRESENT A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Han-Chih Wang Diploma Date August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Professor Gerald Silk, Department of Art History Professor Miles Orvell, Department of English Professor Erin Pauwels, Department of Art History Professor Byron Wolfe, Photography Program, Department of Graphic Arts and Design THE PROFANE AND PROFOUND: AMERICAN ROAD PHOTOGRAPHY FROM 1930 TO THE PRESENT ABSTRACT Han-Chih Wang This dissertation historicizes the enduring marriage between photography and the American road trip. In considering and proposing the road as a photographic genre with its tradition and transformation, I investigate the ways in which road photography makes artistic statements about the road as a visual form, while providing a range of commentary about American culture over time, such as frontiersmanship and wanderlust, issues and themes of the automobile, highway, and roadside culture, concepts of human intervention in the environment, and reflections of the ordinary and sublime, among others. Based on chronological order, this dissertation focuses on the photographic books or series that depict and engage the American road. The first two chapters focus on road photographs in the 1930s and 1950s, Walker Evans’s American Photographs, 1938; Dorothea Lange’s An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, 1939; and Robert Frank’s The Americans, 1958/1959. Evans dedicated himself to depicting automobile landscapes and the roadside. Lange concentrated on documenting migrants on the highway traveling westward to California. -

Protest, Neighborhood, and Street Photography in the (Workers Film And) Photo League

arts Article ‘We Cover New York’: Protest, Neighborhood, and Street Photography in the (Workers Film and) Photo League Barnaby Haran Department of English, Creative Writing, and American Studies, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, UK; [email protected] Received: 1 February 2019; Accepted: 2 May 2019; Published: 10 May 2019 Abstract: This article considers photographs of New York by two American radical groups, the revolutionary Workers Film and Photo League (WFPL) (1931–1936) and the ensuing Photo League (PL) (1936–1951), a less explicitly political concern, in relation to the adjacent historiographical contexts of street photography and documentary. I contest a historiographical tendency to invoke street photography as a recuperative model from the political basis of the groups, because such accounts tend to reduce WFPL’s work to ideologically motivated propaganda and obscure continuities between the two leagues. Using extensive primary sources, in particular the PL’s magazine Photo Notes,I propose that greater commonalities exist than the literature suggests. I argue that WFPL photographs are a specific form of street photography that engages with urban protest, and accordingly I examine the formal attributes of photographs by its principle photographer Leo Seltzer. Conversely, the PL’s ‘document’ projects, which examined areas such as Chelsea, the Lower East Side, and Harlem in depth, involved collaboration with community organizations that resulted in a form of neighborhood protest. I conclude that a museological framing of ‘street photography’ as the work of an individual artist does not satisfactorily encompass the radicalism of the PL’s complex documents about city neighborhoods. Keywords: street photography; documentary; neighborhood; protest; worker photography; propaganda; museum In the February 1938 issue of the Photo League’s bulletin Photo Notes, a brief notice informed that: The newly formed Documentary Group announces that it has embarked on a large project, a document on Chelsea. -

Bernard Plossu Anthropologue. Essai D'interprétation De La Connaissance

Bernard Plossu anthropologue. Essai d’interprétation de la connaissance photographique Jean Kempf To cite this version: Jean Kempf. Bernard Plossu anthropologue. Essai d’interprétation de la connaissance pho- tographique. Focales, Publications de l’Université de Saint-Étienne, 2019, Photographie & Arts de la scène. halshs-02157024 HAL Id: halshs-02157024 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02157024 Submitted on 14 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Focales 3| 2019 Photographie & Arts de la scène Bernard Plossu anthropologue. Essai d’interprétation de la connaissance photographique Jean Kempf Éditeur Publications de l’Université de Saint-Étienne Édition électronique https://focales.univ-st-etienne.fr/index.php?id=2518 ISSN 2556-5125 Référence électronique Olivier Ihl, « Bernard Plossu anthropologue. Essai d’interprétation de la connaissance photogra- phique », Focales n° 3 : Photographie & Arts de la scène, mis à jour le 12/06/2019, URL : https:// focales.univ-st-etienne.fr/index.php?id=2518 © Focales, Université Jean Monnet – Saint-Étienne La reproduction ou représentation de cet article, notamment par photocopie, n’est autorisée que dans les limites des règles de la propriété intellectuelle et artistique. Toute autre reproduction ou représentation, en tout ou partie, sous quelque forme et de quelque manière que ce soit, est interdite sauf accord préa- lable et écrit de l’éditeur. -

Contemporary Architecture and Design the Library of Oscar Riera Ojeda

Contemporary Architecture and Design The Library of Oscar Riera Ojeda Part One: Architecture and Interior Design Part Two: Photography, Fashion, Graphic Design, Product Design 3351 titles in circa 3595 volumes Contemporary Architecture and Design The Library of Oscar Riera Ojeda Part One: Architecture and Interior Design Part Two: Photography, Fashion, Graphic Design, Product Design 3351 titles in circa 3595 volumes The Oscar Riera Ojeda Library comprised of some 3500 volumes is focused on modern and contemporary architecture and design, with an emphasis on sophisticated recent publications. Mr. Riera Ojeda is himself the principal of Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers, and its imprint oropublishers, which have produced some of the best contemporary architecture and design books of the past decade. In addition to his role as publisher, Mr. Riera Ojeda has also contributed substantively to a number of these as editor and designer. Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers works with an international team of affiliates, publishing monographs on architects, architectural practice and theory, architectural competitions, building types and individual buildings, cities, landscape and the environment, architectural photo- graphy, and design and communications. All of this is reflected in the Riera Ojeda Library, which offers an international conspectus on the most significant activity in these fields today, as well as a grounding in earlier twentieth-century architectural history, from Lutyens and Wright through Mies and Barragan. Its coverage of the major architects