James Taylor, Inside and Outside the London Stock Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defenses to Customer Claims Against Stockbrokers

DEFENSES TO CUSTOMER CLAIMS AGAINST STOCKBROKERS Elizabeth Hoop Fay, Esquire Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Philadelphia Foster S. Goldman, Jr., Esquire Markel Schafer & Goldman, PC Pittsburgh DEFENSES TO CUSTOMER CLAIMS AGAINST STOCKBROKERS I. DEFENSES TO CHURNING, SUITABILITY AND UNAUTHORIZED TRADING CLAIMS A. The Elements of Causes of Action for Churning, Unsuitable Recommendations and Unauthorized Trading 1. Churning of a brokerage account occurs when a broker who exercises control over the trading engages in an excessive number of transactions in order to generate commissions. See, e.g., Costello v. Oppenheimer & Co., Inc., 711 F.2d 1361, 1368-69 (7th Cir. 1983). To prevail on a churning claim, the customer must prove three elements: (1) control of the account by the broker; (2) trading activity that is excessive in light of the customer’s investment objectives; and (3) that the broker acted with scienter, i.e., intent to defraud or reckless disregard of the customer’s interests. Craighead v. E.F. Hutton & Co., 899 F.2d 485, 489 (6th Cir. 1990). 2. While a churning claim is a challenge to the quantity of transactions, a suitability claim challenges the quality of the investments recommended by the broker. To prevail on a suitability claim, the customer generally must prove: (1) that the broker recommended securities that are unsuitable in light of the customer’s investment objectives; and (2) that the broker did so with intent to defraud or with reckless disregard for the client’s interests. E.g., Brown v. E.F. Hutton Group Inc., 991 F.2d 1020, 1031 (2d Cir. 1991). 3. -

NSP Price List

Network Service Provider Price List For Network Service Providers providing customer access to London Stock Exchange Group Trading and Information Systems Price List Network Service Providers Effective 01 January 2021 London Stock Exchange plc. Registered in England & Wales No 02075721. Registered office 10 Paternoster Square, London EC4M 7LS. Network Service Provider Price List For Network Service Providers providing customer access to London Stock Exchange Group Trading and Information Systems Service Monthly cost per NSP per client per setup*/GBP London Stock Exchange Interactive Services1 1,995 London Stock Exchange Information Services 2,205 London Stock Exchange Testing Only Services2 645 London Stock Exchange Derivatives Market 260 Turquoise Interactive Services1 330 Turquoise Information Services 441 Borsa Italiana Equities 330 Borsa Italiana IDEM Derivatives 330 EuroTLX 330 Notes: 1Includes Trading, Drop-Copy and Post-Trade Gateways, and CDS. 2This service is included for free when ordered with London Stock Exchange Interactive Services or London Stock Exchange Information Services. If you are interested in taking FixHub services, please contact [email protected] for further information. Please note that all services are subject to a 90-day notice period for cancellation. All new services ordered are subject to a minimum 12-month service term. Orders *The ordering and cancellation of services is only supported by an NSP submitting a valid Technical Information Form to [email protected] For more information, please contact our Technology Business Development team on +44 (0)20 7797 3211 or email [email protected] London Stock Exchange plc. Registered in England & Wales No 02075721. Registered office 10 Paternoster Square, London EC4M 7LS. -

Ladies of the Ticker

By George Robb During the late 19th century, a growing number of women were finding employ- ment in banking and insurance, but not on Wall Street. Probably no area of Amer- ican finance offered fewer job opportuni- ties to women than stock broking. In her 1863 survey, The Employments of Women, Virginia Penny, who was usually eager to promote new fields of employment for women, noted with approval that there were no women stockbrokers in the United States. Penny argued that “women could not very well conduct the busi- ness without having to mix promiscuously with men on the street, and stop and talk to them in the most public places; and the delicacy of woman would forbid that.” The radical feminist Victoria Woodhull did not let delicacy stand in her way when she and her sister opened a brokerage house near Wall Street in 1870, but she paid a heavy price for her audacity. The scandals which eventually drove Wood- hull out of business and out of the country cast a long shadow over other women’s careers as brokers. Histories of Wall Street rarely mention women brokers at all. They might note Victoria Woodhull’s distinction as the nation’s first female stockbroker, but they don’t discuss the subject again until they reach the 1960s. This neglect is unfortu- nate, as it has left generations of pioneering Wall Street women hidden from history. These extraordinary women struggled to establish themselves professionally and to overcome chauvinistic prejudice that a career in finance was unfeminine. Ladies When Mrs. M.E. -

London Stock Exchange Group Response to CCP Resolution Guidance Consultation 2017

London Stock Exchange Group Response to the Financial Stability Board Consultative Document on “Guidance on Central Counterparty Resolution and Resolution Planning” Introduction LSEG operates today multiple clearing houses. It has majority ownership of the multi-asset global CCP operator, LCH Group (“LCH”). LCH has legal subsidiaries in the UK (LCH Ltd), France (LCH S.A.), and the US (LCH LLC). It is a leading multi-asset class and international clearing house, serving major international exchanges and platforms as well as a range of OTC markets. It clears a broad range of asset classes, including: securities, exchange-traded derivatives, commodities, energy, freight, foreign exchange derivatives, interest rate swaps, credit default swaps and euro, sterling and US dollar denominated bonds and repos. In addition, LSEG operates Cassa di Compensazione e Garanzia S.p.A. ("CC&G"), the Italian clearing house, providing clearing services for a range of European securities as well as exchange traded equity and commodities derivatives. The Group also includes Monte Titoli, a CSD successfully migrated in Target 2 – Securities settlement platform; and globeSettle, the Group’s CSD based in Luxembourg. In this context, LSEG welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Financial Stability Board (“FSB”) Consultative Document on “Guidance on Central Counterparty Resolution and Resolution Planning”. *** 1 Part A. General Remarks While defining the recovery and resolution framework for CCPs, two key objectives should be pursued: (i) preserve the incentives for clearing members to maintain high CCP resilience standards and to actively participate in recovery and (ii) ensure that the recovery and resolution processes are transparent and predictable on order to maximise the chance of success. -

The Operations of a Typical Stockbroker and an Issuing House

THE OPERATIONS OF A TYPICAL STOCKBROKER AND AN ISSUING HOUSE A PAPER PRESENTED BY MR. AZU ODITA GENERAL MANAGER/CEO, NETWORTH SECURITIES & FINANCE LIMITED (A MEMBER OF THE NIGERIAN STOCK EXCHANGE) LAGOS, NIGERIA Outline Who is a Stockbroker Requirements of a Stockbroker Services offered by a Stockbroker Relationship with other Stakeholders in the capital market Who is a Stockbroker A licensed dealing member of an Exchange Ø To deal in financial instruments available in the Money & Capital Markets uPrimary activity is in the capital market Dealing firms are the principal while the Authorized dealing clerks are the brokers/agents of the dealing firms Other features Ø Registered with CAC and SEC Ø Roles in the market depend on Capital bases, Expertise and Status of Registration u Broker = N40 Million u Dealer = N30 Million u Broker/Dealer = N70 Million – A broker transacts on behalf of customers only while a dealer transacts on behalf of his company Requirements of a Stockbroker ØIntegrity – His Word is his Bond ØInnovation in value-added services e.g. Margin Trading, Security Lending, REPO transactions ØKnow your Client (KYC) ØExcellent Analytical Skill ØFinancial Training ØFund Management & Administration ØFinancial Supermarket - gain advantage of size & distribution network ØOffshore Alliance. Services Offered by A Stockbroking Firm Not standardised Ø Differs from one organisation to another Examples Stockbroking New Issues Research & Portfolio Management Bond Trading Credit Analysis Stockbroking Receives and process transaction orders -

Semi Annual Report April 2008

FEDERATION OF EURO-ASIAN STOCK EXCHANGES SEMI ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2008 FEDERATION OF EURO-ASIAN STOCK EXCHANGES SEMI ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Federation of Euro-Asian Stock Exchanges 3 Deutsche Boerse 10 Garanti Asset Management 13 Is Investment 14 NASDAQ OMX 16 Tayburn Kurumsal 18 Finans Asset Management 20 Quartal FLife 21 Stock Exchange Profiles Abu Dhabi Securities Market 24 Amman Stock Exchange 28 Armenian Stock Exchange 32 Bahrain Stock Exchange 36 Baku Interbank Currency Exchange 40 Baku Stock Exchange 44 Banja Luka Stock Exchange 46 Belarusian Currency and Stock Exchange 50 Belgrade Stock Exchange 54 Bucharest Stock Exchange 58 Bulgarian Stock Exchange 62 Cairo and Alexandria Stock Exchanges 66 Georgian Stock Exchange 70 Iraq Stock Exchange 74 Istanbul Stock Exchange 78 Karachi Stock Exchange 82 Kazakhstan Stock Exchange 86 Kyrgyz Stock Exchange 90 Lahore Stock Exchange 94 Macedonian Stock Exchange 96 Moldovan Stock Exchange 100 Mongolian Stock Exchange 104 Montenegro Stock Exchange 108 Muscat Securities Market 112 Palestine Securities Exchange 116 Sarajevo Stock Exchange 120 State Commodity & Raw Materials Exchange of Turkmenistan 122 Tehran Stock Exchange 126 Tirana Stock Exchange 130 “Toshkent” Republican Stock Exchange 134 Ukrainian Stock Exchange 138 Zagreb Stock Exchange 142 Affiliate Member Profiles CDA Central Depository of Armenia 147 Central Registry Agency Inc. of Turkey 148 Central Securities Depository of Iran 149 Macedonian Central Securities Depository 150 Misr For Clearing, Settlement & Central Depository 151 Securities Depository Center (SDC) of Jordan 152 Takasbank - ISE Settlement and Custody Bank, Inc. 153 Tehran Securities Exchange Technology Management Company (TSETMC) 154 Member List 155 FEDERATION OF EURO-ASIAN STOCK EXCHANGES (FEAS) The Federation of Euro-Asian Stock Exchanges Semi Annual Report April 2008 is published by the Federation of Euro-Asian Stock I.M.K.B Building, Emirgan 34467 Istanbul, Turkey Exchanges. -

The Professional Obligations of Securities Brokers Under Federal Law: an Antidote for Bubbles?

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2002 The rP ofessional Obligations of Securities Brokers Under Federal Law: An Antidote for Bubbles? Steven A. Ramirez Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Ramirez, Steven, The rP ofessional Obligations of Securities Brokers Under Federal Law: An Antidote for Bubbles? 70 U. Cin. L. Rev. 527 (2002) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROFESSIONAL OBLIGATIONS OF SECURITIES BROKERS UNDER FEDERAL LAW: AN ANTIDOTE FOR BUBBLES? Steven A. Ramirez* I. INTRODUCTION In the wake of the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed legislation specifically designed to extend greater protection to the investing public and to elevate business practices within the securities brokerage industry.' This legislative initiative ultimately gave birth to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the '34 Act).' The '34 Act represented the first large scale regulation of the nation's public securities markets. Up until that time, the securities brokerage industry4 had been left to regulate itself (through various private stock exchanges). This system of * Professor of Law, Washburn University School of Law. Professor William Rich caused me to write this Article by arranging a Faculty Scholarship Forum at Washburn University in the'Spring of 2001 and asking me to participate. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

Your Financial Events. Anytime. Anywhere

Your financial events. Anytime. Anywhere. Issuer Services lsegissuerservices.com Live corporate presentations, events and meetings Spark Live offers a unique opportunity to place your content on a trusted website with millions of visitors, so you can maximise the reach of every event in your corporate calendar. With Spark Live, you can offer live and on demand access to your financial results, capital markets days, analyst updates, AGMs and all the important moments in your corporate calendar. Our unique platform lets you integrate your broadcasts into your fully branded London Stock Exchange profile page and open your events to our network of millions. Embed your broadcasts simultaneously into your existing Investor Relations channels to maximise your reach. – Reach millions of investors: through your profile on our trusted portal, your broadcasts are made available to millions of visitors at londonstockexchange.com – Tell your story: enhance your profile page with branding, social media feeds, research and event calendars to support your corporate marketing strategy. – Maximise your content views: investors can view your events in real time or catch up on demand. Wherever and whenever works for them. – Build powerful communications: use our tools to add investor Q&As, slide synching, speaker bios, presentation downloads, transcripts and more. – Broadcast worldwide: broadcast your financial results, capital markets days or analyst updates from any location to increase the reach of every event. Drive visibility, liquidity and demand through -

Scrip Dividend in the Form of New Shares

Your responsibilities Principal register Hong Kong Overseas Branch register THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are Computershare Investor Services PLC Computershare Hong Kong Investor Services Limited in any doubt about this document or as to the action you should take, you should consult a Whether or not it is to your advantage to elect to receive new shares in lieu of a cash The Pavilions Rooms 1712-1716, 17th Floor stockbroker, solicitor, accountant or other appropriate independent professional adviser. dividend or to elect to receive payment in US dollars, sterling or Hong Kong dollars Bridgwater Road Hopewell Centre If you sold or transferred all or some of your ordinary shares on or before 15 May 2019, but those is a matter for individual decision by each shareholder. HSBC cannot accept any Bristol 183 Queen’s Road East shares are included in the number shown in box 1 on your form of election or entitlement advice for responsibility for your decision. BS99 6ZZ Hong Kong SAR the first interim dividend for 2019, you should, without delay, consult the stockbroker or other agent United Kingdom Telephone: +852 2862 8555 through whom the sale or transfer was effected for advice on the action you should take. Overseas shareholders Telephone: +44 (0) 370 702 0137 Email: [email protected] Email via website: Investor Centre: Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this document, make no representation as to its accuracy or No person receiving a copy of this document or the form of election in any jurisdiction www.investorcentre.co.uk/contactus www.investorcentre.com/hk Investor Centre: completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this document. -

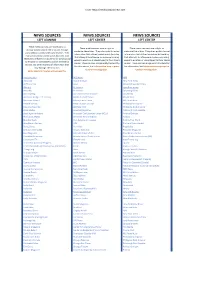

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

A Guide to Selecting a Stockbroker Or Investment Adviser

Assessing Your Needs Before you seek the services of a professional stockbroker or investment adviser, take some ti me to evaluate your Selecting needs and expectati ons. This analysis will help you choose the right person a Stockbroker for the job. or • Defi ne Your Goals Securiti es Division Short- and long-term goals need to be The Securities Division of the Secretary of Investment identified. Determine the degree of risk State’s Office is responsible for regulating you are willing to assume to achieve the offer and sale of certain types of Adviser your fi nancial goals. investments known as securities. These may include many types of stocks, bonds, limited partnerships, viatical sett lement investment • Determine Your Net Worth contracts, some oil and gas investments, Figure out your assets and liabiliti es -- and other investment contracts. what you own and what you owe. Be sure Our major activities include registration to take into account any growing debts, of securities offerings, the licensing of likely tax increases, or personal or health stockbrokers and investment advisers, and crises which may strain fi nances. the investigati on of alleged violati ons of the securiti es laws. • Anticipate Life Changes Please call us with any questi ons at Consider any plans which might have an 601-359-1334. Mississippi residents may impact on your fi nances, such as making a also reach us by calling toll-free at career change, having children, paying school 888-236-6167. tuiti on or reti ring. Securities Division P.O. Box 136 Jackson, MS 39205 601-359-1334 www.sos.ms.gov Dear Fellow Mississippians: Selecting Your Adviser To select the best Be sure to look for certain characteristics and qualifications when choosing someone to manage financial adviser, you your investments.