Glenn Roberts Anson Mills Columbia, South Carolina *** Date

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here You Will Enjoy a Lunch Pack Which Includes Water and Soft Drinks

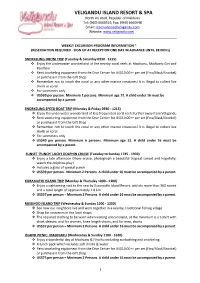

VELIGANDU ISLAND RESORT & SPA North Ari Atoll, Republic of Maldives Tel: (960) 6660519, Fax: (960) 6660648 Email: [email protected] Website: www.veligandu.com WEEKLY EXCURSION PROGRAM INFORMATION * (RESERVATION REQUIRED - SIGN UP AT RECEPTION ONE DAY IN ADVANCE UNTIL 18:00hrs) SNORKELING DHONI TRIP (Tuesday & Saturday 0930 - 1215) v Enjoy the underwater wonderland of the nearby coral reefs at Madivaru, Madivaru Giri and Rasdhoo v Rent snorkeling equipment from the Dive Center for US$10.00++ per set (Fins/Mask/Snorkel) or purchase it from the Gift Shop v Remember not to touch the coral or any other marine creatures! It is illegal to collect live shells or coral v For swimmers only v US$30 Per Person. Minimum 2 Persons. Minimum age 12. A child under 16 must be accomPanied by a Parent. SNORKELING SPEED BOAT TRIP (Monday & Friday 0930 - 1215) v Enjoy the underwater wonderland of less frequented coral reefs further away from Veligandu v Rent snorkeling equipment from the Dive Center for US$10.00++ per set (Fins/Mask/Snorkel) or purchase it from the Gift Shop v Remember not to touch the coral or any other marine creatures! It is illegal to collect live shells or coral v For swimmers only v US$40 Per Person. Minimum 6 Persons. Minimum age 12. A child under 16 must be accomPanied by a Parent. SUNSET ‘PUNCH’ LUCKY DOLPHIN CRUISE (Tuesday to Sunday 1745 - 1930) v Enjoy a late afternoon Dhoni cruise, photograph a beautiful tropical sunset and hopefully, watch the dolphins play! v Includes a glass of special punch v US$39 Per Person - Minimum 2 Persons. -

Concept and Types of Tourism

m Tourism: Concept and Types of Tourism m m 1.1 CONCEPT OF TOURISM Tourism is an ever-expanding service industry with vast growth potential and has therefore become one of the crucial concerns of the not only nations but also of the international community as a whole. Infact, it has come up as a decisive link in gearing up the pace of the socio-economic development world over. It is believed that the word tour in the context of tourism became established in the English language by the eighteen century. On the other hand, according to oxford dictionary, the word tourism first came to light in the English in the nineteen century (1811) from a Greek word 'tomus' meaning a round shaped tool.' Tourism as a phenomenon means the movement of people (both within and across the national borders).Tourism means different things to different people because it is an abstraction of a wide range of consumption activities which demand products and services from a wide range of industries in the economy. In 1905, E. Freuler defined tourism in the modem sense of the world "as a phenomena of modem times based on the increased need for recuperation and change of air, the awakened, and cultivated appreciation of scenic beauty, the pleasure in. and the enjoyment of nature and in particularly brought about by the increasing mingling of various nations and classes of human society, as a result of the development of commerce, industry and trade, and the perfection of the means of transport'.^ Professor Huziker and Krapf of the. -

Cultural Heritage and Tourism: Potential, Impact, Partnership and Governance

CCULTURAL HERITAGE AND TOURISM: POTENTIAL, IMPACT, PARTNERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE The presentations on the III Baltic Sea Region Cultural Heritage Forum 25–27 September in Vilnius, Lithuania Edited by Marianne Lehtimäki Monitoring Group on Cultural Heritage in the Baltic Sea States and Department of Cultural Heritage under Ministry of Culture, Lithuania Published with support of the Department of Cultural Heritage under Ministry of Culture of Lithuania Editor Marianne Lehtimäki Adviser and co-ordinator Alfredas Jomantas © Department of Cultural Heritage under Ministry of Culture, Lithuania 2008 Published by Versus Aureus Design by Saulius Bajorinas Printed by “Aušra” CONTENT INTRODUCTION Cultural heritage and tourism in the Baltic Sea States – Why to read this book 9 Alfredas Jomantas, Lithuania and Marianne Lehtimäki, Finland Cultural heritage in Lithuania: Potential for local and territorial initiatives 13 Irena Vaišvilaitė, Lithuania Cultural tourism – An experience of place and time 16 Helena Edgren, Finland POTENTIAL The experiences of cultural tourism 18 Mike Robinson Cultural heritage as an engine for local development 26 Torunn Herje, Norway Literature tourism linked to intangible cultural heritage 29 Anja Praesto, Sweden Production of local pride and national networks 32 Anton Pärn, Estonia First World War field fortifications as a cultural tourism object 37 Dagnis Dedumietis, Latvia Traditional turf buildings and historic landscapes: the core of cultural tourism in rural Iceland 39 Magnus Skulason, Iceland Archaeology visualised – The Viking houses and a reconstructed jetty in Hedeby 42 Sven Kalmring, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany Underwater attractions – The Kronprins Gustav Adolf Underwater Park 44 Sallamari Tikkanen, Finland Potentials of marine wreck tourism 47 Iwona Pomian, Poland Protection, management and use of underwater heritage in the Baltic Sea region 49 Björn Varenius, Sweden IMPACT How do tourists consume heritage places? 52 Gregory Ashworth The economics of built heritage 59 Terje M. -

Carlow College

- . - · 1 ~. .. { ~l natp C u l,•< J 1 Journal of the Old Carlow Society 1992/1993 lrisleabhar Chumann Seanda Chatharlocha £1 ' ! SERVING THE CHURCH FOR 200 YEARS ! £'~,~~~~::~ai:~:,~ ---~~'-~:~~~ic~~~"'- -· =-~ : -_- _ ~--~~~- _-=:-- ·.. ~. SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL- 9-13 DUBLIN STREET ~ P,•«•11.il H,,rd ,,,- Qua/in- O'NEILL & CO. ACCOUNTANTS _;, R-.. -~ ~ 'I?!~ I.-: _,;,r.',". ~ h,i14 t. t'r" rhr,•c Con(crcncc Roonts. TRAYNOR HOUSE, COLLEGE STREET, CARLOW U • • i.h,r,;:, F:..n~ r;,,n_,. f)lfmt·r DL1nccs. PT'i,·atc Parties. Phone:0503/41260 F."-.l S,:r.cJ .-\II Da,. Phone 0503/31621. t:D. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD. Jewellers, ·n~I, Fashion Boutique, Fuel Merchant. Authorised Ergas Stockist ·~ff 62-63 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31367 OF CARLOW Phone:0503/31346 CIGAR DIVAN TULL Y'S TRAVEL AGENCY Newsagent, Confectioner, Tobacconist, etc. TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW Phone:0503/31257 Bring your friends to a musical evening in Carlow's unique GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA Music Lounge each Saturday and Sunday. Phone: 0503/27159. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY, SMYTHS of NEWTOWN CARLOW SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE Builders Providers, General Hardware Tyre Service and Accessories 'THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31414 Phone:0503/31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Far, Sales and Lettings,. Property and Est e Agent. Dinner Dances * Wedding Receptions * Private Parties Agent for the Irish Civil Ser- ce Building Society. Conferences * Luxury Lounge 57 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963. -

M a Y 2020 B Y V Il L a H O T E L S & R E S O R T S May 2021

MAY 2021 MAY 2020 MAY BY BY VILLA HOTELS & RESORTS VILLA HOTELS BY VILLA HOTELS & RESORTS THE SHELL BY VILLA HOTELS & RESORTS 1 View Video Swim with the Mantas At Royal Island Resort & Spa Photo by | @sebaspenalambarri the Maldives - Hanifaru Bay. The hundreds of Manta Ray’s filter bay is one of the world’s largest feeding through the millions of feeding grounds for Manta Rays tiny plankton that congregate Look there’s that come to feed off the large within the bay. This extraordinary number of plankton which gets display of feeding is taken up a a Manta in trapped in the bay during the notch by the incredible somer- months of May – November. Once saults and dancing performed by the call is received, everyone can the majestic Manta’s. We keep our the Bay feel the shared excitement as we hands to ourselves and the flashes jump on the boat prepared to off on our underwater cameras so discover mesmerizing encounters not to disturb the Manta’s. After with Manta Rays in the World snorkelling for around 45 minutes, UNESCO Biosphere Reserve of Baa the guide gives us the sign we all The exciting words that give all Atoll. Hanifaru Bay is located just a least want to see; the signal to get present at Royal Island Resort and short 20-minute boat journey from back on the boat. On the way back Spa the sign that it’s going to be the resort and as we arrive, we are to Royal Island Resort there is an exciting day ahead in beautiful informed that there are hundreds positivity in the air as everyone Baa Atoll. -

Tourism Is Not a Dirty Word Partridge/Galbraith

Tourism is not a dirty word Partridge/Galbraith “Tourism is not a Dirty Word” – the importance of tourism to the sustainability of Botanic Gardens Alison Partridge Going Gardens, UK Introduction The aim of this session was to examine the important and strategic role the tourist industry should be playing in the conservation and sustainability of botanic, and other, gardens. To set the scene we looked at statistics coming out of Canada and the UK. In Canada, visiting a garden ranked 9th on the list of top 20 activities important to visitors. VisitBritain reported that 1/3 of the 31 million visitors in 2012, enjoyed a park or garden. Clearly there is a demand for this touristic product in both markets and yet “Garden Tourism” continues to be classified as a niche market and outside the mainstream marketing focus. The development of the Vancouver Island Garden Trail, on Canada’s west coast, in 2002, was used as an example of how collectively gardens can promote a region, with more visits to each individual property being the result. The success of this project brought garden tourism to the attention of Canadian destination marketing organisations and companies, with the effect of including this product in more traditional marketing efforts, such as adventure tourism, outdoor trourism and eco-tourism. Other examples internationally were held up as the way forward for gardens to increase visitor numbers, and therefore revenue; also, for those with no ticket price, after-gate spending, thereby sustaining their ability to maintain their garden and whatever important research and development they may be seeking to undertake. -

Garden Tourism in Ireland: an Exploation of Product Group Co- Operation, Links and Relationships

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Tourism and Food 2010-01-01 Garden Tourism in Ireland: an Exploation of Product Group Co- operation, Links and Relationships Catherine Gorman Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/tourdoc Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Gorman, C.E. (2010). Garden Tourism in Ireland An Exploration of Product Group - Co-operation, Links and Relationships. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Trinity College Dublin. doi:10.21427/D7TK6S This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Tourism and Food at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Garden Tourism in Ireland An Exploration of Product Group Co-operation, Links and Relationships Catherine E. Gorman PhD 2010 Garden Tourism in Ireland An Exploration of Product Group Co-operation, Links and Relationships A thesis presented to Dublin University by Catherine E. Gorman B.Sc. (NUI) M.Appl.Sc. (NUI) MBS (NUI) In fulfilment of the Requirement of PhD Submitted to Department of Geography, Dublin University, Trinity College Supervisor: Prof. Desmond A. Gillmor 2010 Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this, or any other university. I authorise that the University of Dublin to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. -

The Church of Pentecost General Headquarters Apostles, Prophets

THE CHURCH OF PENTECOST GENERAL HEADQUARTERS APOSTLES, PROPHETS, EVANGELISTS, NATIONAL/AREA HEADS, RECTOR, DEANS AND MINISTRY DIRECTORS’ FASTING AND PRAYER MEETING THEME: I WILL BUILD MY CHURCH SLOGAN: POSSESSING THE NATIONS: I AM AN AGENT OF TRANSFORMATION KEY VERSE: Matthew 16:18: Titus 2:13-14 VENUE: PENTECOST CONVENTION CENTRE – GOMOA FETTEH NEAR KASOA DATE: NOVEMBER 12-17, 2018 CONTENTS 1. Time Table i 2. Overview of Theme 2019/The Purpose of the Church Apostle Eric Kwabena Nyamekye 1-11 3. The Nature of the Church Apostle Dr. Elorm Donkor 12-22 4. Leadership of the Church Apostle Dr. Daniel Walker 23-39 5. The Mission of the Church Apostle Dr. Emmanuel Anim 40-88 6. The Life of the Church Apostle Eric Kwabena Nyamekye 89-98 7. The Marks of the Early Church – Lessons for the Local Church of Pentecost Apostle Yaw Adjei-Kwarteng 99-115 8. The Church and the Christian Home (Possessing the Nations by Possessing the Home) Apostle Ekow Badu Wood 116-128 9. Songs 129-142 THE CHURCH OF PENTECOST - GENERAL HEADQUARTERS APOSTLES, PROPHETS, EVANGELISTS, NATIONAL/AREA HEADS, RECTOR/PRINCIPALS, DEANS AND MINISTRY DIRECTORS’ FASTING AND PRAYER MEETING NOVEMBER 12 - 17, 2018 VISION 2023 THEME: POSSESSING THE NATIONS - EQUIPPING THE CHURCH TO TRANSFORM EVERY SPHERE OF SOCIETY WITH VALUES AND PRINCIPLES OF THE KINGDOM OF GOD THEME 2019: I WILL BUILD MY CHURCH KEY VERSES: Matthew 16:18; Titus 2:13-14 VENUE: PENTECOST CONVENTION CENTRE - GOMOA FETTEH NEAR KASOA DAY/DATE MORNING SESSION AFTERNOON SESSION 10:00 3:45 12:30 – TIME 8:00 – 9:00 9:00 –10:00 - 10:15 - 11:15 11:15–12:15 2:30 – 3:45 – 4:00 – 5.00 5.00 - 6:00 2:30 10:15 4:00 SUNDAY Nov. -

Contestation Over an Island Imaginary Landscape: the Management and Maintenance of Touristic Nature

Contestation over an island imaginary landscape: the management and maintenance of touristic nature Article Accepted Version Kothari, U. and Arnall, A. (2017) Contestation over an island imaginary landscape: the management and maintenance of touristic nature. Environment and Planning A, 49 (5). pp. 980- 998. ISSN 0308-518X doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16685884 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/68321/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16685884 Publisher: Sage All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Contestation over an island imaginary landscape: The management and maintenance of touristic nature Abstract This article demonstrates how maintaining high-end tourism in luxury resorts requires recreating a tourist imaginary of pristine, isolated and unpeopled island landscapes, thus necessitating the ceaseless manipulation and management of space. This runs contrary to the belief that tourism industries are exerting an increasingly benign influence on local environments following the emergence of ‘sustainable tourism’ in recent decades. Rather than preventing further destruction of the ‘natural’ world, or fostering the reproduction of ‘natural’ processes, this article argues that the tourist sector actively seeks to alter and manage local environments so as to ensure their continuing attractiveness to the high-paying tourists that seek out idyllic destinations. -

Ontario Garden Tourism Strategy

ONTARIO GARDEN TOURISM STRATEGY REVISED JULY 8, 2011 Prepared for the Ontario Garden Tourism Coalition The mandate of the Ontario Garden Tourism Coalition is to foster the development of the garden and horticultural experiences located across the province for the purpose of generating incremental tourism trips as a result of the horticultural experiences available. MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS Funding provided by the Government of Ontario ONTARIO GARDEN TOURISM STRATEGY TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................................................2 BACKGROUND....................................................................................................................................................................................3 THE TOURISM INDUSTRY..................................................................................................................................................................3 PROJECT DELIVERABLES ................................................................................................................................................................5 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................................................................................6 -

For Immediate Release Winners of the 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WINNERS OF THE 2019 CANADIAN GARDEN TOURISM AWARDS Victoria, Canada, November 5, 2019 Today at the North American Garden Tourism Conference, in the spirit of the conference theme: “Taking Garden Tourism to the Next Level”, the recipients of the 2019 Garden Tourism Awards were announced. Garden Tourism can be a significant component of a destination’s tourism offering Over 25 million people travel annually in North America to see gardens, and the global market of garden visitors exceeds 250 million. Research indicates that 46 per cent of garden visits result in an overnight stay, and the demographic of garden visitors includes all age cohorts. Destination British Columbia estimates the value of garden tourism in the Province of British Columbia alone exceeds $300 million annually. Latest research in the UK show that Garden Tourism generates almost £3 billion of economic impact. Gardens not only have a significant economic impact but also enhance the tourist experience of a destination, while providing positive social and health benefits. Garden Tourism Awards The Garden Tourism Awards are presented to organizations and individuals who have distinguished themselves in the development and promotion of garden experiences as tourism attractions and motivators. The awards are proudly supported by the Canadian Garden Council, the American Public Gardens Association and the Mexican Association of Botanical Gardens and sponsored by the Canadian Nursery Landscape Association. The 2019 Canadian Garden Tourism Award winners are . The Canadian Garden Council is honoured to announce the following award recipients: 1. Garden of the Year Niagara Parks Botanical Gardens, ON Sponsored by: Canadian Nursery Landscape Association 2. -

Garden Design and Tourism

House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee Garden design and tourism Fourteenth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 16 July 2019 HC 2002 Published on 22 July 2019 by authority of the House of Commons The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) (Chair) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Clive Efford MP (Labour, Eltham) Julie Elliott MP (Labour, Sunderland Central) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Julian Knight MP (Conservative, Solihull) Ian C. Lucas MP (Labour, Wrexham) Brendan O’Hara MP (Scottish National Party, Argyll and Bute) Jo Stevens MP (Labour, Cardiff Central) Giles Watling MP (Conservative, Clacton) The following Member was also a member of the Committee during the inquiry: Rebecca Pow MP (Conservative, Taunton Deane) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/copyright. Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/dcmscom and in print by Order of the House.