Compiling Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jalsa-UK-Booklet-2019.Pdf

The Jalsa Salana The Annual Convention (Jalsa Salana) of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community UK is a unique event that brings over 35,000 participants from more than 90 countries to in- crease religious knowledge and promote a sense of peace in society. Eminent speakers discuss a range of religious topics and their relevance to contemporary society. Addi- tionally, a number of parliamentarians, civic leaders and diplomats from different countries also address the gather- ing and underline the conventions objective of enhancing unity, understanding and mutual respect. A special feature of this convention is that it is blessed by the presence of His Holiness Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the Head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He address- es the convention over each of the three days, providing an invaluable insight into religious teachings and how they are a source of guidance for the world today. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (Peace be upon him) The Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (peace be upon him) of Qadian, India. He claimed under divine guidance to be the Promised Messiah and Imam Mahdi, whose advent was awaited by all the religions of the world. He championed the peaceful teachings of Islam, revived the Faith with a sense of purpose and inspired his followers to build a strong bond with God and to serve humanity with a selfless spirit of compassion and humility. The community is now established in more than 210 coun- tries and it spearheads an international effort to promote the true message of Islam and of service to humanity. -

An E-Magazine for Nasirat-Ul-Ahmadiyya UK |7Th Edition|

AyeshaAn e-magazine for Nasirat-ul-Ahmadiyya UK |7th Edition| Content 3 Holy Qur’an: Surah Al-Hashr 4 Hadith: Envy 5 Writings of the Promised Messiah (as): The Holy Qur’an is a perfect guidance 6 Huzoor’s (aba) Quotes: Living as a Muslim woman in modern-day society 8 A personal account by Abid Khan Sahib: Europe September-October 2019 part1 10 Books of the Promised Messiah (as): Barahin-e- Ahmadiyya Volume 1 11 Book corner: Hazrat Mariyah Qibtiyya (ra) “Mother of the believers” 12 Career Corner: Specialising as a counselling therapist 13 Travel: Marrakesh 15 Poem: Khilafat 16 Inspiring role model: The slave girl who became the mother of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw) 18 Inspiring stories: Hazrat Bilal (ra) 19 Drawing: Mubarak Mosque 20 Recipe: Marbel Cake 21 My amzing body: Eyelashes 23 Nasirat articles: 1) The existence of God 25 2) How I overcame my fear of bees 26 Upcycling: 1) NHS model 2) Surgical Masks 28 Funology: Riddles THE HOLY QUR’AN The Holy Qur’an He is Allah, and there is no God beside Him, the Sovereign, the Holy One, the Source of Peace, the Bestower of Security, the Protector, the Mighty, the Subduer, the Exalted. Holy is Allah far above that which they associate with Him. Commentary God is the King Who is free from every fault, defect, or deficiency. He is the Source of all peace, and the Granter of safety and security. He is Guardian overall, overcoming every power, the Mender of every breakage and the Restorer of every loss; and He is above every need and is the Besought of all. -

Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad Said: “Many of One’S Social Interactions Are Carried out As a Result of One’S Emotions Or Hab- Its

He is Allah, and there is no God beside Him, the Sovereign, the Holy One, the Source of Peace, the Bestower of Security, the Protector, the Mighty, the Subduer, the Exalted. Holy is Allah far above that which they associate with Him. More Info Abu Dharr reported: The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “Allah Almighty says: Whoever comes with a good deed will have the reward of ten like it and even more. Whoever comes with an evil deed will be recompensed for one evil deed like it or he will be for- given. Whoever draws close to me by the length of a hand, I will draw close to him by the length of an arm. Whoev- er draws close to me the by length of an arm, I will draw close to him by the length of a fathom. Whoever comes to me walking, I will come to him running. Whoever meets me with enough sins to fill the earth, not associating any idols with me, I will meet him with as much forgiveness.” (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2687) More Info Iqtebas Saying of The Promised Messiah as Our paradise lies in our God. Our highest delight is in our God for we have seen Him and found ever- beauty in Him. This wealth is worth procuring though one might have to lay down one’s life to procure it. This ruby is worth purchasing though one may have to lose oneself to acquire it. O ye, who are deprived! Hasten to this fountain as it will satiate you. -

Virginia Mosque Attack.Feb.12

LONDON, 1 February 2012 PRESS RELEASE MUSLIMS RESPOND TO MOSQUE ATTACK IN VIRGINIA Attack will not deter Ahmadi Muslims from completing the Mubarak Mosque The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat condemns the vandalism committed on their new Mubarak Mosque in Chantilly, Virginia, on 29th January 2012. In this senseless act, vandals destroyed nearly every window on the first floor of the new construction, causing an estimated $60,000 worth of damage. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat hopes that this remains an isolated incident. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat is the oldest Muslim organisation in the United States and has spent decades presenting the true and peaceful message of Islam to the American public. It has thousands of members spread across the United States who are propagating a message of peace, tolerance and loyalty. The President of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat in the USA, Dr Ahsan Zafar said “As Muslims who believe in the Promised Messiah, Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, we are a tolerant and patient people and we will continue with our work while the police will do their job. This Mosque will be a source of education, peace, love and understanding. And we will not let isolated cases of intolerance get in the way.” The international Press Secretary of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, Abid Khan, in London, said: “The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat is based in 200 countries and wherever Ahmadi Muslims build mosques they are signs of peace, unity and inclusion. It is a real shame that our new mosque in Virginia has been attacked in this way. We believe that all places of worship, regardless of religion, should be respected.” The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat is grateful for the outpouring of support for the Mosque from the vast majority of the surrounding community. -

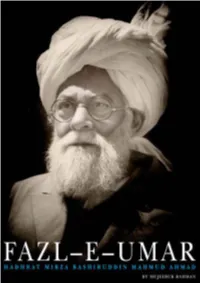

Fazl-E-Umar.Pdf

FAZL-E-UMAR The Life of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad Khalifatul Masih II [ra] First published in the UK in 2012 by Islam International Publications Copyright © Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 2012 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. For legal purposes the Copyright Acknowledgements constitute a continuation of this copyright page. ISBN: 978-0-85525-995-2 Designed and distributed by Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK Author: Mujeebur Rahman Printed and bound by Polestar UK Print Limited CONTENTS Letter from Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad [atba] 1 Foreword 3 Comments by Sadr Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 9 PART 1 15 Early childhood and parental training 17 Education 41 Public speaking and writing 55 Childhood interests, games and pastimes 63 Circle of contacts 75 Belief in the truth of his father and its consequences 80 Ever–growing faith in the Promised Messiah [as] 88 The death and burial of the Promised Messiah [as] 90 Historic pledge of Hadhrat Sahibzada Mirza Mahmud Ahmad 98 PART 2 103 Establishment of Khilafat in the Ahmadiyya Movement 105 Efforts to support and strengthen the institution of Khilafat 110 PART 3 143 Khilafat of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad [ra] 144 Independence -

English Section

An informational, literary, educational, and training magazine of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, USA January-February 2016 The Ahmadiyya GAZETTE USA Muslih Mau'ud Edition Inauguration Ceremony of the Nusrat Mosque Extremists recruit by distorting Islam. Coon Rapids, Minnesota But we can STOP them. And YOU can help. Behold! a light cometh, a light anointed by God Tabligh Activities in Merida, Mexico with the perfume of His pleasure. We shall pour our spirit into him and he will be sheltered under the shadow of God. He will grow rapidly in stature and will be the means of procuring the release of those held in bond- age. His fame will spread to the ends of the earth and peoples will be blessed through him. Support our CAMPAIGN against EXTREMISTS www.TrueIslam.com WAQFE NAU BOYS’ ANNUAL TRIP TO JAMIA AHMADIYYA, CANADA Register online at www.waqfenau.us APRIL 8 - 10, 2016 (FRI - SUN) Experience a full day at the Jamia along with sports competitions and sightseeing APPLY FOR ADMISSION TO JAMIA AHMADIYYA, CANADA Jamia Ahmadiyya Canada is seeking US applicants for admission into the 7-year Shahid degree program beginning in fall, 2016. The applicants for admission must fulfill the following prerequisites: The applicant must be between 17 and 20 years of age. The applicant must have finished high school. The applicant must apply for Waqfe Zindagi (life dedication) also. The applicant must be able to recite the Holy Quran correctly. For detailed information, please contact [email protected] or call (706)- 860-1629. Hafiz Samiullah Chaudhary National Secretary Waqfe Nau, USA The Ahmadiyya Gazette USA Vol. -

Nov – Dec 2017

An informational, literary, educational, and training magazine of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, USA : The Ahmadiyya : GAZETTENovember-December 2017 USA “One of the most phenomenal parts of my career has been coming to Jalsa Salana and speaking. You are a remark- able community. I can think of no one I’d rather call a neigh- bor than an Ahmadi. You are patriotic, hard-working, be- lieve in family and care for our neighbors. You are phenom- enal ambassadors for Islam” Nick Miccarelli, Member, Pennsylvania House of Representatives Comments during 2017 Jalsa Salana USA Vol. 69. No. 11-12. — Ṣafar/Rabī‘-ul-Awwal 1439 H — Nubuwwat/Fatḥ 1396 HS — November/December 2017 Patron: Sahibzada Dr. Mirza Maghfoor Ahmad Table of Contents Amīr Jamā‘at Aḥmadiyya USA Editorial Advisors: ISLAM—THE TRUE RELIGION ............................................ 2 Mohammed Zafarullah Hanjra. Syed Shamshad Ahmad Nasir. ABOUT PRAYERS ............................................................... 3 Editor: Syed Sajid Ahmad Assistant Editor: Dr. Mahmud Ahmad Nagi DR NASIM REHMATULLAH ................................................ 3 Editorial Team: Haji Dhul-Waqar Yaqub. Dr. Ijaz Tahir. Saiyed Burhan Qaderi. THE LIVING SIGN OF DIVINE HELP ..................................... 4 Dr Wajeeh Bajwa. Hasan Hakeem. Tariq Sharif. Sahibzadah Tahir Latif. Naveed Ahmed Malik, DC. KHILĀFAT NEWS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS ........................ 5 Design Lead: Latif Ahmed Graphics Team: Rashid Arshad. Sumera Ahmad. WEEKLY GUIDANCE FROM ḤAḌRAT KHALĪFATUL-MASĪḤ V Naveed Malik, Silver Spring. -

The Commentary of Al-Qasidah

The Commentary of al-Qasidah ňIJČ ٖ ◌ D E 3 % !"#$" &'()*+ Urdu cover title of the book printed by Ash-Shirkatul-Islamiyyah Limited, Rabwah The Commentary of al-Qasidah ňIJČ The English translation and commentary of an Arabic poem by the Promised Messiahas, in praise of the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa Commentary by Maulana Jalal-ud-Din Shams ň IJČ ThTheThee Commentary of alal----QaQQaaQasiiiddaahhdah (((An(AAnnAn English rendering of ‘‘SharSShhaarrSharhhhululul-ul---QaQQaaQasisisiddaahhdah’)dah’)’)’) Written by Hadrat Maulana Jalal-ud-Din Shams English Translation from Urdu by Falah-ud-Din Shams Copyright 2013 by Islam International Publications Ltd. First published in U.K. in 2013 Published by Islam International Publications Ltd. ‘Islamabad’, Sheephatch Lane Tilford, Surrey GU10 2AQ Printed at Raqeem Press Islamabad, Tilford, Surrey ISBN 978-1-84880-090-8 Contents System of transliteration ........................................................................ ix Foreword ............................................................................................ xiii Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 Introduction to Al-Qasidah ............................................. 5 Thei Qas dah with Translation ........................................ 7 Commentary of the Qasidah ......................................... 25 The Beloved In The Eyes of The Lover ..................................... 25 Exceeding All Others in Love ..................................................... -

Muslim Marriage and Divorce

Muslim Marriage and Divorce Contents Page Marriage 3 What is a Muslim Marriage? 4 Marriage Gift (Mahr) 4 What can the marriage contract conditions include? 6 Are witnesses required and who can they be? 7 Do women require a guardian (wali) to get married? 8 Who can conduct marriage ceremonies? 9 What are the conditions of polygamy? 10 Are temporary marriages allowed? 11 Can Muslim women marry non-Muslim men? 13 What are Legally Valid Marriages? 14 What are Legally Invalid Marriages? 15 How to Ensure Marriages Conducted in the UK are Legally Recognised? 17 Divorce 18 About Shariah Councils 19 Grounds For Divorce 20 Permissibility of Divorce in Islam 22 Who Can Preside Over Divorce Cases? 23 Waiting Period (Iddah) 24 Different Methods for Dissolving Marriage in Islam 26 Divorce by Social Media 30 Does Conversion of Faith Dissolve a Marriage? 30 Can a Civil Divorce be a Valid Islamic Divorce? 31 Islamic Divorce Process 32 Using Contract Law to Claim Mahr 35 Civil Divorce 36 Civil Divorce Process 39 Useful Links 41 Legal Aid 41 Annulment of a Marriage 42 Foreign Divorce 43 Cost of Divorce 44 Shariah Divorce Services 46 Marriage What You Need to Know “The information will help Muslim women be more informed about their rights and practices in relation to marriage. We also highlight the consequences of being in marriages that are not legally recognised under laws in the UK and provide advice on the steps that can be taken to ensure women are in a legally valid marriage.” 3 What is a Muslim Marriage? Although a Muslim marriage ceremony may have religious component, it is a civil contract that makes the sexual relationship lawful under Muslim law. -

Ayesha Magazine

Content 3 The Holy Qur’an: Surah Al-Hadid 4 Hadith: Forgiveness 5 Writings of the Promised Messiah (as): The blessings of Prayer 6 Huzoor’s (aba) Quotes: Importance of prayer 7 A Personal account by Abid Khan Sahib: Covid-19 Lockdown 8 Book Corner: Hazrat Mariyah Qibtiyyah (ra) 10 The Holy Qur’an on Aliens: Life beyond earth 12 Did you know!: Did you know... 13 Q&A Corner: Q&A with beloved Huzoor (aba) 14 Discussing Social Media: Pros & Cons of Social Media 15 Discussing Solar Panels: Solar Panels & Renewable Energy 17 Inspirational Women: Umme Musa 20 Just baked: Mac and Cheese Recipe 21 Nasirat Articles: 1) Northern Ireland Jama’at 2) Embracing Disability 23 My Doc and I: With Dr Basma 26 Poetry: 1) 2020 2) Honesty 28 Creative Story: A slice of Kinza’s life 29 Riddled with Games: Riddles & Etymology 30 Quizzing Master: New Quizzes 31 What do these phrases mean?: Common English phrases & Idioms 32 Answers... 33 Competition Announcement THE HOLY QUR’AN Surah Al-Hadid He it is Who created the heavens and the earth in six periods, then He settled Himself on the Throne. He knows what enters the earth and what comes out of it, and what comes down from heaven and what goes up into it. And He is with you wheresoever you may be. And Allah sees all that you do. (Chapter 57, Verse 5) Commentary The six phases of evolution are referred in this verse. These may be ether, cloud of dust and gas, electrons, minerals, plants and animals. -

Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (V): Making Sense of Libya

POPULAR PROTEST IN NORTH AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST (V): MAKING SENSE OF LIBYA Middle East/North Africa Report N°107 – 6 June 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION: THE UPRISING .............................................................................. 1 II. THE NATURE OF QADDAFI’S REGIME ................................................................... 6 A. THE EARLY YEARS ...................................................................................................................... 6 B. THE JAMAHIRIYA AND THE ROLE OF IDEOLOGY ........................................................................... 7 C. THE FORMAL POLITICAL SYSTEM ................................................................................................ 8 D. INFORMAL POWER NETWORKS................................................................................................... 10 1. The Men of the Tent .................................................................................................................. 10 2. The Revolutionary Committees Movement ............................................................................... 10 3. Tribes and “Social People’s Leaderships” ................................................................................. 11 E. QADDAFI’S FAMILY ................................................................................................................... 12 F. THE ROLE OF PATRONAGE -

January-March 2020 USA

An informational, literary, educational, and training magazine of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, USA : The Ahmadiyya : GAZETTEJanuary-March 2020 USA ۡ ۡ ۤۡ ۡ ۡ ۡ ۤۡ ۡ ۡ ۡ ۡ رب اوزع ۡن ان اشکر نعمتک الیَ ۡت انعمت عل و ع یل و ِّاِلی و ان اعمل صال ًحا ت ۡر یض ہ ِّی َ ِّ ِّ َ َ ُ ِّ َ َ َ ِّ َ َ َ َ َ یَ َ َ یَ َ َ َ َ ِّ َ ُ َ ۡ َۡ ۡ َۡ َ َۡ ۡ ۡ َ و اص ِّح ِۡف ر ۡ ِترؕ ۡت تُ ِّا ۡ ا توت ِّالِک و ِّا ۡ ا ِّ الم ِّح ِّم َ َ ِّ ِّ ُ یِّ یَ ِّ ِّی ُ ُ َ َ َ ِّی َ ُ َ ‘My Lord, grant me the power that I may be grateful for Thy favour which Thou hast bestowed upon me and upon my parents, and that I may do such good works as may please Thee. And make my seed righteous for me. I do turn to Thee; and, truly, I am of those who submit to Thee.’ (Al-Ahqaf, 46:16) Respected Ameer Sahib Jama’at-e-Ahmadiyya, USA. Assalamo Alaikum wa Rehmatullah. You have requested for a message to Jama’at-e-Ahmadiyya USA, expressing gratitude to Allah on the completion of 100 years, and to celebrate the Centennial of the USA Jamaat. Exactly 100 years ago today, on February 15, Hazrat Mufti Muhammad Sadiq sahib (rz) arrived there with the message of the Promised Messiah (as) and the spirit and enthusiasm with which he worked, and many virtuous souls entered the fold of Islam Ahmadiyyat, unfortunately their progenies went far away from Ahmadiyyat, and the Jama’at could not retain them.