Your Unpublished Thesis, Submitted for a Degree at Williams College and Administered by the Williams College Libraries, Will Be Made Available for Research Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

For All the Attention Paid to the Striking Passage of Thirty-Four

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons for Jane, on our thirty-fourth Accents of Remorse The good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect. First Sightings For all the attention paid to the “interview” scene in Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, its musical depths have proved remarkably resistant to analysis and have remained unplumbed. This striking passage of thirty-four whole-note chords has probably attracted more comment than any other in the opera since Andrew Porter first spotted shortly after the 1951 premiere that all the chords harmonize members of the F major triad, leading to much discussion over whether or not the passage is “in F major.” 1 Beyond Porter’s perception, the structure was far from obvious, perhaps in some way unprecedented, and has remained mysterious. Indeed, it is the undisputed gnomic power of its strangeness that attracted (and still attracts) most comment. Arnold Whittall has shown that no functional harmonic or contrapuntal explanation of the passage is satisfactory, and proceeded from there to make the interesting assertion that that was the point: The “creative indecision”2 that characterizes the music of the opera was meant to confront the listener with the same sort of difficulty as the layers of irony in Herman Melville’s “inside narrative,” on which the opera is based. To quote a single sentence of the original story that itself contains several layers of ironic ambiguity, a sentence thought by some—I believe mistakenly—to say that Vere felt no remorse: 1. -

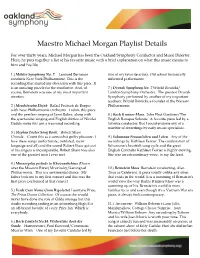

Michael Morgan Playlist

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

LOUISE ALDER | JOSEPH MIDDLETON Serge Rachmaninoff, Ativanovka, Hisfamily’S Country Estate,C

RACHMANINOFF TCHAIKOVSKY BRITTEN GRIEG SIBELIUS MEDTNER LOUISE ALDER | JOSEPH MIDDLETON Serge Rachmaninoff, at Ivanovka, his family’s country estate, c. 1915 estate,c. country hisfamily’s atIvanovka, Serge Rachmaninoff, AKG Images, London / Album / Fine Art Images Lines Written during a Sleepless Night – The Russian Connection Serge Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) Six Songs, Op. 38 (1916) 15:28 1 1 At night in my garden (Ночью в саду у меня). Lento 1:52 2 2 To Her (К ней). Andante – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Tempo precedente – Tempo I (Meno mosso) – Meno mosso 2:47 3 3 Daisies (Маргаритки). Lento – Poco più mosso 2:29 4 4 The Rat Catcher (Крысолов). Non allegro. Scherzando – Poco meno mosso – Tempo come prima – Più mosso – Tempo I 2:42 5 5 Dream (Сон). Lento – Meno mosso 3:23 6 6 A-oo (Ау). Andante – Tempo più vivo. Appassionato – Tempo precedente – Più vivo – Meno mosso 2:15 3 Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957) 7 Våren flyktar hastigt, Op. 13 No. 4 (1891) 1:35 (Spring flees hastily) from Sju sånger (Seven Songs) Vivace – Vivace – Più lento – Vivace – Più lento – Vivace 8 Säv, säv, susa, Op. 36 No. 4 (1900?) 2:32 (Reed, reed, whistle) from Sex sånger (Six Songs) Andantino – Poco con moto – Poco largamente – Molto tranquillo 9 Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte, Op. 37 No. 5 (1901) 2:59 (The girl came from meeting her lover) from Fem sånger (Five Songs) Moderato 10 Var det en dröm?, Op. 37 No. 4 (1902) 2:04 (Was it a dream?) from Fem sånger (Five Songs) Till Fru Ida Ekman Moderato 4 Edvard Grieg (1843 – 1907) Seks Sange, Op. -

5099943343256.Pdf

Benjamin Britten 1913 –1976 Winter Words Op.52 (Hardy ) 1 At Day-close in November 1.33 2 Midnight on the Great Western (or The Journeying Boy) 4.35 3 Wagtail and Baby (A Satire) 1.59 4 The Little Old Table 1.21 5 The Choirmaster’s Burial (or The Tenor Man’s Story) 3.59 6 Proud Songsters (Thrushes, Finches and Nightingales) 1.00 7 At the Railway Station, Upway (or The Convict and Boy with the Violin) 2.51 8 Before Life and After 3.15 Michelangelo Sonnets Op.22 9 Sonnet XVI: Si come nella penna e nell’inchiostro 1.49 10 Sonnet XXXI: A che piu debb’io mai l’intensa voglia 1.21 11 Sonnet XXX: Veggio co’ bei vostri occhi un dolce lume 3.18 12 Sonnet LV: Tu sa’ ch’io so, signior mie, che tu sai 1.40 13 Sonnet XXXVIII: Rendete a gli occhi miei, o fonte o fiume 1.58 14 Sonnet XXXII: S’un casto amor, s’una pieta superna 1.22 15 Sonnet XXIV: Spirto ben nato, in cui so specchia e vede 4.26 Six Hölderlin Fragments Op.61 16 Menschenbeifall 1.26 17 Die Heimat 2.02 18 Sokrates und Alcibiades 1.55 19 Die Jugend 1.51 20 Hälfte des Lebens 2.23 21 Die Linien des Lebens 2.56 2 Who are these Children? Op.84 (Soutar ) (Four English Songs) 22 No.3 Nightmare 2.52 23 No.6 Slaughter 1.43 24 No.9 Who are these Children? 2.12 25 No. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Berlioz's Les Nuits D'été

Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été - A survey of the discography by Ralph Moore The song cycle Les nuits d'été (Summer Nights) Op. 7 consists of settings by Hector Berlioz of six poems written by his friend Théophile Gautier. Strictly speaking, they do not really constitute a cycle, insofar as they are not linked by any narrative but only loosely connected by their disparate treatment of the themes of love and loss. There is, however, a neat symmetry in their arrangement: two cheerful, optimistic songs looking forward to the future, frame four sombre, introspective songs. Completed in 1841, they were originally for a mezzo-soprano or tenor soloist with a piano accompaniment but having orchestrated "Absence" in 1843 for his lover and future wife, Maria Recio, Berlioz then did the same for the other five in 1856, transposing the second and third songs to lower keys. When this version was published, Berlioz specified different voices for the various songs: mezzo-soprano or tenor for "Villanelle", contralto for "Le spectre de la rose", baritone (or, optionally, contralto or mezzo) for "Sur les lagunes", mezzo or tenor for "Absence", tenor for "Au cimetière", and mezzo or tenor for "L'île inconnue". However, after a long period of neglect, in their resurgence in modern times they have generally become the province of a single singer, usually a mezzo-soprano – although both mezzos and sopranos sometimes tinker with the keys to ensure that the tessitura of individual songs sits in the sweet spot of their voices, and transpositions of every song are now available so that it can be sung in any one of three - or, in the case of “Au cimetière”, four - key options; thus, there is no consistency of keys across the board. -

Federica Marsico a Queer Approach to the Classical Myth of Phaedra in Music

Federica Marsico A Queer Approach to the Classical Myth of Phaedra in Music Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ nr 34 (3), 7-28 2017 Federica Marsico UNIVERSITY OF PAVIA A Queer Approach to the Classical Myth of Phaedra in Music The Topic In the second half of the 20th century, the myth of Phaedra, according to which the wife of King Theseus of Athens desperately falls in love with her stepson Hippolytus, was set to music by three homosexual compos- ers in the following works: the dramatic cantata Phaedra for mezzo- soprano and small orchestra (1976) by Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) after a text by the American poet Robert Lowell, the opera Le Racine: pianobar pour Phèdre (1980) by Sylvano Bussotti (1931) after a libretto drafted by the Italian composer himself and consisting of a prologue, three acts, and an intermezzo, and, last but not least, the two-act con- cert opera Phaedra (2007) by Hans Werner Henze (1926-2012) after a libretto by the German poet Christian Lehnert.1 1 In the second half of the century, other musical adaptations of the myth were also composed, namely the one-act opera Phèdre by Marcel Mihalovici (1898–1986) after a text by Yvan Goll and consisting in a prologue and five scenes (1951), the chamber opera Syllabaire pour Phèdre by Maurice Ohana (1913–1992) after a text by Raphaël Cluzel (1968), and the monodrama Phaedra for mezzo-soprano and orchestra by George Rochberg (1918–2005) after a text by Gene Rosenfeld (1976). 7 Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ, nr 34 (3/2017) This paper summarizes the results of a three-year research project (2013–2015)2 that has proved that the three above-mentioned homo- sexual composers wilfully chose a myth consistent with an incestu- ous—and thus censored—form of love in order to portray homoerotic desire, which the coeval heteronormative society of course labelled as deviant and hence condemned. -

That to See How Britten Handles the Dramatic and Musical Materials In

BOOKS 131 that to see how Britten handles the dramatic and musical materials in the op- era is "to discover anew how from private pain the great artist can fashion some- thing that transcends his own individual experience and touches all humanity." Given the audience to which it is directed, the book succeeds superbly. Much of it is challenging and stimulating intellectually, while avoiding exces- sive weightiness, and at the same time, it is entertaining in the very best sense of the word. Its format being what it is, there are inevitable duplications of information, and I personally found the Garbutt and Garvie articles less com- pelling than the remainder of the book. The last two articles of Brett's, excel- lent as they are, also tend to be a little discursive, but these are minor reserva- tions. For anyone who cares for this masterwork of twentieth-century opera, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/4/3/131/1587210 by guest on 01 October 2021 or for Britten and his music, this book is obligatory reading. Carlisle Floyd Peter Grimes/Gloriana Benjamin Britten English National Opera/Royal Opera Guide 24 Nicholas John, series editor London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun Press, 1983 128 pages, $5.95 (paper) The English National Opera/Royal Opera Guides, small paperbacks with siz- able contents, are among the best introductions available to the thirty-plus operas published in the series so far. Each guide includes some essays by ac- knowledged authorities on various aspects of its subject, followed by a table of major musical themes, a complete libretto (original language plus transla- tion), a brief bibliography, and a discography.