Contestation Over an Island Imaginary Landscape: the Management and Maintenance of Touristic Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here You Will Enjoy a Lunch Pack Which Includes Water and Soft Drinks

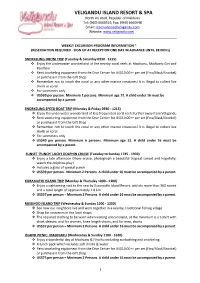

VELIGANDU ISLAND RESORT & SPA North Ari Atoll, Republic of Maldives Tel: (960) 6660519, Fax: (960) 6660648 Email: [email protected] Website: www.veligandu.com WEEKLY EXCURSION PROGRAM INFORMATION * (RESERVATION REQUIRED - SIGN UP AT RECEPTION ONE DAY IN ADVANCE UNTIL 18:00hrs) SNORKELING DHONI TRIP (Tuesday & Saturday 0930 - 1215) v Enjoy the underwater wonderland of the nearby coral reefs at Madivaru, Madivaru Giri and Rasdhoo v Rent snorkeling equipment from the Dive Center for US$10.00++ per set (Fins/Mask/Snorkel) or purchase it from the Gift Shop v Remember not to touch the coral or any other marine creatures! It is illegal to collect live shells or coral v For swimmers only v US$30 Per Person. Minimum 2 Persons. Minimum age 12. A child under 16 must be accomPanied by a Parent. SNORKELING SPEED BOAT TRIP (Monday & Friday 0930 - 1215) v Enjoy the underwater wonderland of less frequented coral reefs further away from Veligandu v Rent snorkeling equipment from the Dive Center for US$10.00++ per set (Fins/Mask/Snorkel) or purchase it from the Gift Shop v Remember not to touch the coral or any other marine creatures! It is illegal to collect live shells or coral v For swimmers only v US$40 Per Person. Minimum 6 Persons. Minimum age 12. A child under 16 must be accomPanied by a Parent. SUNSET ‘PUNCH’ LUCKY DOLPHIN CRUISE (Tuesday to Sunday 1745 - 1930) v Enjoy a late afternoon Dhoni cruise, photograph a beautiful tropical sunset and hopefully, watch the dolphins play! v Includes a glass of special punch v US$39 Per Person - Minimum 2 Persons. -

Carlow College

- . - · 1 ~. .. { ~l natp C u l,•< J 1 Journal of the Old Carlow Society 1992/1993 lrisleabhar Chumann Seanda Chatharlocha £1 ' ! SERVING THE CHURCH FOR 200 YEARS ! £'~,~~~~::~ai:~:,~ ---~~'-~:~~~ic~~~"'- -· =-~ : -_- _ ~--~~~- _-=:-- ·.. ~. SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL- 9-13 DUBLIN STREET ~ P,•«•11.il H,,rd ,,,- Qua/in- O'NEILL & CO. ACCOUNTANTS _;, R-.. -~ ~ 'I?!~ I.-: _,;,r.',". ~ h,i14 t. t'r" rhr,•c Con(crcncc Roonts. TRAYNOR HOUSE, COLLEGE STREET, CARLOW U • • i.h,r,;:, F:..n~ r;,,n_,. f)lfmt·r DL1nccs. PT'i,·atc Parties. Phone:0503/41260 F."-.l S,:r.cJ .-\II Da,. Phone 0503/31621. t:D. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD. Jewellers, ·n~I, Fashion Boutique, Fuel Merchant. Authorised Ergas Stockist ·~ff 62-63 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31367 OF CARLOW Phone:0503/31346 CIGAR DIVAN TULL Y'S TRAVEL AGENCY Newsagent, Confectioner, Tobacconist, etc. TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW Phone:0503/31257 Bring your friends to a musical evening in Carlow's unique GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA Music Lounge each Saturday and Sunday. Phone: 0503/27159. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY, SMYTHS of NEWTOWN CARLOW SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE Builders Providers, General Hardware Tyre Service and Accessories 'THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31414 Phone:0503/31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Far, Sales and Lettings,. Property and Est e Agent. Dinner Dances * Wedding Receptions * Private Parties Agent for the Irish Civil Ser- ce Building Society. Conferences * Luxury Lounge 57 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963. -

M a Y 2020 B Y V Il L a H O T E L S & R E S O R T S May 2021

MAY 2021 MAY 2020 MAY BY BY VILLA HOTELS & RESORTS VILLA HOTELS BY VILLA HOTELS & RESORTS THE SHELL BY VILLA HOTELS & RESORTS 1 View Video Swim with the Mantas At Royal Island Resort & Spa Photo by | @sebaspenalambarri the Maldives - Hanifaru Bay. The hundreds of Manta Ray’s filter bay is one of the world’s largest feeding through the millions of feeding grounds for Manta Rays tiny plankton that congregate Look there’s that come to feed off the large within the bay. This extraordinary number of plankton which gets display of feeding is taken up a a Manta in trapped in the bay during the notch by the incredible somer- months of May – November. Once saults and dancing performed by the call is received, everyone can the majestic Manta’s. We keep our the Bay feel the shared excitement as we hands to ourselves and the flashes jump on the boat prepared to off on our underwater cameras so discover mesmerizing encounters not to disturb the Manta’s. After with Manta Rays in the World snorkelling for around 45 minutes, UNESCO Biosphere Reserve of Baa the guide gives us the sign we all The exciting words that give all Atoll. Hanifaru Bay is located just a least want to see; the signal to get present at Royal Island Resort and short 20-minute boat journey from back on the boat. On the way back Spa the sign that it’s going to be the resort and as we arrive, we are to Royal Island Resort there is an exciting day ahead in beautiful informed that there are hundreds positivity in the air as everyone Baa Atoll. -

A Case-Study of a Beach Resort in the Maldives

WATER FOOTPRINT OF COASTAL TOURISM FACILITIES IN SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING STATES: A CASE-STUDY OF A BEACH RESORT IN THE MALDIVES by Miguel Orellana Lazo A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Landscape Architecture) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2013 © Miguel Orellana Lazo, 2013 Abstract Research on climate change indicates that the risk of water scarcity at many remote tourist destinations will increase in the next few decades. Tourism development puts strong pressure on freshwater resources, the availability of which is especially limited in remote areas. At locations with no access to conventional water sources, tourism facilities require supply alternatives, such as desalinated or imported water, which implies elevated energy demands and carbon emissions. In this context, a shift in the way freshwater use is assessed is crucial for moving toward a more sustainable model of water management for tourism development. This research adapts the Water Footprint framework to the design of tourism facilities and explains how and why this is a promising model for water accounting in isolated locations. Defined as 'an indicator of freshwater resources appropriation', the Water Footprint concept was introduced by Hoekstra in 2002. This methodology goes beyond the conventional direct water use assessment model, upon which most common benchmarking systems in sustainable tourism are based. Measuring the water footprint of a tourism facility allows operators and design teams to understand the environmental and socio-economic impacts associated with its direct and indirect water uses. -

Hotel Information

Hotel Information Marco Island Marriott Beach Resort Hotel Reservations and Room Rate 400 South Collier Boulevard The room rate, which is subject to the current state and Marco Island, FL 34145 USA local taxes per room, per night, is $339.00 single/double 1.239.394.2511 occupancy. A service charge of $6.00 per room, per day will be added to cover services provided by the www.marcoislandmarriott.com Bell Staff and Housekeeping. In order to make your hotel reservation you must first register for the meeting with the IADC. Once registered, the IADC will send you a link to the resort’s secured reservation website along with your registration confirmation that will allow you to secure a hotel room at the resort. Online reservations, along with a one night room and tax deposit, must be received by January 12, 2015. An individual’s deposit is refundable to that individual if the resort receives notice of cancellation at least seven days prior to scheduled arrival. Individual guest room reservations canceled after this time will forfeit the one night deposit. Exceptions will be made for cancellations, in writing, due to medical emergencies or a required appearance in trial. Availability of rooms Come kick off your shoes and explore paradise found at the group rate is subject to the IADC room block and at this one-of-a-kind Florida resort, now celebrating for reservations made by January 12, 2015 when unused the completion of over $250 million in renovations and rooms will be released. Reservation requests received redesign that has infused every moment with the spirit after the room block has been fully reserved or after the 20 of Balinese beauty, hospitality, and well-being - and release of unused rooms on January 12, 2015 will be added even more wondrous experiences to this already accepted on a space available basis at the group rate. -

Glenn Roberts Anson Mills Columbia, South Carolina *** Date

Glenn Roberts Anson Mills Columbia, South Carolina *** Date: November 1, 2017 Location: Columbia, South Carolina Interviewer: Kate Medley Transcription: Technitype Transcripts Length: One Hour and 47 Minutes Project: Southern Grains Glenn Roberts | 1 Kate Medley: I’ll kick things off by saying this is Kate Medley interviewing Glenn Roberts behind the—what car wash? [0:00:06.7] Glenn Roberts: Constan. [0:00:07.6] Kate Medley: Constan Car Wash, at the world headquarters of Anson Mills in Columbia, South Carolina. It’s November 1st, 2017. Then I’ll turn it to you and get you to introduce yourself. [0:00:23.6] Glenn Roberts: I’m Glenn Roberts. I’m in Columbia, South Carolina, today at the home base for Anson Mills, which is located behind Constan Car Wash in beautiful Columbia, South Carolina, and we’re humble and not even proud. [0:00:41.5] Kate Medley: And what’s your birth date? [0:00:42.8] Glenn Roberts: I was born January 14th, 1948, so I’m a lazy Capricorn. [0:00:53.2] © Southern Foodways Alliance | www.southernfoodways.org Glenn Roberts | 2 Kate Medley: Introduce us to what is Anson Mills. What do y’all do? [0:00:57.2] Glenn Roberts: Anson Mills, succinctly, is a group of farmers that come together with some real smart women, Catherine Schopfer, my partner, being the head of that, Kay Rentschler, my darling wife, being the second creative person in that net. We’re all a group of people who have a shared common goal to feed people really, really great food. -

Bodge Island Repair in the Maldives 2008.Pdf

IN THIS ISSUE: Challenges and impacts associated with coastal megareclamation developments Island repair in the Maldives Scale effects of megaprojects Coastal megacities and hazards: Challenges and opportunities VOLUME 76 • NO. 4 • FALL 2008 Journal of the American Shore & Beach Preservation Association Bodge, K. & Howard, S., “Island Repair in the Maldives”. Shore & Beach, American Shore & Beach Preservation Assn. Vol. 76, No. 4; pp 17-24. Fall 2008. Island Repair in the Maldives By Kevin R. Bodge, Ph.D., P.E. Vice President, Olsen Associates, Inc. 4438 Herschel Street, Jacksonville, FL 32210 USA [email protected] Steven H. Howard, P.E. Coastal Engineer, Olsen Associates, Inc. 4438 Herschel Street, Jacksonville, FL 32210 USA [email protected] ABSTRACT After substantial expansion and re-shaping of a resort island in the Maldives by dredging, the island’s new shoreline rapidly eroded and nearshore water circulation declined. To address these problems in time for the new resort to open, over 50 different rock structures were designed and constructed to create 19 distinct beaches totaling 4 km in length, and a channel was cut to sever the island and partially restore tidal flow. The authors completed the site studies and designs while living on-island amidst frenetic resort construction during several weeks in the summer of 2004. The works were completed that autumn, and thereafter withstood impact from the December 2004 tsunami. To-date, the project repairs have successfully stabilized the beaches and improved water circulation, per the design predictions. INTRODUCTION In early 2004, one of our firm’s long-time clients was the first to begin developing a large hotel resort on the new “palm shaped” islands being created in Dubai. -

Economic Crisis, International Tourism Decline and Its Impact on the Poor Economic Crisis, International Tourism Decline and Its Impact on the Poor

Economic Crisis, International Tourism Decline and its Impact on the Poor Economic Crisis, International Tourism Decline and its Impact on the Poor Copyright © 2013, World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and International Labour Organization (ILO) UNWTO, 28 May 2013, for International Labour Organization, for internal use, only. Copyright © 2013, World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and International Labour Organization (ILO) Economic Crisis, International Tourism Decline and its Impact on the Poor UNWTO ISBN: 978-92-844-1443-7 (printed version) ISBN: 978-92-844-1444-4 (electronic version) ILO ISBN: 978-92-2-126985-4 (printed version) ISBN: 978-92-2-126986-1 (electronic version) Published and printed by the World Tourism Organization, Madrid, Spain. First printing: 2013 All rights reserved The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinions whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Tourism Organization and International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities or concerning the de- limitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the Secretariat of the World Tourism Organization or the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the Secretariat of the World Tourism Organization or the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Sustainability Expectations

KomandooMALDIVES SUSTAINABLE LIFESTYLE [email protected] . [email protected] . www.komandoo.com In delivering this commitment, Komandoo Island Resort will endeavor to: • Meet or exceed applicable environmental legislations, environmental standards and best practices • Value and preserve the natural and cultural heritage of our properties, thus enabling our guests to enjoy an authentically local experience STATEMENT ON SOCIAL • Promote efficient use of materials and resources across our property, especially water and energy AND ENVIRONMENTAL PARTICIPATION • Work diligently to minimize our waste stream by reusing, recycling and conserving natural Resources, particularly through energy and water conservation Maldives is a delicate nation which is founded on live coral reefs enclosed with 99% of • Set sound environmental and social objectives and targets, integrate a process of review and Issue progress reports on a periodic basis ocean. This delicate balance has been well maintained until the world discovered it as an exotic destination for tourism. What began as diving destination in 1972 has now grown • Continually identify opportunities for improvement of our to be a multifaceted tourist fascination. environmental management system Like any other destination with such a discovery, blessings do come with their own bur- • Promote awareness and educate Champions (Komandoo team members) on dens. Sure, enough the blessing of tourism on Maldives has come with its flip side – the environmental issues and sustainable working practices pressure on the nature, when the nation was not yet prepared for such an onslaught with- in such a short period of time. • Engage our guests, Champions, suppliers, contractors and the local community in our initiatives to preserve the environment and consider their opinions/ feedback when This has laden the resorts with the onus to be mindful of the delicateness of nature and setting our Environmental programs and procedures environment. -

EXCURSIONS Nika Islan D Reso Rt & Spa

PRICE LIST EXCURSIONS Nika Islan d Reso rt & Spa SNORKELING TOUR IN NIKA AREA The Maldives is famous for its underwater beauty with its pristine corals, the colorful reef fish as well as the impressive pelagic creatures. Nika is most fortunate to be located in just few minutes away from the some of the best diving and snorkeling sites of North Ari Atoll. (Accompanied snorkeling trip by dhoni in the area of Nika Resort) Duration: 2 hours 11:00- 13:00 Minimum:4 pax $ 27 per person SNORKELING WITH MARINE BIOLOGIST Duration: 1 hours 11:00- 12:00 Minimum: 1pax $ 15 per person DISCOVERY OF FARAWAY REEFS Join this excursion where you will have a chance to explore vibrant corals and underwater life around the Indian Ocean reefs. Two beautiful sites where spectacular sceneries and colorful fishes will make you become a part of them. Accompanied snorkeling trip by speed boat to the far away reefs of Kandholhudhoo /Bathala/ Beyru Madivaru /Fesdhoo) Duration: 2 hours 11:00 – 13:00 Minimum:4 pax $ 94 per person (1reef) 3 hours 10:00 – 13:00 Minimum:4 pax $ 127 per person (2 reefs) $ 750 Private MANTA SEEKING The Maldives are great for sighting manta rays seasonally, though it is not uncommon to see them throughout the year as well. An experience not to be missed! (Accompanied snorkeling trip by speed boat at the closest Manta point) Duration: 2 hours 11:00 – 13:00 Minimum:4 pax $ 94 per person $ 750 Private WHALE SHARK TRIP Ocean Reef located 60 minutes by Dhoni is another great snorkeling site where whale sharks are spotted seasonally. -

2020 Special Alumni Hotel Information Reunions Are a Time-Honored

2020 Special Alumni Hotel Information Reunions are a time-honored tradition that celebrate the gathering of alumni. Whether the reunion takes place during Alumni Week or another time during the year, we are always happy to welcome our alumni back to Hawai‘i. As a benefit to our alumni, we have negotiated special hotel rates with Marriott Hotel & Resorts, Outrigger Hotels & Resorts, Prince Resorts Hawaii and Ala Moana Hotel by Mantra. 2020 Punahou Alumni rate information is provided below. Marriott Hotels & Resorts Effective Dates: January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020 Rates are subject to blackout dates. Reservations: Individual reservations can be made through your preferred travel agency or our reservations department. The Reservations Center. Call 808.921.4560 or 866.716.8140 Ask for specific rate plan: LOCAL COMPANIES when making reservations. Please use this direct booking link: Book your corporate rate for Local Companies To access your Local Companies Corporate Rates directly. The Cluster Code L6C can also be used on our property websites by inputting this into the “Corporate/Promo/Set#” search box will also return the Local Companies Corporate Rates. Participating properties: Moana Surfrider, A Westin Resort & Spa, Waikiki Beach Historic Banyan, Starting at $329 Historic Banyan Ocean, Starting at $399 Tower City, Starting at $359 The Royal Hawaiian, a Luxury Collection Resort, Waikiki Historic Room, Starting at $385 Historic Garden, Starting at $425 Mailani Tower Ocean, Starting at $555 Sheraton Waikiki City View, Starting at $329 Partial Ocean, Starting at $359 Oceanfront, Starting at $389 Sheraton Princess Kaiulani Kaiulani Room/Tower City, Starting at $195 Partial Ocean View, Starting at $220 *Please note these Corporate Rates are based upon hotel availability and may not always be available. -

(1991) “Spatial Behavior in a Bahamian Resort,” Annals of Tourism Research, 18(2): 251-268

Spatial Behavior in a Bahamian Resort By: Keith Debbage Debbage, K. (1991) “Spatial Behavior in a Bahamian Resort,” Annals of Tourism Research, 18(2): 251-268. Made available courtesy of Elsevier: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/016073839190008Y ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Elsevier. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: The purpose of this study is to understand better the spatial behavior of tourists visiting spatially confined resort destinations. Based on a time-budget study of the intradestination travel patterns of 795 tourists visiting Paradise Island (Bahamas), the travel behavior of tourists was found to be heterogeneous. The spatial equivalent of the allocentric tourist seemed more likely to venture beyond the Paradise Island resort area during their stay. Only the psychocentric tourist seemed reluctant to leave the island under any conditions. In the context of international resort tourism, the space-time constraints are found to be more important than the socioeconomic descriptors in explaining the different typologies of spatial behavior. Résumé Le comportement dans l'espace dans une station balnéaire bahamienne. Le propos de la présente étude est de contribuer á la compréhension du comportement dans l'espace des touristes qui visitent des destinations de vacances dont le terrain est limité. Selon une étude de l'utilisation du temps de 795 touristes dans leurs mouvements á l'intérieur de leur lieu de destination, dans ce cas l'Lle du Paradis (Bahamas), le comportement des touristes dans l'espace est hétérogène.